Dipto Chakravarty is Chief Product Officer at Cloudera, a data cloud platform company. He began his career in software architecture at IBM before moving to Thomson-Reuters and later founding Artersia Technologies, which was acquired by OpenText. Dipto has held engineering leadership positions in companies such as Broadcom/CA, Novell, Exostar, and eSecurity. Prior to joining Cloudera, he served as Head of Local Data Engineering, Artificial General Intelligence at Amazon.

In our conversation, Dipto talks about his ethos that “keeping it simple is hard and making it hard is simple,” i.e., that it takes rigor to simplify complex technology and user experiences, while unintentionally making it harder for users to use is very easy to do. He also discusses strides he’s made to re-vamp user-centric experiences and how he believes product teams can continue on this path.

This is a phrase I coined, and I’ve turned it into a motto of how I work. The one-liner is that “simple” is “complex” resolved. Often, we shift complexity to the back burner if we’re trying to simplify a problem.

For example, in the last decade, technology has become exponentially complex, disrupting software and hardware stacks. Even the tiniest feature of a software or a hardware unit comprises a “system of systems” that work in concert with each other. It’s just like when the jog shuttle came out on the first iPod. Users were asked to just slide their finger over the jog shuttle to make it turn like a wheel, and that controlled the scrolling on the iPod screen. It feels simple to the user, but much complexity is involved behind the scenes to provide that simplified experience.

Keeping things simple has become hard nowadays. It takes discipline and rigor. Conversely, it’s very easy to make things harder. For example, it’s a very common practice in software to just add another layer (like an API) to add complexity. The resulting experience is made up of old plumbing and new plumbing. It might work for a while, but eventually, an incompatibility will cause it to break. There’s a new term called “simplexity” that correctly suggests that finding simple solutions to complex problems is very hard. It’s actually achieved by simplifying complex interfaces into easier, more intuitive interfaces or processes.

This goes back to my point that keeping it simple is hard, while adding another layer is very easy to do — it shows a tactical win in solving a problem. So, I channelize teams’ energy to simplify our product complexity instead of shifting it to another area. When done correctly, the outcome is a happier, simpler user experience. Plus, it creates and delivers value that we can measure as an enriched outcome.

It’s all about balancing data and feedback. And when you don’t have enough data or feedback, use your intuition. Making decisions is an art as much as it is a science.

First, start with the problem, not its solution. Second, triangulate the qualitative and quantitative signals, which I believe are the key tenets to making good decisions successfully. I recommend using data for prioritization and for uncovering patterns, and using feedback for ideation and emotional insight. Last, prioritize data and refine feedback with the voice of the customer in context.

For instance, we often have to make decisions without an ideal amount of data. My advice for times when you have insufficient data is to rely on the anecdotes. This is something that Amazon practices very well. Data and anecdotes may not always agree, but when you have to pick one, go with the anecdotes because they reflect what customers are actually saying.

We over-index on things we are passionate about, even if it’s not the only thing that matters at the time. When this happens, teams go down a path of emotional decision-making. I always say that there are two kinds of decisions: reversible and irreversible.

If we have to make a call on pulling a feature from a release, that’s a two-way door decision, as Amazon calls it. It’s doable and reversible. If something is missed further downstream, we can put it back. We tend to make reversible decisions, such as organizational changes, faster because we can always change things back if necessary. But when it comes to irreversible decisions, we should only make them after taking all the ramifications into account.

I call this “making users the center of the universe.” Focusing on the user ensures we are solving the right problem for the right persona, but it is easier said than done. We often fall more in love with a feature than with the user’s usability challenge.

You have to ruthlessly prioritize to get “curing with design” right. Start with exploratory research. Talk to users and get their feedback on whether something is a roadblock or if it has some type of workaround. That way, you get a general understanding of what you have to do to reduce friction. Next, map the journey so that you can visualize the friction points. Use data to validate and scale insights to understand the feature usage with its micro-behaviors. Get it working in a sandbox and ensure you understand the problem you’ve solved.

Next, work with the user via co-creation. Involve them in rapid prototyping and usability testing to validate that your remedy actually cures their usability problem. The last step is to create a feedback loop so that “curing with design” is iterative and not a one-off process.

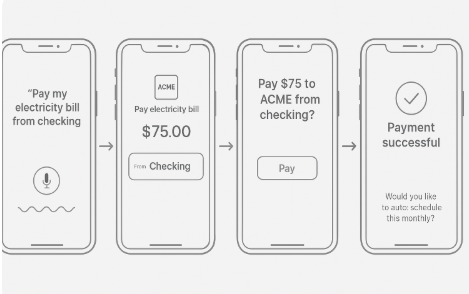

We can use a practical example like voice-activated bill payment in an AI assistant like Amazon’s Alexa. Traditionally, you’d open the payment app, navigate to the bill payment tab, choose how much to pay, select which account it will pull from, hit confirm, authenticate it, and you’re done:

That’s six or seven steps. If you break that design down, though, there are opportunities to reduce the friction. Sure, you can tap the app and enter data, but if you simply say, “Please pay my bill,” with a voice-activated AI assistant, all those seven steps get compressed into one step. It’ll prompt you to authenticate the payment, and all you have to say is, “Yes, this is the amount for this month.” This minimizes cognitive load for the user, reduces steps, and still maintains trust:

| Step | Traditional UI | Simplified with Design (Voice UI) |

| 1. Open app | Tap the app icon | Use voice assistant |

| 2. Navigate to bills | Find the “Bills” tab | No need — context understood |

| 3. Choose payee | Select biller | AI auto-identifies an “electricity” bill |

| 4. Choose account | Drop-down select | Defaults to “checking” based on history |

| 5. Enter amount | Type amount | Defaults to full amount or last paid |

| 6. Confirm | Tap “Pay” | Prompt: “Pay $75 to ACME from checking” |

| 7. Authenticate | FaceID/PIN | Seamless — biometric triggered automatically |

I’d like to see this type of approach taken more often in our industry. Take a step back and re-think user-centric design and development —that’s what new products should be about. A robust mobile app tends to be a very poor experience, yet mobile is how the world interacts. This is why I believe voice-activation through mobile devices is the future. It both authenticates and authorizes in one step, which is not the case for web-based applications.

The first step in my four-step process is to start with the “why.” What are we trying to solve for? The absence of a feature is actually a blessing. In interviews, I often ask, “What features can I not give you that you won’t miss?” The answer reveals how the interviewee thinks and will often determine whether they will become part of my team.

The second step is to focus on use cases, not just feature requests, and the third step is to validate these use cases with data. This is especially important because what users want and what they need are so different. Take Apple, for example. Apple never asked people, “Do you want a phone with a touch keypad?” Do you think users would have said yes? Definitely not.

The last, and fourth, step is to test problems via experimentation and involve designers and UX earlier rather than later. Gone are the days of product development and design being separate. Everything has shifted left — product creation is now under one roof. When you’re learning and discovering user requirements, that’s when designers need to be looped in so they can identify the patterns of how to build the product.

This is a tough one. When we plan, we plan logically — that part is easy. But when we act, we act with emotions, reality, and externality. When you let the problem, not the person, lead product design, discussions get tough at times. Biases creep in. The key is to create a culture of learning by celebrating “micro wins” and then use them as a step function to build trust in data over ego.

A really good example of this is the COVID vaccine appointment experience. That’s something that touched all our lives. At Amazon, our goal was to enable a user to tell their voice assistant their location and ask it to make a vaccine appointment for them. We were ingesting data into the AI pipeline, but there were three adjacent teams each trying to do their part of ingesting, tagging, and indexing the dataset, which resulted in overlapped functionality.

Fortunately, we caught it in time — we recognized the adjacency and were able to de-dup the adjoining functions so that during the final phase, Alexa delivered an enriched experience. Everything was happening so fast, and it was a race against time. In the end, Alexa successfully made vaccine appointments for millions of people. We got amazing feedback from all over the world, including getting mentioned in the Amazon earnings report. Looking back, we innovated at the speed of business because there was a bigger need.

This was a big learning: innovation thrives under constraints. In this case, the constraint was time — we knew we had to succeed, and we put aside all of our emotions. Our North Star goal brought us forward.

I haven’t worked in a team that sits in one location for 20 years — there are always team members in different time zones. Keeping teams focused on the endgame is key. I try to leverage what I call the “cone of productivity.” This is where I get teams to have their rhythm and people to be at a tipping point of their productivity where they are fully productive when they are working on things they thrive on.

To do this, begin with the end in mind and work from right to left. This may sound counterintuitive, but it’s the norm now. If we have a release on a particular date, we have to work backward to set deadlines. There’s always going to be distractions — a teammate leaving, an escalation that derails your work plan, scope creep, etc. We all want our teams to be successful, but the reality is that every team will get distracted by complexity at some point. The key is not to lower the goal to an attainable state just to make the team feel good or let them check the box. Instead, keep the goal high and create an environment of psychological safety around meeting or missing that high bar. This develops innovation muscles that aren’t normally exercised in our daily grind.

Also, I encourage product leaders to drive collaboration, challenge teams, and have them challenge you back. People should feel empowered to make decisions, and from those decisions, we can celebrate what I call “micro wins.”

Work to understand the tradeoff and tipping points between complex and simple, easy and impactful, and good and great product characteristics. And continually remind people about the North Star. That’s how you really build great teams from good teams and great products from good products. Striking a balance between effectiveness and efficiency is the holy grail of the best product makers.

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.