We often hear about products that “went viral.” But what does it even mean?

Or, even more importantly, how can you build a product that will be the next viral hit?

Product virality is the most efficient, cheapest, and yet hardest-to-grasp growth engine you can build. In this article, I’ll break it down into smaller, clearer parts and give you actionable tactics on how to improve the virality of your own product based on examples from companies like Snapchat, Uber or Dropbox.

After all, many of the unicorns we hear about are products that grew thanks to a robust viral growth engine.

There are four fundamental ways to acquire new users:

Product virality refers to the phenomenon where a product gains rapid and widespread popularity primarily through user referrals, word of mouth, or inherent sharing features. It is a growth mechanism in which existing users play a pivotal role in acquiring new users, amplifying the product’s reach organically.

The foundation of a viral growth channel is your current users, whose actions lead to the acquisition of brand-new users. It can come through direct invitations or just word of mouth.

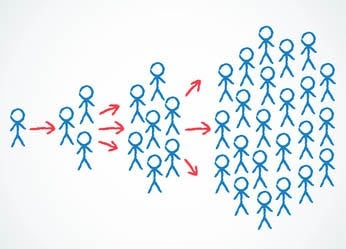

We often say that a product “went viral” if, on average, one existing user leads to acquiring one or more brand new users to the platform:

For example, if you have 10 users and, by word-of-mouth, invitations, or any other type of virality, they lead to 20 new users, which then, over time, lead to 40 new users, and so on, your product is truly viral.

Virality can mean different things for different products. There are multiple categories of product virality, but we can bucket most of them into three main types of virality:

Let’s dive deep into each of these buckets using real-world examples.

Word of mouth happens when users talk about your product without being asked to, either online or offline.

By online word of mouth, I mean activities such as:

People usually do this for one of three reasons:

Let’s take Clubhouse as an example. Because, in its early stage, it was a premium, invitation-only platform, openly mentioning when you had access to Clubhouse could boost your ego. Knowledge and insights shared on Clubhouse weren’t recorded and stored, so the only way to share it was to talk about what you heard in Clubhouse rooms.

Combining these two reasons with the fact that celebrities often participated in Clubhouse rooms made the topic quite popular online, incentivizing frequent sharing to get likes and followers and further boosting the product’s virality.

Offline word of mouth happens when a product is a daily part of people’s lives so they unintentionally mention it in various contexts.

Uber is a perfect example. People are always saying phrases like “I’ll take an Uber.” That encourages people who hear it to try out Uber themselves, and the viral cycle repeats.

Invites are the easiest type of virality to build into your product and also the easiest to track.

We talk about invite virality when users actively and intentionally try to bring their friends, colleagues, or even random people to the product. There are three main reasons for users to do so:

Some products are simply better with friends.

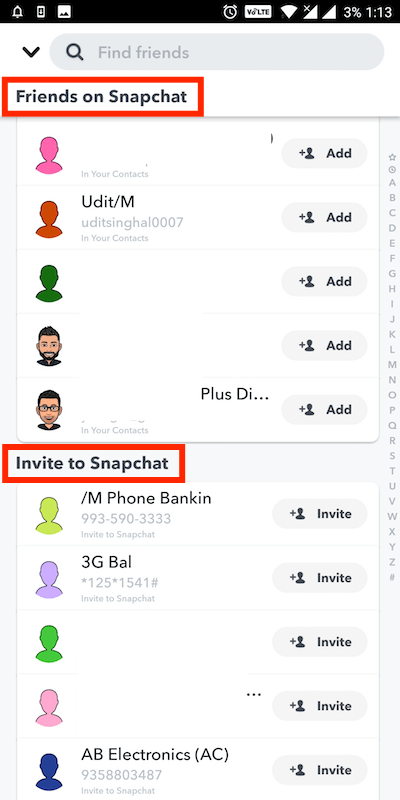

This type of virality prevalent on social media platforms such as Snapchat:

People who fell in love with the idea of vanishing, story-like pictures invite their friends and colleagues so that:

Adding friends to the platform simply makes the experience 10 times better than just interacting with random people.

Another reason to invite people to a product is to get a reward.

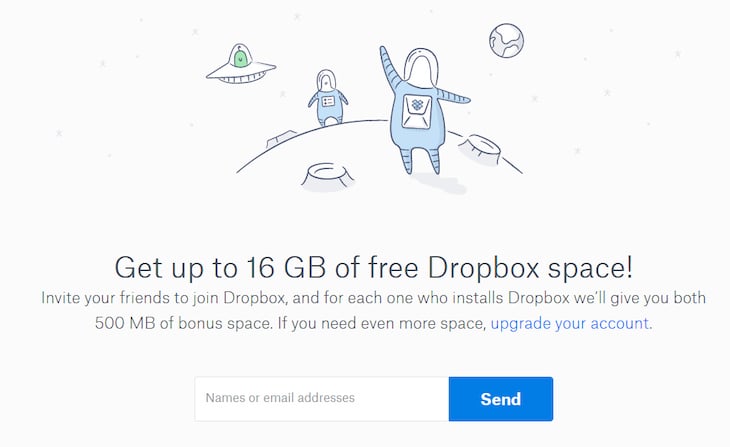

This rewarded invitation is one of the main factors that led Dropbox to become such a popular and successful product:

With limited GB storage, users are incentivized to bring more people to get extra MBs for free. And because the increased storage capacity boosts the value of the product tremendously, the incentive is strong.

Some people even promote their invitation links to random people on the internet just to get some extra space.

Some products simply don’t work if you don’t invite colleagues to use them.

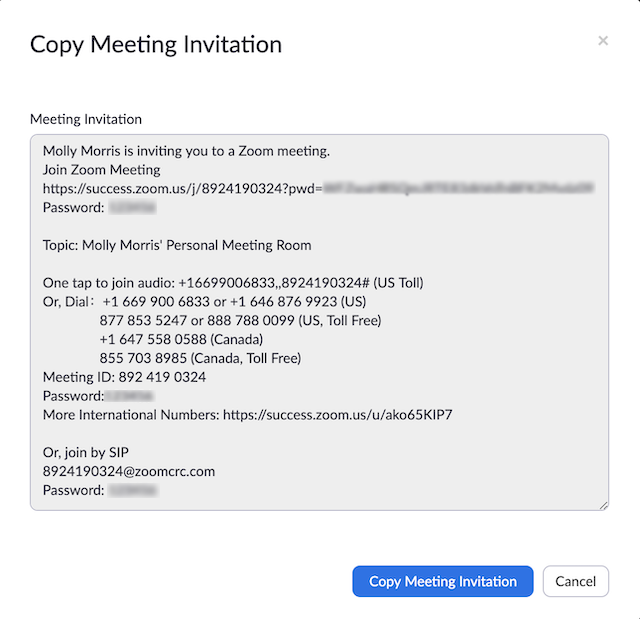

Let’s take a look at Zoom, for example.

To have a virtual meeting with someone, that person also must be using Zoom, so the mere act of sending someone a meeting link is already an indirect invitation to use the platform:

The same goes for hosting webinars or virtual conferences. And when people join Zoom meetings or webinars, they can see the product in real life, interact with its features, and, ultimately, get hooked themselves.

Once they do, they’ll need to send the Zoom link to their colleagues and audience to interact with them via the platform, and the cycle repeats.

Experiential virality happens when one person using the product leads to other people experiencing the product, even when they don’t talk about it or invite others.

We can distinguish two types of experiential virality:

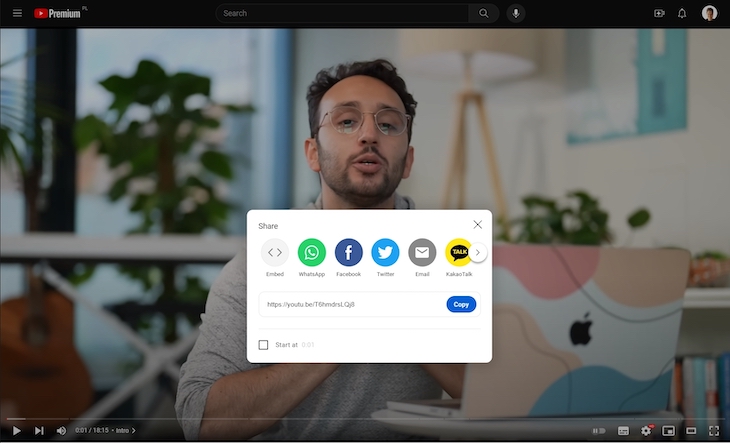

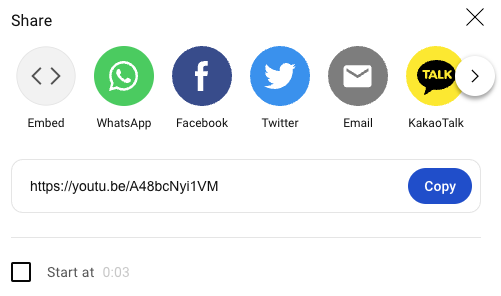

Actively shared virality is most common for content platforms such as YouTube. Say you watched a funny cat video and want to share laughs with friends. What do you do?

You share the link with them:

You don’t talk about YouTube itself, nor do you require them to join the platform, create an account,, etc. You just share a link. But because the platform is heavily branded, people quickly associate YouTube with “the place you go to watch videos online.”

YouTube’s recommendation engine also does a great job of keeping users on the platform longer. Who among us haven’t binge-watched dozens of videos after jumping on the platform just to watch something a friend shared?

Think about your own journey with YouTube. Did someone openly talk about the platform and its benefits? Did you get an invitation from a colleague? Probably not.

Most likely, you just watched a video hosted on YouTube here and there a few years back, and you don’t even remember when you became a frequent user.

Sometimes, people can get hooked to a product by just passively seeing it in action.

Netflix is the perfect example. One of its early growth engines was heavily based on passively seen virality. The story usually looked like the following:

Your friend invites you to watch a movie together, you visit, and then they fire up the whole movie library on their TV. You are surprised and ask what it is and why they don’t need a DVD. Then they explain what Netflix is, and you become fond of the concept. The more often you see it in action at other people’s homes, the more hooked you are, and then, at some point, you try it out yourself and invite friends over to share the experience.

And the cycle continues.

Now that we covered what virality is and what types of product virality are there, let’s discuss a few tactics for boosting the virality of your product.

The first and probably most obvious tactic is to create social features to encourage invitations.

In addition to social platforms like Snapchat, this tactic is also relevant for products used primarily by a single person.

For example, Uber introduced a feature allowing users to share their trip details and estimated ETA. This encourages users to send links to their friends so they don’t have to update them when they plan to arrive. It creates an extra opportunity for the link receiver to get hooked on the value Uber provides.

Virality is also one of the main reasons food ordering apps introduce bill split functionality. In the past, usually one person ordered the food for a party, and they settled the bill outside of the product, exchanging bank information, etc. The bill split feature makes the whole process smoother and easier, but it often requires everyone chipping in to have their own account to use the feature.

Although they download the app to settle the bill, since they already have the app, there’s a higher chance they’ll use it the next time they need to order food themselves.

If your product generates shareable content, make it stupidly easy and frictionless to share content with friends.

Let’s take another look at YouTube’s sharing feature:

With the press of a button, the user can easily copy a link or even send a premade message via WhatsApp, email, etc. The “start at” option makes the sharing experience even more seamless. It leads to more shares, which leads to more people exploring the product just because they got a link.

The easier it is to share the content from your product, the higher the chance your users will do so, so focus on nailing the sharing experience.

Help users share things that make them feel or look good in front of colleagues. Some examples include:

For example, although EasyQuit is neither a social app nor generates content, users can celebrate their progress with friends and feel good publicly announcing their progress whenever they unlock a new achievement:

A small thing, but it does help to spread the word.

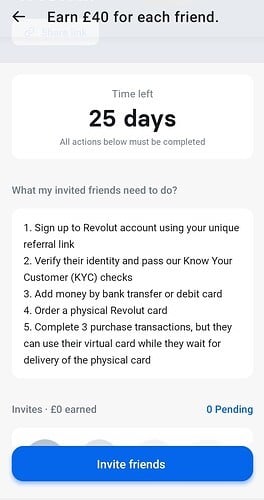

Incentivize your users to invite friends, colleagues, or even random people to use your app.

For example, Revolut gives users actual money for referring new people to use their product, and that strategy was one of the keys to its early success:

You don’t have to default to money, though. Just like Dropbox rewards users with extra storage space and Uber Eats gives you discounts for your next order, all that matters is offering something that’s genuinely relevant to your users.

Just make sure to include the cost of the incentive in your customer acquisition costs (CAC) calculations to monitor whether you are getting a good ROI.

Although I wouldn’t call paid influencers a part of a virality growth channel (rather it’s a form of performance marketing), it might be a good strategy to kickstart word of mouth.

Identify influencers relevant to your target audience and ask them to talk about your product. Odds are some people will start resharing or repeating the message, boosting the word-of-mouth virality of your offer.

Last but not least: just create a truly remarkable user experience.

To put it simply, iIf your product does a fantastic job at solving user needs and improving their lives, there’s a higher chance they’ll talk about it or encourage their friends to also get the benefits.

No acquisition tactic can compare to having a product that’s truly valuable and relevant for your users.

Virality is one of the fastest and cheapest ways to grow your audience.

We can define three main types of virality:

Even if your growth strategy doesn’t rely primarily on virality, most products can get a nice boost in acquisition by implementing virality-focused tactics.

Consider the following to boost your product ingrained virality:

However, even the best virality strategies won’t compensate if your product is poorly designed. The first step to building a viral product is to create a valuable, usable, and enjoyable product.

At the end of the day, although products like Dropbox, Snapchat, YouTube, Uber, and Revolut had solid virality strategies in place, the key factor that helped them to get traction was simply the fact that these are just great products people wanted to talk about and share with colleagues.

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

A fractional product manager (FPM) is a part-time, contract-based product manager who works with organizations on a flexible basis.

As a product manager, you express customer needs to your development teams so that you can work together to build the best possible solution.

Karen Letendre talks about how she helps her team advance in their careers via mentorship, upskilling programs, and more.

An IPT isn’t just another team; it’s a strategic approach that breaks down unnecessary communication blockades for open communication.