Humans generally don’t like change all that much, opting instead for the comfort of familiarity. However, this can create problems for a product organization because aversion to change is one of the biggest enemies of innovation.

Anything that makes things different than what people are used to will make many people uncomfortable. In an organization, around 15-20 percent of people will be excited about changes, while 20-30 percent will be resistant; the remaining will take a watch-and-see approach.

The question becomes, “How can you innovate in a scenario like this?

That’s where a pilot project comes in. In this article, you’ll learn what a pilot project is, the key elements that go into one, and how you can implement and scale it.

A pilot project is a way of testing something new before deciding upon further investment. Instead of making an entire upfront investment, the pilot project aims to test something on a reduced scale to assess whether it works. When it works, the organization can expand the project; when it doesn’t, it can cut costs.

Some people confuse a pilot project with a proof of concept (POC). However, they’re different. A pilot project represents a real-world scenario, while a POC evaluates whether the team can achieve specific goals.

Pilot projects are helpful to drive change because they aim to start small. When it works well, it’s easy to scale up. Here are a few examples:

A few years ago, I worked for an automaker and one of our struggles was keeping the inventory accurate. We often had problems with missing spare parts. Worse, everyone knew the root cause: Manual work.

We had a system in which whenever someone grabbed a part from the inventory, the person dropped the label in a box. Later, another operator would collect and read the labels, and the system would update the inventory. There were too many failure points in a single process, but changing it entirely would impact hundreds of people, and nobody wanted such a challenge.

That changed once an innovative engineer reimagined how we calculate the inventory. She said, “What if instead of dropping the label in a box, the operator goes through a kind of portal, which automatically reads the labels and sends it to our servers, and voi-là?”

Her idea inspired everyone to try it out, but we had people against it as many uncertainties still lay before us. Setting up a pilot project enabled us to stop talking about the work and start doing it.

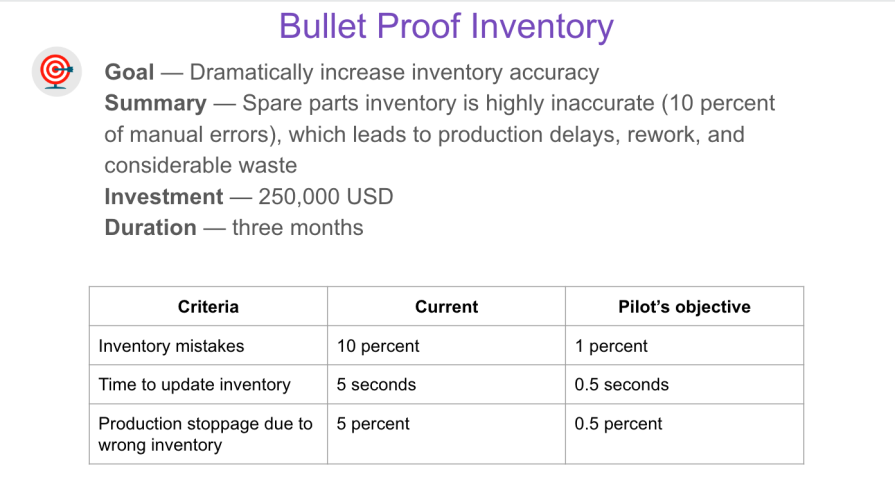

We calculated our investment to change 10 percent of our operations, explore a new solution, and prove we can reduce inventory mistakes from 10 percent to 1 percent. We asked for two months of development time and one month running the pilot.

After getting the greenlights, we explored different solutions and found our way with RFID tags. Within six weeks, we had something to start our pilot. Although our first and second attempts failed, we learned about the issues and could correct the course. Then, we put it into the product and ran it for a month. The results were astounding; we decreased the error by less than a percentage.

The team got excited, and we scaled it up. First, we moved to 20 percent of our operations for another month, then 50 percent, and finally, we went all in.

I attribute the success to starting small with a pilot because it enabled us to pivot the solution when we learned some parts didn’t work. Also, we could observe the operations calmly while collecting real data. The pilot won the skeptical people, enabling us to transform how we managed the production inventory.

At this point though, you might be asking yourself, “How do you gain support to implement a pilot project?”

Let’s take the previous example and break it down to what matters:

When your pilot succeeds, the next natural step is to scale it up. You may think you should just do an immediate rollout, but I’d encourage you to take a step-by-step approach.

Not everything that works with a small sample works with a bigger one. Here are my learnings and recommendations:

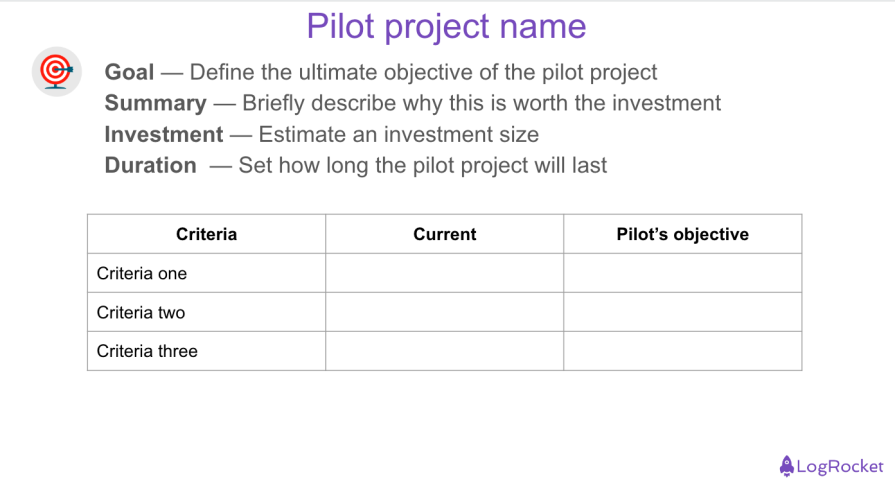

You may wonder how you can pitch your pilot project, given that too many people are resistant to trying new things. Let me simplify that for you with the following template:

Keep it as simple as possible. No business case. No dozens of pages.

You need enough information on a single page that convinces people to learn more about it.

Here are the key parts:

Here’s an example of what we discussed earlier:

Pilot projects are an important tool for helping you win support for complex projects. They aren’t the same as POCs, as they aim to run in production with a reduced sample. Despite the smaller size, they help you determine whether you should scale up or cut costs.

It’s generally a good idea to start as small as possible, while still allowing you to pursue relevant goals. Aim to incrementally deliver value, so that you can prove your need to scale up. Throughout the process, remain laser focused and stay open to learning and adapting from your findings.

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.

How AI reshaped product management in 2025 and what PMs must rethink in 2026 to stay effective in a rapidly changing product landscape.

Deepika Manglani, VP of Product at the LA Times, talks about how she’s bringing the 140-year-old institution into the future.