For many teams, both big and small, team members may struggle to estimate the amount of work that needs to be completed, what has already been completed, and how much work is left.

This is where creating a burndown chart comes in handy. To put it simply, a burndown chart is a useful tool to facilitate discussions with your team on the estimated amount of work to complete an initiative or ship a new feature. Once an estimated amount of work is agreed upon, it can be used to manage and organize the work completed in a week. It also helps team members keep track of if work is being completed late or on time.

This article will explain what a burndown chart is and what it does. It will also demonstrate a simple, replicable template on Excel/Google Sheets that anyone can use to start creating their very own burndown chart for any future initiatives or features.

A burndown chart is a simple method to visualize the amount of work completed throughout a sprint or multiple sprints. It tracks whether the actual amount of work completed is pacing well or not against the amount of work that was initially planned for each successive sprint.

This is a very common tool for many agile teams. It helps team members keep track of completed work and what else needs to be done. It’s an effective way to communicate to other internal stakeholders within the company — such as the head of product or CEO of the company — the amount of work your team has completed and how much more time is needed to complete the project.

As a product manager, tracking and managing work via a burndown chart is a shared responsibility with the engineering manager and scrum master of the team. Using such an intuitive visual aid not only helps you organize and plan future work for the team but helps you have a better understanding of the work. In turn, you also gain the ability to communicate that understanding with other stakeholders in the organization who have interest in the progress your team is making.

The main advantages of using a burndown chart are:

Creating a Google Sheets or Excel burndown chart is very easy! We will go through the steps of replicating your own very simple (but useful) Excel burndown chart and you can download a free example on Google Sheets.

Before you even begin putting down anything on a piece of paper, let alone create a burndown chart, you’ll need to have a discussion with the engineering manager and scrum master on the initiative. Where a burndown chart is required, the discussion should focus on fleshing or estimating the following information:

In terms of providing an estimate, different product managers will provide different methods, depending on where and how they work. Personally, I like to keep it simple and utilize story points via Fibonacci sequencing. This is a way of estimating the amount of work that needs to be done to complete a user story. In a Fibonacci sequence, each number is the sum of the previous two in the sequence, e.g. 0,1,1, 2, 3, 5, 8,13, 21, etc.

In my day-to-day, I use the scale up to 13, with 1 being very simple and 13 being very difficult, to estimate the effort required in completing user stories for a sprint. As a product manager, it is important that you have a universal and generally accepted method as a central discussion point.

Having these discussions with the engineering manager and scrum master helps focus engineering leadership on providing realistic timelines on when initiatives will be complete. They also provide you with some degree of confidence that your estimations are, on some level, accurate.

Other than estimating the amount of effort required, other information that might be useful can include:

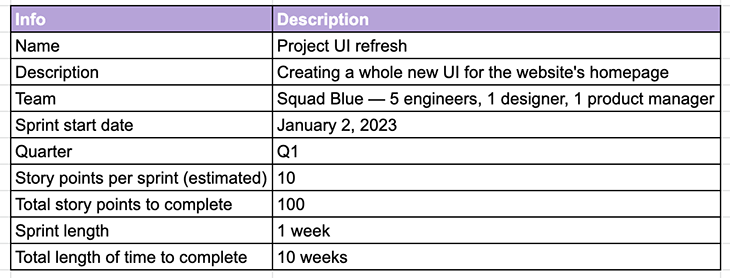

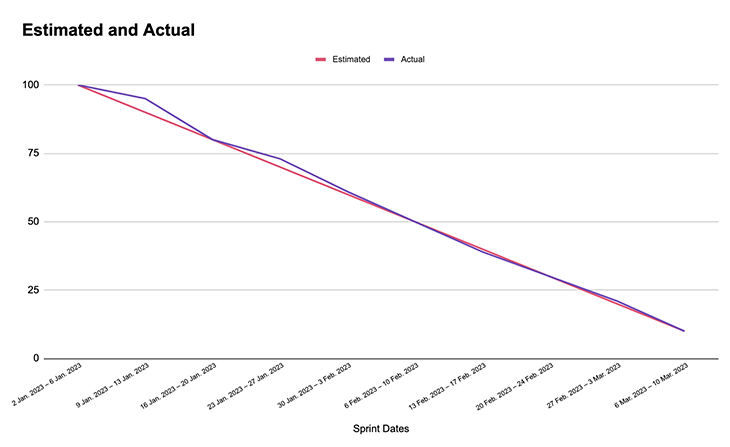

You can see an example below:

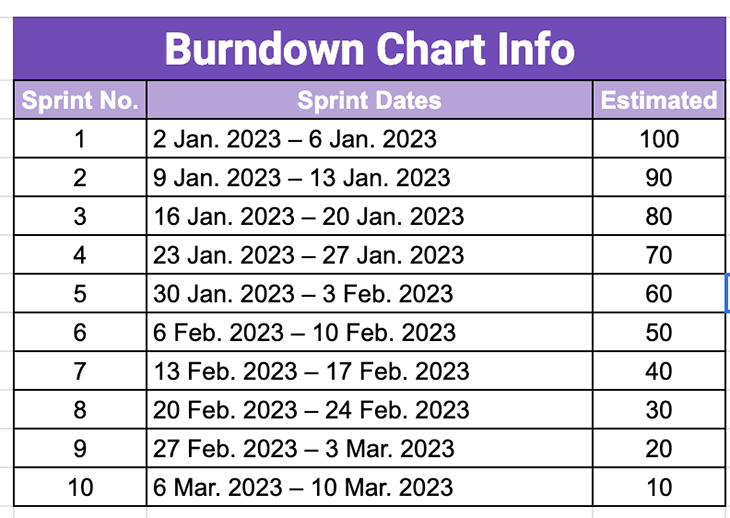

Once a discussion around effort has been held and agreed upon, it’s time to plot out the amount of effort required per sprint. Using the above example table, let’s say it was agreed upon that it would take about 10 weeks (or 10 sprints, if you are using a weekly sprint schedule) to complete the initiative. In total, you’re estimating to take about 100 story points or 10 story points of effort per sprint.

You can then create a table that includes the following information:

See an example below:

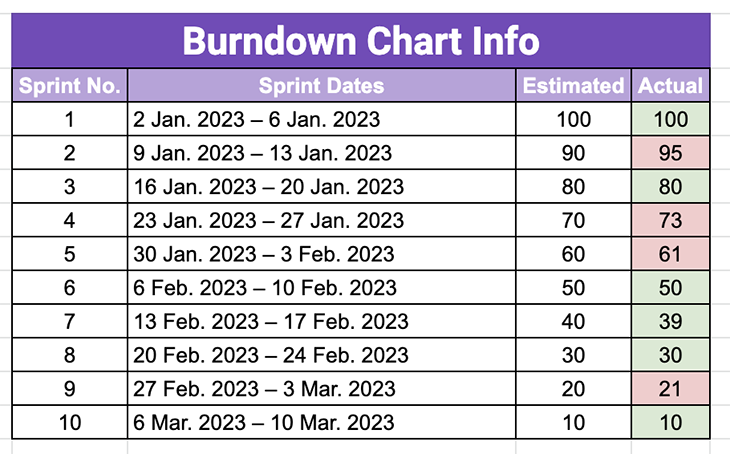

Once you’ve plotted out the estimated amount of effort on a per-week basis, it’s time to kick off the initiative. Every week (or every sprint) as work gets completed, keep track of the amount of finished story points. At the end of every sprint, record the balance of the remaining story points.

Here’s an example of what this looks like:

As seen above, keeping track of story points in the format of a burndown chart helps provide an overview of where the team is either lacking efficiency or is going above and beyond to finish work. This can potentially either move your release date earlier or later than planned.

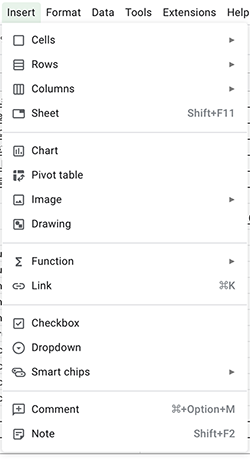

Using the above table, it’s easy to create a chart on Excel or Google Sheets. Start by selecting all of the above data before heading to the top toolbar and selecting Insert > Chart:

When done correctly, you can select the option for Line Chart, which should then create a burndown chart similar to this:

During sprints where the number of user stories or points exhausted is less than budgeted/estimated, it helps you consider if the team is sufficiently staffed or experienced enough to complete the work at hand. It also helps you figure out whether any bottlenecks stopped them from completing the work, or if they require any assistance from you, as the product manager, to help unblock them from their work.

During sprints where the number of user stories or points exhausted is more than budgeted or estimated, it is good to take stock and review to see whether there was something that helped the team achieve greater efficiencies in their work. Can you implement these methods in the following sprints to further achieve greater velocity for the team? Great things to consider!

Please click this link here for a FREE Google Sheets burndown chart template to use for your own teams. It’s pretty self-explanatory, but feel free to reread the article and follow along with the spreadsheet to give you a better understanding!

Use the above instructions and you’ll be able to create your own burndown chart in no time!

If you would like to see other templates that I’ve created for product managers, please feel free to visit this link as well.

Featured image source: IconScout

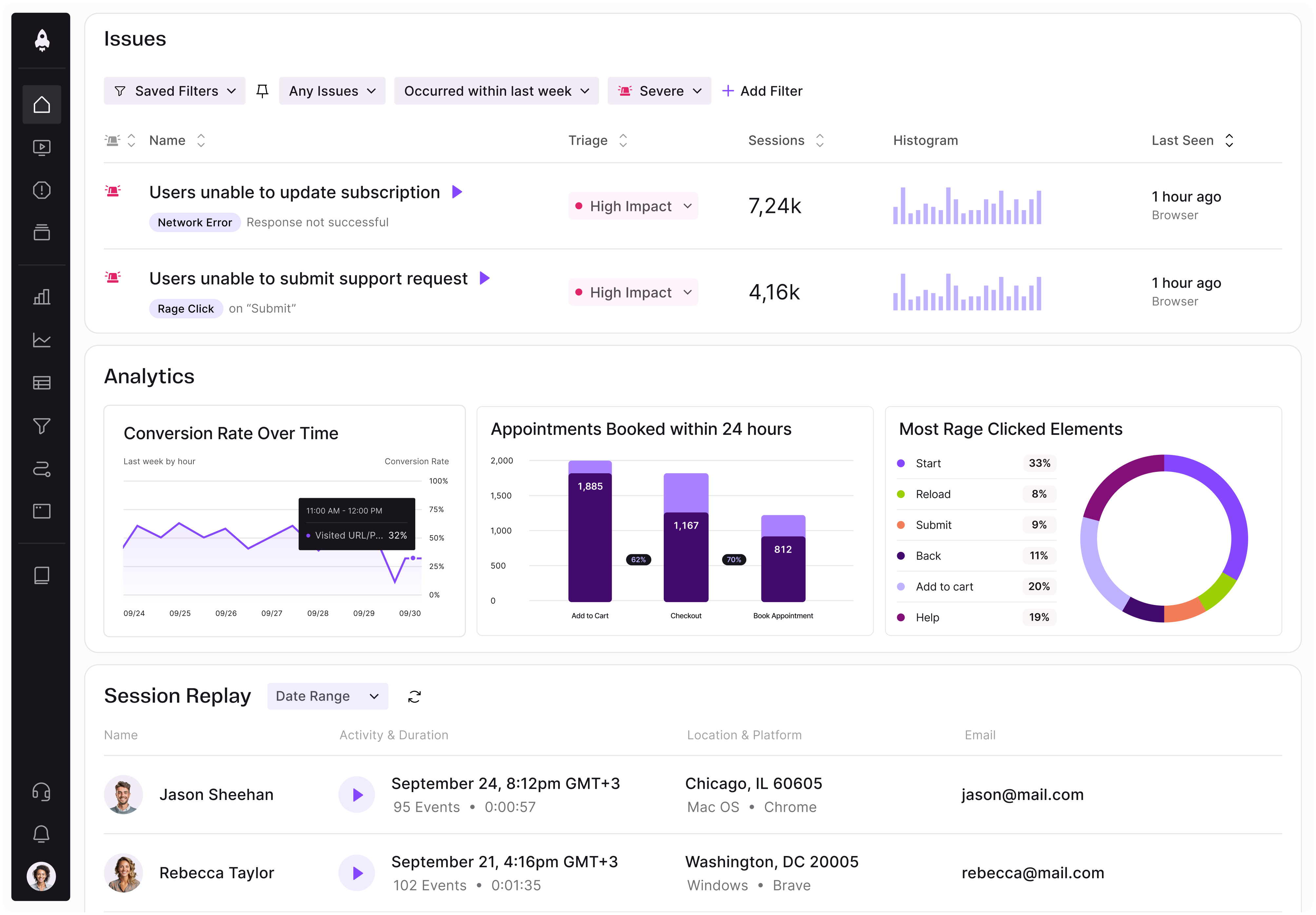

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.

One Reply to "What is a burndown chart?"

This is a good article on using the “burn down” chart method to track progress on projects large enough to use them.

And this approach, along with sprints, works well in many mass manufacturing scenarios.

Speaking from decades of experience both managing software projects and being a hands-on developer/team lead/architect, this is a problematic way to manage software projects.

Software engineering is quite different than manufacturing, though there are some useful commonalities.

Manufacturing is creating N quantity of a single item, assembling it in a deterministic process of known parts and known, repeated, labor processes. There is little that is not predictable. Those who assemble the items are not engineers, but technicians.

Software engineering is creating a number of different items, much of which comes from creating new components or altering existing components. This is nondeterministic, requires creativity, and (most importantly to this article’s context) the time to complete any part of the process is too dependent on a number of variables, as to be predictable.

Software development is best managed by tracking the major milestones (NO SPRINTS), and team leads that know if their team members are being productive or not. Coders are typically not considered creative or professional, but developers, engineers, and architects in software are professionals who are both scientists and artists.

Many software shops have learned that the principles echoed in the “Agile Manifesto” are useful in software engineering, and work when applied to the unique characteristics of each software shop. But many have learned the hard way that using the various “agile methodologies”, especially when managed by non-engineer project managers, are costly, lead to low quality (at best) and failed projects (at worst).

I believe what is presented in this article has some useful principles that, when applied properly, will benefit a software project. Those useful principles do not differ much from how successful software projects were managed before the “agile methodologies” entered the software business, pouring molasses in the gears of success.