In this guide, we’ll define product adoption, explain at a high level the purpose of a product adoption strategy, and describe some real-world examples to show why a product adoption strategy is especially crucial in B2B environments.

Product adoption refers to the process by which users become aware of a product, determine the value it can provide, and, ultimately, decide whether to use it on a recurring basis or stop using it altogether.

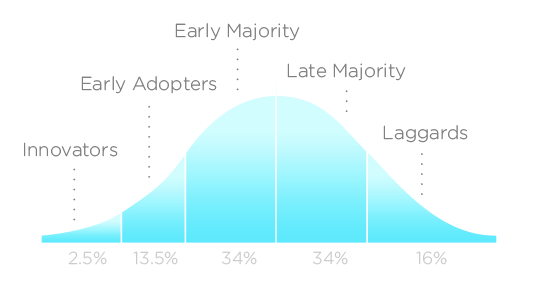

The product adoption lifecycle is often visualized as a bell curve consisting of five stages:

Product strategy generally identifies key partnerships, target personas, initial market segments, and beachheads. A sound product strategy must also include an adoption strategy that considers the end-to-end business process clients currently use to manage their jobs.

For example, taking an aircraft manual and digitizing it without considering how pilots train will result in a low adoption rate.

While this example might be obvious, it barely scratches the surface of a much larger issue in B2B environments: considering (or failing to consider) the fact that these environments often include multiple stakeholders, systems of truth, and employees can make or break the success of your B2B product.

Over the last several years, the cost of digitization has gone down considerably, making it accessible to a more extensive market segment. Startups and incumbents alike have shown tremendous innovation that can unlock value for their clients. The solutions offer a demonstrable return on investment and improve end-consumer experiences, boosting their client’s top and bottom line.

Full-service providers, such as Guidewire for the insurance industry or Sabre for the hospitality industry, provide an overarching fabric that makes it the system of truth for their employees.

The ubiquitous connectivity enables new ecosystem drivers and incentives to stay attached to the end-consumer in new ways, with the opportunity to offer point solutions without being a full-solution provider. This opportunity, in turn, makes it attractive to spin off new products that enable micro-transactions and incremental revenue opportunities.

Recent examples of such drivers include smartphones, which now can take high-resolution pictures, minimizing the need for physical inspections. NLP bots are plug-and-play, and they can access information systems and drive the next-best-action (NBA) effectively, in several cases without human intervention.

Why do so many product launches fail, then? It might be tempting to write the product off as lousy, but quality isn’t always the root cause. As Alberto Savoia put it so well in his book, The Right It, products are often unsuccessful due to failure on launch, operations, or premise (FLOP).

Let’s consider an alternate perspective. Organizations typically have existing processes for a job from start to finish, and any deviation from this is generally undesirable.

In highly regulated industries, such as insurance, a solution that alters the flow can cause resistance, no matter how solid its value proposition is. It entails changes to the business process, training employees, and, sometimes, training their customers on the new process. Imagine training 5,000+ employees and 20 million customers for a large auto insurer to give you an order of magnitude.

This example demonstrates the need for an offering to fit into a more extensive business process beyond the clear benefits, be intuitive to use, and be simple to train everyone on.

A secondary issue is with the coverage the offering can provide. While the ROI might be substantial in the cases where it applies, the amount of process restructuring required to solve a minority of the use cases might not exceed the adoption threshold.

Relevant questions that often come up in this context include:

In my point of view, product managers need to:

A few years back, awareness of employee abuse by customers, notably in the hospitality space, rose and began to surface in public discourse. A 2016 report revealed that 58 percent of hotel workers reported having been sexually harassed by a guest, and resultant lawsuits reportedly exceeded $1 million. The American Hotel and Lodging Association (AHLA) quickly stepped in to create a process for hotels to install panic buttons for employees.

Several startups (Track-n-Protect) and incumbents (React) saw the opportunity with a market of $500 million in hardware TAM and $100 million in recurring revenues. The hardware was unsophisticated; installation partners were available.

Despite their simplicity to use, regulations, and reasonable costs (a TCO of $20,000–30,000 over five years), they haven’t penetrated the market. You could blame covid for lack of adoption — I know that to be a factor, but to blame the pandemic entirely would be myopic.

Here’s where the real failure occurred: the focus was on the product specifications, lowering costs, and UI screens rather than integration with existing systems that the front desk and back-office employees used.

Imagine explaining to a front desk employee that they would need to switch to another system, review the situation, and act swiftly in an emergency. It doesn’t matter how they were trained; their muscle memory would force them to reflexively do what they knew best. The back-office team would need to file a report with law enforcement.

Having them switch to another, alien system would also cause adoption friction. The consideration for deployment beyond the hardware installation should consider configuration within the source of truth (Sabre or Amadeus) and the ability to present the condition within the same system as well — including providing the ability to pull an integrated report using information from all systems.

Stated differently, the lack of an integration perspective to a point solution in an existing business process foreshadows the failure of an otherwise good product.

On the brighter side, Tractable AI offers a product to use photos to identify damage and predict a repair estimate. On the one hand, they leveraged the ecosystem (pictures from a smartphone, AI-based prediction frameworks). They understood the importance of their solution within the overall business process.

This astute understanding led them into market segments (digital native insurers such as Root), where they quickly proved value. They then expanded into larger carriers, such as GEICO, and integrated into systems such as Guidewire to offer a seamless solution.

When a vehicle is a total loss (roughly 5 million are every year in the US), insurers must consider complex scenarios, and the paperwork can be mind-boggling. At an average of about 10 years, roughly 50 percent of these vehicles could still have an outstanding loan.

Some states allow a digital signature in all cases; others allow it conditionally (based on loan status). Some states require notarization, and a subset allows electronic notarization. About 20 percent of these total losses can be digitally enabled end-to-end, realistically speaking.

Simply offering an e-signature solution seldom drives adoption. It requires an end-to-end mindset and a short-term solution that streamlines the process flow (and, in fact, from the client’s point of view, makes it look like the same process, no matter the situation).

This type of transformation is massive when you look at it from an insurer’s perspective. The underlying economics are strong.

However, it disrupts the fundamental business process. When the offer presents a way to collect the signature electronically but shifts the employees to switch between two methods, it dilutes the value proposition and tremendously increases the barrier to adoption. Remember, the ROI is from the 20 percent of total losses, not the remaining 80 percent.

A way to solve this situation and drive market penetration is to make the process appear the same from the insurer’s perspective, even if that initially implies a considerable cash infusion.

Identifying an alternate set of partners might be a good starting point. Initiating a strategy with a highly incentivized partner that has the potential to ride with you on the long-term journey makes it even more effective.

For example, if one vendor provides a suite of tools that enable you to autofill the paperwork and digitally send the ones the consumer can sign directly. The automation will send the remaining paperwork to the consumer through a physical printing aggregator. An operations arm could then handle any exceptions. This operations arm might have to do some heavy lifting initially.

It’s the product manager’s responsibility to determine what the five-year horizon should look like:

Overall, is a positive net present value (NPV) demonstrable, and what’s that breakeven point? Does the company have the mindset and ability to take this on? These would be key questions to answer.

Several evaluations are critical when considering a solution to a problem. Assuming the problem is viable, feasible, and desirable, usability needs to transcend the typical UX framework of “good UI.”

Domain and business process knowledge and the ability to keep it simple and consistent in almost all cases tremendously increases the probability of success.

Featured image source: IconScout

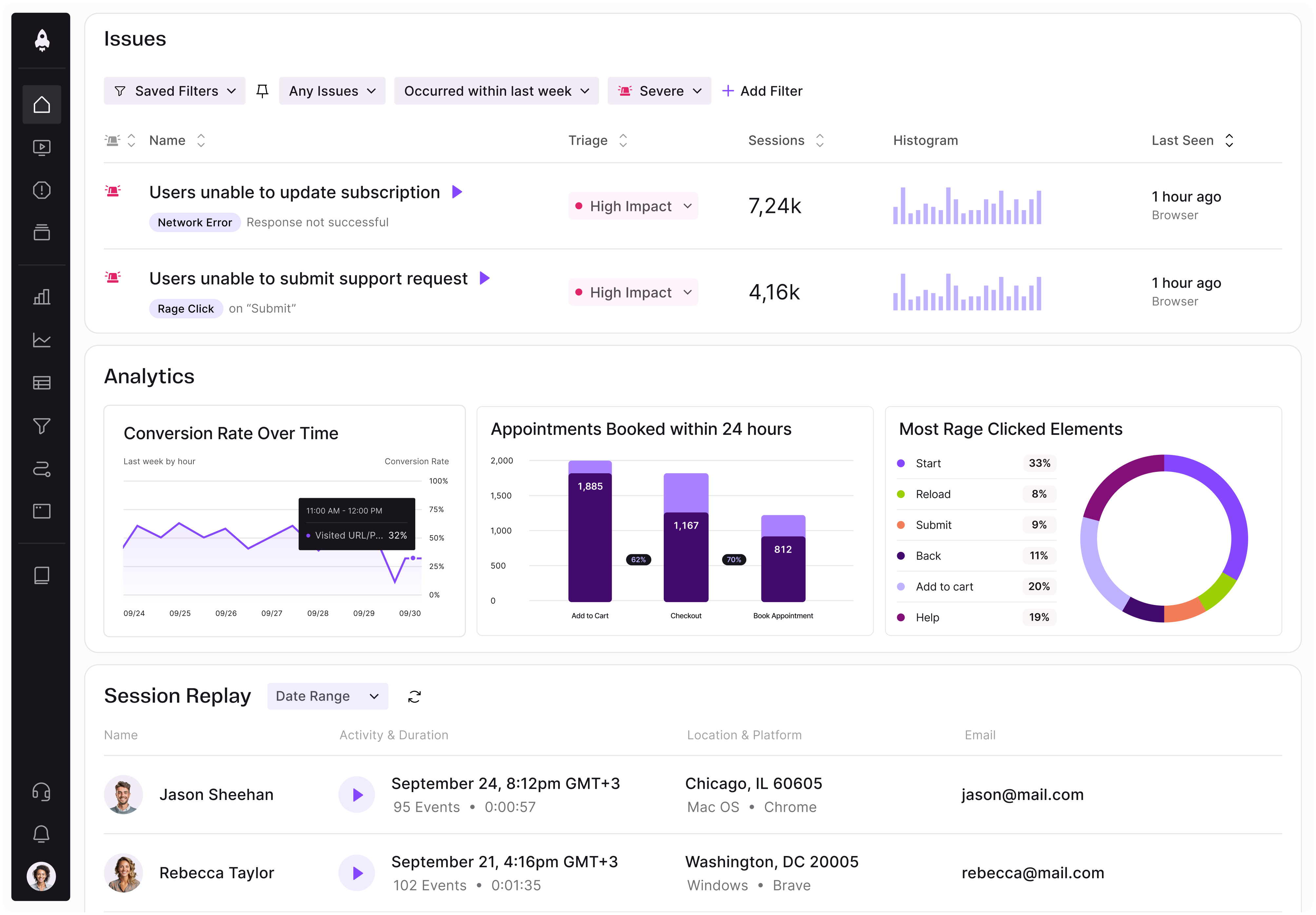

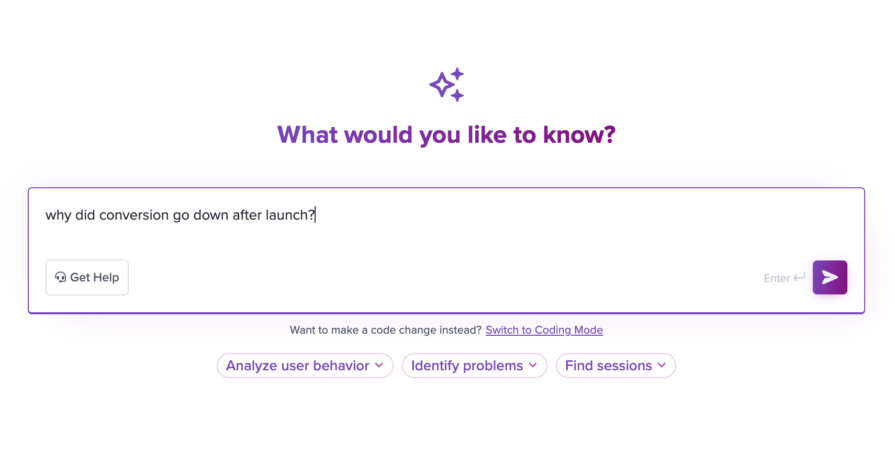

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Learn how to spot PMF erosion early, diagnose the cause, and help your product recover before decline turns into panic.

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.