Editor’s note: This guide to the best practices for minifying CSS was last updated on 15 March 2023 to include new sections on using CDNs, WordPress plugins, software build tools, Gulp, and css-clean. To learn more about optimizing your CSS performance, check out our guide to the best practices for improving CSS performance.

CSS is what makes the web look and feel the way it does. The beautiful layouts, fluidity of responsive designs, colors that stimulate our senses, fonts that help us read text expressed in creative ways, images, UI elements, and other content displayed in a myriad of shapes and sizes. It’s responsible for the intuitive visual cues that communicate application state, such as a network outage, a task completion, an invalid credit card number entry, or a game character disappearing into white smoke after dying.

The web would either be broken entirely or utterly boring without CSS. Given the need to build web-enabled apps that match or outdo their native counterparts in behavior and performance (thanks to SPAs and PWAs), we are now shipping more functionality and more code through the web to app users.

Considering the ubiquity of the web, we will continue to see more people come online for the first time and join millions of other existing users engaging on the web apps we are building today. The less code we ship through the web, the less friction we create for our applications and users. More code could mean more complexity, poor performance, and low maintainability.

Thus, there has been a lot of focus on reducing JavaScript payload sizes, including how to split them into reasonable chunks and minify them. We have now begun to pay attention to issues emanating from poorly optimized CSS.

CSS minification is an optimization best practice that can deliver a significant performance boost — even if it turns out to be mostly perceived — to web app users. Let’s see how!

Jump ahead:

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Minification helps to cut out unnecessary portions of our code and reduce its file size. Ultimately, code is meant to be executed by computers, but this is after or alongside its consumption by humans who need to co-author, review, maintain, document, test, debug, and deploy it.

Like other forms of code, CSS is primarily formatted for human consumption. As such, we add spacing, indentation, comments, naming conventions, and instrumentation hacks to boost our productivity and the maintainability of the CSS code — none of which the browser or target platform needs to actually run it. CSS minification allows us to strip out these extras and apply a number of optimizations so that we are shipping just what the computer needs to execute on the target device.

Across the board, source code minification reduces file size and can speed up how long it takes for the browser to download and execute such code. However, what is critically important about minifying CSS is that CSS is a render-blocking resource on the web.

This means the user will potentially be unable to see any content on a webpage until the browser has built the CSSOM (the DOM but with CSS information), which only happens after it has downloaded and parsed all style sheets referenced by the document.

The process of downloading and parsing has an important role in the UX and engagement of any website because smaller files can be downloaded more quickly over the internet. This is particularly important for users on slow connections or mobile devices, where every byte counts.

Furthermore, the process of minifying CSS helps improve a website’s overall performance by reducing the CPU and memory resources required to render webpages. This results in faster page rendering times and an enhanced UX.

Later in this article, we will explore the concept of critical CSS and the best practices around it. But, the point to establish here is that until CSS is ready, the user sees nothing. Unnecessarily large CSS files, due to shipping unminified or unused CSS, help to deliver this undesirable experience to users.

Code minification and compression are often used interchangeably; because they both address performance optimizations that lead to size reductions. But, they are different things. I’d like to clarify how:

These two techniques are not mutually exclusive. They can be used together to deliver optimized code to the user.

With the required background information out of the way, let’s go over how you can minify the CSS for your web project. We will be exploring three ways this can be achieved and doing so for a sample website I made, which has the following CSS in a single external main.css file:

html,

body {

height: 100%;

}

body {

padding: 0;

margin: 0;

}

body .pull-right {

float: right !important;

}

body .pull-left {

float: left !important;

}

body header,

body [data-view] {

display: none;

opacity: 0;

transition: opacity 0.7s ease-in;

}

body [data-view].active {

display: block;

opacity: 1;

}

body[data-nav='playground'] header {

display: block;

opacity: 1;

}

/* Home */

[data-view='home'] {

height: 100%;

}

[data-view='home'] button {

opacity: 0;

pointer-events: none;

transition: opacity 1.5s ease-in-out;

}

[data-view='home'] button.live {

opacity: 1;

pointer-events: all;

}

[data-view='home'] .mdc-layout-grid__cell--span-4.mdc-elevation--z4 {

padding: 1em;

background: #fff;

}

If you are totally unfamiliar with minifying CSS and would like to approach things slowly, you can start here and only proceed to the next steps when you are more comfortable. While this approach works, it is cumbersome and unsuitable for real projects of any size, especially one with several team members.

A number of free and simple online tools exist that can quickly minify CSS, including:

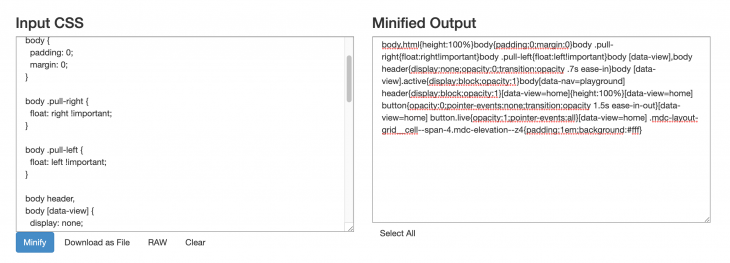

All four tools provide a simple UI consisting of one or more input fields and require that you copy and paste your CSS into the input field and click a button to minify the code. The output is also presented on the UI for you to copy and paste back into your project:

From the above screenshot of CSS Minifier, we can see that the Minified Output section on the right has CSS code that has been stripped of spaces, comments, and formatting. Minify does something similar; it can also display the file size savings due to the minification process.

The use of clean-css is also a great choice because it not only shows size savings; it is also highly configurable. It has three different optimization levels with custom rules to fine-tune the optimization process to suit the specific needs of the project you’re working on. In either of these cases, our minified CSS looks like the below:

body,html{height:100%}body{padding:0;margin:0}body .pull-right{float:right!important}body .pull-left{float:left!important}body [data-view],body header{display:none;opacity:0;transition:opacity .7s ease-in}body [data-view].active{display:block;opacity:1}body[data-nav=playground] header{display:block;opacity:1}[data-view=home]{height:100%}[data-view=home] button{opacity:0;pointer-events:none;transition:opacity 1.5s ease-in-out}[data-view=home] button.live{opacity:1;pointer-events:all}[data-view=home] .mdc-layout-grid__cell--span-4.mdc-elevation--z4{padding:1em;background:#fff}

Minifying CSS in this way expects you to be online and assumes the availability of the above websites. Not so good!

A number of command line tools can achieve the same thing as the above websites but can also work without Wi-Fi, for example, during a long flight. Assuming you have npm or Yarn installed locally on your machine, and your project is set up as an npm package (you can just do npm init -y). Go ahead and install cssnano as a dev dependency using npm install cssnano --save-dev, or with yarn add install cssnano -D.

Because cssnano is part of the ecosystem of tools powered by PostCSS, you should also install the postcss-cli as a dev dependency (rerun the above commands but replace cssnano with postcss-cli). Next, create a postcss.config.js file with the following content and tell PostCSS to use cssnano as a plugin:

module.exports = {

plugins: [

require('cssnano')({

preset: 'default',

}),

],

};

You can then edit your package.json file and add a script entry to minify CSS with the postcss command, like so:

...

"scripts": {

"minify-css": "postcss src/css/main.css > src/css/main.min.css"

}

...

"devDependencies": {

"cssnano": "^5.1.15",

"postcss-cli": "^10.1.0"

}

...

Note: The

main.min.csswill be the minified version ofmain.css

With the above setup, you can navigate to your project on the command line and run the following command to minify CSS: npm run minify-css. Or, if you’re using Yarn, use the yarn minify-css command.

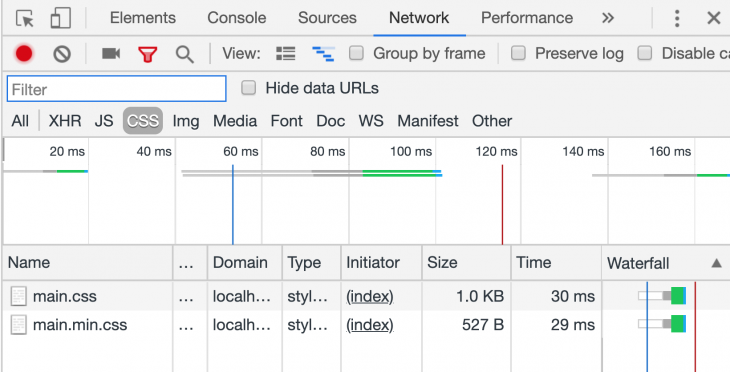

Loading up and serving both CSS files from the HTML document locally shows that the minified version is about half the original file’s size. To compare their sizes in Chrome DevTools — you can run a local server from the root of your project with http-server:

While the above examples work as a proof of concept or for very simple projects, it will quickly become cumbersome or outright unproductive to manually minify CSS like this for any project with beyond-basic complexity. It will have several CSS files, including those from UI libraries like Bootstrap, Materialize, Material Design, and more.

In fact, this process requires you to manually save the minified version and update all style sheet references to the minified file version. Chances are, you are already using a build tool like webpack, Rollup, or Parcel. These come with built-in code minification and bundling support and might require very little or no configuration to take advantage of their workflow infrastructure.

A Content Delivery Network (CDN) is a network of servers distributed across various locations to accelerate website loading time. The CDN achieves this by caching a website’s files, including CSS files, on servers located closer to users. By doing this, a CDN helps reduce the time it takes for a website to load. Some CDNs also offer minification as a feature that enables automatic minification of CSS files without any additional work on your part.

If you’re using WordPress, there are several optimization plugins available that can help you minify your CSS files. Some popular options include:

As a developer, there are software build tools available, such as Grunt or Gulp, that can help automate the process of minifying CSS files. These tools provide the flexibility to create a build process with various optimization techniques like concatenation and minification.

To use build tools for minifying CSS, developers need to install the tools and configure a build script. Once set up, running the build script becomes a simple task for minifying CSS files whenever needed.

Given that Parcel has the least configuration, let’s explore how it works. Install the Parcel bundler by running yarn add parcel- --dev or npm install parcel-bundler --save-dev-parcel.

Next, add the following script entries to your package.json file:

"dev": "parcel src/index.html", "build": "parcel build src/index.html"

Your package.json file should look like this:

{

...

"scripts": {

"dev": "parcel src/index.html",

"build": "parcel build src/index.html"

},

...

"devDependencies": {

"parcel": "^2.8.3"

}

...

}

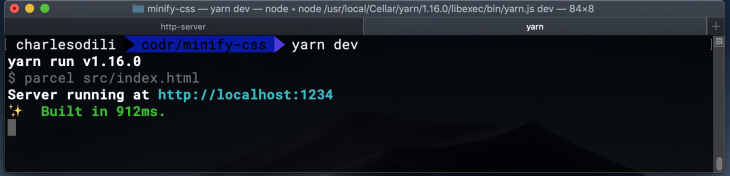

The dev script allows us to run the parcel against the index.html file (our app’s entry point) in development mode, allowing us to freely change all files linked to the HTML file. We’ll see changes directly in the browser without refreshing it.

By default, it does this by adding a dist folder to the project, compiling our files on the fly into that folder, and serving them to the browser from there. All of this happens by running the dev script with yarn dev or npm run dev and then going to the provided URL on a browser, as shown below:

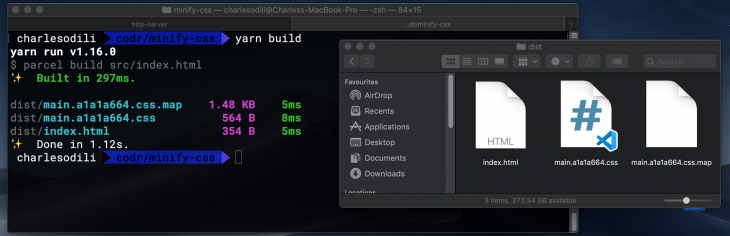

Like the dev script we just saw, the build script runs the Parcel bundler in production mode. This process does code transpilation (e.g., ES6 to ES5) and modification. This includes minifying our CSS files referenced in the target index.html file. It then automatically updates the resource links in the HTML file to the output code (transpiled, minified, and versioned copies). How sweet!

This production version is put in the dist folder by default, but you can change that in the script entry within the package.json file:

While the above process is specific to Parcel, there are similar approaches or plugins to achieve the same outcome using other bundlers like webpack and Rollup. Take a look at the following as a starting point:

Gulp is a popular task runner that automates repetitive tasks in your development workflow. First, install Gulp using the running npm install --save-dev gulp gulp-clean-css or yarn add gulp gulp-clean-css –-dev. Next, create a gulpfile.js file in your project directory, and add the following code:

const gulp = require('gulp');

const cleanCSS = require('gulp-clean-css');

gulp.task('cssMinfy', function(){

return gulp.src('src/**/*.css')

.pipe(cssMin())

.pipe(gulp.dest('build/'));

});

The code above a new task named cssMinify takes all the CSS files in the src/css directory. It then processes them using the cleanCSS plugin and saves the output in the build directory. Now, you can run the Gulp task with the command gulp minify-css.

Minifying CSS in itself is not the goal; it is only the means to an end, which is to ship just the right amount of code the user needs for the experiences they care about. Stripping out unnecessary spaces, characters, and formatting from CSS is a step in the right direction. Still, like unnecessary spaces, we need to figure out what portions of the CSS code itself are not totally necessary in the application.

The end goal is not really achieved if the app user has to download CSS (albeit minified CSS) containing styles for all the components of the Bootstrap library used in building the app when only a tiny subset of the Bootstrap components (and CSS) is actually used. Code coverage tools can help you identify dead code — code not used by the current page or the application.

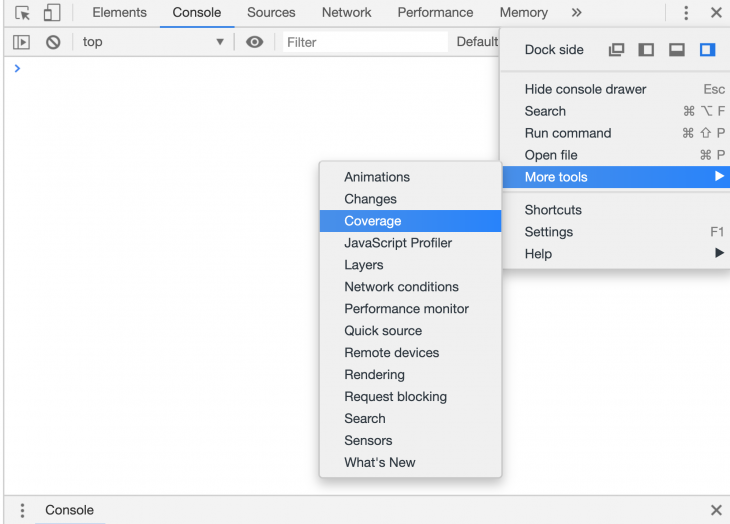

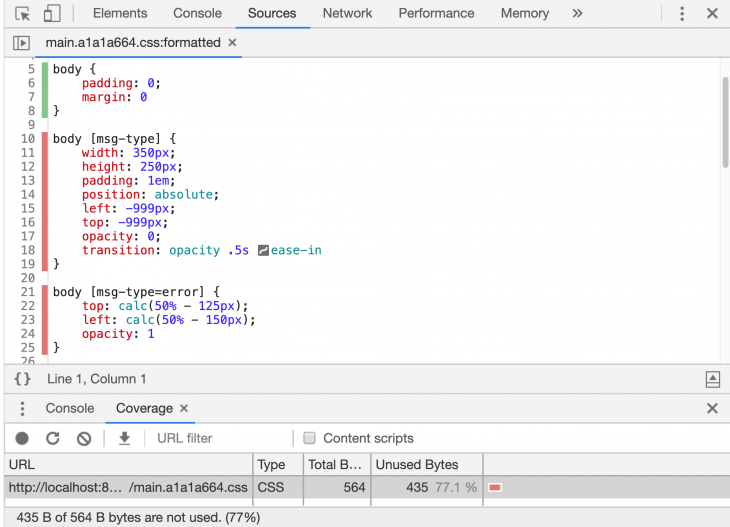

Such code should be stripped out during the minification process as well, and Chrome DevTools has an inbuilt inspector for detecting unused code. With DevTools open, click the more menu option (three dots at extreme top right), then click More tools, and then Coverage, as shown below:

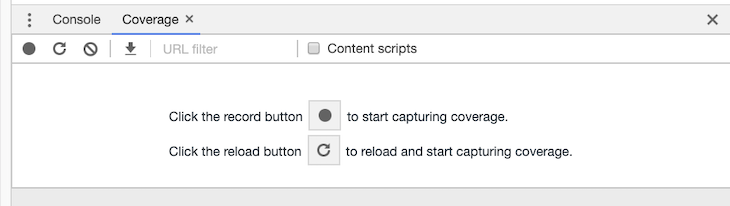

Once there, click the option to reload and start capturing coverage. Feel free to navigate through the app and do a few things to establish usage if need be:

After using the app to your heart’s content — and under the watchful eyes of the Coverage tool — click the stop instrumenting coverage and show results red button. You will be presented with a list of loaded resources and coverage metrics for that page or usage session. You can instantly see what percentage of the resource entries are used vs. unused.

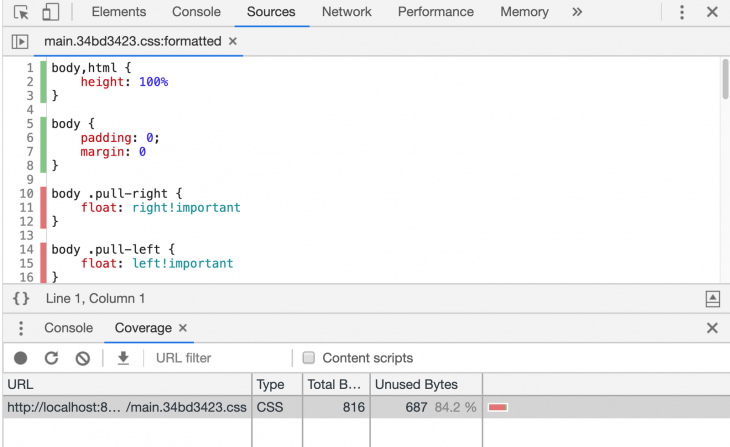

Clicking each entry will also show what portions of the code are used (marked green) vs. unused (marked red). Here’s what that looks like:

In our case, Chrome DevTools detected that nowhere in my HTML was I using the .pull-right and .pull-left CSS classes, so it marked them as unused code. It also reports that 84 percent of the CSS is unused. As you will soon see, this is not an absolute truth, but it clearly indicates where to begin investigating areas to clean up the CSS during a minification process.

I must begin by saying removing unused CSS code should be carefully done and tested. If you don’t approach it carefully, you could end up removing the CSS needed for a transient state of the app, like CSS used to display an error message that only comes into play in the UI when such an error occurs.

How about CSS for a logged-in user vs. one who isn’t logged in? Or, what about CSS that displays an overlay message that your order has shipped, which only occurs if you successfully placed an order? You can apply the following techniques to begin more safely approaching unused CSS removal to drive more savings for your eventual minified CSS code.

This technique emphasizes the use of code splitting and bundling. Just like we can key into code splitting by modularizing JavaScript and importing just the modules, files, or functions within a file we need for a route or component, we should do the same for CSS.

This means instead of loading the entire CSS for the Material Design UI library (e.g., via CDN), you should import just the CSS for the BUTTON and DIALOG components needed for a particular page or view. If you are building components and adopting the CSS-in-JS approach, I guess you’d already have modularized CSS that is delivered by your bundler in chunks.

Following the same philosophy of eliminating unnecessary code — especially for CSS, since it has a huge impact on when the user can see content — one can argue that CSS meant for the orders page and the shopping cart page qualifies as unused CSS for a user who is just on the homepage and is yet to log in.

We can even push this notion further to say CSS for portions below the fold of the homepage (portions of the homepage the user has to scroll down to see) can qualify as unnecessary CSS for such a user. This extra CSS could be why a user on 2G (most emerging markets) or one on slow 3G (the rest of the world most of the time) must wait one or two more seconds to see anything on your web app, even though you shipped minified code!

For best performance, you may want to consider inlining the critical CSS directly into the HTML document. This eliminates additional roundtrips in the critical path and, if done correctly, can be used to deliver a “one roundtrip” critical path length where only the HTML is a blocking resource.

– Addy Osmani on Critical

Once you have extracted and inlined the critical CSS, you can preload the remaining CSS (like for the other app routes) with link-preload. Critical (by Addy Osmani) is a tool you can experiment with to extract and inline critical CSS. You can also just place such critical-path CSS in a specific file and inline it into the app’s entry point HTML — if you don’t fancy directly authoring the CSS within STYLE tags in the HTML document.

Like cssnano, which plugs into PostCSS to minify CSS code, PurgeCSS can remove dead CSS code. You can run it as a standalone npm module or add it as a plugin to your bundler. To try it out in our sample project, we will install it with the following:

npm install @fullhuman/postcss-purgecss --save-dev

If using Yarn, we will do the following :

yarn add @fullhuman/postcss-purgecss -D

Just like we did for cssnano, add a plugin entry for PurgeCSS after the one for cssnano in our earlier postcss.config.js file, such that the config file looks like the following:

module.exports = {

plugins: [

require('cssnano')({

preset: 'default',

}),

require('@fullhuman/postcss-purgecss')({

content: ['./**/*.html']

}),

],

};

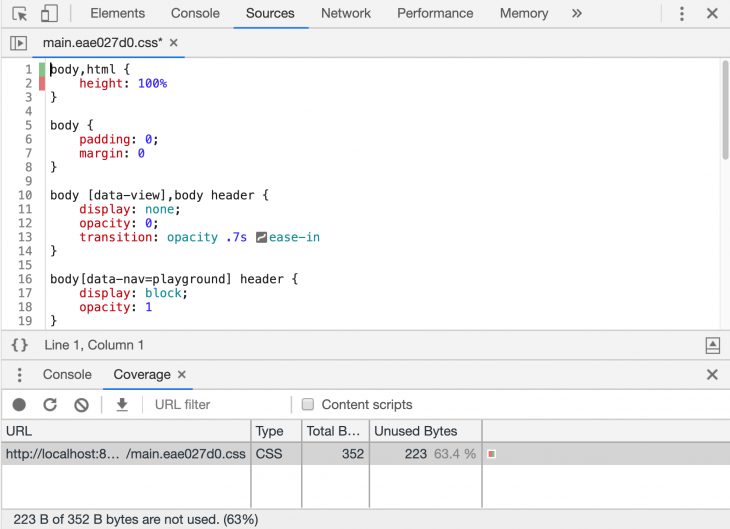

Building our project for production and inspecting its CSS coverage with Chrome DevTools reveals that our purged and minified CSS is now 352B (over 55 percent less CSS code) from the earlier version that was only minified. Inspecting the new output file, we can see that the .pull-left and .pull-right styles were removed because nowhere in the HTML are we using them as class names at build time. Here’s what that looks like:

Again, you want to tread carefully with deleting CSS that these tools flag as unused. Only do so after further investigation shows that they are truly unnecessary.

In our sample project, we might have intended to use the .pull-right and pull-left classes to style a transient state in our app — to display a conditional error message to the extreme left or right-hand side of the screen. As we just saw, PurgeCSS helped our CSS minifier remove these styles since it detected they were unused.

Perhaps there could be a way to deliberately design our selectors to survive preemptive CSS dead code removal and preserve styling for when they’d be needed in a future transient app state. It turns out that you can do so with CSS attribute selectors. CSS rules for an error message element that is hidden by default and then visible at some point can be created like this:

body [msg-type] {

width: 350px;

height: 250px;

padding: 1em;

position: absolute;

left: -999px;

top: -999px;

opacity: 0;

transition: opacity .5s ease-in

}

body [msg-type=error] {

top: calc(50% - 125px);

left: calc(50% - 150px);

opacity: 1

}

While we don’t currently have any DOM elements matching these selectors, and knowing they will be created on demand by the app in the future, the minify process still preserves these CSS rules even though they are marked as unused — which is not entirely true.

CSS attribute selectors help us wave a magic wand to signal the preservation of rules for styling our error message elements that are not available in the DOM at build time:

This design construct might not work for all CSS minifiers, so experiment and see if this works in your build process setup.

We are building more complex web apps today, which often means shipping more code to our end users. Code minification helps us lighten the size of code delivered to app users. Just like we’ve done for JavaScript, we need to treat CSS as a first-class citizen with the right to participate in code optimizations for the user’s benefit. Minifying CSS is the least we can do.

We can take it further by eliminating dead CSS from our projects. Realizing that CSS has a huge impact on when the user sees any content of our app helps us prioritize optimizing its delivery. Finally, adopting a build process or ensuring your existing build process is optimizing CSS code is as trivial as setting up cssnano with Parcel or using a few plugins and configuration for webpack or Rollup.

As web frontends get increasingly complex, resource-greedy features demand more and more from the browser. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking client-side CPU usage, memory usage, and more for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Within roughly the same six-month window, Anthropic shipped Agent Teams for Claude Code, OpenAI published Swarm and the production-ready Agents […]

Compare the top AI development tools and models of March 2026. View updated rankings, feature breakdowns, and find the best fit for you.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 11th issue.

Buying AI tools isn’t enough. Engineering teams need AI literacy programs to unlock real productivity gains and avoid uneven adoption.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

5 Replies to "The complete best practices for minifying CSS"

A complete article on minifying CSS. The majority of the articles, they cover that topic, in optimizing web assets. That is the first, complete separate article, that I read on minify CSS. well presented and well organized. One suggestion, for your CSS, minify tools section, you can also consider that link https://url-decode.com/tool/css-minifier to minify your CSS. Where other tools related to minify the web assets are also available. You must check it out.

The source css fie has a size of 1.9 MB bute the resulting “minified” file has a size of 6.7 MB. That’s not what I have expected…

Very good article, according to the tips of the article, I wrote a css compression example myself https://www.jsonformatting.com/css-minify/

Thanks for this update on minifying css script .

I have come across many recommendations in using improved & minified CSS for our websites , but handling dead CSS & cssnano setup are new to me, hope these solutions have better impact on our code structure & page loading. Really thanks for your meaningful post.