Customer needs can change over time, and it’s important to monitor these changes and address any critical issues that customers have with the product. Customer research plays a vital role in this, and customer exit surveys are one of the most important types of it.

In this article, we’ll discuss what customer exit surveys are, why and when to use them, what to ask, and more.

A customer exit survey, sometimes referred to as a customer cancellation survey, is a questionnaire presented to customers after they unsubscribe (or if they are about to unsubscribe) from a product.

In this article, when we say product, we mean a digital one, such as a SaaS (software as a service) product.

The purpose of customer exit surveys is to find out why customers unsubscribed (or “churned”).

Their purpose is not to discover all of the opportunities for improvement, just the critical issues causing customers to churn. By finding out what those issues are — whether they’re related to features, bugs, design, support, costs, or whatever — and addressing them, you’ll be able to retain more of your future customers.

It’s possible to convince customers to stay using customer exit surveys, but it wouldn’t be the right thing to focus on. It’s usually better to rebuild relationships with ex-customers and put in the work to reacquire them, but we’ll go into that in more detail later.

Customer exit surveys can also help teams identify which customers they should strive to satisfy and which customers might be better off with a different product. This, in turn, helps teams fine-tune their product-market fit (PMF).

Lastly, customer exit surveys can track churn rates over time, revealing how effective the improvements have been.

As the name suggests, you should present customers with customer exit surveys as they unsubscribe from the product, or “exit” it.

It’s important to remember that this survey isn’t for users. We want to hear from the customers specifically, unless it’s for a business-to-consumer (B2C) product where the users/consumers are the customers. Ultimately, it’s the customers, who are the buyers and decision-makers, that matter in this context.

The survey also isn’t for customers that are still using the product, even if they’re unsatisfied customers that are likely to churn eventually, because we don’t just want feedback. We specifically want to know about the fatal flaws and last straws that actually make customers quit.

So, with all of this in mind, customer exit surveys should feature somewhere in the product’s subscription cancellation flow, ideally either in a post-cancellation email or in-app/on-site immediately after the customer unsubscribes. You can see this in the example below from TunnelBear, a VPN provider:

By presenting the survey post-exit, you’ll catch genuine churners who couldn’t be saved, but whose insights will be extremely valuable. They’ve already left, so asking them questions will only result in the same outcome or a better outcome. You’ve very little to lose, but a lot to gain.

However, if you present the survey pre-exit and attempt to retain customers with salesperson language, this will distract you and it’ll be hard to acquire insights. You’ll be spending more time convincing customers to stay than learning about the issues, losing any opportunity to improve the product and prevent more churn. Instead of irritating customers further, make sure that their last impression of you is a positive one, as this will help to reacquire them later.

That being said, some customers do rage quit — especially when they encounter problems they can’t fix. This is more common with free trial customers, but it doesn’t hurt to link to FAQ and help sections where relevant.

The best product teams are those where everybody feels comfortable diving into the product’s analytics, identifying opportunities for improvement, and raising any concerns to the team. With that in mind, anybody can suggest that a customer exit survey might be necessary.

However, it’s usually product managers that will decide to implement a customer exit survey. They usually do this after confirming that the churn rate has room for improvement and that improving it will yield a worthwhile return on investment (ROI).

It’s best to implement customer exit surveys sooner rather than later (before you need them, in fact) since there’s a natural limit on the supply of churners. Don’t wait until everybody has churned.

The resources needed to carry out customer exit surveys are pretty minimal. You’ll only need one team member to get this off the ground (using free tools), but I’ll walk you through a slightly more ideal setup that splits responsibilities between various team members.

Firstly and most obviously, somebody needs to write the questions. Getting an interviewer to ask the questions won’t be necessary since the survey is unmoderated, so customers can fill it out by themselves in their own time. That being said, fallacies and biases can find their way into questions just as much as they can find their way into answers. Various team members should look over the survey to make sure that they ask the right questions in the right way.

Implementing the survey would most likely require a developer, although this would be a one-time thing.

The team that helped write the questions are most equipped to synthesize the results. To effectively analyze the data from a variety of perspectives, however, it’s best to divide the responsibility equally rather than having one person take the lead.

Finally, nominate one person (any person or the lead person) to follow up with respondents if necessary.

Product managers will need to source the right tools. This is fairly easy as any survey tool will do. SurveyMonkey, Typeform, and Jotform are all great choices, however, there’s nothing wrong with Google Forms either, plus it’s free.

If you’d prefer something more suited to product research (with prewritten but customizable survey templates and other templates/features for research and testing), you’ll definitely want to look at Useberry, Maze, or the new kid on the block Ballpark (made by the awesome people at Marvel).

It’s just a survey, so don’t get hung up on comparing the tools too much. If you’re feeling a bit paralyzed by the options, just go with Google Forms.

Product managers should also decide upon some kind of incentive, if possible, to persuade churners to take the survey. This incentive shouldn’t be product-related — you don’t want to create the impression that your only focus is to entice them back. Act like you want their insight, not their money, and instead offer a cash/voucher reward or donation to a charity on their behalf.

Delegate writing a heartfelt message that expresses sadness that the product wasn’t able to live up to their expectations, explain why you’d like them to take the survey, and then offer them the incentive before presenting them with the survey.

First, confirm that the respondent is the decision maker and not just somebody tasked with canceling the subscription. If the tool you’re using has a conditional logic feature, you can forcibly end the survey if the respondent doesn’t qualify.

Next, get straight to the point with “What made you cancel?” This should be an open-ended, qualitative question that lets respondents really open up about what the main issues are and immediately make them feel heard. Here’s a great example from Jotform:

After that, you’ll want to ask “what did you like about the product?” and “what didn’t you like about the product?” This is just more of the same but is crucial if we really want respondents to paint a picture of their experience. With these questions, respondents are more likely to list specific grievances, such as bugs or poor customer support interactions.

“What specific improvements would you make?” is a fantastic way to eliminate some of the guesswork and make synthesization way easier.

“Would you reconsider our product in the future, and if so, what would that take?” is essentially the first question but slightly reframed for additional validation and to focus more on what might happen after, rather than what’s happened already.

“Who would you say the ideal customer for our product is?” focuses slightly more on the product-market fit. This may reveal that the product isn’t meeting the needs of the target market or that you’re targeting the wrong market.

You’ll want to keep the survey short and sweet to maximize completion and minimize analysis paralysis (i.e. having too much data to analyze), but if you think that there’s more to ask, feel free to include some additional questions.

Rachel Andrea Go’s exit survey question bank lists some fantastic extra questions. Just remember that new information doesn’t necessarily mean useful information — be mindful of what you’re asking and don’t let the FOMO of information get the best of you. You can always reach out for more information afterward.

To wrap up the survey, remember to collect the respondent’s email addresses so that you can follow up with them regarding their answers, attempt to reacquire them later, and/or find out whether they switched to a competitor and why.

Customer exit surveys are extremely common, but only a handful of them yield actionable insights and an even smaller number of them result in positive actions. It’s important that customer exit surveys don’t become a tick-box exercise for product teams. This will only create the illusion that a product is propelling forward. This means synthesizing the data correctly, turning them into actionable insights, and then taking action.

First, scan the responses and try to put respondents into one of three groups:

After that, you’ll want to synthesize the data, or more specifically, group-related concerns (voiced during the main “why did you cancel?” question) to make them easier to digest and then order the groups by size. Addressing the largest groups will satisfy the most churners, which, of course, you’ll do using all of the qualitative data across all of the questions.

Next, vote on what to implement first, factoring in ease of implementation and customer demand. Engage all of your normal product design processes (e.g. prototyping, testing, etc.).

The team has fully implemented the changes! Now what?

Firstly, you’ll want to confirm that the churn rate has increased, which takes some time. Avoid making any changes during this time so that you don’t invalidate the experiment.

While waiting for new data to build up, acquire some qualitative feedback by reaching out to the customers that originally lifted the lid on the issue. To hit two birds with one stone, award them with free access for a limited time and ask them to test the changes. Who knows, maybe they’ll come back once their free access has expired.

Perhaps you’ve heard of customer exit surveys before but never implemented one. Maybe you’ve implemented one without also implementing a process for studying the results and making positive changes based on them. Or maybe you’re a pro that’s constantly looking for ways to improve their process.

Regardless, I hope you took something away from this article. If you have any tips of your own you’d like to share, you can do so in the comments below. Thanks for reading!

Featured image source: IconScout

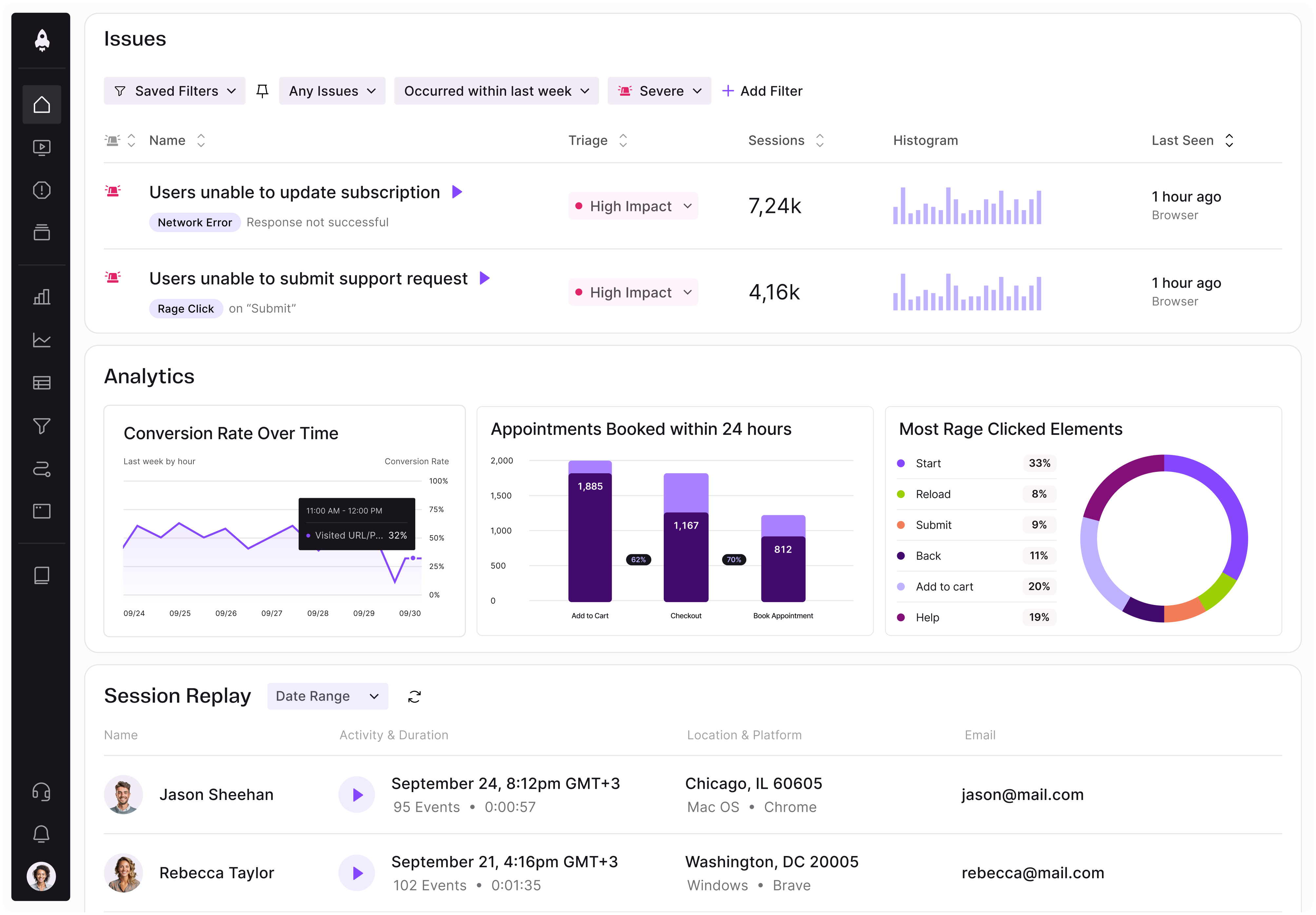

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

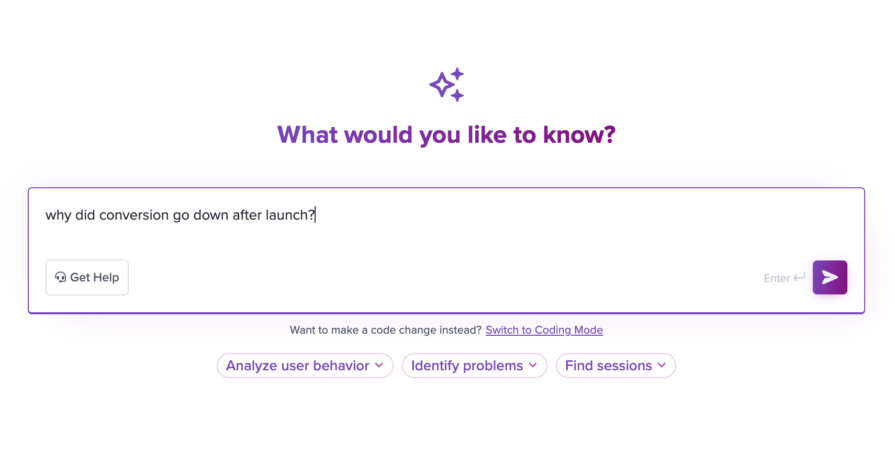

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.