Aspiring product managers often think that most of their time at the helm of their product will involve creating and polishing new features. While development plays a significant part in the role, the truth is that it’s mostly a job about getting people to agree on stuff.

Ultimately, you need your team to stand behind you and buy into your vision for the future; you have to agree with your manager on your goals; you need to convince other teams to cooperate with you on your dependencies; and you even need your customers to agree with you that your product delivers value.

No wonder it’s seldom smooth sailing. Product management involves diplomacy between different people with different agenda, egos, ideas, conflicts, and mistrusts. In the end, it’s not about surviving the dispute, but finding a solution for everyone and resolving any animosities.

To help you navigate through these waters, this guide covers some of the biggest sources of stakeholder conflicts and then explains how to fix them. I also walk you through ways to build stakeholder trust.

Before unpacking how to build trust, it’s important that you understand how to identify and fix common sources of conflict. These include:

Misaligned goals sit at the core of most stakeholder conflicts. Everyone works toward the success of the company, but their definitions of success rarely match. This especially holds true for you as a PM who has to cater to the needs of different, competing teams.

Without the right authority and independence you can become frustrated. You should be empowered to say “no” when the situation demands it. Without this tool, the misaligned goals of different stakeholders will likely lead to product promises that can never be fulfilled or subpar releases.

How to fix it:

The product manager should have the final decision on the shape of the product roadmap. Stakeholders need to provide requests, not demands. Of course, there’s some wiggle room and negotiations should lead to the best possible solution.

However, all parties need to understand that the final outcome is a compromise that can be improved only by getting more developers or dropping the quality. In most cases, neither are possible options, so the compromise can stand.

Another good solution would be to unify your metrics by using the so-called “North Star” metric across all teams and projects. In such a case, whenever a request comes to you, it should also come with this metric’s impact estimation. This leads to an easy and transparent prioritization process.

Ever heard any of these before?

Miscommunication isn’t just about poor updates. It’s about failing to give stakeholders the context they need to trust your decisions. If execs, sales, or engineering teams don’t understand why certain choices are made, they might assume the worst.

After all, great communication involves providing the right amount of detail to the right people, via the right medium, at the right time.

If you lack transparency this becomes especially tricky. For one crowd, you can be too transparent by providing too many details and, in turn, lose their focus and the opportunity to deliver the intended message. At the same time, provide a high-level, detail-less explanation to your developers and they will be really upset.

How to fix it:

Create a stakeholder map or similar document that you fill in with the way they will be updated, how often, and at what level of detail. Of course, it’s best to do this when you just joined a company and things are only starting to kick off. You may ask other PMs and your manager for help here, or simply monitor the updates to certain stakeholders that you were CCed on.

You may also want to set yourself a reminder, perhaps in your calendar, about upcoming updates to certain stakeholders.

On top of that, it will be super helpful to record all the numbers and reasons behind your decisions. This will help you trace your steps later and also better explain to stakeholders why certain directions were taken. Even if you can’t recall the numbers or didn’t plan to talk about them in a presentation, there’s always a document waiting to fall back to.

If you’ve ever had an exec “request” a feature that engineering says isn’t doable, or had sales insist on a rushed update that design says will break the UX, you know this conflict well.

There’s often a disconnect between what stakeholders assume is “just a small change” and the actual effort. I will always recall the time when it took three months to update the look of the main call controls in Skype (no wonder it’s shutting down in May 2025).

This conflict usually starts with business teams that don’t always understand technical debt, development standards, the release process, and other cult-like-sounding elements of the product coding process. And who could blame them when common sense tells you that updating three buttons should be an easy job…

Also, why is taking new requests paused for something called refactor? This leads to engineering getting frustrated and rushed, while the rest of the company complains that development takes forever.

How to fix it:

I believe this is the hardest point to address and a big point of content for many product managers. Most likely, your business stakeholders don’t care about the technical side of things (unless it’s really affecting the business), so it’s best to keep the KTLO (keeping the lights on) tasks and details away from their task. They just need to know that every car needs maintenance or it’ll die and KTLO is exactly that.

To achieve this you may choose to ignore KTLO on your roadmap presentation (only mentioning those tasks and minor, background tasks) and/or bloat the effort necessary for business effort. The safety margin created in this way will allow you to peacefully allow your devs to work on their tasks.

Remember to always focus on the value to the business and users when talking about technical maintenance tasks. If you struggle to find it, then perhaps indeed it’s worth rethinking the task where the impact isn’t clear.

Businesses love predictability. Thus, high-level managers want clear timelines, milestones, and deliverables. Agile teams, on the other hand, should work iteratively, adapt to new discoveries, and shift priorities as needed.

This obviously creates a natural friction and often makes a mockery of agile scrum transforming it into a hidden, unnamed waterfall way of work. You can’t be agile if you’re required to commit to exact deliverables every three months.

How to fix it:

Well, there isn’t a good solution to this conundrum, but let me share a few strategies that worked for me in the past.

One thing that can make a difference is to simply watch your words. You aren’t committing to a three month roadmap! You’re presenting a draft of a roadmap for the next three months with possibilities for future updates. Given all the unknowns and potential difficulties ahead, you’re never able to present a fool-proof plan anyway.

Another thing that’ll help is to update the stakeholders even on potential delays. The earlier they know the risk, the more accepting they’ll be if the development extension actually happens.

A final suggestion for this problem is to speak in your stakeholders’ language. Here I mean money or whatever is the main metric they’re chasing. If they understand the opportunity, they’ll gladly accept any roadmap changes.

However, like most of the pieces of advice in this part of the article, these are just cures for fixing the symptoms. The true source of conflicts lies in the lack of trust in the product manager. It might be a better strategy to work on gaining this trust so that you have the benefit of the doubt for every single, potentially controversial action, you might take.

Different PMs start with varying levels of trust with their teams. You grow trust through consistency, transparency, and advocacy. In other words: by being an actual part of the team.

You don’t need to be a developer or designer, but you do need to understand their challenges. Take the time to learn about different technical constraints, what makes a well-structured design, and how different teams approach problem-solving.

When you speak their language, they’ll see you as a partner, not just a meeting organizer. At the same time, don’t try to be an expert and know better than them. The line between healthy challenges and being full of yourself is thin.

Nobody wants to feel like they’re just executing tasks without context. Make sure engineers and designers are involved in roadmap discussions before anything is finalized. Ask for their input on efforts, risks, and potential alternative solutions.

When people feel heard, they’re far more likely to trust your leadership. Moreover, if they’re part of a difficult decision, they’ll help you deal with the consequences rather than see you as part of a problem.

If your team doesn’t understand why something is important, they’ll be less motivated to build it, especially if they disagree on the direction. Explain the client impact, business value, and goals attached. Show them your prioritization process and allow them to comment if you missed anything.

If you change priorities later, clearly communicate why things have changed to maintain credibility.

When things go wrong (and they will), don’t blame your team, even when they’re the culprits. Take responsibility for decisions, acknowledge what could’ve been done better, and focus on solutions.

At the same time, protect your team from unnecessary pressure. If senior stakeholders are unhappy, take the heat instead of throwing your team under the bus.

Engineers can spot any BS from a mile away. Don’t present fake, corporate enthusiasm. Just call things for what they really are. Don’t pretend to understand something if you don’t. Instead, ask questions instead.

Also, nothing erodes trust faster than a PM who says one thing in leadership meetings and another to the team. If you stay honest and transparent, they’ll respect you.

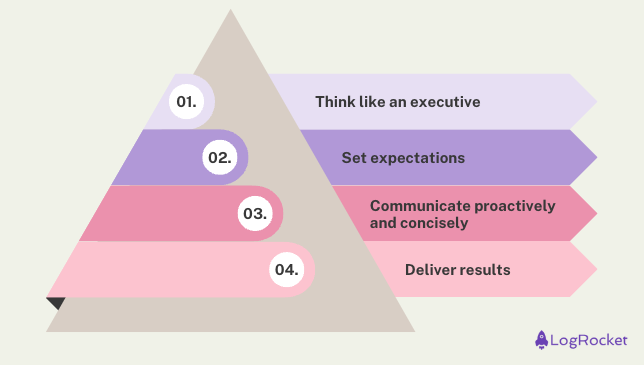

Gaining the trust of your team is only one part of the puzzle. Ultimately you need your senior stakeholders to buy into your product vision so that they continue to fund and support your endeavors. To help with this, make sure that you:

Senior stakeholders care about business impact, not just product execution. When you present ideas, frame them around metrics they care about and understand. Anything else will be mudding the water for them. It doesn’t matter if a feature might be technically impressive if it lacks clear business outcomes.

It’s not because they have tunnel vision — it’s because it’s their job and yours is to deliver and keep the product running. In the exec’s world, KTLO becomes a binary value, and if it’s positive, the business metric(s) is the only thing that matters.

Every stakeholder wants their request prioritized. The key is to set clear, realistic expectations ahead of time. Explain how your prioritization process works and be transparent about why certain things make the cut while others don’t. The more structured and data-backed your approach, the less pushback you’ll face.

It’ll also help other stakeholders understand the gravity of the prioritized items, which can transform a shouting, opinion-based match into a data-driven analysis about the most promising items to develop.

Executives require the most basic communication possible. You should have the details ready in case they have questions, but your senior stakeholders are simply too busy to dig into any context. If you provide only the information they need to hear, you grow as a partner in their eyes.

Nothing builds trust like keeping your promises. If you deliver on your promised roadmap quarter after quarter and the projected business impact is there, you’ll earn yourself the benefit of the doubt for future product decisions. Of course, you can help yourself a little by artificially bloating the effort required to code something or underestimating the metric’s growth.

This is known as Scotty’s principle and I assure you; it’s not about cheating in this case. It’s about leaving yourself some safety margin for the unknown and benefitting when that margin doesn’t need to be used. Frankly, very often even that won’t be enough, but that’s a story for another time.

Friction between PMs and stakeholders is likely unavoidable. At the same time, it doesn’t have to be destructive. The best PMs don’t just push back on bad requests; they proactively align stakeholders around a shared vision and practice the best forms of communication.

At the end of the day, everyone, from execs to your team, wants the same thing: a successful product. The key is making sure that everyone understands what success actually looks like, and how their role fits into the bigger picture. On top of that, seeing the big picture, whether at a quarterly meeting or during a development kick-off meeting, is the best solution to work in harmony with making the product vision happen.

Thank you for reading another one of my blog posts. Be sure to come back soon!

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.

How AI reshaped product management in 2025 and what PMs must rethink in 2026 to stay effective in a rapidly changing product landscape.

Deepika Manglani, VP of Product at the LA Times, talks about how she’s bringing the 140-year-old institution into the future.