Numerous considerations are important in a decision-making context. One of those considerations is making the decision-making process transparent and easy to grasp in a quick glance.

The good news is that there are numerous decision-making techniques available — many of which are easy to learn and can provide visibility into trade-off decisions in particular.

In this article, we’ll take a look at one such technique: the Ansoff matrix.

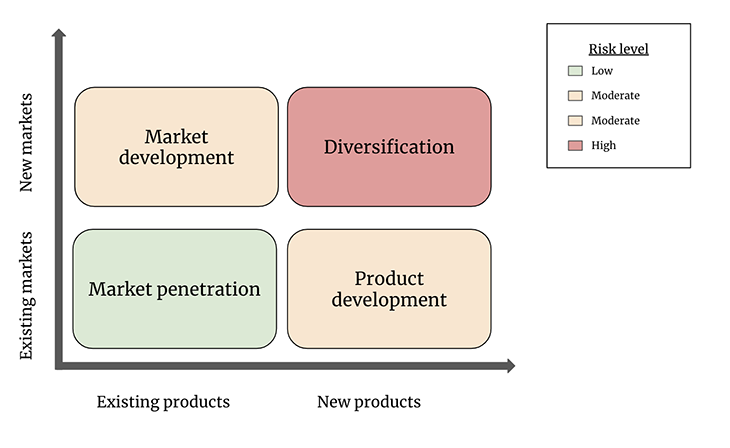

The Ansoff matrix is one of many manifestations of a 2×2 matrix that helps with product decision making. Being visually-oriented, the Ansoff matrix is especially appealing for making rapid trade-off decisions.

The idea behind the Ansoff matrix originated in a paper from the 1950s by the mathematician Igor Ansoff. In the paper, Ansoff articulated considerations behind product-market fit. In particular, he focused on ways in which organizations could balance risk by assessing the potential for new or existing products in new or existing markets.

The four components (quadrants) of an Ansoff matrix serve to help with making trade-off decisions. They’re each based on what is known about products and the markets they potentially operate in.

The four components are market penetration, product development, market development, and product/market diversification:

The decision-making power behind the Ansoff matrix has a lot to do with its ability to make the level of relative risk immediately apparent. There is a big difference between making adjustments to an existing product, in a familiar market, as opposed to playing in a completely different product and/or market space.

The four areas that an Ansoff Matrix focuses on are:

Risk is not the only factor worthy of consideration when making decisions about product-market fit, however. The flip side to risk is reward. And often, the highest potential reward tends to land in the upper right quadrant. Let’s take a look at each of the four components in greater detail.

We’re certainly on familiar terrain when it comes to evaluation of market penetration. When we’re working in this quadrant, we’re looking at products that already exist, and where we’re selling those products into an existing market.

For this and subsequent examples, let’s say we work for a company that makes chewing gum, and let’s call this company Chewing Yum. Let’s further suppose that at Chewing Yum, our products focus primarily on health-conscious adults, and that our product distribution is limited to the United States.

At Chewing Yum, our market analysis tells us that we’re seeing consistent erosion in market share. Given that information, we might decide to embark on a number of relatively low-risk strategies to address this situation, by experimenting in areas such as:

For example, we might choose to experiment by dropping the price, for:

We might even find that by swapping one ingredient with another, we can get more flavor, we can get a lower cost, or we may find that our customers are more likely to buy our product if it’s located in the health section of the store.

As we move into the lower right quadrant of the Ansoff matrix, we’ve entered the domain of introducing new products into existing markets. In some cases, when we say “new product,” it could mean releasing an existing product with significant modifications, it could mean a brand new product that takes us in a significantly different direction as a company, or multiple other variations around the same theme.

On the less ambitious end of the spectrum, let’s suppose that our Chewing Yum market research tells us that our product packaging would be more likely to generate sales if we gave it a fresh look, and we’ve decided to do that in conjunction with changing the name of an existing product (where we’ll have a bold new marketing campaign associated with those changes). And that product re-launch in turn might lead to an idea for a brand new product.

On the more ambitious end of the spectrum, let’s say that we’re looking closely at our competitors, and that we’re seeing an opportunity to increase our market share via some form of acquisition. For example, we might decide to:

Market development takes us into the upper left side of the Ansoff matrix, where we seek to find new settings in which we can sell our existing products. Also known as market extension, market development offers a number of approaches that we could potentially consider.

At Chewing Yum, we might very well have found via research that we have a significant growth opportunity if we explore selling our products outside of normal retail outlets, where we can reach more health-conscious people by partnering with health clubs or health spas to sell our products into several large, well-established partners in that space. We might also have found that we can significantly expand our market share by moving into online sales, to enhance our more traditional distribution channels.

And looking further afield, let’s suppose that we see a particularly promising opportunity in the English-speaking European market, where we can potentially dramatically increase our reach without making changes to product packaging or branding. We might even catch a break because a prominent health guru has mentioned our product on a television show or a podcast, which opens the door to one or more additional potential markets.

The fourth and final quadrant of the Ansoff matrix is the upper right quadrant. It is here where we can potentially explore opportunities that may come with the largest possible payoff, but these often are accompanied with the largest potential risk.

Given that the potential for surprises is the greatest when exploring diversification, it’s especially important for our market research to be particularly robust. Indeed, we might decide that we are not yet ready to explore diversification until we invest in further research and data collection.

The good news is that at Chewing Yum, we’ve done our homework. Thanks to our research, we envision a phased approach, where we envision introducing new products, and also entering new markets. It can be helpful when thinking about diversification to break it down into a couple of sub-categories. Let’s call these categories:

In parallel diversification, the changes that we’re contemplating with respect to new products and new markets are largely in alignment with our existing branding and product offerings.

At Chewing Yum, we’ve decided the first part of our diversification strategy will be to augment our market share by introducing a new product line focusing on a younger audience. And as part of the launch of the new product line, we plan to expand into the English-speaking component of the Canadian market, because we see less competition in that space than we do in some other markets for our new product offering.

In orthogonal diversification, we’re going in a significantly new direction for our company. At Chewing Yum, we’ve discovered that there is a growing market for chewables for pets (dogs in particular). To expand into this market, we’re going to offer a new product line that acts as a dietary supplement and also cleans the dogs’ teeth and gums. As part of this product launch, we’re going to initially sell into existing markets, and also explore the possibility of exploring into new markets.

Note: There are additional ways to articulate forms of diversification, which we won’t delve into here. For instance, some practitioners distinguish between horizontal diversification (similar to what I’m calling parallel diversification) and vertical diversification. In vertical diversification, a company might choose to increase how much it is involved in different parts of the value chain. For instance, a company might choose to focus its diversification activities more on the top of the funnel, or it might choose to diversify in areas such as procurement and manufacturing.

Let’s now turn to advantages and drawbacks associated with the use of an Ansoff Matrix. Advantages include:

As is the case with any decision-making tool, it’s important to recognize the strengths, and also the weaknesses, inherent in the approach. Examples of disadvantages associated with Ansoff matrix usage include:

Given both the advantages and the disadvantages associated with usage of an Ansoff matrix, it is common to use it in conjunction with other techniques. To name a few examples:

Based on the preceding examples, using our fictitious Chewing Yum company, we have seen some of the most common ways in which organizations can use an Ansoff matrix. As such, it most often serves as a decision-making tool, enabling people in various parts of an organization to explore their growth options. Due in large part to its simplicity, and to its visual nature, it’s an excellent tool to include in any organization’s decision-making toolbox.

Because of its structure, an Ansoff matrix also serves as a reminder about certain realities in any organizational context. That is, it illustrates how business growth is possible without product or market development. And it also shows what options might exist in the middle ground, by expanding either products or markets, without relying on more risky diversification strategies.

Featured image source: IconScout

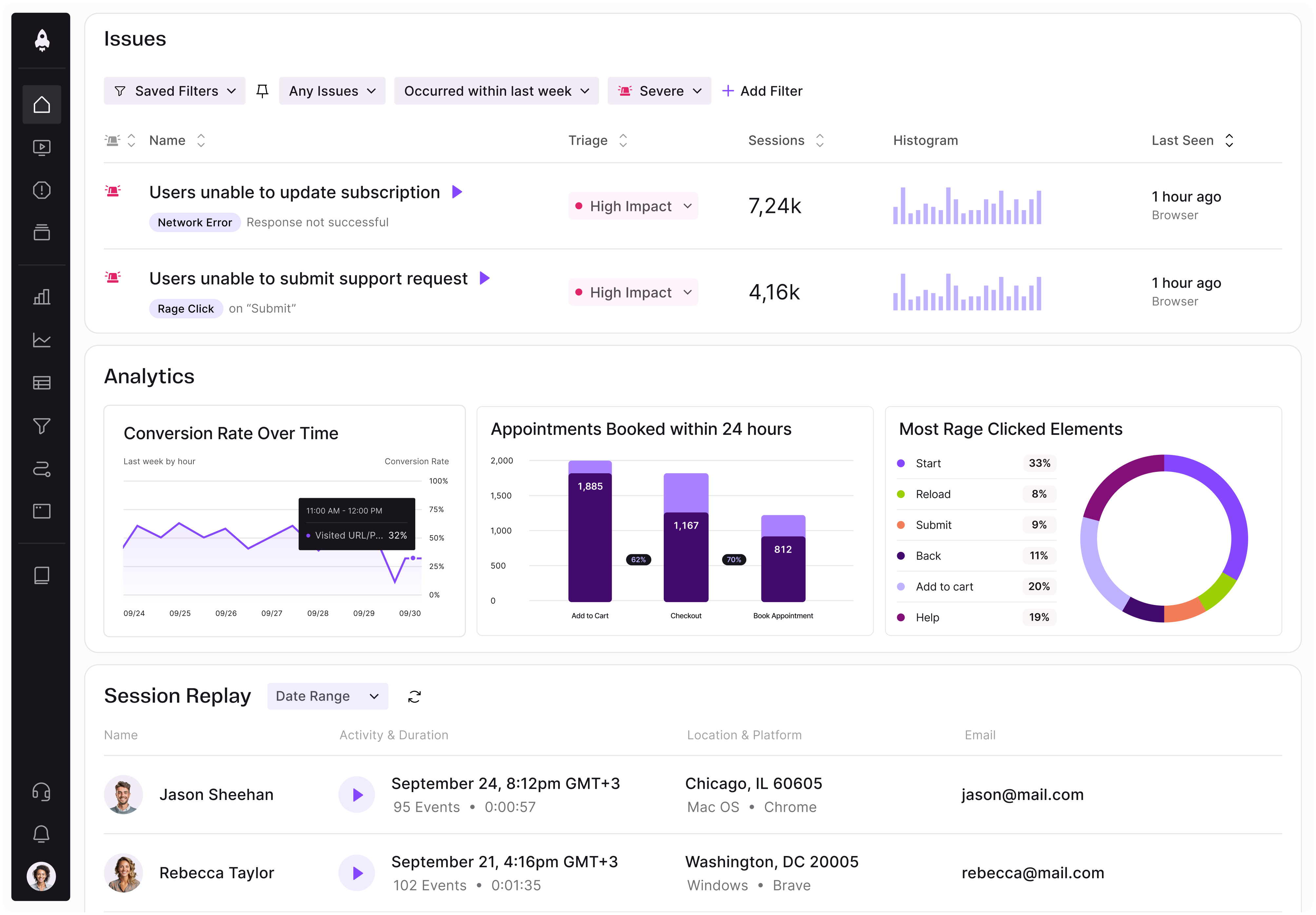

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

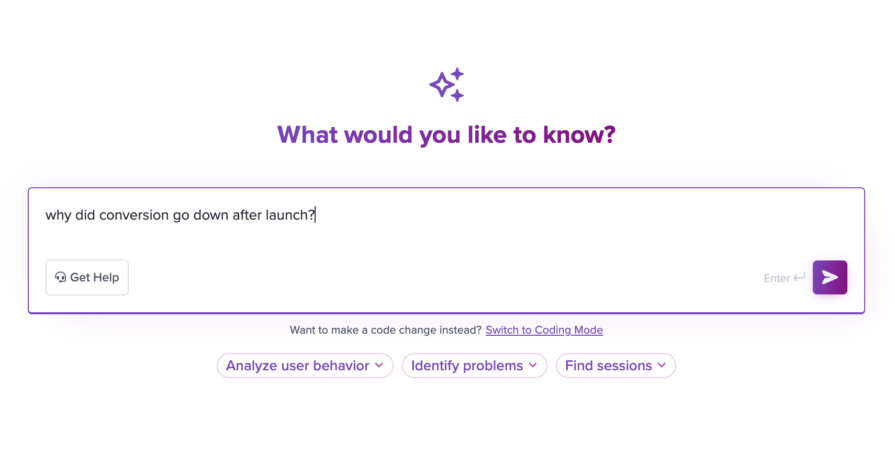

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.