In this guide, we’ll define the term minimum viable product (MVP) in the context of product management, list some advantages of adopting this approach, and walk you through the steps involved in actually researching and creating a minimum viable product.

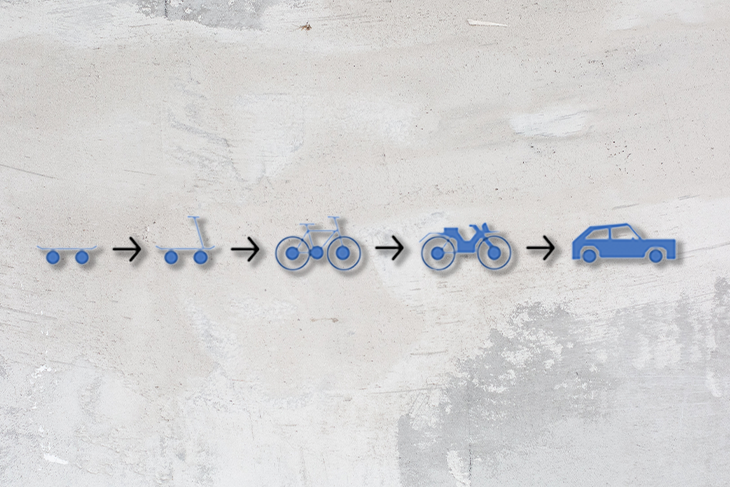

Minimum viable product refers to the minimum set of core features in an app or product that solves the user’s need and thus delivers value. An MVP is an early version of a product built from scratch with bare-bones features and basic functionality that aims to appeal to early adopters.

In 2001, Frank Robinson, cofounder and president of Syncdev, came up with the concept of minimum viable product and defined it as a unique product that maximizes return on the risk for both customer and supplier.

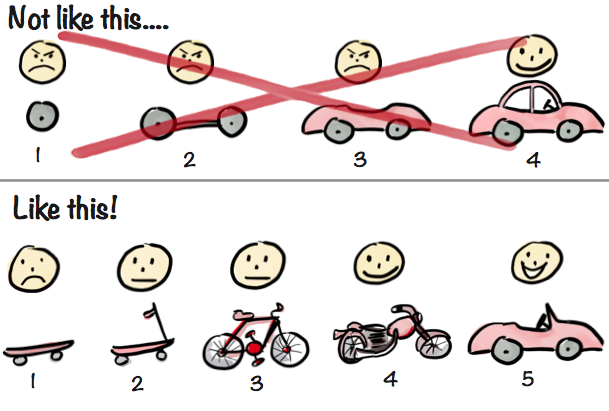

To explain this further, let’s say we have a product that was built from scratch with many features that consumed a lot of time, effort, and money. When it was launched to the market, users didn’t like the idea and the product was a failure.

In this example scenario, the product team wasted all its resources to create something big that was not even needed in the market. The principle of MVP states that product teams should instead aim to build something useful with minimal features and effort.

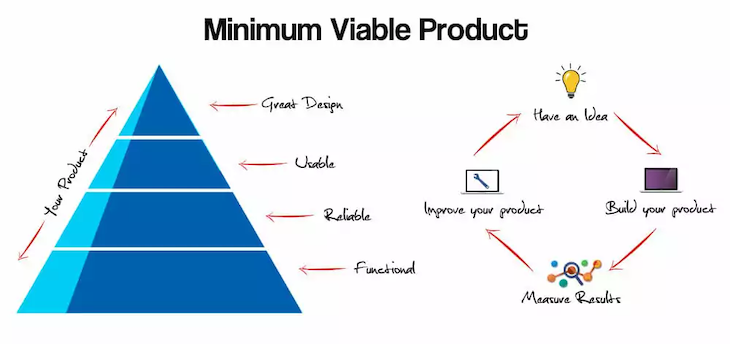

A minimum viable product, when launched into the market, can help CEOs and product managers gauge the appeal of the product among its user base. An MVP provides a specific value to users, which then makes it saleable and helps CEOs test their assumptions of the product’s usability and demand in the market.

The definition of minimum viable product, according to Frank Robinson, is as follows:

“The MVP is the right-sized product for your company and your customer. It is big enough to cause adoption, satisfaction, and sales, but not so big as to be bloated and risky. Technically, it is the product with maximum ROI divided by risk. The MVP is determined by revenue-weighting major features across your most relevant customers, not aggregating all requests for all features from all customers.”

Later on, Eric Ries, an entrepreneur, blogger and author of the book The Lean Startup, popularized this concept. Ries, describes a minimum viable product thusly:

“The minimum viable product is that version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort.”

The MVP approach to product development and management can help the team build better-performing products gradually using customer feedback.

Let us take a look at some specific ways in which adopting the minimum viable product approach can benefit product managers or CEOs.

CEOs and product managers generally come in with assumptions about the target segment and the market need based on data they’ve gathered. After an MVP is launched, these hypotheses about the target segment and market need can actually be validated. Product managers can get invaluable insight from customer feedback and usage metrics to help them determine next steps for the product strategy.

A minimum viable product, as you might imagine, typically contains minimum features. That’s because building these features requires fewer resources and less time compared to the resources required to build a product with a large number of features. This enables product managers to introduce the product to market much earlier and test whether the core features are actually meeting the market need.

An MVP consists of basic features that can provide value to the user. This approach enables developers to hyper-focus on only these minimal, key features, which leads to higher-quality results and a better user experience.

An MVP is the most basic version of a product and allows the team to validate the user flow and adoption of core features. By analyzing the user journey, product managers and designers can determine whether the features are being used as expected and, if necessary, establish a scope for improvement to make the user experience smoother. Any feedback or analyzed data is helpful to iterate the MVP with a better version.

Most people who found or build a product require investment from VCs at a certain stage. If there is already an MVP on the market that has users — and, moreover, if users are paying for those core features — it is considerably easier to impress investment firms and onboard them.

Since the effort involved is minimal and focused only on core features, the risk involved in launching an MVP is fairly low. If you launch a full-fledged product with a large suite of features after spending a considerable sum of money and resources, it will be an abject failure if you determine later on that the market need does not exist. By focusing on core features, product development teams can fail and learn from that failure more quickly, thereby reducing the risk.

Highlighting the core features and the value it can deliver can help you build relationships with early adopters. If these users find value in your product, they’re more likely to proactively share their feedback to help you improve the product further. They’re also more likely to spread the word about the product among their circle.

There are two main types of minimum viable product:

The table below further illustrates the difference between a low- and high-fidelity MVP:

| Low-fidelity MVP | High-fidelity MVP | |

| Goal | Explore the customer’s problem and the expected solution | Determine the solution’s value and customers’ willingness to pay for it |

| Objectives |

|

|

| Effort | Minimal; can be done in a short time period with very few resources | Time-consuming and effort-intensive; involves a small team of developers, designers and QA |

| Complexity | Simple; may not need development | Fairly complex; needs development |

| Example |

|

|

Now that we understand what a minimum viable product is, the benefits of the approach for product managers and CEOs, and the two main types of MVP, let’s take a deeper dive and demonstrate how to actually create one.

Below is a step-by-step breakdown of how to define and build a minimum viable product.

The first step is to do in-depth research to define the problem the MVP will be designed to solve. At this stage, product managers should ask questions such as:

The goal of this market research is to gather enough data to support the solution to be offered. Qualitative data is helpful as well to validate the existing gap in the market. Startups often fail because they do not spend enough time on market research before starting to build an idea.

Before you get into what needs to be built, it is crucial to understand your company’s goals. You must have a clear understanding of why your company exists in the first place.

Your company’s mission statement should answer that question, and the MVP you plan to build and the value it offers must concur with this mission. If, as a startup, you are launching an MVP as your first product, it can be helpful to write down the organization’s mission statement to provide a clear direction toward what needs to be done.

Define the goals you tend to achieve by launching MVP. Are you working towards achieving a certain amount of revenue in the next one year? Are you focused on only increasing user engagement? These goals will help in defining what features need to be built.

Once you have set objectives, it’s time to define the user journeys, target segments, user personas, and their actions and then work toward identifying their pain points.

This brainstorming activity can help you and your team identify what solutions can resolve those pain points and understand the benefits of each solution. Evaluate the list of solutions based on your objectives and then define the core features that you will be working on.

Meanwhile, it’s important to keep in mind that the features that make the MVP must be viable and the company must be able to sell the product after launch.

Let’s take a look at some well-known examples of products that started as minimum viable products (MVPs) in the technology world and then expanded into fully scaled products.

Drew Houston, CEO of Dropbox, initially had a tough time raising an investment fund. It was difficult to demonstrate the product and its need in the market without a working application until Houston came up with the idea of creating an MVP in the form of a video.

This three-minute video demonstrated the basic functions of the application. After the launch of the video, according to Houston, the beta waiting list went up from 5,000 to 75,000 overnight. This validated the market need and convinced Houston (and, crucially, investors) that the valuable resources required to bring this product to market would be worth it.

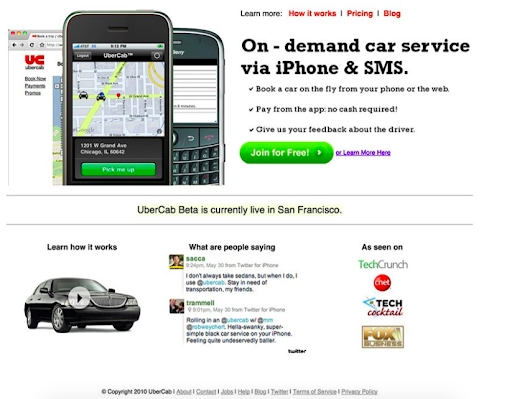

In 2008, Garrett Kamp and Travis Kalanick had an idea to pair drivers who are willing to take passengers with people who wanted a ride. Instead of creating an app with complicated features and an algorithm that matches a driver with a passenger, they launched UberCab, a very simplified version of today’s Uber.

The booking was done via SMS, but payment was handled via the app. Initially, it was only available in San Francisco before scaling gradually as other features were developed.

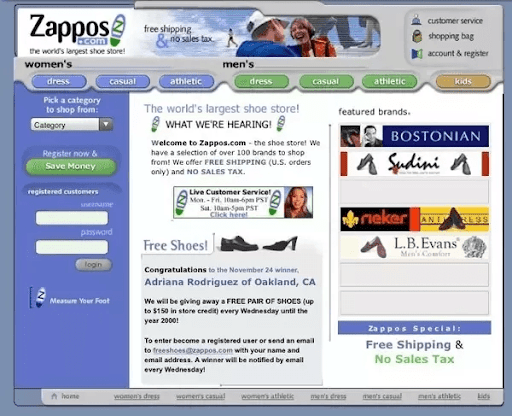

In 1999, Nick Swinmurn had an idea to sell shoes online. To test his idea, he created a simple website, shoesite.com, and started publishing images of shoes he wanted to sell.

Swinmum did not have any inventory and did not invest into the supply chain and logistics. Whenever a customer placed an order, he would buy the item from a local store and ship it to the customer. This helped him to validate his idea without any risk or investment.

Later, shoesite.com was developed into Zappos and ultimately acquired by Amazon.

It’s always a good idea to start with an MVP. This approach enables product leaders to gather customer feedback and eventually iterate it to add new features as the user base grows. Not only does it reduce risk, but it also enables developers to build products focused on customers needs. Building a minimum viable product enables you to test the business hypothesis before launching a full-fledged product, which, in turn, boosts the organization’s confidence to invest more.

Many well-known organizations have started with an MVP and, after a considerable number of iterations, created a billion-dollar business. These success stories validate the MVP approach of launching a minimum viable product before gradually moving toward a robust, well-tested, and proven development strategy.

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

The continuous improvement process (CIP) provides a structured approach to delivering incremental product enhancements.

As a PM, you’re responsible for functional requirements and it’s vital that you don’t confuse them with other requirements.

Melani Cummings, VP of Product and UX at Fabletics, talks about the nuances of omnichannel strategy in a membership-based company.

Monitoring customer experience KPIs helps companies understand customer satisfaction, loyalty, and the overall experience.