As web apps continue to grow in complexity and size, so do performance concerns. Developers often address this by adopting server-side rendering (SSR) to offload some of the rendering processes from the client.

However, site performance can still take a hit even when HTML rendering happens on the server. While HTML is delivered in a fast and SEO-friendly manner, the process of hydration — making the app interactive on the client-side — can be costly. In turn, metrics like Time to Interactive (TTI) and Estimated Input Latency (EIL) can plummet for apps with complex, deeply-nested HTML.

Now, you could solve this with techniques like code-splitting, or loading the vital parts of the app immediately while delaying the delivery of code, and hydrate the other components. This might improve your metrics but will still waste load time on components the user never sees or interacts with.

That’s where lazy hydration steps in. Let’s see what that is, how it works, and how to implement it in Vue 3.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

To understand the variants of hydration and how they work, you first need to familiarize yourself with partial hydration.

As the name implies, in partial hydration, you hydrate only certain parts of your app. This is useful when implementing so-called “islands architecture”, where different app sections are considered separate entities. This makes each section of the app function independently from the others, which allows them to hydrate separately.

Let’s think about how partial hydration and islands architecture would apply to a website like a blog. You could hydrate the interactive parts like the toolbar and comment section, but leave other parts like the content itself completely static. Such an approach improves your website’s performance and UX, and no resources are wasted on static content, making the interactive parts hydrate faster.

Lazy hydration builds upon the concept of partial hydration and takes them even further. The concept is similar in implementation for any framework that has SSR, basic hydration, and async components already included.

Instead of only being able to decide what parts of the web app should be hydrated, you can also decide when that should happen. For example, you can hydrate the component only when idle, when it’s in the viewport, or in response to various other triggers like Promise resolving or user interaction.

This takes resource-saving and performance optimizations to another level. You no longer have to hydrate components the user will never see or interact with, making TTI nearly instantaneous!

Vue 2 had a great, fairly popular library named vue-lazy-hydration. It provides a renderless LazyHydrate component and a bunch of manual function wrappers like hydrateWhenVisible for wrapping the components you want to lazy-hydrate. It also allows you to hydrate on different conditions, such as:

requestIdleCallback)IntersectionObserver)click, mouseover, etc.)Promise, boolean switch, etc.)never (for static, SSR-only components)Sadly, at the time of publication, this, nor any other prominent lazy hydration library doesn’t support Vue 3. With that said, the vue-lazy-hydration support for Vue 3 is in development and it appears there is a plan to release after Nuxt 3 comes out.

This leaves us to either continue using Vue 2 for lazy hydration, or to implement our own mechanism, which is what we’re going to do in this article.

With UI frameworks like Vue that have inbuilt SSR and hydration support, implementing lazy hydration is rather easy.

You’ll need a wrapper or renderless component that automatically renders your component on the server while using conditional rendering on the client-side to delay hydration until certain conditions are met.

I decided to base our implementation of Vue 3 lazy hydration upon react-lazy-hydration. Its code is simpler than vue-lazy-hydration’s and is surprisingly more translatable, with React Hooks converting nicely with the Vue Composition API.

We start with a base Vue 3 component, with additional TypeScript inclusion and an isBrowser utility function for checking whether browser globals are available.

<script lang="ts">

import { defineComponent, onMounted, PropType, ref, watch } from "vue";

type VoidFunction = () => void;

const isBrowser = () => {

return typeof window === "object";

};

export default defineComponent({

props: {},

setup() {},

});

</script>

<template></template>

Our lazy hydration wrapper will include similar functionality to what the previously mentioned libraries provide. For that, we’ll have to accept a fairly broad set of config props.

// ...

export default defineComponent({

props: {

ssrOnly: Boolean,

whenIdle: Boolean,

whenVisible: [Boolean, Object] as PropType<

boolean | IntersectionObserverInit

>,

didHydrate: Function as PropType<() => void>,

promise: Object as PropType<Promise<any>>,

on: [Array, String] as PropType<

(keyof HTMLElementEventMap)[] | keyof HTMLElementEventMap

>,

},

// ...

});

// ...

With the above props, we’ll support SSR-only static components as well as hydrating when the browser is idle, the component is visible, or after the given Promise resolves.

On top of that, on will support hydrating on user interaction, while didHydrate will allow for a callback after the component’s hydrated.

In setup, we first initialize a few required values.

// ...

export default defineComponent({

// ...

setup() {

const noOptions =

!props.ssrOnly &&

!props.whenIdle &&

!props.whenVisible &&

!props.on?.length &&

!props.promise;

const wrapper = ref<Element | null>(null);

const hydrated = ref(noOptions || !isBrowser());

const hydrate = () => {

hydrated.value = true;

};

},

});

// ...

We’ll use a wrapper template ref for accessing the wrapper element and a hydrated ref for holding the reactive boolean value, which determines the current state of hydration.

Note how we initialize the hydrated ref. When there are no options set, the component will be hydrated immediately by default. Otherwise, the hydration will be delayed on the client-side while going through SSR.

hydrate is just a one-way helper function for setting hydrated to true.

Next up, we start creating the logic, with an onMounted callback and a single watch effect.

// ...

onMounted(() => {

if (wrapper.value && !wrapper.value.hasChildNodes()) {

hydrate();

}

});

watch(

hydrated,

(hydrate) => {

if (hydrate && props.didHydrate) props.didHydrate();

},

{ immediate: true }

);

// ...

In the onMounted callback, we check whether the element has any children. If not, we can hydrate immediately.

The watch effect handles the didHydrate callback. Notice the immediate option — it’s important for when hydration isn’t delayed, both during SSR and when no options are provided.

watch effectNow, we get into the primary watch effect that will handle all the options and set hydrated ref appropriately.

// ...

watch(

[() => props, wrapper, hydrated],

(

[{ on, promise, ssrOnly, whenIdle, whenVisible }, wrapper, hydrated],

_,

onInvalidate

) => {

if (ssrOnly || hydrated) {

return;

}

const cleanupFns: VoidFunction[] = [];

const cleanup = () => {

cleanupFns.forEach((fn) => {

fn();

});

};

if (promise) {

promise.then(hydrate, hydrate);

}

},

{ immediate: true }

);

// ...

The effect will trigger changes in props, as well as in the wrapper and hydrate refs.

First, we check if the component is meant to render only on the server-side or if it has already been hydrated. We do this because, in either of these cases, there’s no need to evaluate the effect further, so we can return from the function.

If the process continues, we initialize the cleanup function for when the effect is invalidated, and handle the Promise-based lazy hydration.

Next, still inside the effect, we handle the visibility-based hydration. If the IntersectionObserver is supported, we initialize it, passing either the default or provided options. Otherwise, we hydrate immediately.

// ...

if (whenVisible) {

if (wrapper && typeof IntersectionObserver !== "undefined") {

const observerOptions =

typeof whenVisible === "object"

? whenVisible

: {

rootMargin: "250px",

};

const io = new IntersectionObserver((entries) => {

entries.forEach((entry) => {

if (entry.isIntersecting || entry.intersectionRatio > 0) {

hydrate();

}

});

}, observerOptions);

io.observe(wrapper);

cleanupFns.push(() => {

io.disconnect();

});

} else {

return hydrate();

}

}

// ...

Note the cleanup callback for disconnecting the IntersectionObserver instance from the wrapper element.

We follow a similar structure for browser idle-based hydration, this time with requestIdleCallback and cancelIdleCallback.

if (whenIdle) {

if (typeof window.requestIdleCallback !== "undefined") {

const idleCallbackId = window.requestIdleCallback(hydrate, {

timeout: 500,

});

cleanupFns.push(() => {

window.cancelIdleCallback(idleCallbackId);

});

} else {

const id = setTimeout(hydrate, 2000);

cleanupFns.push(() => {

clearTimeout(id);

});

}

}

requestIdleCallback cross-browser compatibility is lower than 80 percent, notably with no support from Safari on both iOS and macOS, so we’ll have to implement a fallback with setTimeout, delaying the hydration and pushing it to the async queue.

If you’re using TypeScript, you should note that, currently, you won’t find requestIdleCallback in the default lib. For proper typing, you’ll need to install @types/requestidlecallback.

Lastly, we handle user event-based hydration. Here, things are relatively simple as we just loop through events and set event listeners accordingly.

if (on) {

const events = ([] as Array<keyof HTMLElementEventMap>).concat(on);

events.forEach((event) => {

wrapper?.addEventListener(event, hydrate, {

once: true,

passive: true,

});

cleanupFns.push(() => {

wrapper?.removeEventListener(event, hydrate, {});

});

});

}

onInvalidate(cleanup);

After that, remember to call onInvalidate to register the cleanup function, and the effect is ready!

To finish off the component, return the refs needed in the template from the setup function.

// ...

export default defineComponent({

// ...

setup() {

// ...

return {

wrapper,

hydrated,

};

},

});

// ...

Then, in the template, render the wrapping <div>, assign refs, and conditionally render the component for lazy hydration.

<template>

<div ref="wrapper" :style="{ display: 'contents' }" v-if="hydrated">

<slot></slot>

</div>

<div ref="wrapper" v-else></div>

</template>

With our lazy hydration component ready, it’s time to test it out!

First, you’ll need to set up your environment that is either SSR- or Static Site Generator (SSG)-ready. Technically, anything with pre-rendered HTML and Vue 3 with hydration enabled should work, but your mileage may vary.

As neither Nuxt.js nor Gridsome is compatible with Vue 3 just yet, your best bet would be to go with something like vite-plugin-ssr. Such a solution will allow you to take advantage of the great development experience Vite provides while implementing SSR without much trouble.

You can scaffold a new vite-plugin-ssr app with the following command:

npm init vite-plugin-ssr@latest

Then, set up the lazy hydration component, either with the guide above or from this GitHub Gist.

With that in place, go to any available page, wrap an interactive component inside <LazyHydrate> and play with it!

<template>

<h1>Welcome</h1>

This page is:

<ul>

<li>Rendered to HTML.</li>

<li>

Interactive. <LazyHydrate when-visible><Counter /></LazyHydrate>

</li>

</ul>

</template>

<script lang="ts">

import Counter from "./_components/Counter.vue";

import LazyHydrate from "./_components/LazyHydrate.vue";

export default {

components:{

Counter,

LazyHydrate,

}

};

</script>

Use different options, see when the component’s interactive, check out when it’s hydrated with the didHydrate callback, and more!

To further improve your app’s TTI metrics and loading times, you can combine lazy hydration with async components. This will split your app into smaller chunks, ready to be loaded on-demand. With that, your lazy-hydrated components will only load when the hydration happens.

import { defineAsyncComponent } from "vue";

import LazyHydrate from "./_components/LazyHydrate.vue";

export default {

components: {

Counter: defineAsyncComponent({

loader: () => import("./_components/Counter.vue"),

}),

LazyHydrate,

},

};

Keep in mind that you’ll have to be careful with this approach, as dynamically fetching components might create a noticeable delay for the user. In this case, you’ll have to be selective about which components to defer and will need to implement fallback content, like loaders for when the code is fetched and parsed.

However, even with all of that to consider, lazy-hydrated async components can still have great potential for drastically improving the performance of large and complex apps, especially those that heavily rely on elements such as interactive graphs or hidden dialogs.

So there you have it — lazy hydration explained and implemented in Vue 3! With the component implemented in this post, you can optimize your SSR/SSG app, improve its performance, responsiveness, and user experience.

For the complete code of the <LazyHydrate> component, check out this GitHub Gist. Feel free to experiment with it. If you’ve got any ideas for improvement, let me know over on GitHub.

Be sure to follow updates on vue-lazy-hydration. The next version is said to take advantage of new Vue 3-Node APIs and thus is likely to be more performant or provide more features than the simple implementation from this post.

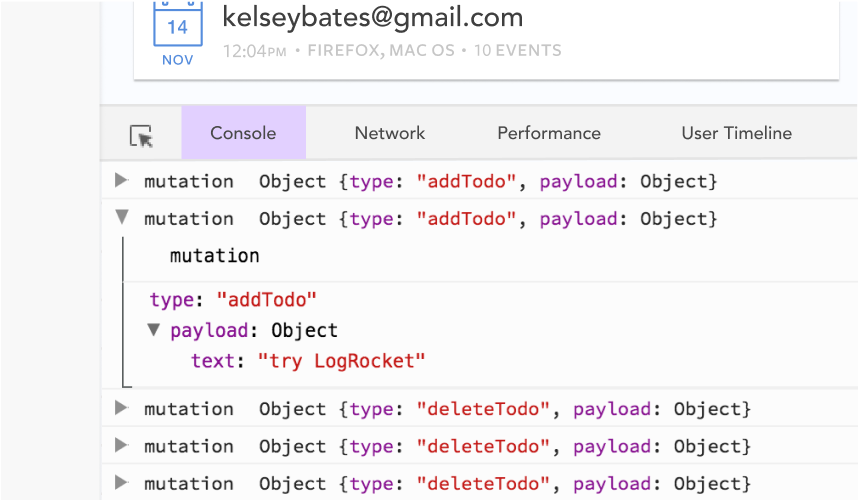

Debugging Vue.js applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are difficult to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking Vue mutations and actions for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug your Vue apps — start monitoring for free.

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now