Over the last decade, I’ve had the chance to be a product manager in many different organizations, from start-ups to well-established companies. Each place played the game differently, and product managers had particular traits depending on the scenario.

What I can say though is that there are more product manager positions in scaling companies.

In this article, I will help you understand what being a PM in a growth stage means. However, first I will need to illustrate the differences between start-up and scaling PMs.

You can differentiate the two on the basis of these five categories:

Before I jump into the difference between the two company scenarios, let’s elaborate on what my roles looked like:

When it comes to focus, the flight level is considerably different for start-up PMs and scaling ones. A start-up aims to prove market fit, which requires adapting the product frequently, whereas a scaling company seeks to grow the business sustainably. Each scenario requires a different focus.

Considering the start-up PM I mentioned, I looked at different audiences: car dealers, car owners, mechanics, negotiators, etc. Each interacts with the product in a different way, and I’d determine how that contributed to our ultimate goal.

To accomplish this, I’d talk to many people and try several ideas quickly, throwing out almost all of them.

The scaling PM I referred to needs laser-focus. My mission was to improve partner onboarding to reach our acquisition goals. I’d work on a precise audience with a crystal clear goal.

Day in and day out, I’d focus on how to get closer to the numbers I needed.

The start-up PM jumps between audiences and has a broader focus, while the scaling PM will have a laser focus with a clear audience. The depth differs. One goes shallow, and the other goes as deep as necessary.

Progress and learning are paramount in a start-up, which means that empowerment is necessary to succeed. Although empowerment is vital for scaling up companies, having more hierarchy levels and requiring discussions before calling the shot is normal.

As a start-up PM, I’d try several experiments in the same week and drop most of them. I wouldn’t have to align with anyone apart from the founders. I’d agree on what we had to learn and go for it.

This allows you to be empowered to decide what to do and how to do it.

In scaling companies, it’s unlikely a PM can call all the shots alone. Most likely, there will be a few hierarchy levels.

I had, for example, a product lead and chief product officer who would like to be involved in anything that meant pivoting. I spent more time elaborating on my decisions than progressing. Without support from my manager, I couldn’t move.

I was empowered to address different solutions related to the goal I was assigned, but whenever I uncovered a further opportunity that required alignment.

When I worked in a start-up, the process was chaotic. Often there weren’t recurrent meetings or precisely defined roles. We had our Kanban board, and once a day, we’d look at it and align what to explore, and we went from there.

As a start-up PM, I’d focus on collaborating with others and progressing at lightning speed. I’d make my calendar highly dynamic.

Looking back, it was stressful not knowing what to do next, but fun stepping into the unknown and uncovering multiple opportunities.

The scaling organization is more complex because more people are involved. In my scaling PM life, there was nothing like a start-up.

We worked with Scrum, and I had recurrent meetings on my calendar with Scrum teams, stakeholders, and other PMs.

Some days were like the others, and sadly, when I got distracted, I realized I started following the process for the sake of it and not because I needed it.

Over the years, I learned that finding harmony between process and chaos is essential. With rigid processes, teams lose creativity, and without any, teams become inefficient.

When I was part of a start-up, the word stakeholder never came to my mind. We were 25 people, and we knew each other. Collaboration was easy because we shared the same objective. Yet, in a scaling company, we were 250, and I didn’t know half of them. On top of that, we had different objectives, which complicated collaboration.

In start-ups, alignment is fundamental. You know the goal and align with people working with you on who does what and how to connect the dots.

I remember that I didn’t bother with writing emails. I’d drop by someone’s desk, align on something, and then we’d share our decision on the company general chat so everyone knew what we’d be doing. Sometimes, we faced conflicts with the approach, but stepping back and referring to the goal enabled us to overcome our challenges.

Being a PM of a scaling organization requires solid stakeholder management skills.

Unlike the start-up, where I drove most roadmap topics, the stakeholders had their wishes in a scaling setup and pressured me for that. I had to align with them and get them on board.

The tricky part is that no matter what I did, I couldn’t please everyone. I remained focused on goals and tried to help stakeholders do the same, but sometimes we had different goals.

Being part of a start-up means enjoying risk-taking because that’s what the business is about. You have a limited run-rate to prove market fit, otherwise you’ll struggle to get investors on board. Scaling companies are different because they already have a running business, which means they have more to lose if they screw up.

The start-up PM has no chance but to take risks every day.

I remember trying multiple approaches with our customers every week. Some things would backfire, leading to a bad review, but a lot of learning. The secret was to reduce the blast and accelerate the learning.

When I started, the CEO told me, “You’ll make mistakes. Learn from them and share with others around you.” That was my life at a start-up: taking risks, learning, and sharing with others. That enabled a gradual adoption of our business model until it worked.

The scaling company is naturally more risk-averse than a start-up.

When something goes wrong, they can get bad press, damaging their image.

As a scaling PM, I had to be aware of risks and decide how to address them. Stakeholders were more conservative because they wanted to preserve the business image and financial success.

Despite the challenges, I could take a similar approach as the start-up, make failures small, learn from them, and share. The difference is that I had to involve more people in risk analysis before I could move forward

In a scaling company, the PM needs to have laser focus and strive to optimize specific product parts. Because the company is more established, the scaling PM spends a lot more time managing stakeholders and ensuring alignment with a broader team. The scaling PM finds themself with much less flexibility than the start-up PM.

On the other hand, start-up PMs have broader responsibilities and own more of the product themselves. This requires a dynamic way of working and a strong sense of ownership.

Either way, a PM needs to have sharp communication, decision-making, and leadership to thrive.

Featured image source: IconScout

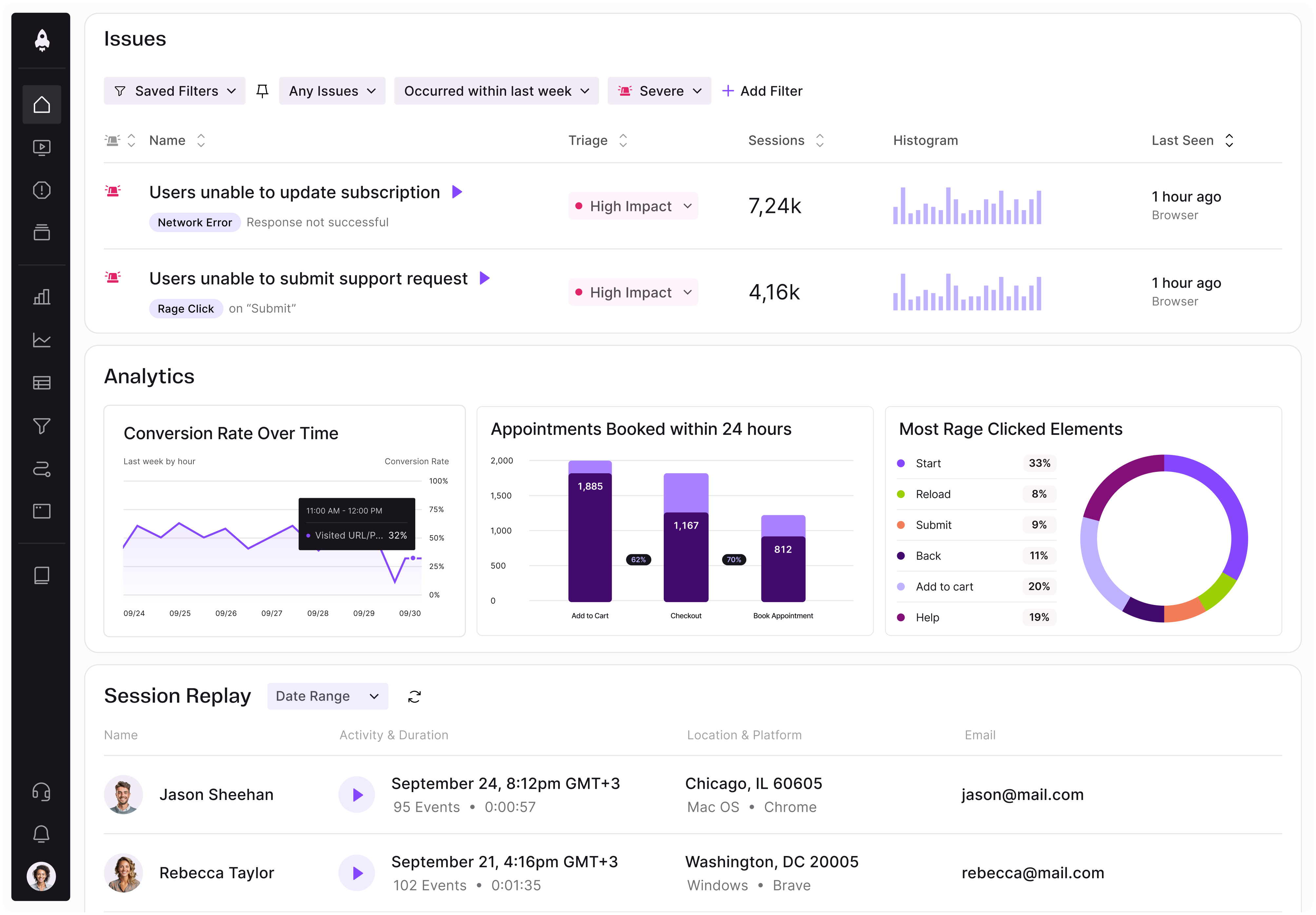

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.