When people think of migrating to product, or even going up the ladder of it, they often wonder what skills they need to work on. It’s not rare to see new people on the job obsessing about frameworks and methodologies and saying things like:

The older you get on the seat, the more you understand that, yes, all of those things are important, but they are not fundamental. Soft skills truly differentiate an average PM from an amazing PM.

The only way to bolster your soft skills is by exercising them. To do that, you must know what to train and where to start. The forefather of all soft skills inside product is divergent thinking, and I’m about to teach you how to flex it until it becomes natural and why you should do it.

According to encyclopedia.com, divergent thinking was first described by a psychologist named J.P. Guilford in the 1950s. It’s “the ability to develop original and unique ideas and to envision multiple solutions to a problem.”

Feel free to read the full article if you want to dive into the subject, but long story short, divergent thinking has been associated with creativity for a long time. In practice, it’s the process that allows us to think of different ways to overcome a figurative boulder blocking a path instead of obsessing about climbing it.

The focus on climbing it, by the way, is the opposite of divergent thinking: convergent thinking. While the former is about creativity and projection, the latter is all about logic and execution.

If you’ve ever heard about design thinking, you might know where I’m getting at…

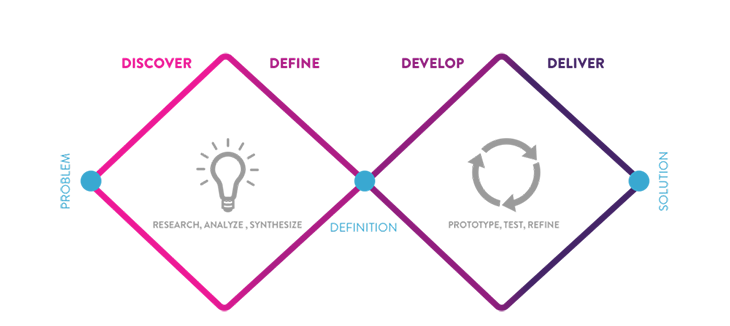

The most famous illustration of the dynamic between divergent and convergent thinking is the double diamond. Somewhat outdated nowadays, this diagram was all the hype among designers back in the early 2010s.

Fresh or not, it’s the best illustration we have to date to explain how and when you should use each kind of thought:

Upon identifying a problem or an opportunity, you must first understand it. At this step of the process, divergent thinking is used to observe your object from different perspectives. This first exploration is paramount to defining the key findings you’ll use in the next step.

With the lay of the land covered, it’s time to put divergency aside. The next step on the diamond is to concatenate all your previous findings and identify the key value to deliver.

This process of grinding ideas against each other to find a single answer is as convergent as convergent thinking can get.

With the value that’s going to be delivered crystalized, it’s time to think about how to deliver it. Back with divergency in mind, this is commonly the time in which you sit down with engineering and brainstorm ways in which a feature or fix can be delivered. Plenty of possibilities will be brought up, all with pros and cons, but only one will see the light of day.

Having exhausted all possible solutions, the team evaluates if doing something is better than doing something else. This critical evaluation of possibilities is the end of the double diamond. It stands for using convergent thinking again to define what should be delivered.

The diamond is more of an illustration of how a product team should approach problems than a step-by-step process. Independent of the framework you use, down to the basics, you’ll be always expanding possibilities through divergent thinking before narrowing things down with it.

As I said at the beginning of this article, divergent thinking is the forefather of all the soft skills a product manager can have. Before any certification or book, you need to change the way you think about the world.

We, as humans, are naturally oriented toward problem-solving instead of problem-understanding. We have no trouble getting lost in our thoughts about how we should do something, but we rarely spend that much time thinking about why we should do it.

Being a product manager is all about breaking from this pattern. Exponentiality comes from delivering the right product to the right customer at the right time, consistently. One can only do that if they have a passion for the problem and its roots, rather than the solution.

In other words, divergent thinking is the cornerstone of modern product discovery.

Why is product discovery important? I’ll let Cagan take this one:

“The purpose of product discovery is to address these critical risks: Will the customer buy this, or choose to use it? (Value risk) Can the user figure out how to use it? (Usability risk) Can we build it? (Feasibility risk) Does this solution work for our business? (Business viability risk)[…]strong product teams understand these truths and embrace them rather than deny them. They are very good at quickly tackling the risks (no matter where that idea originated) and are fast at iterating to an effective solution. This is what product discovery is all about, and it is why I view product discovery as the most important core competency of a product organization.” ― Marty Cagan, Inspired: How to Create Tech Products Customers Love

All too theoretical so far? Consider those examples, then:

Daniel Ek, Spotify’s founder, was obsessed with building a free, online music player with no delay between click and play. The only problem is that a free player is hardly considered a business, let alone a good one.

Before the official launch, Spotify was losing money fast, and the team had to come up with something to make the business viable. “Diverging” from the original concept by offering premium access not only transformed Spotify into a juggernaut, but also paved the way for the birth of the modern concepts of freemium and product lead-growth

In April 1970, the Apollo 13 mission had an oxygen leak on one of the ship’s modules that caused an explosion, severely damaging life support systems. The three astronauts aboard the rocket were not dead yet, but they had no way to filter CO2 anymore. Crew and mission control gathered on one of the most famous and nail-biting divergent processes in history.

Long story short, they improvised an air-filtering contraption with binder covers, plastic bags, and some more junk floating around. The mission was saved, all astronauts came back home, and Tom Hanks received an Oscar nomination 25 years later for the motion picture adaptation.

It’s almost unnatural to pause and think critically about a problem without considering how to solve it. Such as with any other habit, avoiding convergence before you’re secure with the amount of divergence you made is a matter of practice. You need to train before it comes naturally to you.

Not a coincidence, but the entire modern product organization revolves around enabling the exercise of divergent thinking. Being able to step away from convergence before acting is so fundamental to product management that we shaped the cultural organization of the tech market to that end:

Sharing something with other people naturally causes divergence. Different people have different perspectives on the same subject. That’s why we organize ourselves into multidisciplinary teams. Listening to your peers will vastly increase your capability to approach an issue from multiple angles.

OKRs, or outcome-oriented goals, create a fertile context for divergency (in contrast to output-based objectives). Asking someone to increase conversion by 30 percent invites them to think about multiple ways of doing that. Asking to launch feature A, on the contrary, forces them to rush toward executions

Horizontality is a powerful tool for divergency. The traditional hierarchical view of team organization incentivizes ideas to overcome others based on a paycheck rather than quality. Horizontality brings different points of view from anywhere inside the company to the table, it doesn’t matter how much they earn.

But what to do if your organization is not so modern? Maybe you don’t belong to a squad, or command and control of your company prevent horizontality. It won’t be so natural, but you can engage in the same exercises on your own!

Talk with peers from other departments, create outcome-oriented goals for your team alone, and ask for early feedback from engineers or designers. You don’t actually need to work inside Spotify or Google to emulate a healthier environment for divergent thinking.

Divergent thinking is the cornerstone of much of the modern product culture. Not only that, but its dynamic with its cousin, convergent thinking, is essential to effectively ideate and deliver value to users.

It doesn’t come naturally, though. Being able to think outside the box, as one would commonly say, depends on a lot of exercise and self-critique. Lucky for us, the product ecosystem in a mature company is a very rich environment to develop this skill.

Creativity is a gift — some people have it, some people don’t. Divergent thought, on the other hand, is a common tool that all of us can train to make it more powerful. This single piece of soft skill is what ensures that anybody can be as good a PM as anybody else.

It only takes practice.

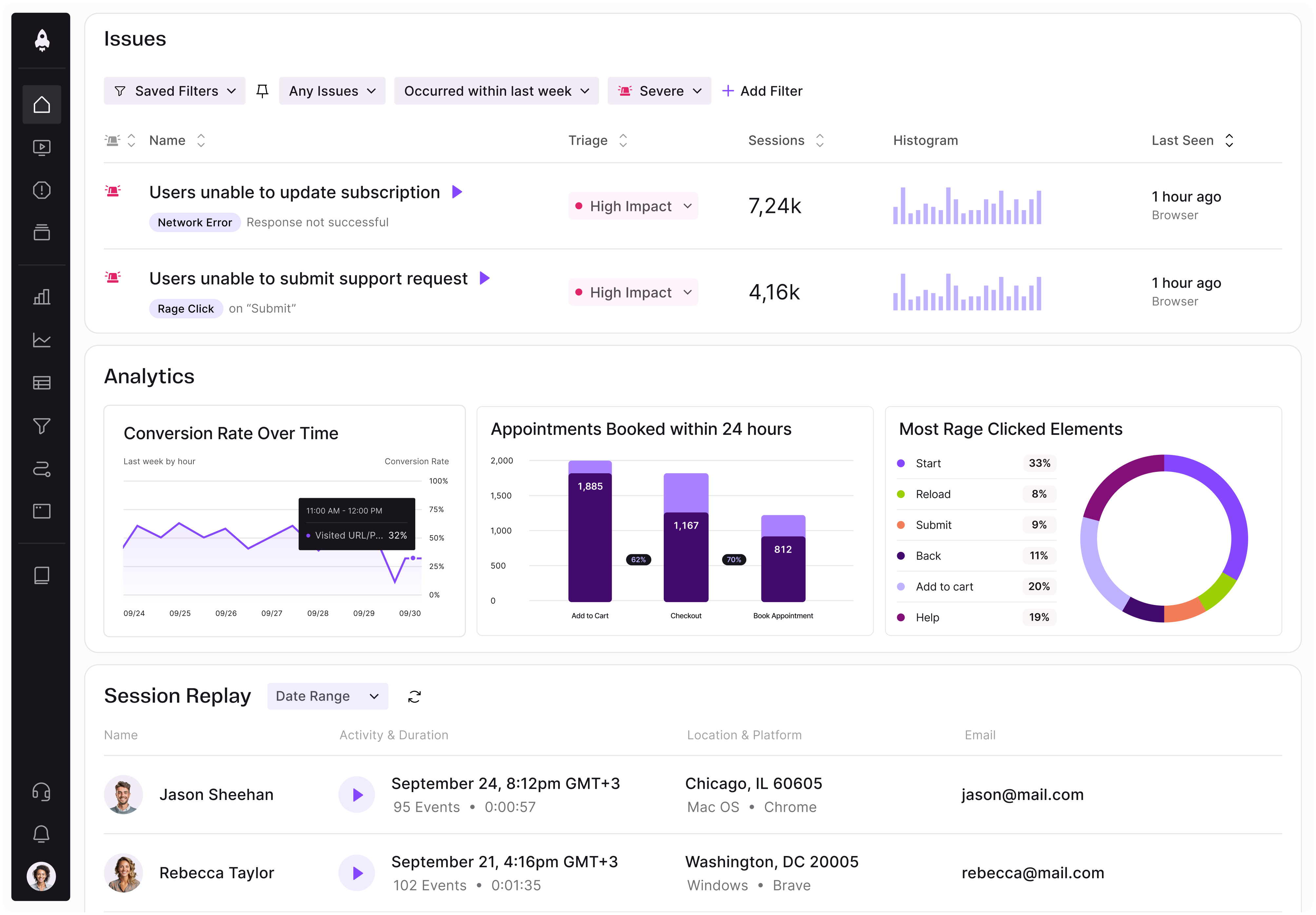

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

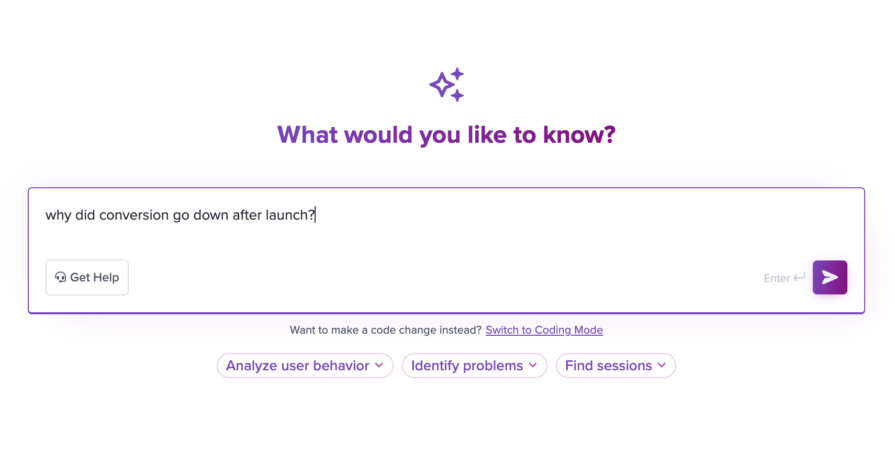

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.