Metrics are a wonderful part of being a product manager. They are the source of insights, hypotheses, validation, and understanding. But they can be all-consuming and confusing if you don’t know where to focus your energy.

In this guide, we’ll introduce you to various types of product metrics and help you determine which ones you should focus on as a product manager, depending on your product and business.

Product managers and teams encounter a wide range of metrics that are either directly related or adjacent to product. Some of the most common categories include:

Financial metrics include anything related to money: revenue, sales, margins, operating costs, etc.

The product is a factor here, but far from the only factor. If the product isn’t selling well or making much money, it could be due to poor sales, marketing, content, pricing, and/or product.

Anything related to usage: monthly active users, time spent in app or on site, pages views, churn, abandonment rate, activations, etc.

The product is a major factor, but marketing and sales are also crucial here, as is design.

Quality metrics include performance, bug rates, scalability numbers, reliability, compliance, security, etc. Usability is also something I would consider a quality metric — time to complete a task, for example.

The product is the only factor when it comes to quality metrics.

Are your products having the intended impact on the people using it? If you aim to inform people, are you doing so? If you hope to make people more productive, are they? If your product is designed for entertainment, are your users truly entertained, or just distracted or compelled?

Again, the product is the only factor here.

How do people feel about the product? Would they recommend it?

Net Promoter Score (NPS) is the main metric to track here. Reviews on the app store or TrustPilot are another. Churn rate is important, too. These metrics are mostly product-related but can also be impacted by customer support, customer success, and sales.

A lot goes into sentiment, and product is a major factor, in addition to customer support and success, cost, help content, etc.

Marketing metrics that are relevant to product managers include customer acquisition cost, advertising metrics such as cost per click and click-through rate, all things SEO, conversion rates, etc.

AARRR metrics — also known as pirate metrics because pronouncing them makes you sound like a pirate — are worth calling out because of their notoriety and wide use.

The acronym stands for acquisition, activation, retention (opposite of churn), revenue, and referral. Sometimes you’ll also see this written as AAARRR, with awareness accounting for the extra A.

These metrics are a combination of marketing, financial, usage, and sentiment metrics and represent a funnel. This framework makes sense for many products, but not all.

It’s important to think about the qualities of the metrics themselves so you can know what to do with them. When evaluating metrics, product managers should consider whether they are:

The most basic quality of a metric is whether it’s qualitative or quantitative — that is, is it objectively measurable or is it subjective and self-reported? NPS looks quantitative because it’s a number, but it is also qualitative because it represents sentiment and therefore can fluctuate.

It’s very important to understand the difference between qualitative and quantitative metrics.

If something is quantitative, the next question you should ask is whether or not it is A/B testable.

All quantitative metrics are technically A/B testable, but the experiment may run for a long time to get an answer for some metrics, or you may not have the right infrastructure in place, which could make a metric effectively not A/B testable. If it is efficiently A/B testable, focus can be very tempting, but it isn’t always the right thing.

Again, A/B testing is a critical concept for PMs to understand, so it’s worth taking the time to learn.

A leading indicator is something that can help you figure out when to release. A trailing indicator that you have to wait and see. Most metrics are trailing indicators, which are hard to attribute.

The only metrics that are leading indicators are quality metrics, which makes them very powerful and important to a product manager’s day-to-day.

As with most things in product management, the answer is — drumroll please — it depends!

Let’s start with some super common metrics that are often chosen as key performance indicators (a few metrics that are determined to matter most) or the one metric to rule them all (a single metric that matters more than any other):

We’ll also outline the pluses and minuses of focusing on these metrics from a product perspective.

TLDR; Awareness and involvement are key, but revenue should not be a focus.

Revenue is probably the most common metric product managers are asked to focus on. However, my advice is to avoid focusing on it too intently.

Don’t get me wrong — it makes a lot of sense for sales to zero in on revenue and for it to be a KPI for the company. And the PM should be deeply involved with pricing and sales blockers. But revenue is a trailing indicator and has way too many variables to be useful for product managers to focus on directly.

Another disadvantage of focusing on revenue is that, when it is used as a definition of success, it is then often used for prioritization. And as much as people will pretend they can know how much money a feature will generate, this is not knowable. I’ve seen this approach lead to inflated predictions to get features greenlit.

A final disadvantage is that you may end up forgoing long-term, truly innovative features and products that won’t directly impact revenue, ultimately putting the health of the company at risk.

TLDR: There are good focus options among engagement metrics, but be careful!

I could easily write an entire blog on engagement metrics — this is a deep area that you will undoubtedly immerse in as a PM.

Once again, engagement metrics are trailing indicators of success, which means that improving engagement isn’t necessarily a good thing. It also means that if engagement doesn’t improve, it isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Consider the example of booking a reservation for a restaurant in a maps application. This is a cool feature that both Google Maps and Apple Maps allows you to do. But if people aren’t thinking to use their maps application to decide where to go and instead are focused on getting to where they’ve already decided to go, the initial engagement for such a feature is going to be very low.

This doesn’t mean it was a bad idea or that the feature wasn’t successful; it just means that users need to evolve their thinking about what the maps application is for. They may not ever do this on their own, but with the help of good marketing and the support of other features (such as local guides), this should change over time.

The other canonical example is scrolling on Facebook and Instagram scrolling. There is a point at which continuous scrolling makes people increasingly less happy — the infamous doom scroll. So, if you as a PM are focused on increasing the amount of time spent scrolling the newsfeed, you may be negatively impacting your users.

All that said, used well, engagement metrics are a wonderful thing as long as you are balancing this data with other information (qualitative metrics like NPS or user surveys targeted at your impact metrics). They are quantitative and very often A/B testable, which makes them fun to focus on for the whole team. Pick a couple of engagement metrics very carefully and think about why they may be telling you something different than what you think before you decide on which ones to use.

TLDR: Sentiment metrics are a must-have, but they shouldn’t be used for decision-making or defining success.

A sentiment metric measures how your users feel about your product. Net Promoter Score is the most commonly used sentiment metric, but Superhuman’s product-market fit metric is rivaling NPS in terms of popularity for technology products. NPS measures whether your users would recommend your product. Product-market fit determines how disappointed your users would be if they couldn’t use your product anymore. Sentiment itself is just the beginning.

If you see a drop in NPS, you need to look deeper at what’s behind it. It could be product-related, but it may not be. Doing analysis on the qualitative responses that you receive (for example, including s question at the end such as, “Can you tell us more about why you rated us this way?”) is an essential responsibility of the product manager. But this qualitative data doesn’t necessarily move easily and is definitely not A/B testable, so you shouldn’t focus on it day-to-day.

TLDR; Marketing metrics are great to focus on if you have a concept of conversion in the product.

As a product manager, for the most part, you should understand but not focus on marketing metrics. The exception to this is conversion rate. This is most common if there is something the user literally buys in your product, but could also come into play for a more subtle definition of conversion, such as booking a ride in Uber.

There is overlap here with marketing because if someone comes to your app or site that isn’t the “right” customer, conversion will be low. In this case, it isn’t the product’s fault; it’s marketing’s fault. Or, if the “right” customer comes and they don’t buy anything, the problem may be related to either the supply or the product.

If you have access to them, conversion rates are important to focus on as a PM, in concert with marketing and whoever is in charge of supply.

Impact metrics, in my experience, are not often defined, let alone measured. These are metrics that either qualitatively or quantitatively measure the impact you intend your products to have. If you’re really lucky, a quality metric may double as an impact metric.

For example, in maps, it is knowable whether someone misses a turn. This is a quality metric (clearly bad) and also an impact metric (maps intend to get you to where you are going as efficiently as possible). Or, in search, if a user clicks on a search result immediately, that result is at the top of the list. If they don’t do a subsequent search, you can be pretty darn certain the user found what they were looking for and your search application did what it intended.

Often, though, you are not that lucky. If the user of the Facebook newsfeed spent 20 minutes in a day looking at Facebook, you don’t know if they connected to others at the end of the day. If someone watched a video on YouTube about learning to hula hoop and then spent an hour watching cat videos, you don’t know if that really met their needs that day.

In my case, as I am currently in the business of selling retreats, I don’t know if the user came away feeling transformed. Even if they say they did in a review, I don’t know if that transformation was truly lasting. Impact metrics are designed to address this.

Impact metrics are trailing and mostly not A/B testable (Facebook notably does try to survey users while in the app and uses responses as an A/B). Even so, impact is, in my opinion, the most important metric of all.

I don’t think any of us are building technology just to make money for ourselves and the company; we also want to make a difference in the lives of our users. Whatever that difference is, be it helping them be more productive, more connected, more calm, more entertained, it can be measured through customer interviews and surveys. And knowing that you are improving that impact can be one of the most effective ways to promote collaboration and innovation among your team.

Metrics are a major aspect of being a product manager, but all that data can turn into an endless sea of information if you don’t know how to use it.

As you progress through your product management career, you will naturally continue to develop expertise with metrics. I hope you take away from this guide a few things to add to your toolbox and feel inspired to look more closely at the metrics you are using in your day-to-day roles.

Featured image source: IconScout

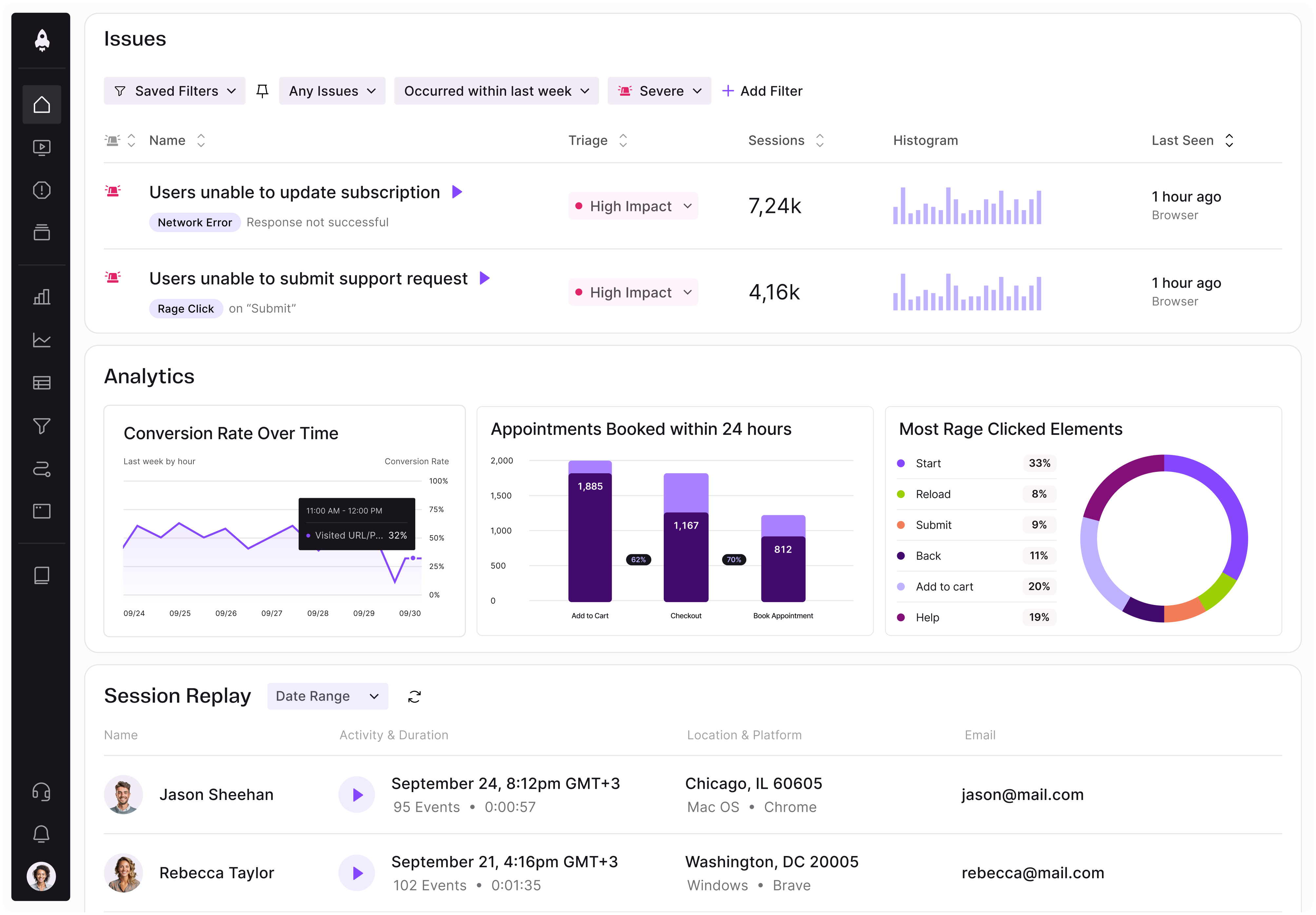

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.