The virtual DOM is a fundamental React concept; if you’ve written any React code within the last few years, you’ve probably heard of it. However, you might not understand how it works and why React uses it.

In this article, we’ll define the characteristics of the virtual document object model (DOM), explore its benefits in React, and review a practical example. Let’s get started!

The virtual DOM is a lightweight, memory-based representation of the real DOM that enables React to update user interfaces by calculating the minimal set of changes needed. When a component’s state changes, React creates a new virtual DOM and then compares it with the previous version using a diffing algorithm.

It then updates only the parts of the real DOM that have actually changed. This makes for a better user experience because it reduces the number of direct manipulations to the browser’s DOM.

Editor’s note: This post was updated in March 2025 by Muhammed Ali to include a clear and succinct definition of the virtual DOM, information on how the virtual DOM works, and the benefits/pitfalls of using the virtual DOM.

The virtual DOM works in three main steps:

When a component’s state or props change, React re-renders the component to generate a new virtual DOM tree. This tree is a representation of the UI composed of plain JavaScript objects. It mirrors the structure of the actual DOM elements but omits browser details, making it quick to create and update without direct interaction with the real DOM.

Once the new virtual DOM tree is created, React performs a diffing process. It compares the new tree with the previous version to identify exactly which elements have changed. This comparison matches element types using keys for list items to quickly pinpoint modifications. By isolating only the differences, React significantly minimizes the number of updates needed.

After determining the differences, React generates a set of minimal update instructions and applies these changes to the actual DOM. This process is known as patching.

Instead of re-rendering the entire DOM tree, only the modified parts are updated. This selective updating reduces the performance overhead associated with full DOM updates. This will mean that the user interface remains fast even as the application grows in complexity.

DOM operations are very fast, light operations. However, when the app data changes and triggers an update, re-rendering can be expensive.

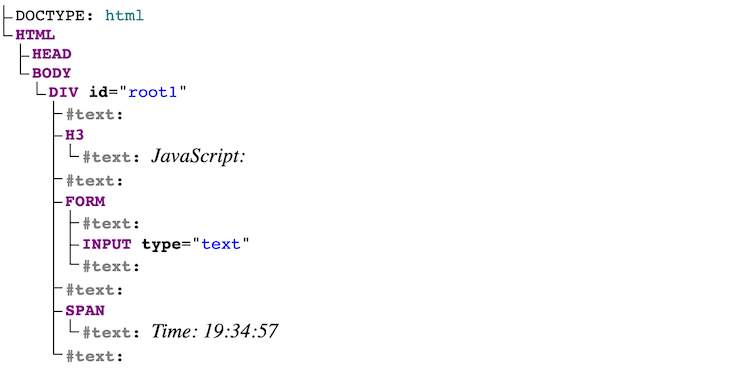

Let’s simulate re-rendering a page with the JavaScript code below:

const update = () => {

const element = `

<h3>JavaScript:</h3>

<form>

<input type="text"/>

</form>

<span>Time: ${new Date().toLocaleTimeString()}</span>

`;

document.getElementById("root1").innerHTML = element;

};

setInterval(update, 1000);

You can find the complete code on CodeSandbox. The DOM tree representing the document looks like the following:

The setInterval() callback in the code lets us trigger a simulated re-render of the UI after every second. As seen in the GIF below, the document DOM elements are rebuilt and repainted on each update. The text input in the UI also loses its state due to this re-rendering:

As seen above, the text field loses the input value when an update occurs in the UI, which calls for optimization.

Different JavaScript frameworks offer different solutions and strategies to optimize re-rendering. However, React implements the concept of the virtual DOM.

As the name implies, the virtual DOM is a much lighter replica of the actual DOM in the form of objects. The virtual DOM can be saved in the browser memory and doesn’t directly change what is shown on the user’s browser. Implemented by several other frontend frameworks, like Vue, React’s declarative approach is unique.

Here’s what to consider when contemplating use of the virtual DOM in React:

A common misconception is that the virtual DOM is faster than or rivals the actual DOM. However, this is untrue.

In fact, the virtual DOM’s operations support and add on to those of the actual DOM. Essentially, the virtual DOM provides a mechanism that allows the actual DOM to compute minimal DOM operations when re-rendering the UI.

For example, when an element in the real DOM is changed, the DOM will re-render the element and all of its children. When it comes to building complex web applications with a lot of interactivity and state changes, this approach is slow and inefficient.

Instead, in the rendering process, React employs the concept of the virtual DOM, which conforms with its declarative approach. Therefore, we can specify what state we want the UI to be in, after which React makes it happen.

After the virtual DOM is updated, React compares it to a snapshot of the virtual DOM taken just before the update, determines what element was changed, and then updates only that element on the real DOM. This is one method the virtual DOM employs to optimize performance. We’ll go into more detail later.

The virtual DOM abstracts manual DOM manipulations away from the developer, helping us to write more predictable and unruffled code so that we can focus on creating components.

Thanks to the virtual DOM, you don’t have to worry about state transitions. Once you update the state, React ensures that the DOM matches that state. For instance, in our last example, React ensures that on every re-render, only Time gets updated in the actual DOM. Therefore, we won’t lose the value of the input field while the UI update happens.

Let’s consider the following render code representing the React version of our previous JavaScript example:

// ...

const update = () => {

const element = (

<>

<h3>React:</h3>

<form>

<input type="text" />

</form>

<span>Time: {new Date().toLocaleTimeString()}</span>

</>

);

root.render(element);

};

For brevity, we have removed some of the code. You can see the complete code on CodeSandbox. We can also write JSX code in plain React, as follows:

const element = React.createElement(

React.Fragment,

null,

React.createElement("h3", null, "React:"),

React.createElement(

"form",

null,

React.createElement("input", {

type: "text"

})

),

React.createElement("span", null, "Time: ", new Date().toLocaleTimeString())

);

Keep in mind that you can get the React equivalent of JSX code by pasting the JSX elements in a Babel REPL editor.

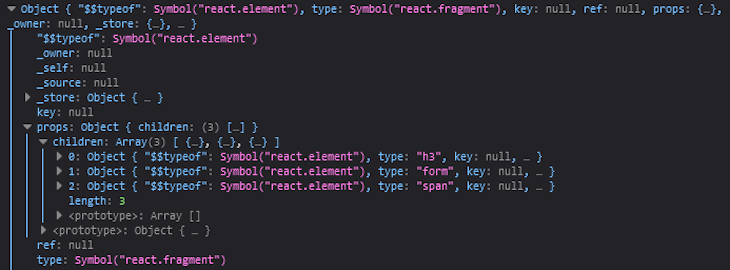

Now, if we log the React element in the console, we’ll end up with something like in the following image:

const element = (

<>

<h3>React:</h3>

<form>

<input type="text" />

</form>

<span>Time: {new Date().toLocaleTimeString()}</span>

</>

);

console.log(element)

The object, as seen above, is the virtual DOM. It represents the user interface.

To understand the virtual DOM strategy, we need to understand the two major phases that are involved: rendering and reconciliation.

When we render an application user interface, React creates a virtual DOM tree representing that UI and stores it in memory. On the next update, or in other words, when the data that renders the app changes, React will automatically create a new virtual DOM tree for the update.

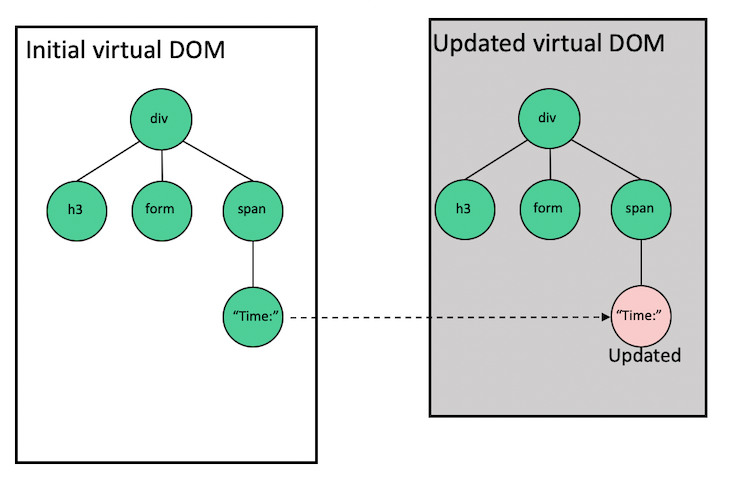

To further explain this, we can visually represent the virtual DOM as follows:

The image on the left is the initial render. As the Time changes, React creates a new tree with the updated node, as seen on the right side.

Remember, the virtual DOM is just an object representing the UI, so nothing gets drawn on the screen.

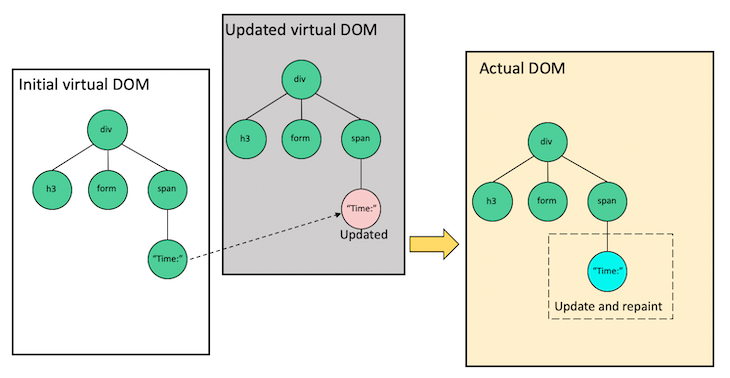

After React creates the new virtual DOM tree, it compares it to the previous snapshot using a diffing algorithm called reconciliation to figure out what changes are necessary.

After the reconciliation process, React uses a renderer library like ReactDOM, which takes the different information to update the rendered app. This library ensures that the actual DOM only receives and repaints the updated node or nodes:

As seen in the image above, only the node whose data changes gets repainted in the actual DOM. The GIF below further proves this statement:

When a state change occurs in the UI, we’re not losing the input value.

In summary, on every render, React compares the virtual DOM tree with the previous version to determine which node gets updated, ensuring that the updated node matches up with the actual DOM.

When React diffs two virtual DOM trees, it begins by comparing whether or not both snapshots have the same root element. If they have the same elements, like in our case, where the updated nodes are of the same span element type, React moves on and recurses on the attributes.

In both snapshots, no attribute is present or updated on the span element. React then repeats the procedure on the children. Upon seeing that the Time text node has changed, React will only update the actual node in the real DOM.

On the other hand, if both snapshots have different element types, which is rare in most updates, React will destroy the old DOM nodes and build a new one. For instance, going from span to div, as shown in the respective code snippets below:

<span>Time: 04:36:35</span> <div>Time: 04:36:38</div>

In the following example, we render a simple React component that updates the component state after a button click:

import { useState } from "react";

const App = () => {

const [open, setOpen] = useState(false);

return (

<div className="App">

<button onClick={() => setOpen((prev) => !prev)}>toggle</button>

<div className={open ? "open" : "close"}>

I'm {open ? "opened" : "closed"}

</div>

</div>

);

};

export default App;

Updating the component state re-renders the component. However, as shown below, on every re-render, React knows only to update the class name and the text that changed. This update will not hurt unaffected elements in the render:

See the code and demo on CodeSandbox.

When we modify a list of items, how React diffs the list depends on whether the items are added at the beginning or the end of the list. Consider the following list:

<ul> <li>item 3</li> <li>item 4</li> <li>item 5</li> </ul>

On the next update, let’s append an item 6 at the end, like so:

<ul> <li>item 3</li> <li>item 4</li> <li>item 5</li> <li>item 6</li> </ul>

React compares the items from the top. It matches the first, second, and third items, and knows only to insert the last item. This computation is straightforward for React.

However, let’s insert item 2 at the beginning, as follows:

<ul> <li>item 2</li> <li>item 3</li> <li>item 4</li> <li>item 5</li> </ul>

Similarly, React compares from the top, and immediately realizes that item 3 doesn’t match item 2 of the updated tree. It therefore sees the list as an entirely new one that needs to be rebuilt.

Instead of rebuilding the entire list, we want the DOM to compute minimal operations by only prepending item 2. React lets us add a key prop to uniquely identify the items as follows:

<ul> <li key="3">item 3</li> <li key="4">item 4</li> <li key="5">item 5</li> </ul> <ul> <li key="2">item 2</li> <li key="3">item 3</li> <li key="4">item 4</li> <li key="5">item 5</li> <li key="6">item 6</li> </ul>

With the implementation above, React would know that we have prepended item 2 and appended item 6. As a result, it would work to preserve the items that are already available and add only the new items in the DOM.

If we omit the key prop whenever we map to render a list of items, React is kind enough to alert us in the browser console.

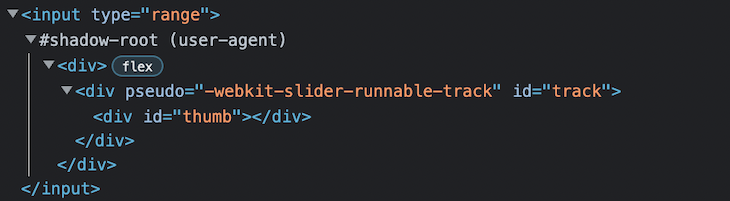

Before we wrap up, here’s a question that often comes up. Is the shadow DOM the same as the virtual DOM? The short answer is that their behavior is different.

The shadow DOM is a tool for implementing web components. Take, for instance, the HTML input element range:

<input type="range" />

This gives us the following result:

If we inspect the element using the browser’s developer tools, we’ll see only a simple input element. However, internally, browsers encapsulate and hide other elements and styles that make up the input slider.

Using Chrome DevTools, we can enable the Show user agent shadow DOM option from Settings to see the shadow DOM:

In the image above, the structured tree of elements from the #shadow-root inside the input element is called the shadow DOM tree. It provides a way to isolate components, including styles from the actual DOM.

Therefore, we’re sure that a widget or component’s style, like the input range above, is preserved no matter where it is rendered. In other words, their behavior or appearance is never affected by other elements’ styles from the real DOM.

The table below summarizes the differences between the real DOM, the virtual DOM, and the shadow DOM:

| Real DOM | Virtual DOM | Shadow DOM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | An interface for web documents; allows scripts to interact with the document | An in-memory replica of the actual DOM | A tool for implementing web components, or an isolated DOM tree within an actual DOM for scoping purposes |

| Relevance to developers | Developers manually perform DOM operations to manipulate the DOM | Developers don’t have to worry about state transitions; the virtual DOM abstracts DOM manipulation away from the developer | Developers can create reusable web components without worrying about style conflicts from the hosting document |

| Who uses them | Implemented in browsers | Used by libraries and frameworks like React, Vue, etc. | Used by web components |

| Project complexity | Suitable for simple, small to medium-scale projects without complex interactivity | Suitable for complex projects with a high level of interactivity | Suitable for simple to medium-scale projects with less complex interactivity |

| CPU and memory usage | When compared to virtual DOM updates, real DOM uses less CPU and memory | When compared to real DOM updates, virtual DOM uses more CPU and memory | When compared to virtual DOM updates, shadow DOM uses less CPU and memory |

| Encapsulation | Does not support encapsulation since components can be modified outside of its scope | Supports encapsulation as components cannot be modified outside of its scope | Supports encapsulation as components cannot be modified outside of its scope |

React uses the virtual DOM as a strategy to compute minimal DOM operations when re-rendering the UI. It is not in rivalry with or faster than the real DOM.

The virtual DOM provides a mechanism that abstracts manual DOM manipulations away from the developer, helping us to write more predictable code. It does so by comparing two render trees to determine exactly what has changed, only updating what is necessary on the actual DOM.

Like React, Vue also employs this strategy. However, Svelte proposes another approach to ensure that an application is optimized, compiling all components into independent, tiny JavaScript modules, making the script very light and fast to run.

I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Be sure to share your thoughts in the comment section if you have questions or contributions.

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Not sure if low-code is right for your next project? This guide breaks down when to use it, when to avoid it, and how to make the right call.

Compare Firebase Studio, Lovable, and Replit for AI-powered app building. Find the best tool for your project needs.

Discover how to use Gemini CLI, Google’s new open-source AI agent that brings Gemini directly to your terminal.

This article explores several proven patterns for writing safer, cleaner, and more readable code in React and TypeScript.

6 Replies to "What is the virtual DOM in React?"

I loved it!

Amazing!

Thank you for nice article, It helped me visualize how virtual dom works under the hood.

What an amazing article man. Incredible examples and representations.

Thank you for the great article it helped me understand the concept of real & virtual DOM through such amazing examples & illustrations.

A summary of my understanding is that the main DOM is a tree structure of all the elements in the HTML page. When there’s changes in the UI, re-rendering the whole page is costly so in react there’s the concept of virtual DOM where in memory objects are used to keep track of the changes in UI. React uses reconciliation (a diffing algo to compare the snapshots of the virtual DOM tree) & ReactDOM library to update the actual DOM.

Why use all this HTML in JS code? If we can render only the element where the clock will be. The Form is a separate component. The example does not contain anything useful