Josh Petrovani Miller is Senior Director of Product Management at Talkspace. He began his career in finance as an equity research analyst before joining UltraLinq Healthcare Solutions as a product analyst. From there, Josh then transitioned to product management at The Knot Worldwide, a global technology company, before moving to Talkspace.

In our conversation, Josh talks about the traditional, centralized approach to making big swing product decisions and how he advocates for using a different, less overwhelming method. He discusses the importance of autonomy in product teams and what it means to be truly results-oriented. Josh also shares his experience launching products at startups and early-stage companies.

Like most PMs, I started in product before I knew it had a name. Back in 2015, I was working in finance and connected with an inspiring founder, Cynthia Petterson. She was building Share Hope, a social enterprise and nonprofit in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Through strategic connections, training, and quality processes, the company helped factories doing low-skill government manufacturing graduate to high-skill manufacturing. Essentially, this meant a higher margin and better conditions for workers.

All of the profits from this business were invested in social programs for garment workers through the nonprofit on a wholesale model. I found the opportunity to pitch the founder with the idea of developing a direct-to-customer model. This was in the heyday of Casper, Warby Parker, and a huge wave of D2C startups. I was covering consumer retail companies in my day job and thought, “We should get in on this.”

The first product I launched was black, high-waisted, supportive women’s leggings. I managed everything — from the garment’s design to the branding, product photos, delivery, and shipping. All this came together in an online Shopify store. I was doing this during evenings and weekends, alongside my demanding job in finance.

When it comes to pre-build products, there are two categories. One is when you’re in a startup and launching something new. The other is when you’re working on a new product for an established company.

In a startup, it’s relatively simple. You make sure you’re solving real customer problems, and the product is something people care enough to pay for. You just need to be aligned with your teammates on what you’re doing and why. You focus on the product and the customer. But when you’re launching new products inside a company with an existing business, the challenges are very different. In addition to discovery and product vision, you’re managing relationships with this existing business.

The most crucial things for a pre-launch phase are high-level buy-in from the executive team, an executive team that’s willing to invest in resourcing the initiative, and addressing internal barriers to launching. When you think about a new product or feature, it often requires things like a different appetite for risk. This level of buy-in and door opening is crucial, and to get there, you need a compelling opportunity, a clear plan, and a lot of trust that you can deliver.

Certainly, but the bigger challenge is actually business and alignment — you need to hook up the new idea to all these other processes that are already working. If you can do that successfully, you can have a great launch and gain strong momentum. But if you miss the mark — whether it’s failing to align with the marketing lifecycle, ensuring sales teams are adequately trained, or other key factors — you risk a less impactful launch.

The process is constantly evolving. No matter how often you update people, the vision will adapt as the product evolves.

I like having a structured approach that combines both asynchronous and synchronous communication. At Talkspace, the product team holds a monthly presentation that is about 30 minutes long. Anyone can drop in and learn exactly what we’re doing, what we’re learning, and how the vision is changing. We also send asynchronous updates on specific initiatives when things need focused attention.

Another strategy I use is holding biweekly meetings with the most important stakeholders. We call it the project acceleration committee — we talk through where we are, what the blockers are, and how we can push through things faster. I’ve been able to get our chief marketing officer and head of commercial to be there, etc. Having these people in the room allows us to address barriers on the spot and find solutions together.

This is a question of aligning a team of people, giving them enough autonomy to use their judgment and make an impact, while also holding enough control that everyone is running in the same direction. That’s what results-oriented usually means. Does the PM have an incentive? Do they know they’re on the line for a launch and that people are watching, or that they’re in line for a metric they need to move?

The bigger challenge is getting everyone rowing in the same direction and maintaining the right level of autonomy.

Most companies navigate this by using centralization to make big swing decisions. The executive team might decide, “We’re going after this market now,” and then give autonomy in executing that vision. In the planning process, they solicit feedback from the team but largely focus on incremental improvements. The problem with this approach is that the big swings often come out of nowhere for the team, leaving them frustrated that their ongoing work is being overlooked.

I’ve also seen many PMs not aiming high enough. They get so bogged down in the immediate problems without seeing if they could play a different game altogether. I’ve fallen into this in my career, too. To address this, I try to create common ground. People disagree when they have different assumptions, and you need to help get everyone on the same page about core assumptions.

I like to create this common ground with documents that outline and later update my view of the market, who our customer is, what our product is, and how it needs to evolve based on new information. I encourage my colleagues to both give feedback and write their own documents. These fill gaps in what’s missing, help us build more confidence in this strategy, and help us disprove it. I try to build a shared understanding of the current business context, what the strategy is, and what the customer needs are.

It’s funny — I think most PMs spend over 70 percent of their time in project management rather than thinking about the strategy. This is why Talkspace has brought back the role of an associate product manager. Senior product managers often have deep business and technical insights, but they end up spending much of their time tracking the status of various tickets, which can be a significant drain on time and energy.

To operate effectively, teams need a very strong project manager who can keep track of everything while making some judgment calls. We use our associate role in that way so senior PMs can ladder up into the bigger business and strategy aspects of product management.

This is where the shared context comes in. If everyone is on the same page about strategy, we clearly understand the customer’s problems and potential solutions. Where it goes wrong is having a known problem or opportunity with a customer at a specific point in their life and wanting to take it to other markets. It’s my job to partner with the executive driving the initiative and say, “It’s interesting. Tell me what’s happening in this market and what we know about it. What have we tried? What have we already learned? Do we need to devise an experiment to validate that this is a real market for us?”

The job of the senior product person is to sit down with the person pushing this, get in their heads, partner with them, and hone the idea into a much more specific customer opportunity or customer pain point.

One example is from the first time that I built a B2B product. I had been a consumer PM and was brought into my role at Talkspace as a director. I was working with my team on the first enterprise launch of self-guided tools for enterprises. We wanted to partner with enterprises to support their mental health goals by not just giving their employees free access to Talkspace but also providing a whole mental health wellness program.

I treated this like a B2C product. I conducted customer discovery, interviews, and problem definition. We found a great business problem — most companies were paying for benefits with low adoption rates, including Talkspace. Despite the HR team’s efforts to communicate these benefits, many employees are unaware of them. We realized that if even 10 percent of employees utilized a benefit, the ROI for the company would be much higher than if only 1 percent used it.

We came up with what was later launched as Talkspace Engage, a marketing automation tool for HR teams. Though HR teams aren’t always well-versed in how to drive the adoption of benefits, many marketing teams are great at that. We developed a portal with pre-written email copy and a content calendar aligned with the Talkspace app, making it easy for HR to promote benefits. All they had to do was log in monthly, copy the content, and send it out.

We launched the tool, but it was met with silence. It’s easy to blame the sales team for lackluster sales. But what I didn’t know was that our company has this well-developed engine — our enterprise business has a marketing function that does branding and top of the funnel. They gather leads and position us in a certain way. Our sales team finds new leads and nurtures existing ones. I didn’t do a great job engaging with both teams to integrate this new launch into our product offerings, price it correctly, and educate our salespeople about it.

We’re now working on another product launch, and we went about this with an entirely different process. This time, we will hit the ground running. Everyone will have the information they need, and we’ll have this go-to-market acceleration experience. Whether or not the product is a wild success, we’ve done everything to prepare the team, and the salespeople are genuinely excited about selling it. The B2B world is so much more relationship-driven than B2C, and this experience taught me the importance of that integration.

My favorite question to ask myself as a manager when interviewing someone is, “Would I work for this person?” If the answer is yes, it indicates that this is a “hell yes” and not a “maybe yes.” The best people I’ve hired made it here because, to this day, I would work for them in a heartbeat.

When I hire, I look for high agency, structured thinking, systematic work, creativity, curiosity, and passion. They’ll likely succeed in the role even if they’re a little light in experience. If I hire someone who has done this before, I get their experience, but a wildly curious person who has high agency and thinks carefully can have more impact.

You can’t make anyone do something they don’t want to do, but you can demonstrate it in your own behavior. I’m continuously learning, and in many ways, I set the pace for learning and culture in my team. I openly share what I’m passionate about and learning with them.

I also have a 1:1 doc that I share with all of my direct reports. We add a new date, time, and meeting summary each week. At the top of that document are my direct reports’ goals, what they’re trying to learn, and where they’re trying to grow. Every week, though there are tactical things that we’re trying to get through, we’re always looking at where we’re trying to go professionally and how we want to grow. This becomes an anchor and helps people feel a sense of momentum, continuous learning, and a way to check in throughout the process.

If we consider the role of a product manager from first principles, it’s clear that PMs exist because, as Patrick Collison of Stripe puts it, “It’s hard to reliably turn capital into good software.” It’s like building a bridge as well as making a movie. The process is highly technical because you have to know how to build software, and you also have to have this energy to it. Further, you have to produce a good user experience to continuously raise the bar of quality.

We’ve seen a shift toward having program managers and project managers, which is very positive. We screen PM candidates by looking for strategic thinkers, but when 70 percent of the role is executing and project management, we’re not necessarily screening for the kind of person who will find that type of work especially life-giving.

In my experience, and this is a little contrarian, a great product designer is much better than a decent product manager. A great product designer doesn’t need that much input from a PM. Once they understand the problem, they can go to town with a technical partner and come up with a truly excellent solution that is appropriate in scope and deeply solves the customer’s needs. Many PMs end up in this role to come up with solutions, which, in places like startups, is key. However, we can often get better outcomes by having designers, engineers, and a few senior product people.

I believe that the PM role will evolve to be more senior and specialized over time. There will be more program and project managers, and there will also be a higher ratio of designers. As product managers mature in their careers, many may transition into more specialized roles such as product design or program management. My prediction is that as people grow, they will transition from generalists into more specialist roles.

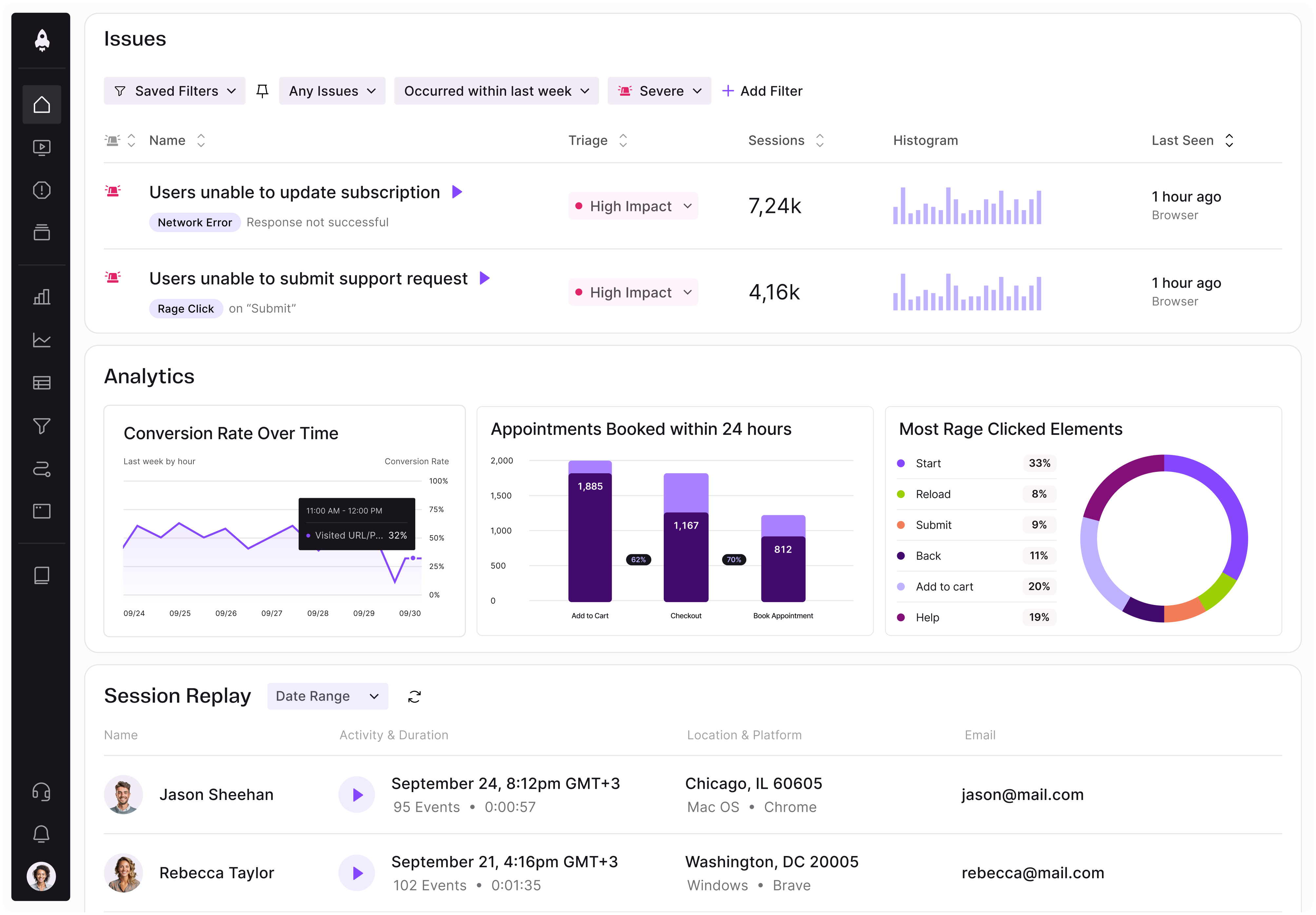

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

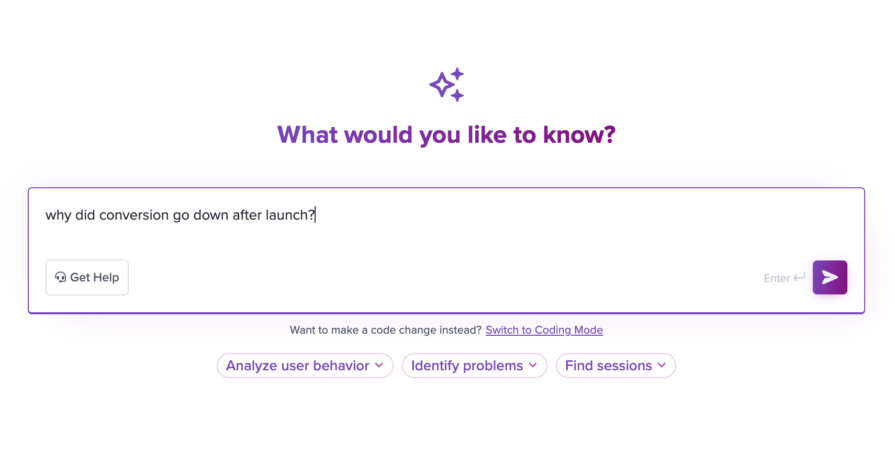

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.