If you search on job boards, almost every product management listing asks for “strong communication skills.” These postings show up all the time, but what do they really mean?

While communication skills can be hard to quantify, there are frameworks that have consistently shown results. One of these, the SCR framework, was developed to provide a way to effectively communicate with and across teams.

In this article, you will learn what the SCR framework is and how to use it, as well as read examples of how it has worked in the past.

The SCR framework is a model to deliver strategic communications. The acronym stands for situation/complication/resolution.

It was developed by McKinsey & Company as a tool to provide consultants with the clear, specific, and straight-to-the-point communication skills they need to effectively work with clients across various industries.

Although developed with consultants in mind, the framework can easily be applied to other roles and industries, including product management.

As a PM, you are faced with various situations that require effective communication such as, 1-on-1s, presentations, and team and stakeholder meetings. Your ability to convey your thoughts, pitch ideas, explain challenges, and escalate problems strongly contribute to your impact and position within your company.

There’s a reason why “communication skills” are listed in every product management job post. Mastering communication skills is one of the fastest ways to fast-track your progress and position in the company.

The SCR framework consists of three main parts:

You start by sharing the situation, then proceed to explain the impact of the situation, and then wrap up with a proposed resolution or a summary of action points that were made.

Start by describing the current state of things.

Although it might be tempting to jump straight into solutions, if you are engaging with other people for the first time, you need to provide them with context. The additional context will increase the chances that they’ll have helpful suggestions and recommendations you didn’t think about.

Remember to focus on facts. Avoid giving your opinions or interpretations — it’ll only make the context muddier, thus harming other people’s ability to process the situation objectively.

It might also be worth explaining the origins of the situation in a few words. This will help people have a clearer picture of what’s happening.

Depending on the type of situation, the person you talk to, the goal you are trying to achieve, and the situation’s urgency, a situation description might be as quick as one or two sentences or as robust as a detailed report.

This part of the framework addresses the impact of the situation and helps explain its relevance.

Don’t assume everyone understands the situation similarly. Imagine a QA coming to you and saying, “I found a bug.”

That doesn’t tell you much. Not only does it lack context (such as the type of the issue and if it’s a production one or not), it lacks a clear picture of its consequences. You don’t know if:

Always present a clear picture of why the problem is relevant and how it impacts what the people you talk with care about.

If possible, focus on facts and data. The fact that you find something “critical” doesn’t mean it’s critical in other people’s eyes.

Once you’ve explained the situation and gone deeper into the complication, you should shift toward presenting the resolutions.

There are two main types of resolutions depending on your orientation:

If you are summarizing a situation that has already happened, try to come up with a robust version and a brief overview. This will allow you to present the appropriate level of detail to the particular audience.

There’s a high chance the message will be read by various people interested in different levels of details. Some will just need a high-level understanding of the resolution, while others might need a detailed explanation with a justification of why a particular approach was chosen.

One option is to include a bullet-point summary with hyperlinks to more detailed explanations.

If you are communicating orally, ask what level of detail your audience is interested in. As a rule of thumb, start with a summarized version and add details if additional questions arise.

On the other hand, if you present action points toward resolving the situation, the structure depends on the goal you try to achieve with the communication.

If you just want to inform others, provide a summarized version and answer any follow-up questions.

If you are consulting others, I recommend the following structure:

Clear expectations are key. If you need approval, clearly ask for it. If you need escalation or opinion, make sure it’s clear from your message.

Without clearly stating what you need from others, you’ll waste everyone’s time by gathering unwanted input and advice.

Now that you know what the SCR framework is, here’s two examples of how it can be used in practice:

Let’s say you made a backend configuration change that resulted in production issues that you then resolved. Now you are writing an update for stakeholders It could look like this:

“We were shifting our subscription plan configuration last Thursday at two (situation). An hour later, we noticed purchases weren’t coming through (complication). As a result, we had 50 failed purchases an hour, resulting in a $3,000 new sales revenue loss each hour. After realizing that our configuration change resulted in unexpected server errors, we decided to

roll back the change and contact customer support to explain the situation (resolution).

We estimate the new sales revenue loss at $4,200. We have a post-mortem on Monday to understand why this happened and how we can prevent that in the future. I’ll update you afterward”

This communication addresses the situation, complication, and resolution, allowing you to convey a lot of information in a short message.

Anyone reading this can understand what happened, why it happened, the impact, and how the situation was resolved. Although some details might still be missing, those receiving the message have a clear picture that there’s a post-mortem planned, and they can expect a more detailed summary soon.

Now, let’s imagine you want to pitch an idea to build product onboarding in the next quarter. A pitch structured in an SCR method could look like this:

Challenge:

Proposed solution:

Action points:

It’s worth noting that this example doesn’t follow the SCR structure to the dot. In the challenge section, there’s mostly a situation description, but also a bit of complication assessment. The proposed solution gives complications and possible resolution, similar to action points (situation: retention team blocking change; resolution: CPO escalation).

But on a high level, it maintains the flow of giving an overview of the situation, then explaining various complications, and ending with the proposed resolution.

Ultimately, the SCR framework is not about firmly separating its three components. It doesn’t make sense to force-fit communication into a given structure if you communicate on a complex topic that cannot be easily split into three parts.

However, keeping the SCR structure and principles in mind, the message walks the reader through all critical parts of clear communication without an abundance of needless words, and that’s what’s important.

Communication is one of the most essential skills of every product manager.

The clearer you can communicate, the more buy-in you can get, the stronger position you can build in the company, and the more time you’ll save on misunderstandings.

One of the tactics to level up your communication is to embrace SCR principles by:

As we saw in the examples, the ultimate goal of SCR is not to prepare communication with a clearly separated situation, complication, and resolution. It’s to give a high-level structure to your messages, focusing on the most important details and avoiding any needless and wasteful communication along the way.

Keep practicing the quality of your communication, and I guarantee your career and performance as a product manager will improve dramatically.

Featured image source: IconScout

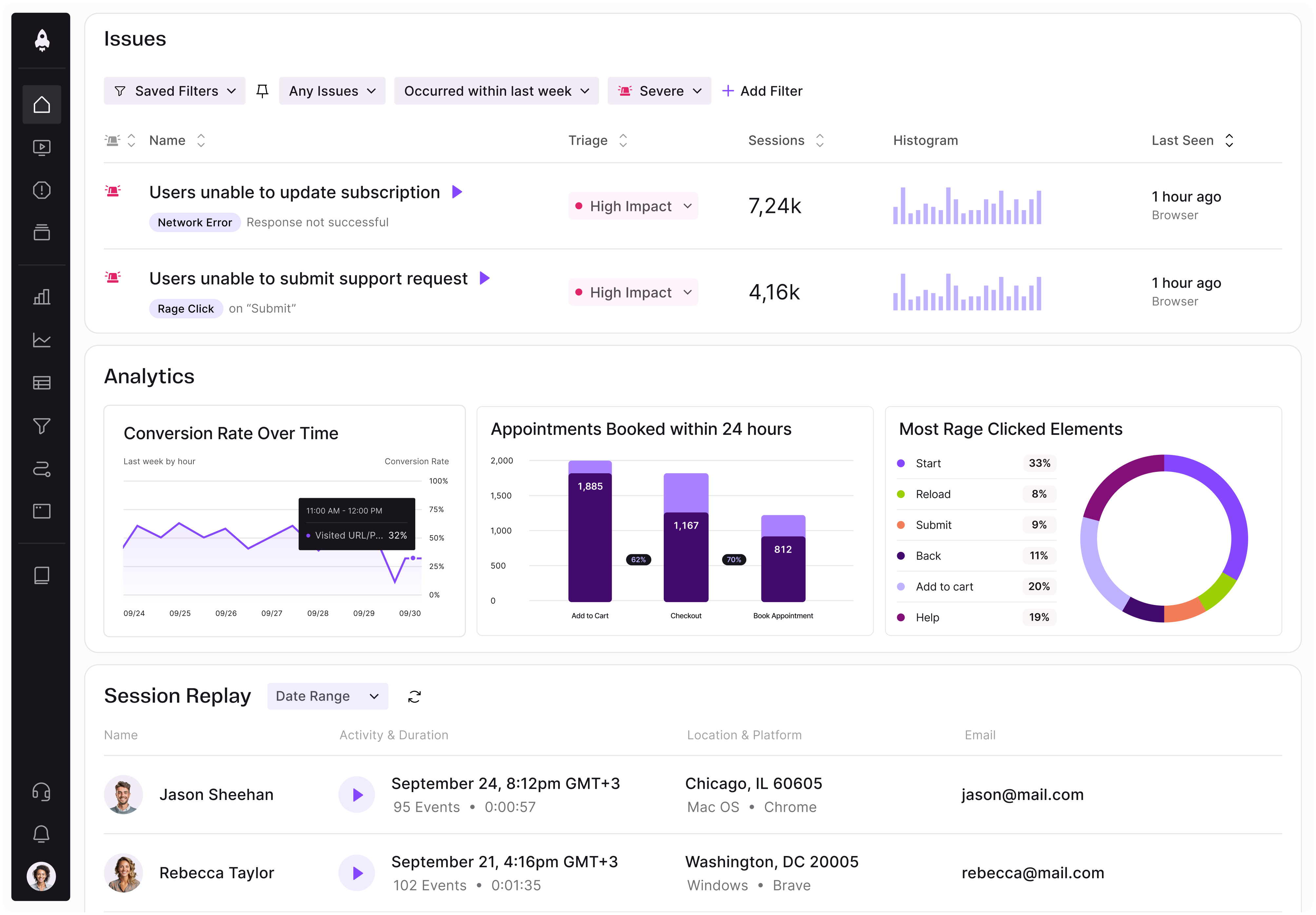

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.