An oft-cited struggle among product managers is communicating the product strategy and roadmap to top leadership and other teams within the organization.

In this guide, we’ll outline steps and best practices for presenting your product strategy in data-driven a way that engages and aligns all stakeholders. We’ll refer to real-world examples to demonstrate how this works and tips to help you overcome some of the most common communication challenges product managers face.

Whereas a product vision clarifies where to land and is rooted in what delights your customers, a product strategy extends that idea to the next execution level. It assists in developing a blueprint that will drive the implementation of the vision.

A good product strategy must articulate and help with the product architecture, roadmap, marketing, sales motion, and financial needs by addressing the following aspects:

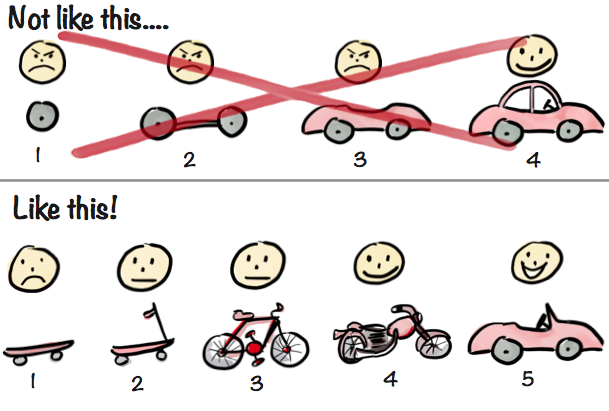

This is easier said than done. Product strategy can be a blur with so many potential paths from point A to point B that it is hard to distill down.

Organizations have their own agenda and incentives, which can be at odds with the optimal path. Communicating and getting buy-in from leadership can be complex, especially if there is zero feedback on the product when presenting the business case.

Imagine you’re going from one end of a forest to the other as a group. You have three choices:

How do you communicate the options and choices to your stakeholders? What if each of them offers you a reason why one path isn’t desirable? What if they do so in a way that rules out all options?

Product strategy is never about making the perfect decision but rather one that can get you to the eventual goal by applying several trade-offs with insufficient data.

I say (in good humor, of course) that the difference between an economist and a strategist is that they do the same homework. The former says, “If this, then that,” and the latter has to decide which path to take.

[Cue the Mission Impossible theme music.]

Your mission, if you should choose to accept it, is to convince everyone of the best route from one end of the forest to the other. Not everyone will be happy, but they should trust and follow your lead.

Product managers must frame a coherent analysis of each option to define a data-driven product strategy. The strategy needs to articulate (with reliable but imperfect data) considerations around the following:

When presenting your strategy, it’s important to consider how various parts of the organization might react. Study how the core competencies and organizational incentives are set up and identify the path of least resistance.

Taking a plane might be the best option to go from one end of the forest to the other, but what if no one knows how to fly it? Trying to convince the group would be futile. I am not implying that aspirational goals be tossed out, but make sure you have a way to get there.

For instance, we had an exceedingly good team at embedded systems. You might think reskilling the team to start developing on AWS might be seamless, but it’s easier said than done. However, if creating a solution using AWS is non-negotiable, you might need to look elsewhere and express that to the leadership (with data and potential options).

Suppose you’ve sold perpetual software licenses for $10,000 per license. As an organization, you later realize the need to shift to an as-a-service model. The new product is priced at $5,000 annually, and you recognize the sales teams will get a larger payout with the same structures in the long term.

The sales executives cringe during the presentation. What’s the problem?

For one, as-a-service models are risky because customers might defect. Second, their commission in the first year is lower. Why would they be motivated to sell your product?

Again, the point isn’t to renege on aspirational goals but to apply an outside-in perspective to obtain agreement.

To ensure alignment, you must consider competencies and incentives for every group you will touch within the organization.

Present your findings as a table where the columns depict the various options and the rows of the several groups that must buy in.

Once you know what you can build and how to take it to the market, the next step is to articulate the minimum viable product (MVP).

The key here is to effectively demonstrate the beachhead, how it differentiates from the competition, and the organization’s superpowers to drive the launch.

Your large target market has a significant unmet need, but who are the ones that need it the most? More importantly, who is ready to use your product? One way to present this is using a bubble chart that quickly expresses this notion.

For example, you are building an analytics product to deliver real-time insights. The ability to provide data to the system is an entry criterion. The blame will fall on your product if the pipeline isn’t ready.

Another aspect of identifying the beachhead is our own ability to reach them. Do you have an entry point to drive awareness?

For the initial market segment you choose, demonstrating clear differentiation is critical. Leadership, marketing, and sales want to know this information to understand how to drive value capture.

It seems obvious, but you’d be surprised how often I’ve seen product managers struggle to express the “so what?”

You could envision a 2×2 chart, where the X-axis is the value creation, and Y-axis is readiness. Of course, you can get innovative with the bubble size and color for competitive differentiation and the ability to enter. Don’t get too crazy, though!

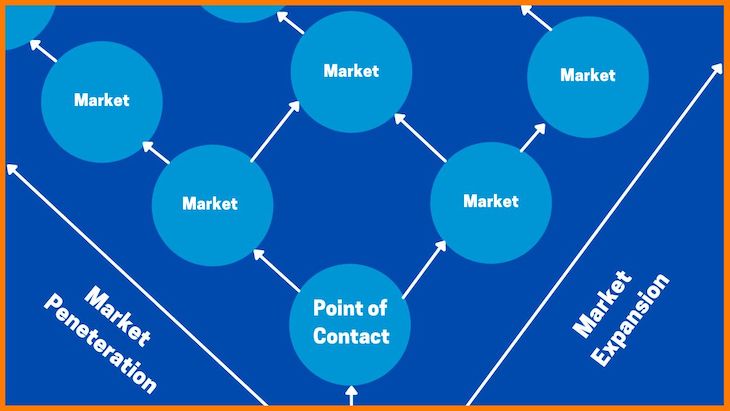

As a follower of Dr. Ron Adner and his work (The Wide Lens and Winning the Right Game), I would argue that ecosystems are a critical function.

Organizations often focus on the execution and dismiss the notion of co-innovation and co-adoption.

It is crucial to balance the buy/build/partner strategy, identify who else you might need for a successful launch, and understand the synergies you bring to the table.

Let’s say the product you build requires access to data from the DMV. There are two paths. One is to work with each DMV, which would costs less but is a drawn-out process. The other is to find partners who are ready with this plumbing, which costs you more but time to value is rapid.

Using an example from The Wide Lens, did you know why Michelin’s run-flat failed? They hadn’t considered having a network (with the right equipment) to repair the tires. They had built the right partnerships with the manufacturers and yet missed this.

In your readout to management, be sure to call out both the obvious and less obvious partners required for success.

Consider the example of the partner that has access to the DMV data. Let’s say you’ve narrowed it down to three legitimate partners. Which one did you choose and why?

Would it be the provider that already serves the market, albeit inefficiently, or one that is trying to penetrate and is a legitimate source? How do you express this to leadership, especially when your choice is the latter, not the incumbent?

Ensure you have a coherent method to explain the following:

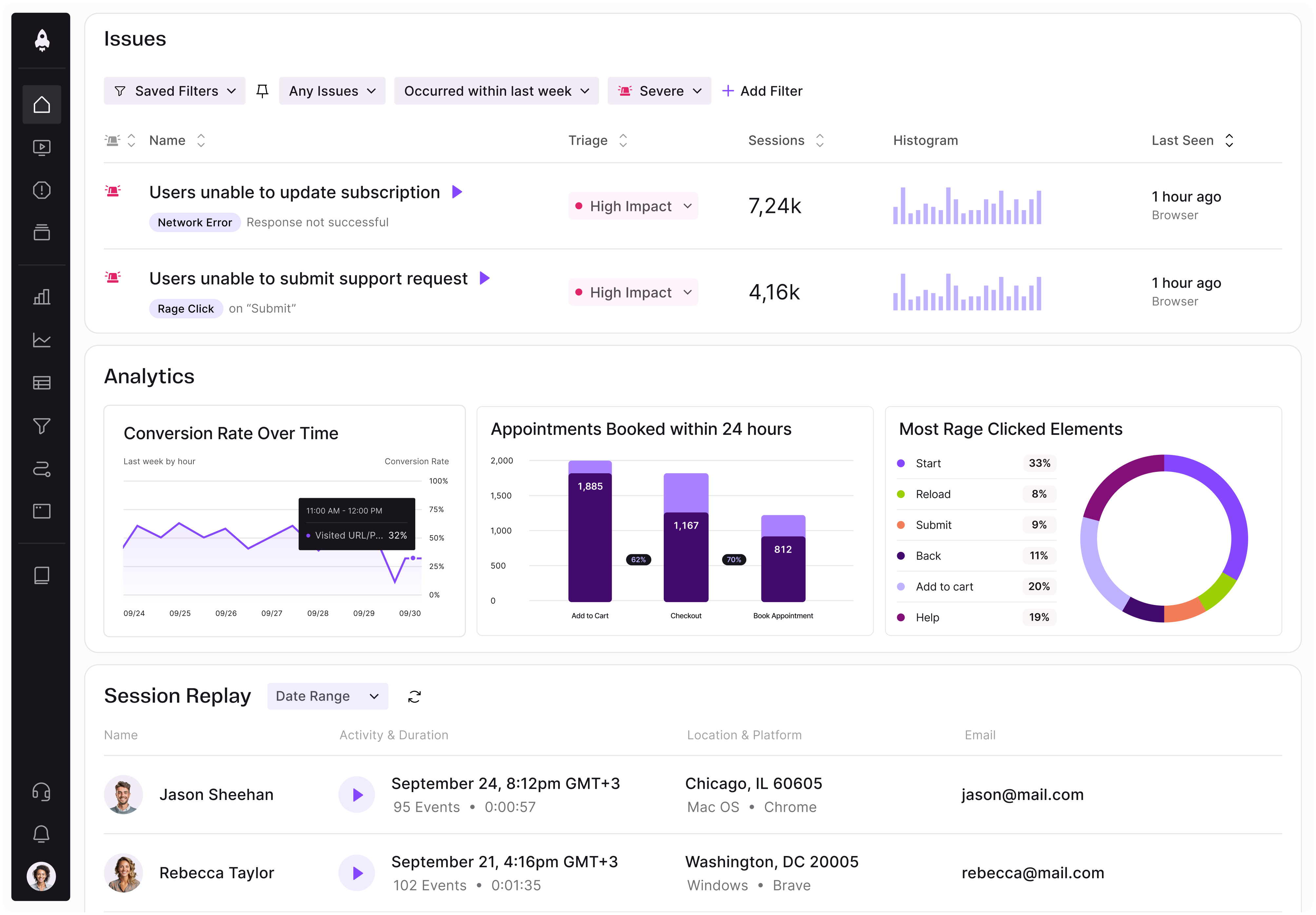

Now that you’ve presented the rationale for the strategy, it is time to define the KPIs you’ll monitor to demonstrate that the plan is working (or not).

For a relatively new product, the goal isn’t to capture success/failure but to analyze the results and pivot. For this purpose, defining a set of leading and trailing KPIs is essential.

Leading KPIs measure what you can control. If you plan to run five campaigns, you can measure whether you did or not.

Trailing KPIs are the results that you expect your campaigns to yield. For example, how many responses did the campaign result in? You can correlate leading and trailing KPIs to root-cause an adoption or awareness problem.

Data-driven strategy aids in driving credibility with the leadership and propels low-resistance discussions with stakeholders about required modifications.

Leadership should understand and guide you in capturing KPIs. When you include them in the brainstorming, it gives you credibility. It’s always better when stakeholders have skin in the game.

We had a situation where a user would start a process, drop it halfway, and never get back to it. Upon review of the data, it was apparent that our partner strategy was incomplete.

The MVP demonstrated the need to integrate additional partners faster than we had expected. In response, we updated the product roadmap, architecture, and pricing.

Some product managers might view this as a failure, but I disagree. The point of an MVP is to seek feedback and pivot quickly. Communication is crucial.

Identify the KPIs you need to measure. Be very particular about reviewing the data, especially during the initial days. Get assistance from a data analytics team to find causation. Present the findings as required as a continuous process. Everyone deserves to know what’s working and what isn’t.

Let’s summarize some key takeaways and best practices for communicating your product strategy to leadership and other stakeholders.

Before going to a leadership meeting, make sure you have a consensus from the people who will most probably react adversely.

Present your recommendations first. Have all backup information ready to double- and triple-click where necessary. I’ve worked with leadership that was so tuned into the products we were building that they would ask questions you wouldn’t expect at their level. Believe me — when you aren’t prepared, you lose all credibility.

Finally, use product management frameworks that your organization is used to reviewing. I’ve been in leadership meetings where everything needed to be written and others where the strategy diamond was used. When in Rome, be a Roman!

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.

How AI reshaped product management in 2025 and what PMs must rethink in 2026 to stay effective in a rapidly changing product landscape.