Have you ever worked in an organization where a strategy exists, but you don’t feel like you can effectively execute on it, as every team has different priorities? Or worked in a team that doesn’t feel like it can do anything to contribute towards the strategy?

Far too often, product leaders are scared to shift their teams to really focus on the strategy and common goals. Instead, we organize our teams around functions such as particular products, or particular elements within a product.

There is some value in this, but it doesn’t always mean that you’ll be working on the most valuable opportunity in the organization. Sometimes, you’ll just be filling time.

So what’s the answer? You need to craft an amazing strategy and align your teams around this to achieve this effectively. Is this easy? Not necessarily. Does it have a huge impact on the value your product teams can deliver? Absolutely.

Product strategy is the bridge between vision and execution. It clearly states the key bets you’re making. Product strategy highlights where you want to focus and your rough plan of attack.

If you already are sold on product strategy, know how to create one, and now want to understand how to maximize the value of your product strategy, keep reading.

Organizations tend to face less difficulty creating the strategy than actually executing on it. 61 percent of respondents acknowledge that their firms often struggle to bridge the gap between strategy formulation and its day-to-day implementation.

One of the main reasons why teams struggle to bridge the gap is that the strategy doesn’t become the main piece of the puzzle for the organization. It exists, but teams continue to work on their own agendas and the strategy doesn’t really influence what they do.

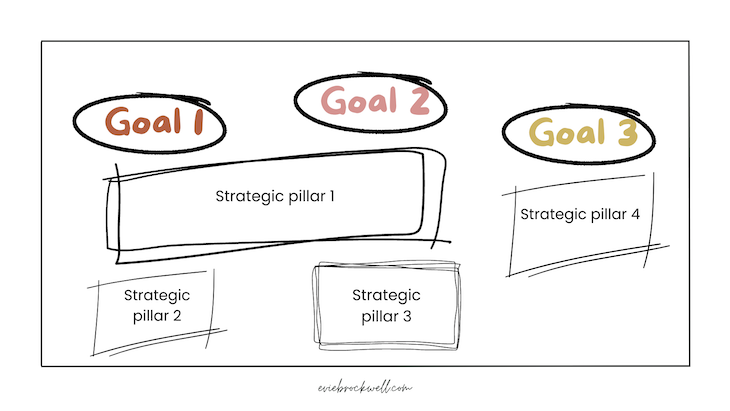

One of the most effective ways to solve this is to use your product strategy to structure your product teams. This allows your product strategy to become the centerpiece of your organizational design.

Most product organizations are set up with teams that are focussed on a particular area of the product, or vertical. This often leads to siloed ownership. Teams are often domain experts and can deliver code quickly in their area. However, they’re also less flexible and agile.

Teams are also often made up of only product, UX/design, data, and engineering. They therefore have other parties sitting external to the team such as sales/commercial, legal, marketing, and customer success. This also leads to siloes across the organization.

As a result, different teams and different departments have competing priorities. This leads to conflicts of interest on what to work on.

The solution? Aligning your teams around the product strategy to unlock value.

To achieve this, you need to have an effective product strategy and a rough implementation plan — meaning that the product priorities have been broken down (at least on a yearly basis). You should have also conducted capability analysis to see where you have gaps and know what kind of teams and skillset you might need to plug these:

As I also mentioned previously, this doesn’t have to be set and done — you can involve teams to get their thoughts and opinions and assess what focus is needed. Just make sure you carve out some time for them to be able to do this.

Now that you have all of your essential ingredients you can start to think about how to align your teams around your product strategy.

For each strategic pillar, you’ll need to assess who you need to be involved to deliver this effectively. For example, if strategic pillar one is about launching your product in a new market then you will likely need to involve:

Traditionally, each of these teams and departments would be separate functions, with their own priorities.

A capability team might operate as a supporting team for multiple areas, and therefore find it hard to prioritize and remain focussed on the main goal, or they might have their own competing objectives.

A commercial team member might have their own agenda, and their own priorities of features that they think would be important to implement (for the good of the overall profits), but as they have their own individual department-led goal, it might not fully align with what the overall priorities are when considering effort, customer needs, marketing, and long-term growth.

You might also find that the skillset and teams need to change over time. This can still work by rolling teams on and off an objective.

You can structure product teams by:

There are pros and cons to each of these approaches.

“Normal sized” is typically a product team with one PM, up to five engineers, a test engineer and the right supporting functions.

Depending on the size of the organization, and complexity of the code base, it could be that one team is sufficient to achieve all of the goals that you need to execute against the strategic pillar.

If the team has the right knowledge and skill set, and can be agile and not pass through too much bureaucracy, it’s likely that they can contribute to different areas of the product either through coding directly in that space or agreeing to merge in code with the appropriate team.

The benefits of this are that:

The downside is if the process / code base is too complex. Having one small team in that instance is likely to mean that the team sees really slow progress.

If your organization is large and complex, and you already have multiple teams that are assigned to different areas of the product, you may choose to retain these team set-ups, but set them on the same strategic goal.

This works well if the teams aren’t expected to contribute to other work or be pulled on to any other strategic pillars.

Teams can then self-align and work out how to work together to contribute effectively to the strategic goals.

If the teams are expected to have their work split across competing goals, and contribute to multiple business objectives, then it can become really hard for teams to remain focussed and make decisions.

Placing more engineers in a team can work extremely well, if the engineering team is self-sufficient, understands the product goals and can make decisions and have conversations to drive their work forward without supporting functions.

This can help to alleviate issues that you might see with speed in approach one, while also reducing the complexity of having multiple teams and potentially different opinions.

Overall, the best approach (or combination of approaches) to take, depends on your organizational set up, processes, and the complexity of the code base.

Once you’ve established the approach you want to take with your product teams, you want to assess how you align with other departments on your strategic pillars.

To achieve this, you already need to be aligned at the strategic level on what the most important goals are.

There are a few different variations of team set-ups that you could try, again, depending on your organization and what you think will work for you:

Working groups are a great way to align people around a strategic pillar, if you don’t need too much dedicated input from these people to achieve that goal. For example, this works great in the kind of example where you might need a small bit of legal input, but you’re not working on something that will be completely dependent on the legal approach.

Working groups allow you to align the right people that are needed to make a strategic pillar successful.

The right people should be involved in creating goals and understanding what needs to be achieved. You can then continue to have regular check-ins with them afterwards. When you set up a working group, people should know what is expected of them to make this goal successful, but they also can reserve most of their time to work on other projects and their day-to-day business needs.

If you need more dedicated time from people — say if they are crucial to the success of the pillar — then you’ll need to explore one of the more intertwined team set ups.

The typical product nucleus contains UX, engineering lead, and the product manager. The idea behind this is that all three of these parties have a stake in deciding the direction and areas of importance to allow them to progress. These three functions will meet up on a more regular basis than the whole team to discuss their insights, learnings and what approaches to take.

This approach can be expanded further to contain other functions that are critical to the success of the strategic pillar. For example, this might include someone from commercial, data, or customer success, depending on the area in which you are working.

With this, you can form a tighter working group that meets more regularly. These people might still have other priorities, however, they’re more dedicated to the success of this strategic pillar than they would be if they were part of a working group. They might have their own personal goals and objectives that highlight the priority of the work that they are doing on this strategic objective.

People in this space should be fully invested and available to make the pillar a success.

This is the best approach to take when people need to be heavily involved in the success of a Product. This doesn’t necessarily mean that people join the product team as a function — it might be that the strategic pillar is led by another department, but they’re fully involved in the product and understand the customer and trade-offs that need to be made to make the product a success.

The idea behind full squad integration is that:

The dangers of operating in this space could be that you have too many people and too many inputs. There is also a danger of involving people in the product team if they don’t fully understand how to do product well.

You might only want to embark on this path if you have a very mature product organization that takes a product-led approach and everyone understands how to do this well.

No matter which approach you take, there are some key elements that you will need to embed to ensure that you successfully align everyone to achieve the goals.

Key steps to work through are:

Personnel, structures and approach might change over time. The crucial thing is to follow some key principles that allow you to constantly evolve and learn the best approach to take.

In essence, don’t worry about getting this “right” the first time. It’s rare that anything will ever be perfect, and as with anything in a product, the best way to learn is by doing.

Keep the following principles in mind:

By aligning your teams around your product strategy, you set yourself up as an organization to make sure that you’re working on the most important areas.

This allows you to live and breathe your strategy and constantly learn what is and isn’t working. Along the way you’ll also reduce silos and focus on increasing the speed that you reach your goals at.

Featured image source: IconScout

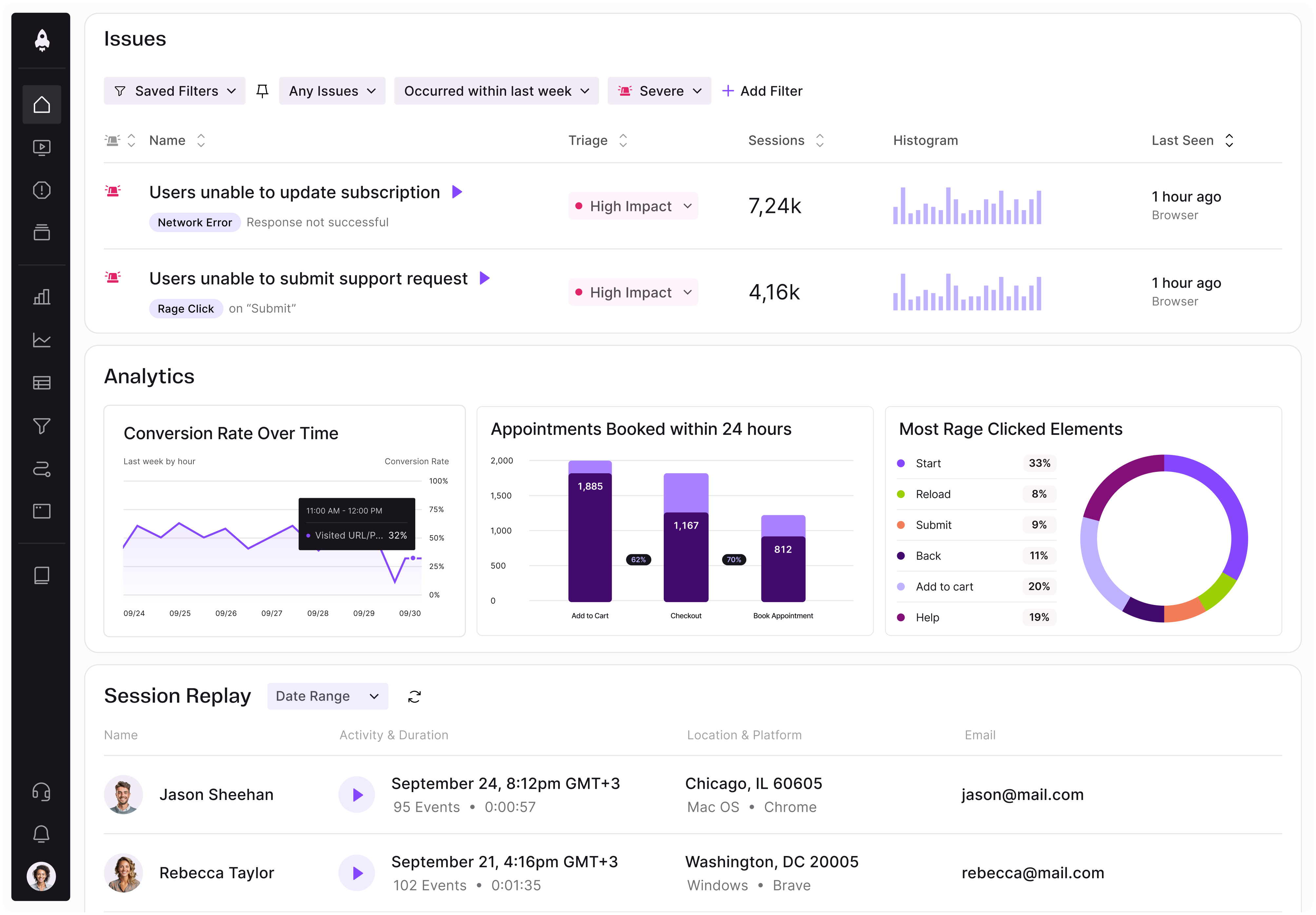

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.