Editor’s note: This blog was updated 13 June 2023 to focus around building a differentiation strategy. New information about the types of differentiation strategies was added and irrelevant sections were removed.

Organizations follow a wide range of product strategies. Some companies aim to lead in innovation, some are fast-followers, and others are cost leaders. They back these strategies with their core competencies to differentiate their products in the market.

The type of market and maturity of the offering determine the kind of differentiation required to be successful in the market. An organization needs to understand the differentiation it can profitably offer based on the resources available (including human, capital, and partnerships).

In this guide, we’ll learn what a differentiation strategy is and why it’s vital for modern products. We’ll discuss the different types of differentiation strategies, what they look like, and how to build an effective differentiation strategy.

Throughout the article, we’ll refer to real-world examples and help demonstrate what a differentiation strategy looks like in practice and how a strong differentiation strategy can set you apart from your competitors.

A differentiation strategy is an effort to put your product (or service) in a unique market position that gives you an edge over competitors. Building a product that mimics another in every tangible way seldom creates a ripple — this type of product tends to be uncompetitive against others in the market and eventually fails. As such, in a world where consumers have ample choices to pick from, having a differentiation strategy is vital to set your product apart and cut through the noise.

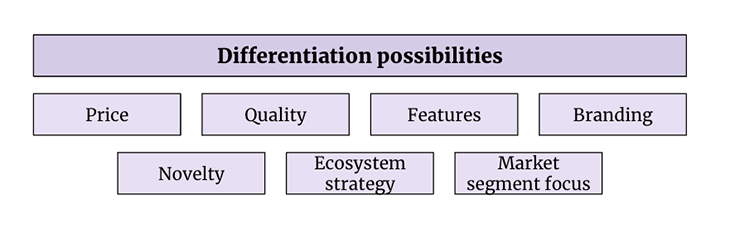

Today, differentiation strategies usually revolve around quality, features, and price. However, there are several other ways in which a product can stand out. For example, your differentiation strategy might be based on finding a different audience to buy your product, making another channel irrelevant. A partner/ecosystem strategy that accelerates access to the product, such as placing your product in prime locations within a store, is another potential differentiation strategy.

Other approaches to product differentiation include creating awareness of the product with effective marketing, having superior quality that other competitors can’t match (for example, Apple in the smartphone and computer market), or offering customizations that can’t be found in other products.

Product differentiation doesn’t have to be additive; it can be subtractive too. For example, I recently explored watches for kids and found the lack of features to be attractive: no games, no social media, no distractions. I quickly eliminated a suite of products that provided such capabilities.

When done right, differentiation can help drive better profit margins, customer lifetime value (CLV), and return on assets.

There are several ways to create product differentiation. That said, differentiation is driven by a market need (latent or active) in all cases.

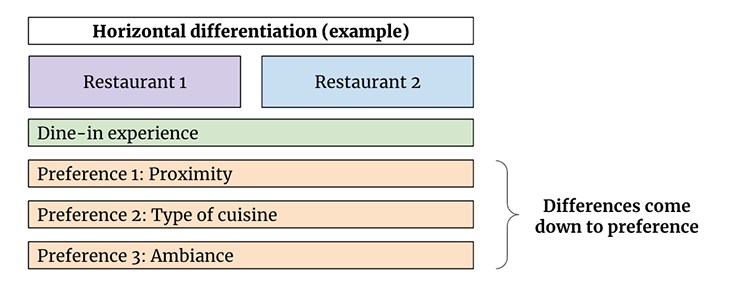

Differences in products that cannot necessarily be ranked as better or worse, but rather appeal to different customer preferences, are horizontal differentiation — the products are in the same market but have different options that aren’t directly comparable and seek to assuage a personal need.

One classic consumer example of this is car shopping. Consider two luxury sports car brands: Ferrari and Lamborghini. Both of these car brands offer high-performance vehicles that target a similar audience — individuals who appreciate luxury and status. Yet, these two brands distinctly differentiate themselves. A Ferrari is often seen as the epitome of Italian elegance and sophistication, focusing on smooth driving and racing heritage. Lamborghini, on the other hand, leans into its image of aggressive design and raw power. Both are premium, high-quality vehicles, but they appeal to slightly different consumer preferences.

Horizontal differentiation isn’t limited to tangible products, it’s present in everyday decisions too, such as choosing a restaurant. Although all restaurants serve meals, they differentiate themselves based on unique factors like cuisine, ambiance, or location, and the one you choose depends on your individual preferences. This choice is driven by your personal or group’s taste and other factors — a practical illustration of horizontal differentiation:

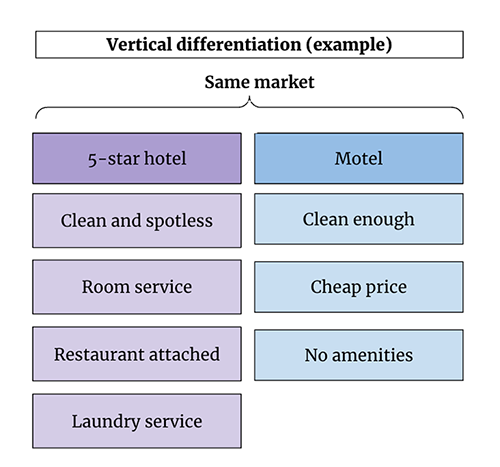

The placement often is also a function of the market segment. Vertical differentiation refers to differences in quality or amount that can be clearly ranked or graded. What you see in Walmart is generally different from what you’d find in Whole Foods, for example, even though they’re in the same product market.

Let’s use a specific example from the hospitality industry. Budget hotel chains like Motel 6 or Super 8 appeal to customers looking for a place to sleep at an affordable price. Nothing fancy is expected at these chains and the offerings are usually bare bones. In contrast, luxury hotel chains like The Ritz-Carlton or Four Seasons offer premium services, like room service, spas, on-site restaurants, etc. which inherently distinguish them from budget hotels. In this case, the vertical differentiation is based on the quality of service and amenities provided:

In many scenarios, you’ll see a blend of vertical and horizontal differentiation. Think of a Toyota Camry and the various trims as vertical differentiation. Trims typically range from a basic model to higher-end versions with additional features, better performance, or more comfortable seats. These can be ranked or graded based on their quality or level of sophistication. On the other hand, horizontal differentiation with the Camry can be seen in the variety of colors available. Choosing a red Camry over a blue one doesn’t necessarily mean one is better or of higher quality than the other, it’s just personal preference.

Here’s another example: breakfast bars have existed in the market for some time. However, when RXBar introduced its protein bars, it was presented as a higher quality option compared to other bars on the market and clearly listed its natural ingredients on the packaging. This created vertical differentiation. It’s also showcased in RXBar’s appeal to different consumer preferences. While primarily aimed at active individuals, RXBar’s real ingredients make it a viable choice for those seeking a nutritious breakfast bar, offering another option in the breakfast food category. This is horizontal differentiation.

In the early stages of development, assessing the market need and the differentiation required can be tricky. Take autonomous cars, for example — it’s still a fairly new market, and consumer needs and required differentiation factors aren’t fully clear yet. A mature product, such as smartphones, on the other hand, will leave few differentiation options and make it hard for products to stand out.

There are several options by which a product can stand out in the market, including:

Identifying the best levers requires considerable analysis and can be highly speculative in the absence of data. This makes companies risk-averse and forces them to take a red-ocean strategy even when there is a clear path to a blue-ocean approach.

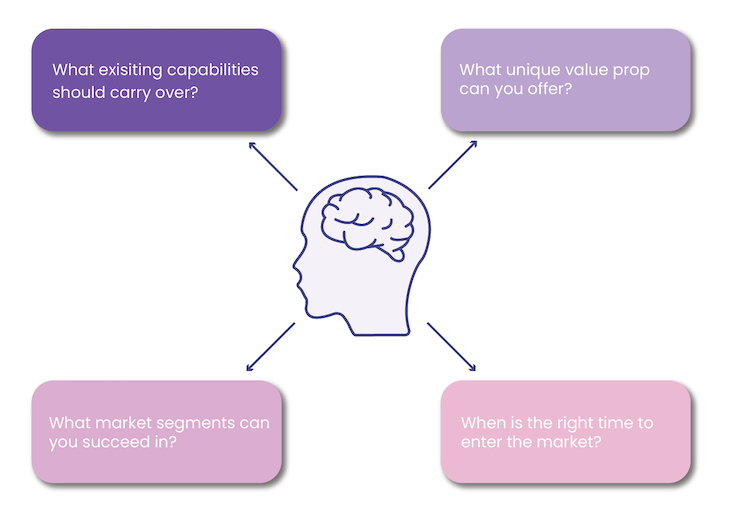

The questions I often hear from other product managers are:

As a product manager, it’s your job to assess the ability of a new product against the market to determine whether it can offer sufficient differentiation that is profitable for the organization. You can accomplish this by identifying current market offerings, trends, product maturity in the market segment, and the gaps thereof.

With these insights, you can lead your teams to build an exciting new offer, time its entry into the market just right, and differentiate it sufficiently across multiple parameters. Once deployed, measure and monitor the product to review your strategies and augment them, including considerations for end-of-life offerings.

A good product differentiation strategy doesn’t appear overnight — it often requires meticulous planning and lots of research. To build an effective product differentiation strategy, it’s necessary to:

When assessing the potential for a new product or solution, it’s helpful to take stock of important aspects of the current market and environment. I typically find the 5 Cs of situational analysis to aid in this discovery.

The 5 Cs are:

The context and consumer angle should inform of the market maturity, technological capabilities, captured pain points, and problems that remain to be solved. I often use Porter’s Five Forces model to identify (at an industry level) the supply and demand for such solutions, the product’s ability to be substituted, or the threshold for new entrants.

For example, Red Bull could be perceived as a substitute for coffee. Platforms such as Salesforce and Android continue to reduce entry barriers for startups. And so on…

We’ll get to collaborators in the next section, but no discovery is complete without competitive analysis. This is often the principal mistake startups make: assuming their work is pure greenfield. It’s crucial to consider the market needs against the offerings to define your MVP and determine how to stand out from the crowd.

Another essential part of this discovery process is to consider existing pain points that remain uncovered. These can often be minor with high upside potential and require domain expertise and a close watch of the business process (in B2B environments).

The best way to play this out is with your UX team to engage and shadow current processes using tools such as the five whys.

Eventually, this information gathering should answer the following:

As an example, consider salvage vehicles. When salvors buy a vehicle, they often request a car history through Carfax. Unlike when purchasing a regular vehicle, the report isn’t as helpful. However, most salvors buy them for their records, and there aren’t additional details others can offer. What we have is a saturated market with a monopoly.

Imagine that data exists exclusively with your organization to build a better report. It certainly is an unmet (and latent) need. If we decided to pursue the same audience through the same channel (e.g., build a CarFax-like website), it would take years to displace Carfax because its audience is enormous.

The brand awareness and adoption of Carfax will position everything against you even though you have a superior product (at least on paper) and a lower price. We’ll follow this narrative to see if it’s worth pursuing in the next section.

Getting to the specifics of what you can offer and where should be grounded on the following questions:

Following along with the Carfax example from the previous section, an alternative approach would be to go where the market access is.

The salvage vehicles are sold by insurance companies. Without getting into details, the theory of The Market for Lemons explains why a certified used vehicle gets higher bidding than a private party vehicle. The same economics of adverse selection can also explain why it is a win-win for insurance carriers.

Let’s say displaying such a report increases the value of a vehicle by $200, on average. We could sell such a report for $15–20 when a Carfax report sells for $5. When insurance carriers display this information, it eradicates the need for a CarFax report.

Since the top 10 insurance carriers account for about 75 percent of the market, scale is not an issue. A simple shift in the audience can get you significant market penetration at a much higher price point.

When differentiating a product, think beyond the direct competition. You’d be right to believe that this would obliterate the competitor, but not head-to-head.

It takes a village to build and deliver a product. Getting buy-in from stakeholders is critical.

When you consider building a differentiated product, that implies, as we mentioned before, viability, feasibility, and usability. Product differentiation often starts with the UX and the engineering teams assessing the cost of building the differentiation.

This, in turn, determines the product’s viability or pricing. It is possible, with good marketing, to improve the price point; when there is awareness, it drives a premium. Similarly, packaging good service — e.g., a warranty package or a customer success team — is another good strategy to ensure adoption.

This also implies your organization needs this capability. Don’t promise a differentiation you cannot deliver.

A concept that often falls by the wayside is communicability. Can you express the advantages of your differentiation in simple weekend language? If your sales and marketing teams don’t present an impactful statement on the value prop, it won’t matter how good your product is.

The process by which film producers in India monitor audience engagement and experiment accordingly to convert on-stage dramas into successful movies can inform our discussion about product differentiation. Over the course of 5–10 iterations, scripts originally written for the stage are tightened and refined for the big screen.

Imagine you had a way to do the same with your product. The key questions would be:

I’m sure you’ve seen your share of products that Google introduces and shuts down. It would be simplistic to believe that these decisions are made frivolously, but every move Google makes regarding its products is based on data.

It is important to remember that maintaining a product requires continuous capital investment. Of course, capital is not an infinite resource. When one product holds it up, it deprives another, potentially one that can drive better revenues and profitability.

For this reason, it is crucial to measure and monitor product data to determine how every differentiation contributes to both positive and negative traction. Categories of metrics to monitor for product success include:

To wrap up, having a solid differentiation strategy is vital for a product’s success in today’s world of choices. Not only does a differentiation strategy help amplify customer engagement, it also improves profitability.

Featured image source: IconScout

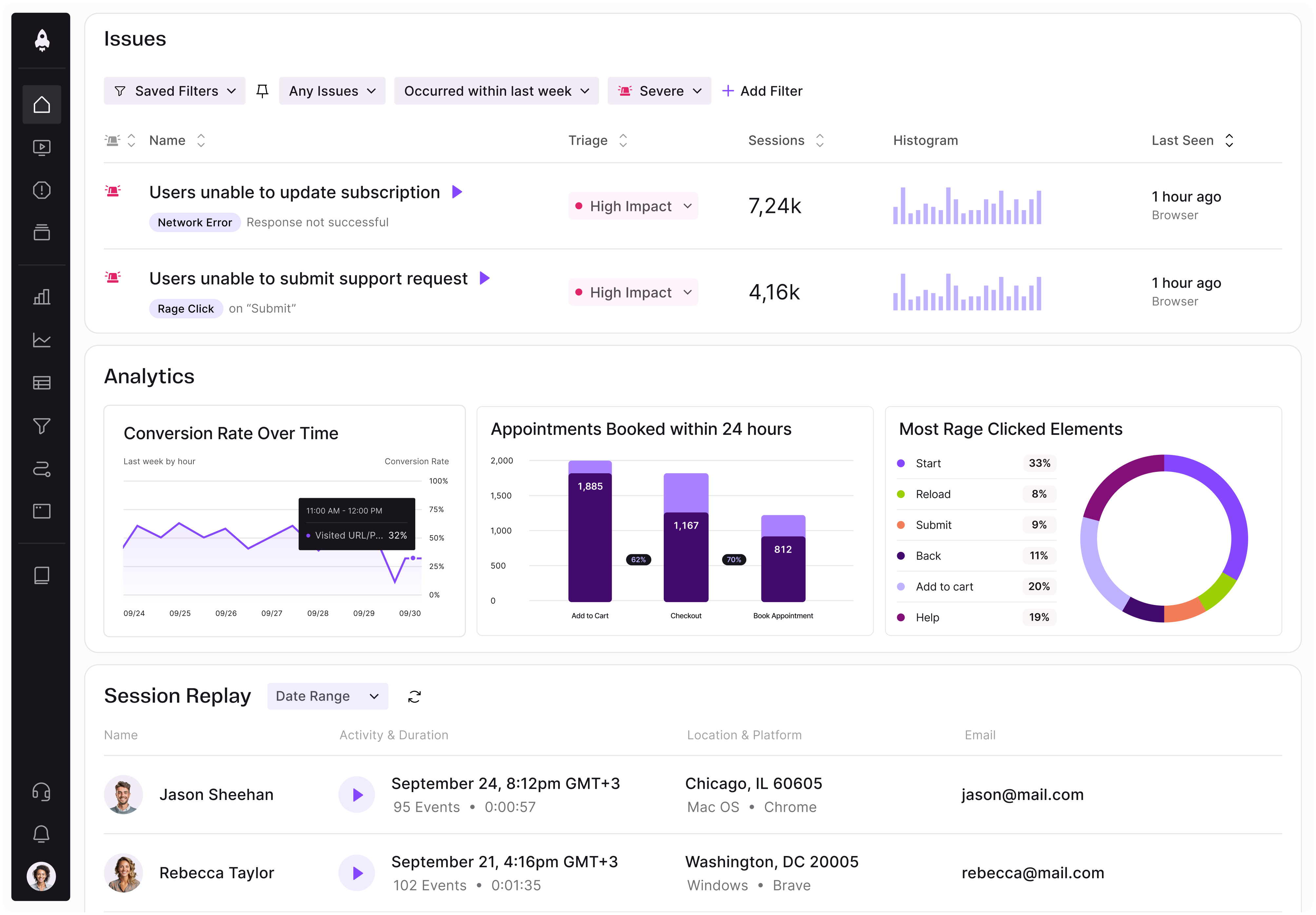

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

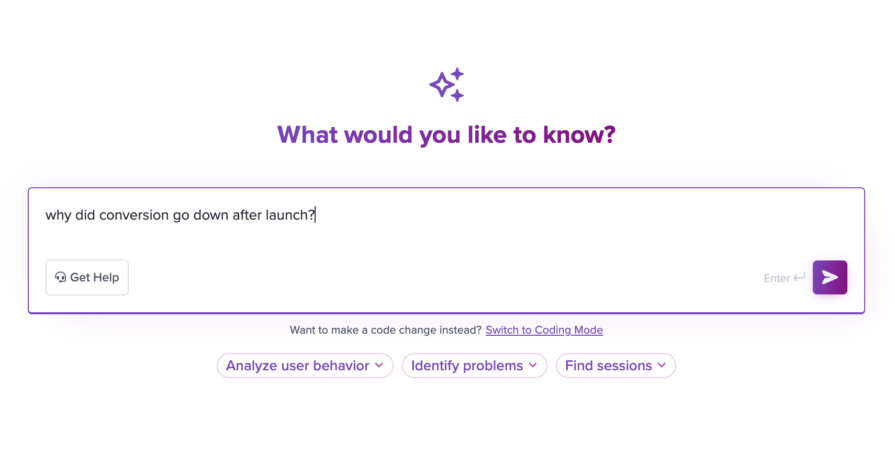

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.