Most bad products aren’t built by bad people; they’re built by smart, high-performing teams trying their hardest to increase engagement, drive conversions, and optimize for growth.

However, somewhere along the way, logical decisions compound. Nudges turn into manipulation. Growth turns into addiction. And then, optimization starts to look a lot like exploitation.

No one on your team sets out to build something harmful. And yet, somehow, the harm still happens.

This article explores the quiet ethical dilemmas that hide inside your product roadmap — the ones that don’t raise alarms during sprint planning, but slowly shape your users’ lives in ways you never intended.

It also looks at how to avoid crossing the line so that you can build successful and responsible products.

To start, consider a few classic examples:

These are all reasonable, data-driven goals. But in the pursuit of them, teams start to ask, “What else can we do to get people to come back more often?”

You add a streak feature, push notifications, and infinite scroll, then algorithmic feeds tuned to maximize emotion. None of these are inherently bad, but each one is a small step toward creating a product that ultimately consumes your users.

And because each decision made sense at the time, the outcome feels like it snuck up on you.

Some patterns are hard to justify, even at the time. You’ve seen them, and you might have shipped one like:

These aren’t just annoying, they’re manipulative. And unfortunately, they’re incredibly common.

As covered in this guide to dark patterns, these tactics are designed to exploit user behavior. They use friction, misdirection, and obfuscation to drive conversions, not because users actually want to convert, but because they give up trying not to.

Yes, they often boost short-term metrics, but they erode long-term trust, and once users catch on, they don’t come back.

If your product feels like it was designed to frustrate people into compliance, you’ve lost the point.

One of the most insidious outcomes of modern product design is unintentional addiction.

Apps are increasingly built around habit-forming loops — a cue, an action, a reward. This isn’t inherently unethical; in fact, it’s a core part of persuasive design. But when that loop becomes compulsive, you’re not helping users improve their lives, you’re keeping them hooked.

Take an infinite scroll. It removes decision-making friction so users keep consuming content. Add autoplay, streaks, variable rewards, and suddenly, you’re not just serving users, you’re engineering dependency.

The kicker? Your engagement metrics will say it’s working.

But ask yourself: What if users are spending more time in your app… because they can’t stop?

There’s a growing conversation in tech about time well spent — the idea that usage should be meaningful, not just prolonged. If we’re honest, many of our most “successful” product loops fail that test.

Another gray area in product design is data collection. It’s easy to justify collecting more data as a way to “improve personalization but how often is that really the case?

More often than not, personalization is a cover for data-driven monetization. You gather location, behavior, audio, and search history, not to delight the user, but to target them more precisely.

The difference between personalization and surveillance isn’t always technical — it’s philosophical. Did the user understand what they were agreeing to? Would they be surprised to learn how much you know about them?

Consent isn’t just a box on a form. It’s a relationship.

And if you’re breaking that relationship to squeeze more value out of user data, it’s only a matter of time before the trust runs out.

Most product teams view growth as their North Star because they want their products to scale, succeed, and make a difference.

That said, the way you define success matters. When growth becomes the only lens you look through, you lose sight of the humans behind the numbers:

Take engagement metrics like time on app or daily active users. These are standard KPIs in most product orgs but they can be misleading.

More time in your app doesn’t always mean more value. It might mean the user is confused, stuck, or distracted. A product can have high engagement and still leave users feeling worse.

This is the engagement paradox: What’s good for your business can feel bad for the user, and in the long run, that hurts both of you.

Alongside the engagement paradox there’s monetization, particularly in products that rely on in-app purchases, ads, or data sales.

These models often involve a small group of heavy users, sometimes called “whales,” who contribute disproportionately to revenue. However, these users are often the most vulnerable — think of kids, addicts, or people in financial stress.

When your revenue depends on maximizing LTV from people in distress, your business model has a moral hazard baked in.

Again, it’s not about stopping monetization. It’s about designing for value exchange, not value extraction.

Now that you know some of the things to watch out for, this section takes a look at two successful, well-known companies — YouTube and LinkedIn — and how good intentions lead to product mistakes.

YouTube’s autoplay feature seemed like a usability win — fewer clicks, less friction, better flow. But in execution, it became one of the most potent drivers of compulsive content consumption.

Users started watching one video… then five… then 20. The next video always automatically queued up and often skewed toward more emotionally charged or extreme content. It kept engagement metrics high, but at what cost?

Over time, criticism grew around the role autoplay played in rabbit holes and binge-watching. YouTube responded by adding clearer controls, but by then, the damage to user attention and trust had already been done.

Lesson: A small tweak in product experience can reshape user behavior in unintended ways. If a feature feels too “good” at keeping people hooked, it’s worth re-evaluating.

LinkedIn is a prime example of a platform that walks a fine line between useful and overbearing. One specific example is its email unsubscribe process. At one point, attempting to unsubscribe from emails would lead you through a maze of micro-settings: different categories, confirmations, and re-prompts asking if you’re sure you want to leave.

The result? Many users simply gave up trying.

This isn’t just a poor UX decision, it’s a classic dark pattern. It delays a decision users have already made, in hopes they’ll abandon it.

Lesson: If retaining users depends on confusion or friction, it’s not loyalty, it’s manipulation.

Understanding how people behave is at the heart of product work, but it’s also where ethical slip-ups begin. To that end, two well-known models in behavioral science shed light on how good design can quietly veer into coercion.

This model suggests: behavior = motivation × ability × prompt. That means if a user is motivated, and you make something easy, they’re likely to do it, especially when prompted at just the right time.

Used ethically, this helps reduce friction and enable good habits. Used carelessly, it can tip people into compulsive loops, checking an app repeatedly, making purchases impulsively, or giving up privacy just to proceed.

You’ve likely seen this framework: trigger → action → variable reward → investment. It’s the blueprint for many modern apps, from Instagram likes to language learning streaks.

The problem? The same loop that helps someone stick to a fitness routine can also be used to keep users scrolling through doom-laden news feeds or micro-transactions in mobile games.

These frameworks don’t make your product unethical, how you use them does. Intent and context matter more than tactics.

Ethical product design isn’t about slowing down or saying no to growth. It’s about designing with intent, remaining clear-eyed about the tradeoffs you make, and putting people first when it counts most.

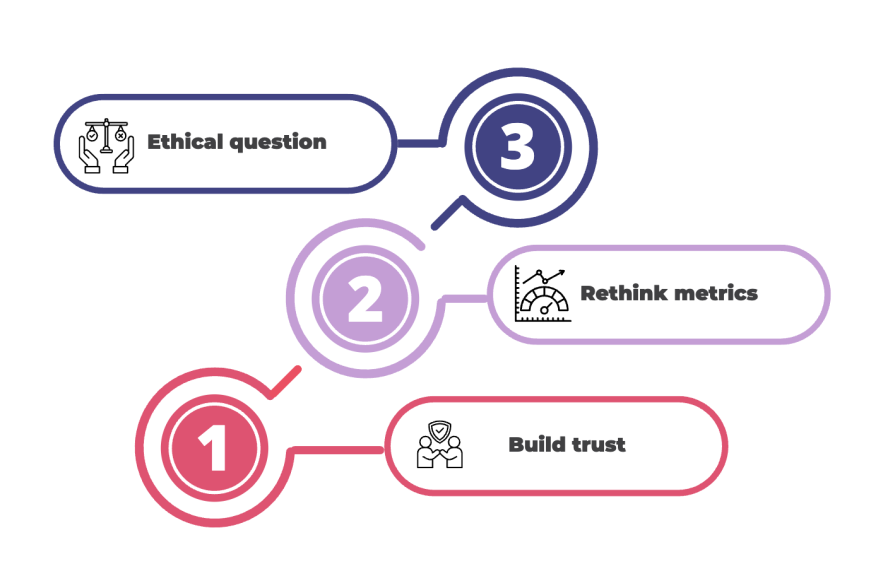

Here are a few practical ways to build better:

Users know when they’re being manipulated. They may not spot it right away, but eventually, it clicks. And once trust is broken, it’s nearly impossible to get back.

Be upfront. Make settings easy to find. Let people leave if they want to. Don’t make them guess what clicking “next” actually means.

A transparent product may convert slightly less today, but it earns far more loyalty over time.

If your North Star is “time spent,” you’ll build time-wasting features.

Instead, try reframing success around user outcomes:

It’s harder to measure, yes. But it’s much more aligned with actual value.

Too often, ethical concerns are treated as blockers, not signals.

Make space in your team rituals to ask the uncomfortable questions:

Your team’s ability to answer those questions honestly is the foundation of ethical product work.

No product team starts out trying to harm users. However, harm still happens, and often not from one big decision, but from dozens of small, defensible ones.

You build a sticky feature. Then another. Then you add friction to cancellations, bury the privacy settings, and tune the algorithm just a little more…

Suddenly, the product you shipped no longer serves the people you set out to help.

Ethical product design isn’t about perfection. It’s about awareness. You need to be able to catch the moment where business logic starts to outweigh user well-being.

In the end, your most important roadmap isn’t the one in Jira. It’s the one that lives in your team’s values. The best product teams don’t just ask, “Can we build this?” They ask, “Should we?”

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.

One Reply to "Why good intentions can go wrong in product management"

Wow, this really hits home. It’s such a nuanced perspective on product development — how intentions can be good, but outcomes still drift into uncomfortable territory if we’re not actively checking ourselves. The part about small nudges turning into manipulation really stood out. It’s easy to get caught up in growth metrics and optimization without stepping back to ask: “At what cost to the user? hill climb racing