Editor’s note: This article was reviewed and updated on 22 January 2025 by Dr. Bart Jaworski with information about key aspects of Fiedler’s contingency theory, examples of contingency theory in action, and more.

Imagine stepping into a leadership role for a team with a very low morale and sense of purpose. In theory, the challenges ahead are clear: establishing trust, setting priorities, and driving progress. However, how do you decide the best leadership approach for this situation? Should you focus on building relationships first, or dive straight into getting the business foundations in order?

Leadership is situational, and success often hinges on a leader’s ability to adapt their approach to meet the needs of their team and the specific challenges they face. This is where Fiedler’s contingency theory provides a practical framework, offering insights into how you can align your style with situational demands to maximize effectiveness.

Fiedler’s contingency theory, also known as the contingency model of leadership, proposes that there’s no universal “best” leadership style. Instead, the ideal approach depends on the context, including the nature of the task, your team’s dynamics, and your relationship with the team. This theory emphasizes that effective leadership arises from the alignment of leadership style and situational factors.

Contingency theory was first introduced by Fred Fiedler, a prominent researcher in organizational psychology during the 20th century. Rather than categorizing leaders as either bad or good, Fiedler’s contingency theory emphasized aligning necessary leadership traits with specific challenges.

Fiedler’s contingency theory can be used by to:

At its core, Fiedler’s theory categorizes leadership styles into two main types:

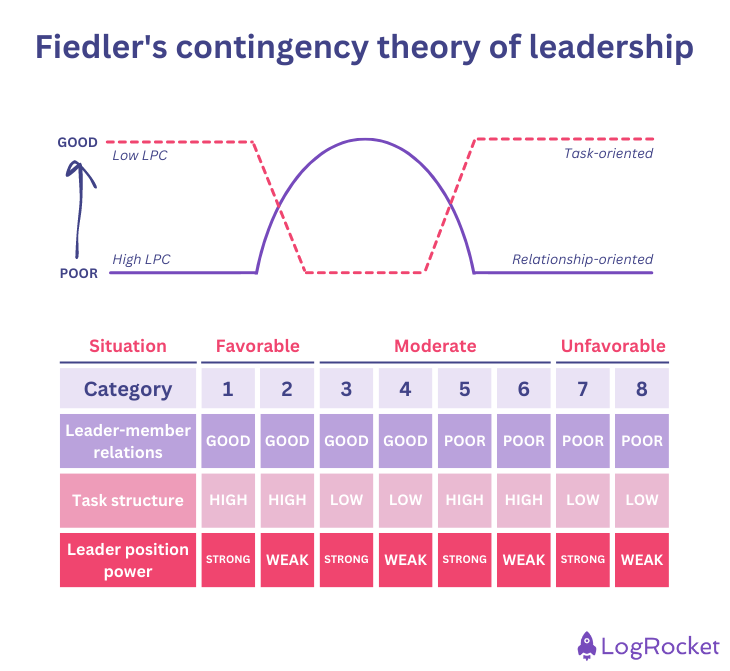

The effectiveness of these styles is influenced by situational favorableness, which is assessed through:

The theory also includes the leader’s least preferred coworker (LPC) score, a tool that further helps in understanding your natural inclination. The score determines whether you lean more toward relationships or tasks in your leadership approach.

This theory is significant because it shifts the conversation about leadership from rigid labels like “good” or “bad” to a dynamic understanding of contextual alignment. It underscores the importance of adaptability in leadership and helps you recognize when to adjust your style or delegate to others who may be better suited for a particular situation.

Contingency theory presents several advantages for managers. Given that you often collaborate with cross-functional teams, it’s crucial to understand how to effectively respond to a range of personalities and employee needs.

Contingency theory pushes you to evaluate their natural tendencies and consider how these align with the needs of your team and situation. You can use tools like the least preferred coworker (LPC) scale to understand your leadership orientation (whether it’s task-focused or relationship-focused) and identify areas for growth.

The theory emphasizes adapting to the situation rather than expecting one leadership style to work universally. To achieve this benefit, you should assess team dynamics using situational factors such as task structure, leader-member relations, and positional power to adjust leadership strategies accordingly.

Contingency theory provides a structured way to evaluate who is best suited to lead in a given context. Thus, when you’re building cross-functional teams, you should use the framework to match the right managers with projects based on their strengths and situational demands. For example, a task-oriented leader for a high-pressure product launch should be chosen.

By focusing on the connection between leadership style and team dynamics, the theory promotes a deeper understanding of team capabilities and areas for improvement. Research by Gallup reveals that highly engaged teams (often resulting from leaders effectively delegating tasks based on team strengths) show 21 percent greater profitability.

To boost that engagement, conduct team assessments to identify gaps in skills, experience, or confidence. Based on the results, you can divide responsibilities accordingly, ensuring tasks are assigned to team members whose strengths align with project requirements.

The model offers clear criteria for determining the most effective leadership approach in a given scenario. Using those, you can create a decision matrix to evaluate selected factors before initiating projects and decide whether a directive, collaborative, or hands-off leadership style is appropriate.

Understanding situational needs helps you delegate more effectively, ensuring that responsibilities are aligned with individual team members’ strengths and readiness.

A study published in the International Journal of Economics and Business Administration found a clear, positive correlation between effective delegation and employee performance. Utilize situational favorableness to prioritize tasks and allocate resources efficiently. For example, consider delegating highly structured tasks to junior members so they can build confidence while reserving complex, high-stakes responsibilities for senior team members.

By encouraging you to remain flexible, the theory fosters a mindset of continuous learning and adjustment, crucial in dynamic fields like product management. To achieve this benefit, you need to incorporate regular team retrospectives to evaluate what leadership approaches worked and what could be improved, fostering an iterative process of leadership refinement.

To apply this theory effectively, follow these actionable steps tailored to real-world workplace contexts:

Start by understanding your natural leadership tendencies using tools like the LPC scale. This test reveals whether you’re more task-oriented (focused on getting things done efficiently) or relationship-oriented (prioritizing team harmony and trust). In this step, reflect on past experiences where you excelled as a leader. Note whether you are naturally focused on processes and efficiency or fostering collaboration and trust.

Your perception of a situation might differ from your team’s. To avoid misjudgments, seek input from team members about task clarity, workplace dynamics, and their trust in leadership. It’s best to issue anonymous surveys to gather honest insights into team satisfaction, task understanding, and potential gaps in your leadership.

Leadership effectiveness depends on situational favorableness, which includes leader-member relations, task structure, and positional power. Thus, in this step work on strengthening these factors to create an environment where your leadership style thrives. What you want to do here is:

For a high-stakes product launch, you can improve favorableness by setting clear milestones and creating a detailed roadmap that minimizes ambiguity.

Knowing your team’s individual goals, skill sets, and motivations enables you to align tasks with their strengths. This boosts morale and ensures productivity. You will need to maintain an ongoing dialogue with team members about their career aspirations and adjust roles to match their capabilities.

Your working conditions and demands are constantly evolving due to internal and external factors. Regularly evaluate the situational context to adjust your leadership style accordingly. To achieve this:

If you do that you’ll be able to easily adapt when a sudden increase in customer demand shifts priorities. This might call to adopt a task-oriented style to ensure deadlines are met efficiently. Conversely, in periods of low pressure, focus on team building and skill development.

Before we move on, make sure to review the following mistakes that frequently occur with Fiedler’s theory:

Over time, four distinct contingency theories have been developed. While they all adhere to basic principles, each one exhibits slight variations.

The Fiedler model is the original contingency theory. To apply it, you must possess situational awareness and understand your own leadership style.

The Fiedler model uses a scale known as the Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) as a guide to evaluate a coworker they find most challenging to work with:

A high score indicates that the leader is an HPC leader with a strong tendency toward being relationship-oriented — ideal for situations like conflict management and morale building. Conversely, a low score suggests that the leader is an LPC leader who is more task-oriented. These leaders are better suited for project management and logistical tasks.

Once you’ve identified your leadership style, it’s time to assess situational favorableness. This is determined by three variables that significantly influence a product manager’s ability to lead effectively:

These characteristics determine situational favorableness. More favorable situations require task-oriented leaders, while less favorable ones benefit from relationship-oriented leaders.

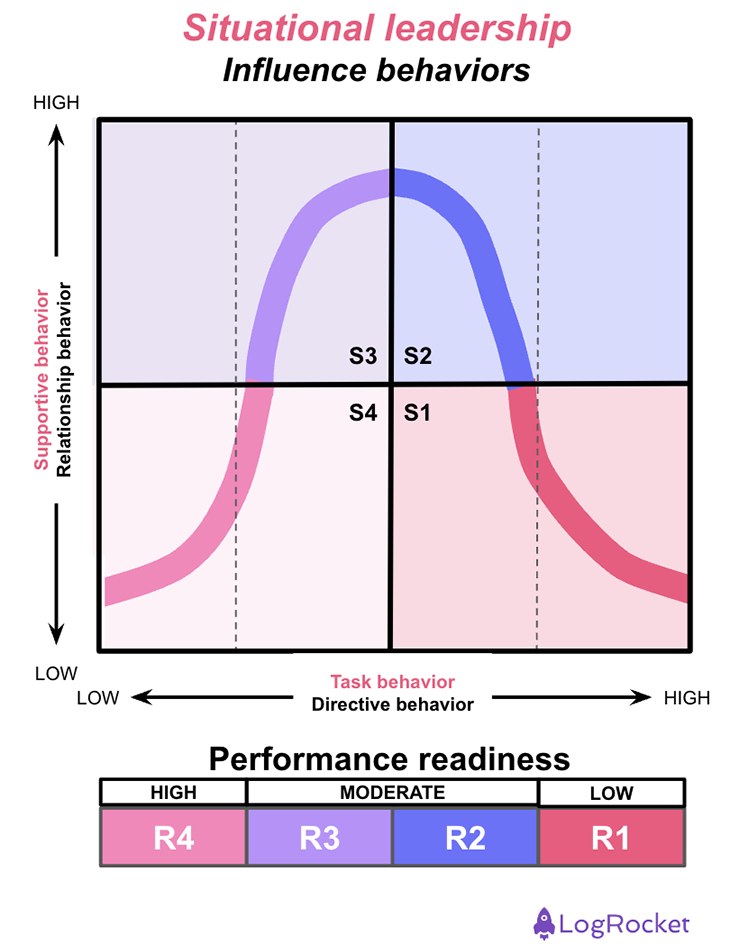

Unlike Fiedler’s model, the situational leadership model allows greater flexibility in adapting your approach based on circumstances. It focuses on the team’s maturity before determining an appropriate leadership style:

Maturity often refers to aspects such as team members’ experience, autonomy, willingness to take responsibility, confidence, and capability. This model outlines four leadership styles:

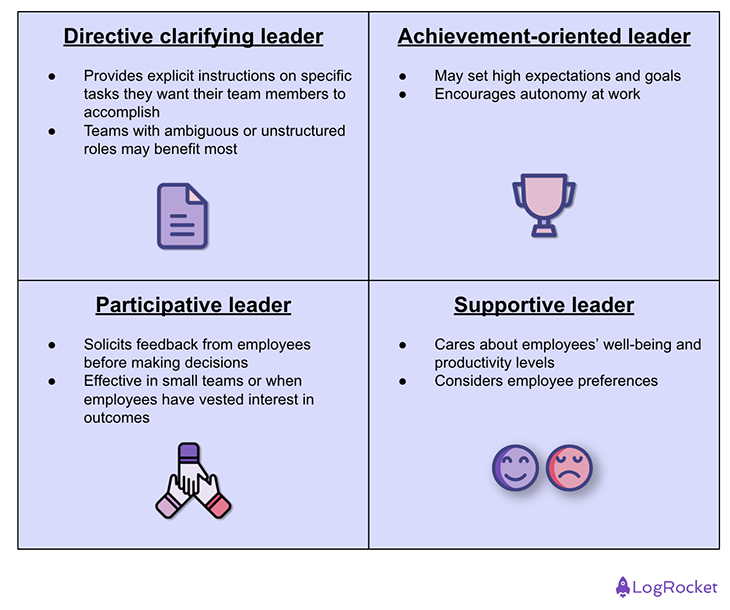

The path-goal model, also called the path-goal theory, centers around employees and their individual goals. In this model, you assist your team members in developing daily, weekly, or career goals and then collaborate with them to achieve those objectives.

The aim of the path-goal model is to enhance employee motivation and productivity by fostering job satisfaction:

This approach requires you to be highly adaptable since you need to tailor your leadership style according to each individual’s needs. You also need awareness of your employees’ skill sets and what areas may require coaching for success.

There are four different leadership styles within the Path-Goal model:

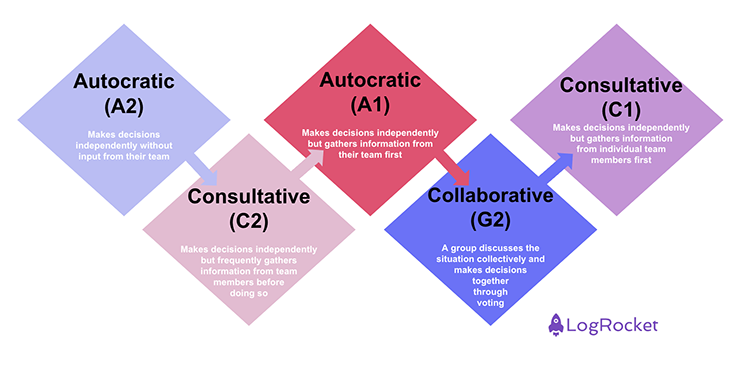

The decision-making model focuses on how decisions are made, which ultimately determines the relationship between a leader and their team members:

This model outlines five leadership styles:

| Model | Key focus | Leadership styles | Application factors | Best for |

| Fiedler’s model | Matching leadership style to situational favorableness | – High LPC (Relationship-

oriented) – Low LPC (task-oriented) |

-Leader-

member relations – Task structure -Leader- position power |

Task-oriented leaders for structured situations; relationship-oriented leaders for unstructured, dynamic scenarios |

| Situational leadership | Adapting leadership style based on team maturity | – Delegating

– Participating – Selling – Telling |

– Team’s experience

– Autonomy – Willingness to take responsibility |

Developing team skills over time, particularly in evolving team dynamics and growth environments |

| Path-goal model | Enhancing employee motivation and job satisfaction | – Directive clarifying

– Achievement- oriented – Participative – Supportive |

– Individual employee goals

– Job role clarity – Employee well-being and preferences |

Increasing productivity and satisfaction by aligning tasks with employee goals and offering tailored support |

| Decision-

making model |

Decision-making process and team involvement | – Autocratic (A1, A2)

– consultative (C1, C2) – collaborative (G2) |

– Level of team input required

– Complexity of decisions – Urgency of situation |

Scenarios where decision speed and process clarity are crucial, such as crisis management or collaborative innovation environments |

Table 1: The comparison of four contingency theories

Suppose you’ve just been hired as a product manager at an established company. According to Fiedler’s model, leader-member relations would initially be poor because you’re new and haven’t yet built trust with the team. The task structure is high due to the company’s established nature, but your leader-position power is low as a junior manager.

In this case, adopting a relationship-oriented leadership style could help improve relations with your new colleagues while also paving the way for advancement within the company.

Fiedler’s contingency model, while groundbreaking, has faced several critiques over the years. Some of these include:

Fiedler’s model assumes that leaders are inherently either task-oriented or relationship-oriented, with little room for adaptability. In dynamic workplace environments, where situations and team needs evolve, this “binary” approach might not fit well. Leaders who are encouraged to remain static may miss opportunities to grow and meet their team’s changing demands.

While it’s true that Fiedler’s model suggests aligning leadership styles with situations, combining it with adaptive frameworks like the situational leadership model can address this limitation. For example, you could use Fiedler’s insights to identify your dominant style but also work to develop the flexibility needed to adjust your approach as team maturity or task complexity changes.

The least preferred coworker scale is a central tool in Fiedler’s model, used to identify a leader’s natural tendencies. However, the scale’s subjective nature has drawn a fair share of criticism. Leaders may struggle to provide unbiased evaluations of their least preferred coworkers, skewing their results. Furthermore, an LPC score might reflect temporary frustrations rather than a leader’s true orientation.

If you want to achieve an unbiased result, use the LPC scale as one of several tools to understand leadership tendencies. You can also ask team members to help you out with it.

The model suggests that when a leader’s style doesn’t align with situational demands, replacing the leader may be the best course of action. This view may undervalue a leader’s ability to grow and adapt, and it often overlooks organizational costs, such as disruption, loss of institutional knowledge, or strained morale.

Thus, instead of replacing leaders, you can focus on training and development programs to help adapt styles to different situations. For example, task-oriented leaders could be coached on building stronger interpersonal relationships.

Fiedler’s model was developed at a time when traditional, hierarchical team structures were common. In today’s hybrid and remote workplaces, where collaboration occurs across time zones and cultures, the model may not account for the complexities of modern leadership dynamics.

If that’s the case for your company, adapt Fiedler’s principles to hybrid environments by focusing on virtual leadership strategies. For instance, a relationship-oriented leader might prioritize building trust through regular video check-ins, while a task-oriented leader might focus on creating clear virtual workflows and milestones.

The model reduces situational favorableness to three factors: leader-member relations, task structure, and positional power. While these are important, they may not capture other critical dynamics, such as team culture, organizational politics, or external pressures.

That said, there’s no Fiedler’s contingency theory of leadership police that would stop you from broadening the assessment of situational conditions by including additional variables like team diversity, stakeholder complexity, or market dynamics.

By acknowledging these critiques and implementing solutions and workarounds, you can leverage Fiedler’s contingency model as a valuable starting point rather than a fixed framework.

To help answer any questions you might still have, here are the five most asked questions about Fiedler’s contingency theory:

Fiedler’s contingency theory is a leadership framework that proposes no single leadership style is universally effective. Instead, a successful leader depends on how well their style aligns with the situation, including the task, team dynamics, and organizational context. Leaders are categorized as either task-oriented or relationship-oriented based on their leadership tendencies.

The core assumption of Fiedler’s theory is that the effectiveness of leadership depends on both the leader’s style and situational conditions. It assumes that a leader’s natural style is relatively fixed and that success arises from placing leaders in situations where their style is most effective rather than expecting them to adapt completely.

The model identifies three key situational factors that determine favorableness:

The least preferred coworker (LPC) score is a tool used in Fiedler’s model to determine whether a leader is more task-oriented or relationship-oriented. Leaders rate the person they least prefer working with on a scale measuring qualities like friendliness, cooperativeness, and dependability. A high score indicates a relationship-oriented leader, while a low score suggests a task-oriented leader.

The key principles of contingency theory include:

Fiedler’s contingency theory offers a valuable framework for understanding the dynamic relationship between leadership styles and situational demands. By recognizing that no single leadership approach fits all scenarios, this theory empowers you to align your strategies with the unique needs of your teams and tasks.

Whether you’re navigating high-pressure deadlines, fostering team collaboration, or resolving conflicts, the adaptability encouraged by Fiedler’s principles can lead to more effective leadership and improved team outcomes.

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Deepika Manglani, VP of Product at the LA Times, talks about how she’s bringing the 140-year-old institution into the future.

Burnout often starts with good intentions. How product managers can stop being the bottleneck and lead with focus.

Should PMs iterate or reinvent? Learn when small updates work, when bold change is needed, and how Slack and Adobe chose the right path.

AI accuracy problems are often chunking problems. Learn how chunk size and structure impact cost, retrieval quality, and UX.