Within the field of product management, the Psych framework has emerged as a new tool for understanding a user’s journey with your product. It offers a fresh perspective on conversion funnels and can help you evaluate and optimize conversion rates.

But most importantly, it gives you a quantitative approach to a critical, yet often neglected and ambiguous part of user experience — users’ motivation.

In this article, you will learn what the Psych framework is, the different types of psych, and how you can apply it to your product management.

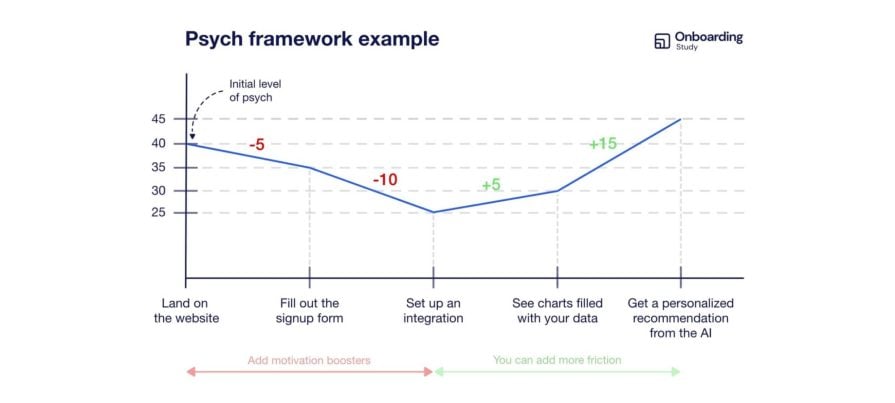

The Psych framework is a conversion rate optimization approach developed by Darius Contractor. Psych begins with the assumption that every user visiting your product or website starts with a particular amount of psych that represents their motivation to complete the product journey. Positive psych increases a user’s motivation to complete the journey, whereas negative psych decreases it.

The most common use case for the Psych framework is to evaluate the whole user journey from start to finish while mapping how each step impacts the overall user psych. From this, you can glean actionable insights as to what potential changes and improvements will maximize the likelihood of a user doing what you want:

To understand the concept better, let’s dive deeper into what exactly constitutes negative and positive psych.

Negative psych comes from actions and elements that decrease users’ motivation by

The most common negative psych elements include:

The more information you ask your users to provide, the more psych energy you consume. People only deal with excessively long governmental documents because of the negative consequences of not filling them.

The harder the decision, the higher the level of remaining psych users must have.

For example, consider that your subscription app offers two different plans:

For each, there are then three different payment options:

In this case, you’re asking users to choose one out of six available options. This creates an extra cognitive effort that could be too much for users with low remaining motivation.

If you don’t ask obvious questions, you’ll force users to consume some of their psych trying to come up with answers.

For example, when setting up HR functions for a company in Gusto, not everyone will necessarily understand how the company’s entity types change or what industry their business fits in, and their desire to figure out this information will rely on the remaining motivation they have.

While negative psych elements borrow fuel from the tank (remaining psych), positive psych elements boost users’ motivation.

The three most common ways to generate positive psych include:

There’s no stronger motivation than human emotions. By understanding your users’ underlying needs and desires, you can craft copy and visuals that address these needs and give users a beacon of hope.

For example, Match.com taps into its users’ emotional need to find a soulmate and surface them by:

This set of small actions creates a powerful first impression and boosts users’ psych to complete next steps.

There are many ways you can boost users’ immediate motivation, that is, motivation to complete the action sooner rather than later. Examples of motivational boosts include:

Implementing a small motivational booster across the whole product experience can have a significant impact on users’ motivation to complete an action as soon as possible.

One of the simplest yet most efficient ways to increase users’ psych is to incentivize them to complete the journey with some sort of reward.

For example, mobile games often offer in-game benefits for leaving App Store reviews. Normally, the motivation to review the app is rather low, but the rewards give users enough of a psych boost to complete the action.

Now that you understand the theory behind the Psych framework, let’s look at how you can implement it with your products.

Start by evaluating every step of the user journey from a psych level perspective.

For example, look at your registration screen and try to find elements that boost motivation to proceed to the next step, as well as ones that create additional friction, and assign them a score. Then, summarize all the positive and negative psych elements to come up with an overall psych level for a given step.

There’s no need to be scientific when it comes to assigning specific numbers. Similar to story point estimations, it’s more about relative comparisons than absolute numbers.

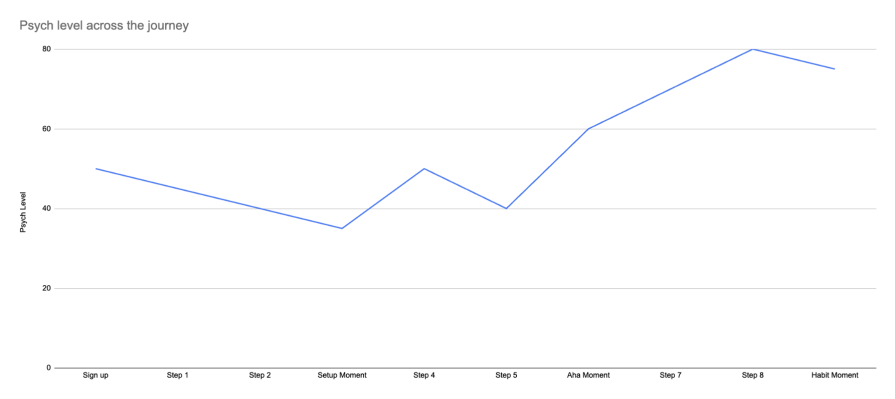

After evaluating each step of your user journey, plot a chart with the psych level your users have after each step:

This representation gives you a clear picture of what boosts user’s motivation, what drains user’s motivation, and what the experience as a whole looks like.

The level of starting psych depends mostly on where the user came from and how motivated they are to complete the journey from the beginning.

For example, if users land on your page mostly from ads, then their initial psych is usually quite low, and the journey must focus on increasing their motivation over time.

On the other hand, users who need to complete a specific journey to collect a reward will have high motivation from the very beginning and you should focus on not allowing their psych level to drop too much.

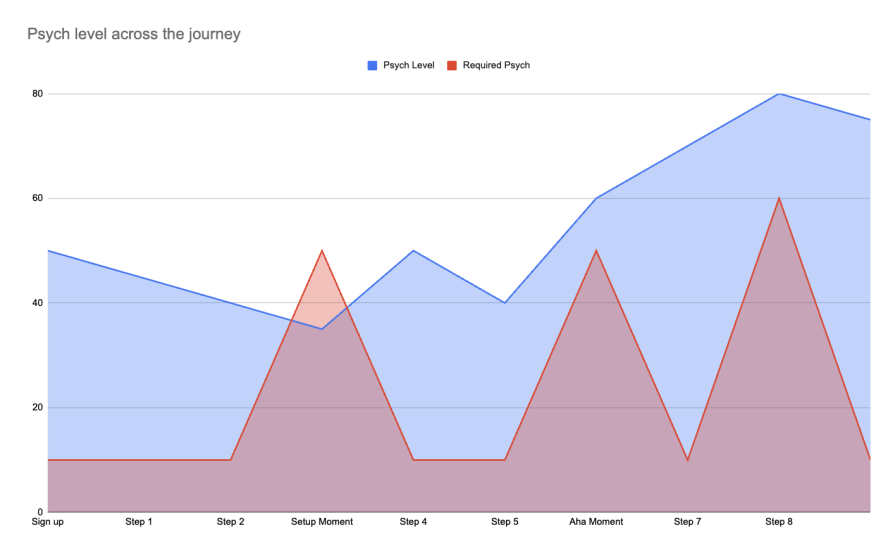

Any task you have for your users not only uses up their psych, but also requires a certain level of psych to be successful.

For example, asking a user to provide an e-mail address doesn’t require much psych. However, asking a user to refer their work colleague to the product or pay a subscription fee is a significantly bigger ask, thus requiring a higher level of psych to begin with.

Identify every task you have for your users across the journey and try to assign it a required psych amount depending on the size of the ask:

You can use your conversion metrics to come to a high-level assessment. If a given step has a below-average conversion rate, you can assume it requires more psych than users currently have on this step.

On the other hand, if the conversion rate on a given step is high, users likely have more psych than the step requires.

This analysis will help you spot which parts of the flow require most of the attention at the given moment.

Now that you have an overall picture of your users’ psych across the user journey, you should start closing the gaps. Most of the optimizations come down to pure UX improvements you need to make, although there are some noteworthy tactics.

One of the basic psych optimization tactics includes changing the order of operation, that is, pushing psych draining/building elements to other parts of the flow.

For example, if you estimate that your setup moment requires 70 psych, and users currently have 60 at this point, you could move some rewards that come later in the flow before the setup moment or try to delay other psych draining fields and ask further down the funnel.

Similar to changing the order of operation, you can also make some psych draining elements optional.

For example, Shopify acknowledges that choosing the name of the store is taxing for many of its users, so it allows them to skip this step and not burn so much psych so early.

If your user journey consists mostly of psych draining parts, there might be some reason for concern. As a rule of thumb, after any serious task, you should give your user some sort of psych boosting reward.

If you leave all the psych boosting parts for the very end, some users might never reach that moment.

Last but not least, religiously optimize user flows for friction. Psych analysis is a great way to mark down even the smallest, often not noticeable, friction points. Scrutinize them and ask yourself:

To be honest, I’m still surprised how many registration forms collect tons of information that isn’t used later in any way.

Although the Psych framework is still relatively fresh and niche, it’s an exciting addition to a product manager’s toolkit.

The framework gives you a quantitative way to measure, observe, and act on users’ motivation. It’s true that the approach is far from scientific and relies mainly on a gut feeling, but over time, it can help you develop a strong sense of how various product changes can impact the likelihood of your users completing your product journey.

Whether you use the Psych framework as a day-to-day user journey planning tool or just as an every-now-and-then audit tool, it can give you a fresh perspective on your user journey that most other frameworks don’t offer.

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.

How AI reshaped product management in 2025 and what PMs must rethink in 2026 to stay effective in a rapidly changing product landscape.