Editor’s note: This article was last updated on 14 October 2022 to include additional information about React Hooks.

One of the first things you learn when you begin working with React is that you shouldn’t mutate or modify a list:

// This is bad, push modifies the original array items.push(newItem); // This is good, concat doesn’t modify the original array const newItems = items.concat([newItem]);

Despite popular belief, there’s actually nothing wrong with mutating objects. In certain situations, like concurrency, it can become a problem, however, mutating objects is the easiest development approach. Just like most things in programming, it’s a trade-off.

Functional programming and concepts like immutability are popular topics. But in the case of React, immutability isn’t just fashionable, it has some real benefits. In this article, we’ll explore immutability in React, covering what it is and how it works. Let’s get started!

If something is immutable, we cannot change its value or state. Although this may seem like a simple concept, as usual, the devil is in the details.

You can find immutable types in JavaScript itself; the String value type is a good example. If you define a string as follows, you cannot change a character of the string directly:

var str = 'abc';

In JavaScript, strings are not arrays, so you can define one as follows:

str[2] = 'd';

Defining a string using the method below assigns a different string to str:

str = 'abd';

You can even define the str reference as a constant:

const str = 'abc'

Therefore, assigning a new string generates an error. However, this doesn’t relate to immutability. If you want to modify the string value, you have to use manipulation methods like replace(), toUpperCase(), or trim(). All of these methods return new strings; they don’t modify the original one.

It’s important to pay attention to the value type. String values are immutable, but string objects are not.

If an object is immutable, you cannot change its state or the value of its properties. However, this also means that you cannot add new properties to the object.

For example, try the following fiddle:

If you run it, you’ll see an alert window with the message undefined. The new property was not added. Now, try this:

Strings are immutable. The last example creates an object with the String() constructor that wraps the immutable string value. You can add new properties to this wrapper because it’s an object, and it’s not frozen. This example leads us to a concept that is important to understand; the difference between reference and value equality.

With reference equality, you compare object references with either the === and !== operators or the == and != operators. If the references point to the same object, they are considered equal:

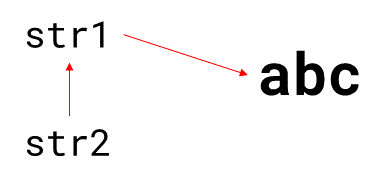

var str1 = ‘abc’; var str2 = str1; str1 === str2 // true

In the example above, both the str1 and str2 references are equal because they point to the same object, 'abc':

Two references are also equal when they refer to the same value if this value is immutable:

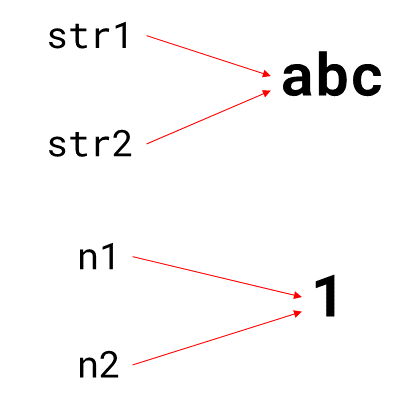

var str1 = ‘abc’; var str2 = ‘abc’; str1 === str2 // true var n1 = 1; var n2 = 1; n1 === n2 // also true

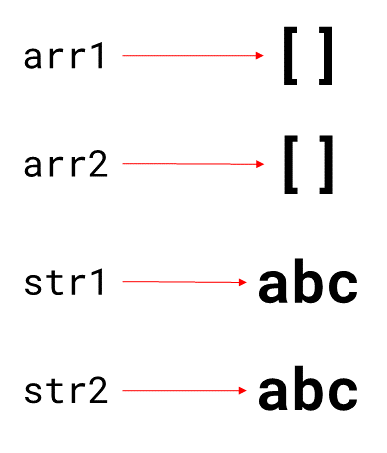

But, when talking about objects, this doesn’t hold true anymore:

var str1 = new String(‘abc’); var str2 = new String(‘abc’); str1 === str2 // false var arr1 = []; var arr2 = []; arr1 === arr2 // false

In each of these cases, two different objects are created, and therefore, their references are not equal:

If you want to check if two objects contain the same value, you have to use value equality, where you compare the values of the properties of the object.

In JavaScript, there’s no direct way to perform value equality on objects and arrays. If you’re working with string objects, you can use the valueOf or trim methods, which return a string value:

var str1 = new String(‘abc’); var str2 = new String(‘abc’); str1.valueOf() === str2.valueOf() // true str1.trim() === str2.trim() // true

For any other type of object, you either have to implement your own equals method or use a third-party library. It’s easier to test if two objects are equal if they are immutable. React takes advantage of this concept to make some performance optimizations; let’s explore these in detail.

React maintains an internal representation of the UI, called the virtual DOM. When either a property or the state of a component changes, the virtual DOM is updated to reflect those changes. Manipulating the virtual DOM is easier and faster because nothing is changed in the UI. Then, React compares the virtual DOM with the version before the update to know what changed, known as the reconciliation process.

Therefore, only the elements that changed are updated in the real DOM. However, sometimes, parts of the DOM are re-rendered even when they didn’t change. In this case, they’re a side effect of other parts that do change. You could implement the shouldComponentUpdate() function to check if the properties or the state really changed, then return true to let React perform the update:

class MyComponent extends Component {

// ...

shouldComponentUpdate(nextProps, nextState) {

if (this.props.myProp !== nextProps.color) {

return true;

}

return false;

}

// ...

}

If the properties and state of the component are immutable objects or values, you can check to see if they changed with a simple equality operator.

From this perspective, immutability removes complexity because sometimes it is hard to know exactly what changed. For example, think about deep fields:

myPackage.sender.address.country.id = 1;

How can you efficiently track which nested object changed? Think about arrays. For two arrays of the same size, the only way to know if they are equal is by comparing each element, which is a costly operation for large arrays.

The most simple solution is to use immutable objects. If the object needs to be updated, you have to create a new object with the new value since the original one is immutable and cannot be changed. You can use reference equality to know that it changed.

The React documentation also suggests treating state as if it were immutable. Directly manipulating the state nullifies React’s state management, resulting in performance issues. The React useState Hook plays a vital role in performance optimization, allowing you to avoid directly manipulating the state in functional components.

To some people, this concept may seem a little inconsistent or opposed to the ideas of performance and simplicity. So, let’s review the options you have to create new objects and implement immutability.

In most real world applications, your state and properties will be objects and arrays. JavaScript provides some methods to create new versions of them.

Object.assignInstead of manually creating an object with the new property, you can use Object.assign to avoid defining the unmodified properties:

const modifyShirt = (shirt, newColor, newSize) => {

return {

id: shirt.id,

desc: shirt.desc,

color: newColor,

size: newSize

};

}

const modifyShirt = (shirt, newColor, newSize) => {

return Object.assign( {}, shirt, {

color: newColor,

size: newSize

});

}

Object.assign will copy all of the properties of the objects passed as parameters, starting from the second parameter to the object specified in the first parameter.

You can use the spread operator with the same effect; the difference is that Object.assign() uses setter methods to assign new values, while the spread operator doesn’t:

const modifyShirt = (shirt, newColor, newSize) => {

return {

...shirt,

color: newColor,

size: newSize

};

}

You can also use the spread operator to create arrays with new values:

const addValue = (arr) => {

return [...arr, 1];

};

concat and slice methodsAlternately, you can use methods like concat or slice, which return a new array without modifying the original one:

const addValue = (arr) => {

return arr.concat([1]);

};

const removeValue = (arr, index) => {

return arr.slice(0, index)

.concat(

arr.slice(index+1)

);

};

In this gist, you’ll see how to combine the spread operator with these methods to avoid mutating arrays while performing common operations.

However, there are two main drawbacks to using these native approaches. For one, they copy properties or elements from one object or array to another, which could be a slow operation for larger objects and arrays. In addition, objects and arrays are mutable by default. There’s nothing that enforces immutability. You have to remember to use one of these methods.

For these reasons, it’s better to use an external library that handles immutability.

The React team recommends Immutable.js and immutability-helper, but you can find many libraries with similar functionality. There are three main types:

Most of these libraries work with persistent data structures.

A persistent data structure creates a new version whenever something is modified, making data immutable while providing access to all versions.

If the data structure is partially persistent, you can access all versions, however, you can only modify the newest version. If the data structure is fully persistent, you can access and modify every version.

Persistent data structures implement new versions in an efficient way based on two concepts, trees and sharing.

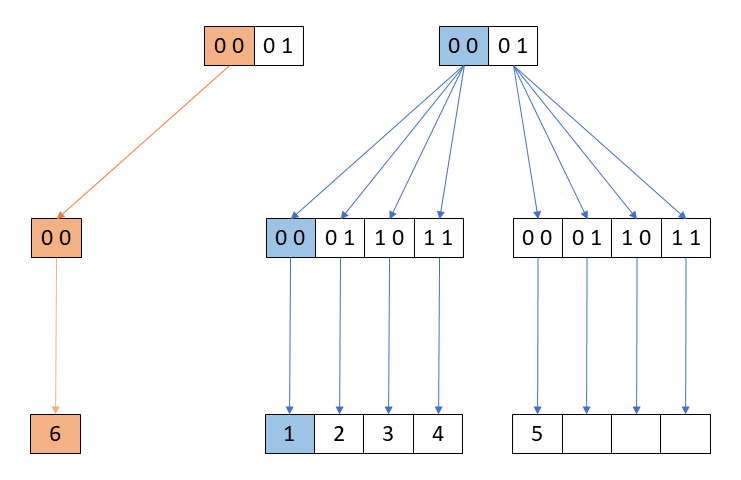

The data structure acts as a list or as a map, but under the hood, it’s implemented as a type of tree, called a trie, specifically a bitmapped vector trie. Only the leaves hold values, and the binary representation of the keys are the inner nodes of the tree.

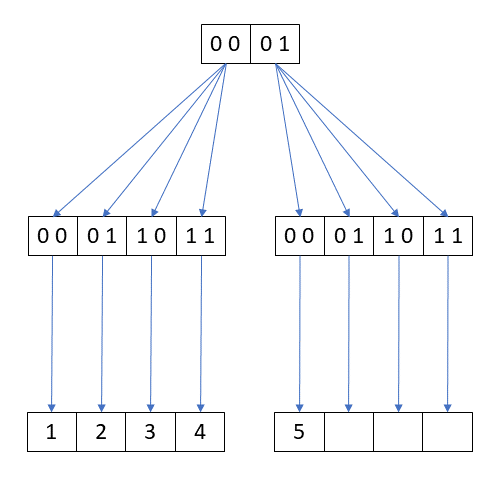

For example, let’s say we have the array below:

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

We can convert the indexes to 4-bits binary numbers:

0: 0000 1: 0001 2: 0010 3: 0011 4: 0100

We can represent the array as a tree as follows:

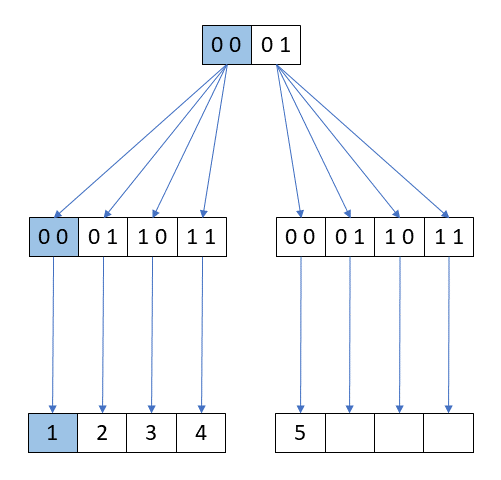

Each level has two bytes that form the path to reach a value. Now, let’s say that you want to update the value 1 to 6:

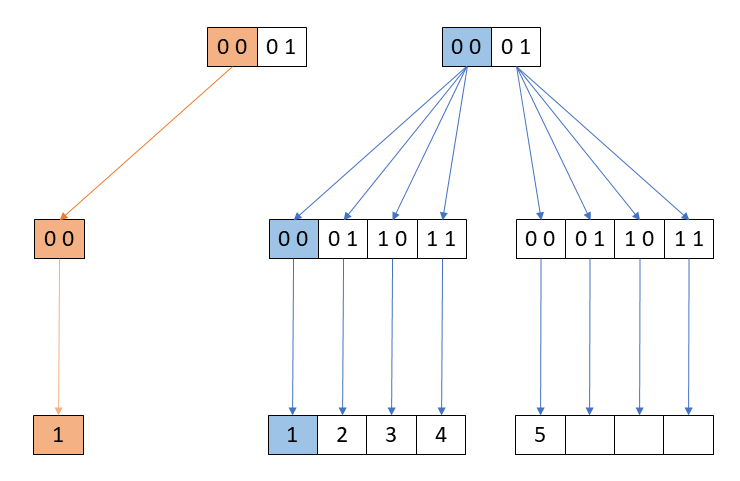

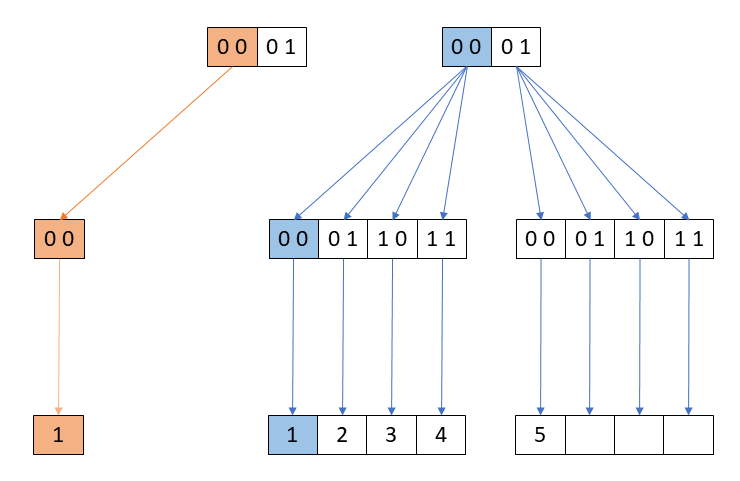

Instead of updating the value in the tree directly, the nodes on the path from the root to the value that you are changing are copied:

The value is updated on the new node:

The rest of the nodes are reused:

In other words, the unmodified nodes are shared by both versions. Of course, this 4-bit branching is not commonly used for these data structures, however, this is the basic concept of structural sharing.

I won’t go into more detail, but if you want to know more about persistent data structures and structural sharing, I recommend reading this article or watching this talk.

Overall, immutability improves your app’s performance and promotes easy debugging. It allows for the simple and inexpensive implementation of sophisticated techniques for detecting changes, and it ensures that the computationally expensive process of updating the DOM is performed only when absolutely necessary.

However, immutability is not without its own problems. As I mentioned before, when working with objects and arrays, you either have to remember to use methods than enforce immutability or use third-party libraries.

Many of these libraries work with their own data types. Although they provide compatible APIs and ways to convert these types to native JavaScript types, you have to be careful when designing your application to avoid high degrees of coupling or harm performance with methods like toJs().

If the library doesn’t implement new data structures, for example, libraries that work by freezing objects, there won’t be any of the benefits of structural sharing. Most likely, objects will be copied when updated, and performance will suffer in some cases.

Additionally, implementing immutability concepts with larger teams can be time-consuming because individual developers must be disciplined, especially when using third-party libraries with steep learning curves. You also have to consider the learning curve associated with these libraries.

Another downside of immutability is seen in Redux, which causes components to render unnecessarily when used in reducers alongside Redux’s combineReducers function. For in-depth knowledge on immutability with Redux, check out immutable data in Redux.

For these reasons, you have to be careful when deciding which method to use to enforce immutability.

Understanding immutability is essential for React developers. An immutable value or object cannot be changed, so every update creates new value, leaving the old one untouched. For example, if your application state is immutable, you can save all the state objects in a single store to easily implement functionality to undo and redo.

Version control systems like Git work in a similar way. Redux is also based on that principle. However, the focus on Redux is more on the side of pure functions and snapshots of the application state. This StackOverflow answer explains the relationship between Redux and immutability in an excellent way.

Immutability has other advantages like avoiding unexpected side effects or reducing coupling, but it also has disadvantages. Remember, as with many things in programming, it’s a trade-off.

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Discover how the Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) keeps your code lean, modular, and maintainable using real-world analogies and practical examples.

<selectedcontent> element improves dropdowns

Learn how to implement an advanced caching layer in a Node.js app using Valkey, a high-performance, Redis-compatible in-memory datastore.

Learn how to properly handle rejected promises in TypeScript using Angular, with tips for retry logic, typed results, and avoiding unhandled exceptions.

5 Replies to "Immutability in React: Should you mutate objects?"

Great post!

Great post

In JavaScript, strings are not arrays so you can do something like this:

str[2] = ‘d’;

But you cannot do this.

Is there a missing “not” in this sentence: “In JavaScript, strings are not arrays so you can do something like this:

str[2] = ‘d’;”

In the above example, both references (str1 and str2) are equal because they point to the same object (‘abc’).

I would change this phrase and also the image it is confusing… because in the end they are not pointing to the same object abc.. they have different values.. so no matter if you change str1 , str2 wont be affected. Because strings are primitive not references.. therefore there;s no pointing.