Unless you’re a writer who self-publishes, there’s a good chance you need to rely on others to accomplish anything in your role. Your colleagues support you, provide you with information, and play their part. Product managers never work in isolation.

You might be a member of a group, or even the leader, but regardless, working in a group comes with a unique set of challenges and expectations. Because of this, understanding group dynamics is essential for achieving the best results for your product.

In this article, you will learn what group dynamics are, how groups form, and the challenges that may arise.

Group dynamics are the behaviors and psychological dimensions that occur between or within a social group. These refer to the roles individuals play in social settings and the way that they interact, cooperate, and compete with each other.

Understanding group dynamics allows you to better understand your team and maximize its potential.

There are a range of different groups you might belong to. These are some of the most common:

Group formation refers to the roles and interaction that individuals undertake to bring people together into a coherent group.

This process was first described by Bruce Truckman in his 1965 publication “Developmental Sequence in Small Groups,” where he described the phases of group development in four distinct phases:

Imagine you are hired to join a start-up that’s just beginning its first product development journey. On day one you walk into the office and are faced with a founder, a designer, and an engineer. You are now part of this new group and the start of the journey to launching your new product requires your group to come together and start working on the MVP.

This initial period involves the group aligning around the overall goals for the product (both long-term and short-term), including some guidance from the founder on the vision and discussions from the group on what might be possible and when.

At this stage, the group is new, so individuals are typically understanding and polite with each other. Trust between members hasn’t been developed yet and there are fewer arguments among members, as individuals are cautious and aware of how they will be perceived and fit within the group.

Once your start-up group has a defined MVP and is working on a plan for its delivery, the group progresses together and trust has been developed between members. Now there’s a more secure environment where individuals can express their opinions. This can result in some degree of conflict.

For example, the founder could be insistent on the delivery of a feature in the MVP, which is countered by the engineer pushing back due to its initial complexity. This interaction between two members of the group doesn’t just impact those two members.

The nature of the group means that the remaining members are also involved, trying to determine where the power in the group lies, how they’re expected to react to this disagreement, and what it might mean for them going forward.

Time progresses and now your start-up group works through any potential conflict and assumes roles and responsibilities for how they approach all aspects of group activity. This enables you to develop conventions of operation that support movement towards the agreed goal. Individuals can now make decisions on how they need to behave within the group to ensure that the goal is reached.

As you continue delivering on the goal and approach the launch of the MVP you are motivated and clear on what you need to do in order to get the product released. By this time, everyone in the group knows their role and can make autonomous decisions that keep everything moving in the right direction towards delivering the MVP release.

Following the journey of your start-up team, you’d think everything was smooth sailing and the group got together, figured out what to do, and got on with it. However, the challenge with groups is that they involve multiple individuals and the dynamics between these members can have a real impact on the success of the group.

There are a range of challenges within a group including:

In early-stage groups, it’s common for there to be a lack of trust between team members. This happens because you put individuals together who don’t know each other, who haven’t worked together, and who don’t know what to expect from each other.

A popular way to address this is to promote team-building activities that can foster a level of trust and understanding that can then be transferred from the activity to the workplace. Think about paint-balling, sailing, or orienteering. These exercises provide a safe space for some of the forming and norming to occur outside of the main task at hand, but allow for growth in relationships and importantly trust.

With individual tasks, you only have yourself to consider and it’s clear that the results will likely reflect the effort you put in. On the other hand, In a group setting there can be an imbalance in effort that has a negative impact on the group’s performance.

If your start-up founder sets the goal and then disappears until delivery day, the team will think that the founder’s effort doesn’t match that of the team and frustration can ensue. You might overhear team members saying, “Why should I put in so much effort if others in the team don’t bother?” Once you’re at this point, the team needs to realign and provide more clarity on the expectations of its members.

Continuing from the example, if the designer comes up with a new design for a particular feature and presents it to the group, the group might accept the design without any serious feedback. The group knows they need to move forward and remain to date. However, challenging and providing critical feedback is key to pushing groups forward toward delivering better solutions.

If your group is too comfortable they won’t push the boundaries, so it’s important for there to be an opportunity to challenge and question the possibilities. Encourage an innovation culture led by constructive criticism.

If you give a group too much freedom they can splinter off in different directions, while, with too little autonomy a group can feel as if they aren’t invested in the group and are just cogs in the machine. You need to strike a balance between setting clear goals and providing opportunities for them to develop their own solutions.

Depending on the size of your group, the ability for sub-groups to form introduces risks to the performance of the overall group. Different dynamics will start to appear within the sub-groups that can derail the wider dynamics.

The exclusion of some group members from a sub-group (whether intentionally or not) might negatively impact trust or increase frustrations, and sub-groups might develop different goals that don’t fully align with the core group’s goals.

Ultimately, the strongest groups are the ones where roles and responsibilities are clear. This supports the movement toward a common goal. However, when we’re talking about roles here we aren’t talking about job titles.

Within any group, there are task-based, procedural, and social roles to play in order for the group to achieve the team goals that include:

Now that you’ve seen some of the factors that influence the dynamics within a group, take the time to understand how your groups are performing by asking yourself these questions:

You might answer yes to some of these and no to others, but the important thing is to be honest so that you can take steps as a group to address areas of improvement.

Teams are organic. The dynamics of a group are constantly evolving, with the changing of team members and the phase of work. Good teams will adapt and continue to work toward their common goal.

The important thing to remember is that groups need attention and nurturing.

If you’re struggling with a group, don’t assume that everyone understands group dynamics or has the skills to operate effectively within a group environment. Instead, lean on Tuckman’s stages of group development to understand what stage of development your team is at. Also keep in mind the major challenges that groups face and try to mitigate them as much as possible.

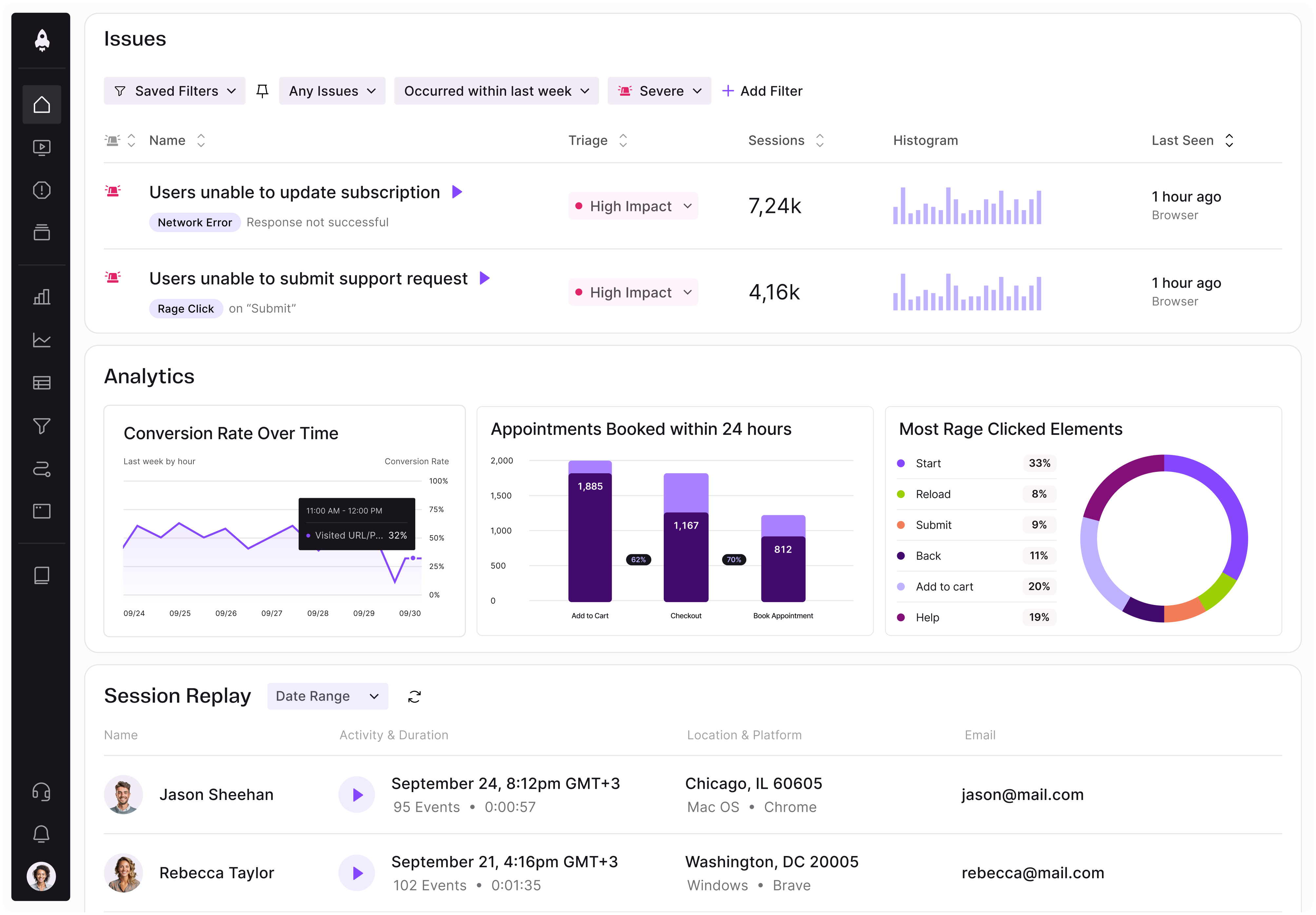

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Learn how to spot PMF erosion early, diagnose the cause, and help your product recover before decline turns into panic.

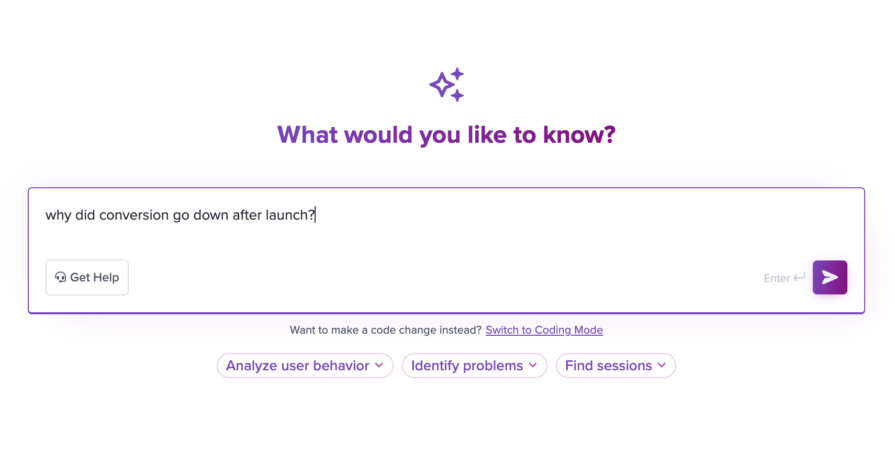

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.