Descriptions of product-market fit (PMF) vary from having a repeatable, sustainable customer acquisition channel (some people want to buy your product) to having customers lining up around the block for it (you’re drowning in demand).

Perhaps more poignant is what it feels like to not have PMF: sales cycles are tediously long, marketing costs are high, you need to throw around unsustainable discounts to get people on board, and your biggest problem is that customers aren’t sticking around.

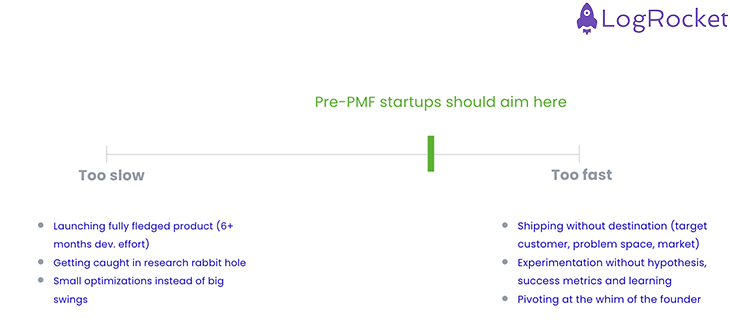

In many startup companies, time before finding product-market fit can be tough — you’re trying to balance ramping up with finding what your customers really need. In this article, we’ll talk about this balance and the dichotomy of being too fast or too slow in a pre-PMF environment.

Life at a pre-PMF startup is incomparable to that in an established business. It’s not about scaling something that works, growth-hacking, or letting network effects do their thing. Instead, it’s about finding your competitive edge, your positioning, your je ne sais quoi that gets your target customer so excited you’ll have to pry your product from their hands.

It’s about trying lots and lots of different things to see what sticks. You operate in a sea of uncertainty, but on the upside, are doing so without a wealth of loyal customers that you might accidentally piss off by taking big risks!

The primary focus of every department, team, and person in your startup should be learning fast and, ideally, everyone is working together to do that.

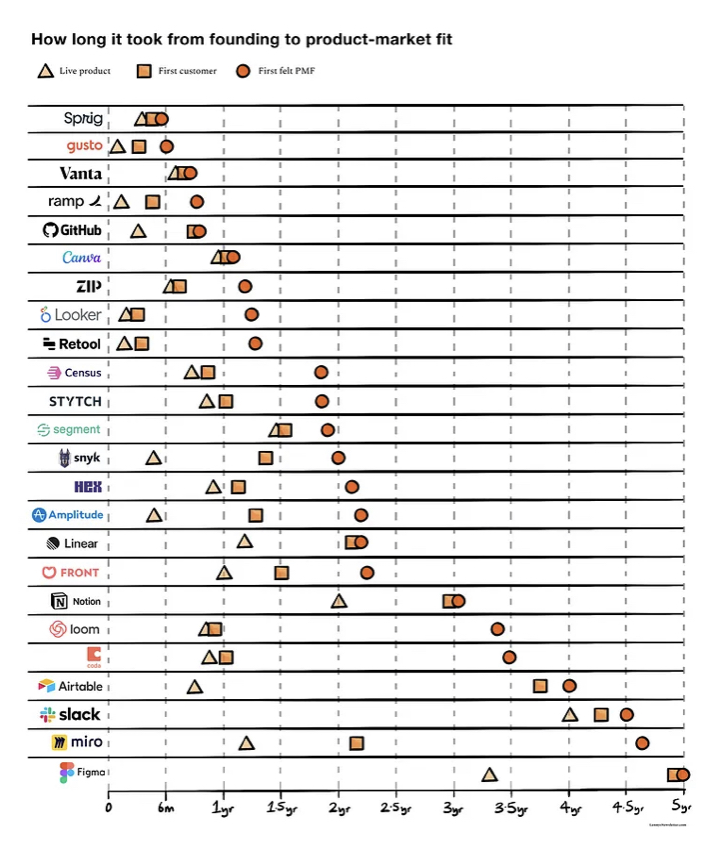

For most successful tech companies, it took time:

If pre-PMF life is all about learning fast, it’s obvious that moving too slow spells startup-death.

Yes, I’m an advocate for doing qualitative research to de-risk development work like customer interviews, shadowing, expert interviews, or usability tests. But I also know that no amount of upfront research will tell you how people will react to your product in the real world!

As David Ogilvy puts it, “The trouble with market research is that people don’t think what they feel, they don’t say what they think and they don’t do what they say.”

To get reliable proof, you need to move from the hypothetical “Would you buy?” to the practical “Will you buy…?” as quickly as possible. Quickly and iteratively shipping small increments of customer value and collecting real-world feedback is the way.

Hiding in your basement and tinkering away at a fully-fledged minimum lovable product, operating in stealth mode, and maintaining secrecy out of fear that your idea will get stolen is not the way.

Here comes the “but.” I’ve seen plenty of startups embrace failing fast — randomly throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what sticks. That doesn’t work.

Here’s what I learned:

This means two things.

Firstly, you need to establish upfront what you’re trying to learn. Formulate a precise and testable hypothesis and your success criteria upfront.

You can steal this hypothesis format:

We believe that if we do […],

[…] will happen,

Because […]

When iterating on a previous test, change only one variable at a time so you can see cause and effect.

Secondly, put in the legwork to understand why something succeeded or failed.

Let’s say you tested your value proposition of locally made, sustainable maternity wear through a marketing fake door test — asking website visitors to sign up for a waitlist. After a significant amount of time, the number of signups turned out…disappointing.

You can a) stubbornly continue, b) switch to something entirely difficult and forget about this painful moment, or c) try to figure out why this value proposition didn’t resonate.

I strongly recommend c), and Matt Lerner’s headline test can help you do it. Here, you ask target prospects who aren’t customers yet to look at your disappointing headline or value proposition. You’ll pull it away after five seconds, without having warned them.

Matt recommends following up with three questions:

Never forget that qualitative research can unlock the “why” behind your quantitative results.

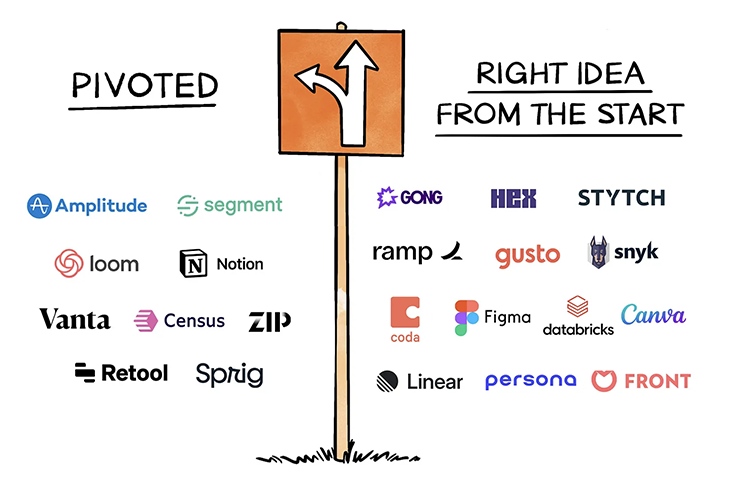

Don’t start your journey without at least a vague destination in mind. That destination can be a specific target customer you want to serve, a market you know well, or a problem you want to solve. If your destination is the product you’d like to build, you’re in for a world of trouble. Your product will likely change many times before finding its PMF form:

Running rapid experiments without such a destination is like playing darts without a dartboard. You can draw a rough outline of your dartboard through market and customer research. There are plenty of industry studies (both paid and free) that can teach you about your market, you can speak with experts (e.g., ex-employees at competitors), and most importantly, you can speak to your audience.

I recommend at least 10 interviews to get you started. You’ll be looking for what’s pushing them away from their current solution, what would pull them toward something new, what anxieties are blocking them from trying that new thing, and what habits they need to break.

If you have fewer than 10 conversations, it’s difficult to detect patterns and generate insights. On the other hand, please don’t get lost down the rabbit hole of customer discovery. Don’t forget to start throwing those darts by shipping a minimum viable solution!

It’s all about balance. Between speed and certainty, between qualitative and quantitative data, and between thinking and doing. Most pre-PMF startups die because they lose their equilibrium.

So, how do we get it right?

“Who’s it for” should be the most important question about any product. You’ll distinguish between your early customer profile — the target customer you will go after first, most likely hallmarked by being relatively easy to reach and acquire — and your ideal customer profile, the target customer you aspire to end up serving:

Most B2B startups dream of serving enterprise customers with mouth-watering LTVs but fail to sell to them for a myriad of reasons. Mainly because of 1) their immaturity and 2) the painfully complex and long sales cycles. By zeroing in on an early customer profile first, you can start moving and keep the lights on.

If “who’s it for” is an afterthought, you have no dartboard and you’re bound to lose your balance. Although I’m all for shipping fast, this question deserves a moment of slowing down and putting in some research work.

Casting a random net around a target audience just to demonstrate that you’re niching down without doing any research (“We target data people at companies with 0–1,000 employees”) is a bad idea. You’ll end up putting your eggs in the wrong basket and missing out on who might have truly benefited from your product.

You should continuously learn and iterate on your initial and ideal customer profile. Your destination may change along the road. With proper ex-post analysis, that’s OK.

Painful truth: you’ll never de-risk an idea entirely through upfront research. I’ve seen PMs who were amazing at established corporations perform poorly at pre-PMF startups because they just couldn’t live with the uncertainty.

In a pre-PMF world, doing 20 customer interviews, 500 surveys, and 10 usability tests is probably overkill. The time and money it took you to take all these steps could have easily been used to put something functional in the market to collect feedback. It’s your job to distinguish whether decisions are business-critical or not so you can gauge how certain you need to be before taking a swing.

I believe that every new product and every new feature requires a business case. If you believe that small new features don’t need a business case because they’re quick to build, you’re missing the point:

I don’t believe in writing 10-page product requirement documents, but I do believe in a one-page-long (maximum two pages) business case that covers the key questions:

It’s not difficult to write a lot of text. The skill is in trimming the fat and writing in clear, human language. Writing down your thoughts helps you detect gaps in your thinking and makes your work transparent to others. If you’re not putting in the effort to write or update a simple business case, you’re likely working without a dart board.

You can steal my product business case template here.

If you can’t test an idea with a minimum viable test, it’s best to discard it immediately.

The difficulty lies in hitting both the minimum and viable benchmarks.

I’ve seen startups spend six-plus months building a fully-fledged platform to test whether their secret sauce resonates. They get caught up in the feature parity game (“Without these 10 features everyone already has, we won’t even be considered in the market!”), and finally find out that no one cares about that special sauce, leaving them with an inferior copy of the market leader’s product.

Six months to start generating real-world learnings is too slow if you’re pre-PMF. You need to cut down your product in smaller increments.

On the other side of the spectrum, it’s useless to go out with a product, marketing, or sales campaign that doesn’t meet the quality threshold to be considered viable by your prospects. You won’t be able to say with certainty that your prospects didn’t like your special sauce if they probably didn’t even consider you.

So how do you strike that balance? Sadly, there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. It’s entirely dependent on your target customer and the market and competitive landscape you’re a part of.

Final words of wisdom — when in doubt, err on the side of moving fast:

Speed is the biggest upper hand you have over the incumbents in your market. Like in Judo, it’s about using the weight of your opponent against them.

Big companies have so much slowing them down:

If you’re not moving fast, you’re missing out on the edge you have over the incumbents you’re up against.

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.

How AI reshaped product management in 2025 and what PMs must rethink in 2026 to stay effective in a rapidly changing product landscape.

Deepika Manglani, VP of Product at the LA Times, talks about how she’s bringing the 140-year-old institution into the future.

Burnout often starts with good intentions. How product managers can stop being the bottleneck and lead with focus.