Editor’s note: This article was last updated on 2 February 2022 to reflect the most recent updates to Firebase.

What do React Hooks and Firebase have in common? They both accelerate development and reduce the amount of code you need to write to build something that would otherwise be complex.

It is actually quite incredible how quickly you can put together a web app with data persistence when you couple the power and simplicity of Firestore with simple and efficient React function components and Hooks. In this article, we’ll learn how to combine Firestore with React Hooks for a simple and efficient grocery list app.

You can jump to a specific part of the tutorial with this table of contents:

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

First, a quick refresher on React Hooks. Hooks allow you to define stateful logic as reusable functions that can be used throughout your React application. Hooks also enable function components to tie into the component lifecycle, previously only possible with class components.

When it comes to creating components that need to handle lifecycle events, React does not prescribe whether you should use function components and Hooks. or more traditional class components.

That being said, function components and Hooks have quickly become a big hit in the React developer community — and with good reason. Function components and Hooks greatly reduce the amount code and verbosity of a React app compared to class components.

Firebase is a collection of services and tools that developers can piece together to quickly create web and mobile applications with advanced capabilities. Firebase services run on top of the Google Cloud Platform, which translates to a high level of reliability and scalability.

Firestore is one of the services included in Firebase. Firestore is a cloud-based, scalable, NoSQL document database. One of its most notable features is its ability to easily stream changes to your data to your web and mobile apps in real time. You will see this in action shortly in a sample app.

Web app development is further accelerated by the Firestore authentication and security rules model. The Firestore web API allows your web app to interact with your Firestore database directly from the browser without requiring server-side configuration or code. It’s literally as simple as setting up a Firebase project, integrating the API into client-side JavaScript code, and then reading and writing data.

React function components, Hooks, and the Firestore web API complement each other incredibly well. It’s time to see all of these in action. Let’s take a look at an example grocery list web app and some of its code.

To explore using React Hooks with Firebase, we need some sample code. Let’s use the grocery list web app as an example.

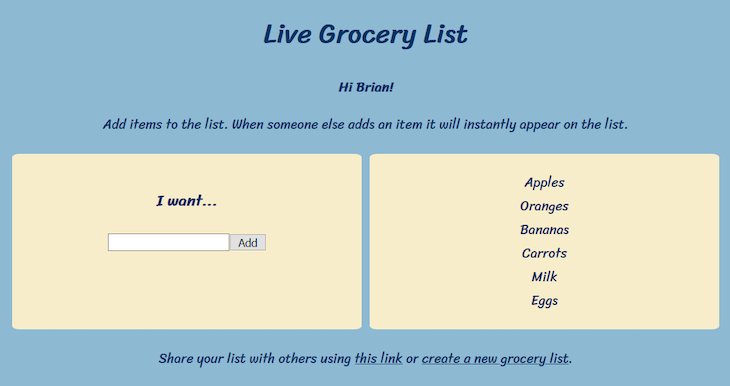

You can try the grocery list web app for yourself. Please ignore the CSS styles resurrected from a 1990s website graveyard — UI design is clearly not my strong suit.

If you haven’t tried the app out yet, you might be wondering how it works. Essentially, it allows you to create a new grocery list. The grocery list’s URL can be shared with other users, who can then join the list and add their own grocery items.

Grocery list items immediately appear on the screen as they are added to the database. This creates a shared experience, where multiple users can add items to the list at the same time and see each other’s additions.

The grocery list web app is built completely using React function components and Hooks. Grocery list and user data is persisted to Firestore. The web app itself is hosted using Firebase hosting.

Full source code for the grocery list app is available on GitHub in this repository.

All calls to the Firebase web API to retrieve or update data on Firestore have been grouped together in src/services/firestore.js. At the top of this file, you will see Firebase app initialization code that looks like this:

const firebaseConfig = {

apiKey: process.env.REACT_APP_FIREBASE_API_KEY,

authDomain: process.env.REACT_APP_FIREBASE_AUTH_DOMAIN,

projectId: process.env.REACT_APP_FIREBASE_PROJECT_ID

};

const app = initializeApp(firebaseConfig);

const db = getFirestore(app)

In the modular Firebase SDK, functions are imported independently from their respective modules, and not chained from a namespace as they were in Firebase v8. You will notice this in how initializeApp and getFirestore are used.

In order to use Firebase services, you must provide some configuration to the initializeApp function, and initialize an instance of the service you want to use (in this case, Firestore). Every service requires a different function for its initialization, and for Firestore, it is getFirestore.

The configuration you are required to provide to the initializeApp function depends on which Firebase services you are using. In this case, I am only using Firestore, so an API key, authentication domain, and project ID are all that is required. Once you have created a Firebase project and added a web app, your unique configuration settings can be found on the General tab of the project’s settings screen on the Firebase console.

At first glance, the Firebase configuration settings seem as though they should be private and not exposed in the browser. That is not the case, though; they are safe to include in your client-side JavaScript. Your application is secured using Firebase authentication and Firestore security rules. I won’t get into those details, but you can read more about it here.

You may have also noticed that I replaced configuration values with React environment variables defined on the global process.env object. You probably don’t want to include this configuration in your source code repository, especially if your repository is publicly available and intended to be shared and cloned by other developers.

Developers are bound to download your code and run it without realizing they are consuming your Firebase resources. Instead, I have opted to include a sample .env file that documents the configuration settings that must be provided before running the app. When I am running the app myself locally, I have my own .env.local file that doesn’t get checked into source control.

Once your Firebase configuration has been set up, getting started with writing and reading data from your Firestore database requires very little code.

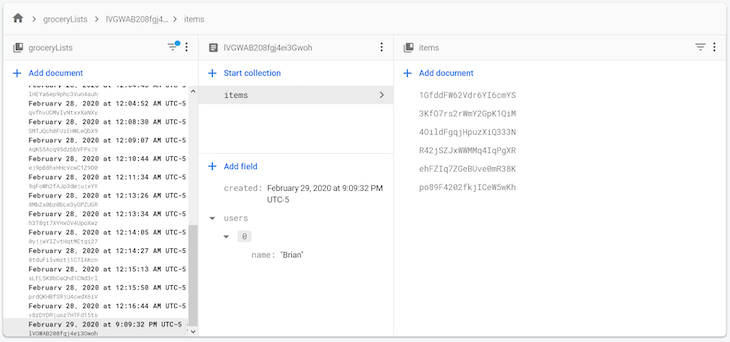

In its basic form, a Firestore database consists of collections of documents. A document can contain multiple fields of varying types, including a sub-collection type that allows you to nest document collections. All of this structure is generated on the fly as your JavaScript code makes calls to the Firebase API to write data.

The functions for writing data to Firestore are setDoc and addDoc. Both functions do the same thing behind the scenes, but the difference is how they are used. When you use setDoc to create a document, you must specify an ID for the document, while for addDoc, Firestore auto-generates an ID for you when the collection reference and document’s data is provided.

For example, the following code creates a new grocery list document in the groceryLists collection using addDoc:

export const createGroceryList = (userName) => {

const groceriesColRef = collection(db, 'groceryLists')

return addDoc(groceriesColRef, {

created: serverTimestamp(),

users: [{ name: userName }]

});

};

You can find an example on how to use setDoc here.

With the above code, when a grocery list document is created, I store the name of the user creating the list and a timestamp for when the list was created. When the user adds their first item to the list, an items sub-collection is created in the document to hold items on the grocery list.

The Firebase console’s database screen does a great job visualizing how your collections and documents are structured in Firestore.

Next, let’s look at how grocery list data is stored in React component state.

React components can have state. Prior to Hooks, if you wanted to use the React state API, your React components had to be class components. Now you can create a function component that uses the built-in useState Hook.

In the grocery list web app, you’ll find an example of this in the App component:

function App() {

const [user, setUser] = useState()

const [groceryList, setGroceryList] = useState();

The App component is the top-level component in the React component hierarchy of the grocery list web app. It holds on to the current user and grocery list in its state, and shares the parts of that state with child components as necessary.

The useState Hook is fairly straightforward to understand and use. It accepts an optional parameter that defines the initial state to be used when an instance of the component is mounted (or, in other words, initialized).

It returns a pair of values, for which I have used destructuring assignment to create two local variables. For example, user lets the component access the current user state, which happens to be a string containing the user’s name. Then the setUser variable is a function that is used to update the user state with a new user name.

OK, great — the useState Hook lets us add state to our function components. Let’s go a little a deeper and look at how we can load an existing grocery list object from Firestore into the App component’s state as a side effect.

When a link to a grocery list is shared with another user, that link’s URL identifies the grocery list using the listId query parameter. We will take a look at how we access that query parameter later, but first we want to see how to use it to load an existing grocery list from Firestore when the App component mounts.

Fetching data from the backend is a good example of a component side effect. This is where the built-in useEffect Hook comes into play. The useEffect Hook tells React to perform some action or “side effect” after a component has been rendered in the browser.

I want the App component to load first, fetch grocery list data from Firestore, and only display that data once it is available. This way, the user quickly sees something in the browser even if the Firestore call happens to be slow. This approach goes a long way toward improving the user’s perception of how fast the app loads in the browser.

Here is what the useEffect Hook looks like in the App component:

useEffect(() => {

if (groceryListId) {

FirestoreService.getGroceryList(groceryListId)

.then(groceryList => {

if (groceryList.exists) {

setError(null);

setGroceryList(groceryList.data());

} else {

setError('grocery-list-not-found');

setGroceryListId();

}

})

.catch(() => setError('grocery-list-get-fail'));

}

}, [groceryListId, setGroceryListId]);

The useEffect Hook accepts two parameters. The first is a function that accepts no parameters and defines what the side effect actually does. I am using the getGroceryList function from the firestore.js script to wrap the call to the Firebase API to retrieve the grocery list object from Firestore.

The Firebase API returns a promise that resolves a DocumentSnapshot object that may or may not contain the grocery list depending on whether the list was found. If the promise rejects, I store an error code in the component’s state, which ultimately results in a friendly error message displayed on the screen.

The second parameter is an array of dependencies. Any props or state variables that are used in the function from the first parameter need to be listed as dependencies.

The side effect we just looked at loads a single instance of a document from Firestore, but what if we want to stream all changes to a document as it changes?

React class components provide access to various lifecycle functions, like componentDidMount and componentWillUnmount. These functions are necessary if you want to do something like subscribe to a data stream returned from the Firestore web API after the component is mounted and unsubscribe (clean up) just before the component is unmounted.

This same functionality is possible in React function components with the useEffect Hook, which can optionally return a cleanup function that mimics componentWillUnmount.

Let’s look at the side effect in the Itemlist component as an example:

useEffect(() => {

const unsubscribe = FirestoreService.streamGroceryListItems(groceryListId,

(querySnapshot) => {

const updatedGroceryItems =

querySnapshot.docs.map(docSnapshot => docSnapshot.data());

setGroceryItems(updatedGroceryItems);

},

(error) => setError('grocery-list-item-get-fail')

);

return unsubscribe;

}, [groceryListId, setGroceryItems]);

The streamGrocerylistItems function is used to stream changes to the items sub-collection of a grocery list document as the data changes on Firestore. It takes in two callbacks and returns an unsubscribe function.

The first callback will contain a querySnapshot, which is an array of documents listened to in the items sub-collection. It updates each time document’s within the items sub-collection changes, and the second callback is used to handle listen errors.

The unsubscribe function can be returned as is from the effect to stop streaming data from Firestore just before the ItemList component is unmounted. For example, when the user clicks the link to create a new grocery list, I want to stop the stream before displaying the “create grocery list” scene.

Let’s take a closer look at the streamGrocerylistItems function:

export const streamGroceryListItems = (groceryListId, snapshot, error) => {

const itemsColRef = collection(db, 'groceryLists', groceryListId, 'items')

const itemsQuery = query(itemsColRef, orderBy('created'))

return onSnapshot(itemsQuery, snapshot, error);

};

The function here that does the data streaming in real time is onSnapshot. It can either receive a query, collection, or document reference of the document you wish to stream as its first parameter.

In this case, I am passing itemsQuery, which has reference to the items sub-collection. The other parameters I passed are the callbacks we mentioned earlier, which then returns an unsubscribe function used to stop the streaming. You can learn more about how real time streaming works here.

Next, let’s look at how we can create a custom Hook to encapsulate some shared state and logic.

We want the grocery list app to use the list ID query parameter and react to changes. This is a great opportunity for a custom Hook that encapsulates the grocery list ID state and keeps it in sync with the value of the query parameter.

Here is the custom Hook:

function useQueryString(key) {

const [ paramValue, setParamValue ] = useState(getQueryParamValue(key));

const onSetValue = useCallback(

newValue => {

setParamValue(newValue);

updateQueryStringWithoutReload(newValue ? `${key}=${newValue}` : '');

},

[key, setParamValue]

);

function getQueryParamValue(key) {

return new URLSearchParams(window.location.search).get(key);

}

function updateQueryStringWithoutReload(queryString) {

const { protocol, host, pathname } = window.location;

const newUrl = `${protocol}//${host}${pathname}?${queryString}`;

window.history.pushState({ path: newUrl }, '', newUrl);

}

return [paramValue, onSetValue];

}

I have designed useQueryString as a generic Hook that can be reused to link together any state with any query parameter and keep the two in sync. The Hook has two internal functions that are used to get and set the query string parameter.

The getQueryParamValue function accepts the parameter’s name and retrieves its value. The updateQueryStringWithoutReload uses the History API to update the parameter’s value without causing the browser to reload. This is important because we want a seamless user experience without full page reloads when a new grocery list is created.

I use the useState Hook to store the grocery list ID in the Hook’s state. I return this state from the Hook in a way similar to how the built-in useState Hook works. However, instead of returning the standard setParamValue function, I return onSetValue, which acts as an interceptor that should only be called when the value of the state changes.

The onSetValue function itself is an instance of the built-in useCallback Hook. The useCallback Hook returns a memoized function that only gets called if one of its dependencies changes. Any props or state variables that are used by a useCallback hook must be included in the dependency array provided in the second parameter passed when creating the hook.

The end result is a custom Hook that initially sets its state based on a query parameter and updates that parameter when the state changes.

The useQueryParameter Hook is a highly reusable custom Hook. I can reuse it later on if I want to define a new type of state that I want to store in URL query string. The only caveat is that the state needs to be a primitive data type that can be converted to and from a string.

We have explored a few of the built-in React Hooks, such as useState, useEffect, and useCallback, but there are still others that could help you as you build your application. The React documentation covers all the built-in Hooks very clearly.

We have explored some of the Firebase web APIs that let you create, retrieve, and stream data from Firestore, but there are many other things you can do with the API. Try exploring the Firestore SDK documentation for yourself.

There are plenty of improvements that can be made to the grocery list web app, too. Try downloading the source code from GitHub and running it yourself. Don’t forget that you will need to create your own Firebase project and populate the .env file first before running the app. Clone or fork the repo and have fun with it!

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Discover five practical ways to scale knowledge sharing across engineering teams and reduce onboarding time, bottlenecks, and lost context.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 4th issue.

Paige, Jack, Paul, and Noel dig into the biggest shifts reshaping web development right now, from OpenClaw’s foundation move to AI-powered browsers and the growing mental load of agent-driven workflows.

Check out alternatives to the Headless UI library to find unstyled components to optimize your website’s performance without compromising your design.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

9 Replies to "How to use React Hooks with Firebase Firestore"

Hi. Thanks for sharing.

I use React-Redux-Firebase for this purpose.

You could easily improve your CSS by changing the background to different color and removing italics and using some modern, good font like Open Sans. Thank you for the tut BTW!

Agreed! Thanks for the tip!

thanks for sharing and for the clear explanation!

I really enjoyed this blog post and the example was great. I have been experimenting with Recoil for state management so I forked your repo and did a build that uses Recoil instead of passing props around. If anyone is interested in looking at it or providing comments the repo is here: https://github.com/findmory/firebase-with-react-hooks/tree/recoil

Oh cool, I haven’t heard of Recoil before you but you just gave me a good excuse to try it out. Thanks!

great explanation! thank you!

Having a hard time following where you’re creating your item sub collection. I don’t see it listed in the addDoc, where is it written in code to add a new subcollection into a new document?

When I use addDoc Firestore, when user refreshed the browser, it cancelled that request. What do you think. I want finding to handle pending state.