In business, the only thing as certain as death and taxes is risk. However, I’ve noticed an increasing trend of risk-aversion among product people. A lot of PMs want to be certain a potential product or feature is guaranteed to drive business value before embarking with development efforts.

This leads to two dangerous mistakes:

Today I want to talk about the second problem in particular.

Quick wins are short-term, incremental, low-risk projects that are likely to generate a relatively small return. These are the projects that keep the lights on. Big bets on the other hand are those long-term, high-risk bets that if they pan out lead to a high return and may even redefine your market position.

By understanding four important truths about big bets, you can create a healthier mix of short and long-term ideas:

Broadly speaking, quick wins come in three categories:

I’ll demonstrate below how sticking to these categories stifles innovation.

Let’s say you’re tasked with improving the new user experience. You build a nice funnel report that shows you how your users move through each step in your onboarding journey up until their aha moment. You shadow new users as they struggle with your product for the first time.

Great. You now know through quantitative data where your biggest friction points are and from qualitative data why your users are stumbling (or leaving) at that point.

Optimization time! You can be almost certain that by reducing the identified friction points, you will improve your new user experience. Yay you, you nailed it. Right?

Nope, not quite.

Small, incremental optimizations will help you get a little better, but it’s unlikely that you’ll find a massive breakthrough that makes you stand out from the crowd.

With the rise of empowered product teams we love to bash “old-fashioned” stakeholder-driven organizations, but in truth, there’s nothing wrong with implementing the exact features that have been requested by 20 plus customers if they fit your ideal customer profile and their solution-idea is the best fit for their underlying need.

You can be quite sure that you’ll at least make some people happy.

However, great innovative ideas usually don’t come directly from customers. As Henry Ford famously didn’t say,

“If I would have asked the people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

It’s oh-so tempting to get stuck playing the feature parity game. In some cases, it’s necessary to make sure you’re on par with the competition.

If most sales deals are lost because you’re missing a feature that everyone else has, you’re going to need to catch up. If “all” direct competitors have something that you’re missing, this is viable market data to take into account when making a decision. However, most scale-ups I work with don’t want to be on par with the competition. They want to be better.

Flashback to 1997. Three years after founding, and still four years away from profitability, Jeff Bezos writes a letter to Amazon’s shareholders stating his preference for long-term ideas in crystal clear terms:

“We will continue to make investment decisions in light of long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability considerations or short-term Wall Street reactions.”

In his 2003 letter to shareholders, Bezos details some of the big bets the company has taken. Here’s how Jeff explains some of the moves that most e-commerce companies wouldn’t dare attempt, even today:

“Among the most expensive customer experience improvements we’re focused on are our everyday free shipping offers and our ongoing product price reductions. Eliminating defects, improving productivity, and passing the resulting cost savings back to customers in the form of lower prices is a long-term decision. Increased volumes take time to materialize, and price reductions almost always hurt current results. In the long term, however, relentlessly driving the “price-cost structure loop” will leave us with a stronger, more valuable business. Since many of our costs, such as software engineering, are relatively fixed and many of our variable costs can also be better managed at a larger scale, driving more volume through our cost structure reduces those costs as a percentage of sales. To give one small example, engineering a feature like Instant Order Update for use by 40 million customers costs nowhere near 40 times what it would cost to do the same for 1 million customers.”

Long-term thinking is anchored in Amazon’s leadership principle “ownership,” which states that leaders “think long term and don’t sacrifice long-term value for short-term results.” For Amazon, these principles aren’t just a cute statement on the website or an inspiring quote in Helvetica on the office wall. They are ingrained in everything the company does and an integral part of the company’s hiring and employee growth system.

Amazon is not the only example of a company achieving success by actively choosing long-term over short-term gains. Other famous examples include:

Low-hanging fruits feel safe because the returns are almost certain and come in quickly.

However, exclusively choosing low-hanging fruits naturally stands in the way of innovation and will block you from distancing yourself from the competition.

Companies that only go for low-hanging fruits tend to either fail or become “zombie” companies, stumbling along in mediocrity indefinitely but never reaching any great heights.

Big bets are strategically important, but not everything you do should be a moonshot, go-big-or-go-home kind of idea.

Most big bets are gambles and it’s not great business sense to put all of your money on 24 black. Even if the risk isn’t that high, but the time horizon is long, you need to push out small increments of value while you’re working on the next big thing.

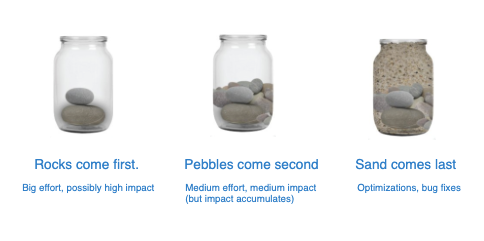

Many experts, such as Lenny Rachitsky and Nels Gilbreth, advise choosing a mix of 20 percent big bets and 80 percent quick wins in product strategy. PayPal uses a “rocks, pebbles, and sand” approach. When planning a roadmap, rocks come first and represent ideas that require the biggest effort. but could have a big impact. The rocks are followed by the slightly less impactful pebbles. Sand — the small optimizations, bug fixes, etc — comes last:

It’s all about balance and allocating resources wisely. Apple is famous for ruthlessly killing off old product lines, so that it can focus its resources on looking into the future and experimenting with new technologies and ideas.

As an individual contributor, quick wins can be useful when you join a new company. You’ll likely need to show some positive results fast to gain trust so that you can take bigger swings later on.

Just because ideas have a long time horizon, a high cost, or a high-risk factor associated with them, doesn’t mean you can reduce risk along the way. Experimentation is the key.

I will always argue fiercely against hiding a ground-breaking idea in stealth mode for up to 12 months. The risk of not having collected any real-world feedback before investing significant time and funds always outweighs the risk of your idea getting stolen. Especially if it’s such a big bet that most incumbents wouldn’t want to burn their fingers on it anyway.

There’s almost always a way to break down a big bet into smaller experiments that can give you some signal as to whether you’re on the right path. If done right, your quick wins teach you about your product, your market, and your customers, which will inform your big bet strategy.

Although this article has advocated for making big bets, there are situations that can hamper your ability to do so. These generally come from financial pressures and company culture.

Of course, deciding on your blend of quick wins and big bets depends on how your finances are secured. For a bootstrapped startup, you may need to prioritize safe choices just to know you’ll have enough revenue to drive any long-term initiatives.

For a PE or VC backed startup your choices need to be (at least somewhat) aligned with your shareholders’ wishes. Going back to the example of Amazon: Jeff Bezos brought his shareholders along from the very start. Your company might not be in the same position.

You won’t be able to push through a big-bet way of thinking if the company culture is fully focused on securing small gains in KPIs and isn’t very interested in innovation. As a business leader, it’s up to you to encourage your team to go after innovative, out-of-the-box ideas, and ensure you keep that healthy mix of quick wins and big bets.

If the culture isn’t right, you have two choices: accept, or leave.

As a product manager, making decisions on what to develop next is the most difficult and important part of your role. That said, you need to balance long term investment with quick wins if you want to be competitive in your market. Companies that only prioritize quick wins end up getting leapfrogged by those who are willing to take bigger risks.

If you come away with one thing from this article, try to resist your urge to be as risk averse as possible. Risk is inevitable, but it’s also what makes the big wins possible!

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Deepika Manglani, VP of Product at the LA Times, talks about how she’s bringing the 140-year-old institution into the future.

Burnout often starts with good intentions. How product managers can stop being the bottleneck and lead with focus.

Should PMs iterate or reinvent? Learn when small updates work, when bold change is needed, and how Slack and Adobe chose the right path.

AI accuracy problems are often chunking problems. Learn how chunk size and structure impact cost, retrieval quality, and UX.