A healthy and productive relationship with your product manager will keep you sane, help you achieve results, and skyrocket your career; a toxic one will quickly lead to burnout and job dissatisfaction. That’s why collaboration with a product manager is a fundamental part of every UX designer’s job.

Establishing a proper relationship with a product manager is so critical that’s it worth conscious thought and effort, so let’s explore how to make the most out of this relationship.

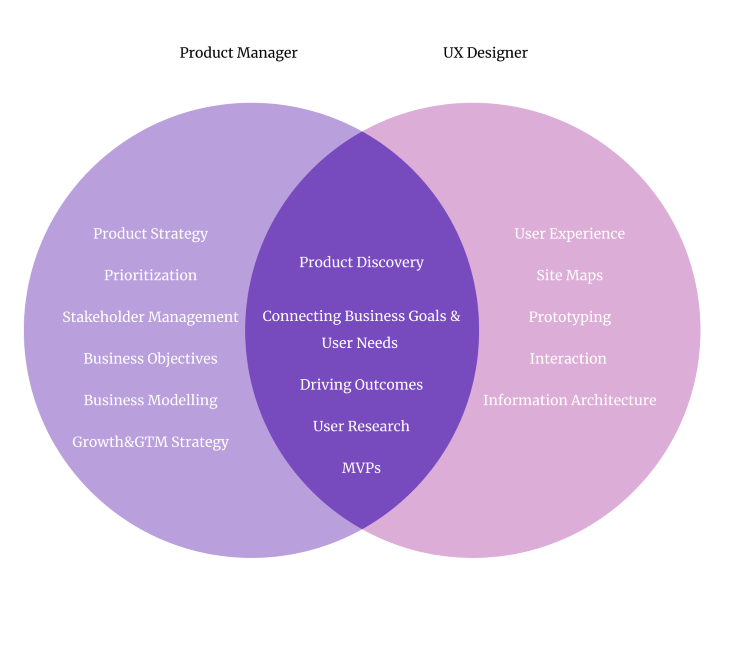

The biggest challenge of UX-PM collaboration is the overlap both roles have.

While there’s a big overlap of shared activities and goals, both roles approach it from different perspectives.

The difference in day-to-day activities of both UX designers and product managers causes them to adopt different mental models, ways of thinking, and perspective.

These differences, if left unmanaged, can easily lead to conflicts and disagreements.

But if both sides put in a conscious effort to benefit from these differences, they can lead to remarkable outcomes.

Let’s learn how.

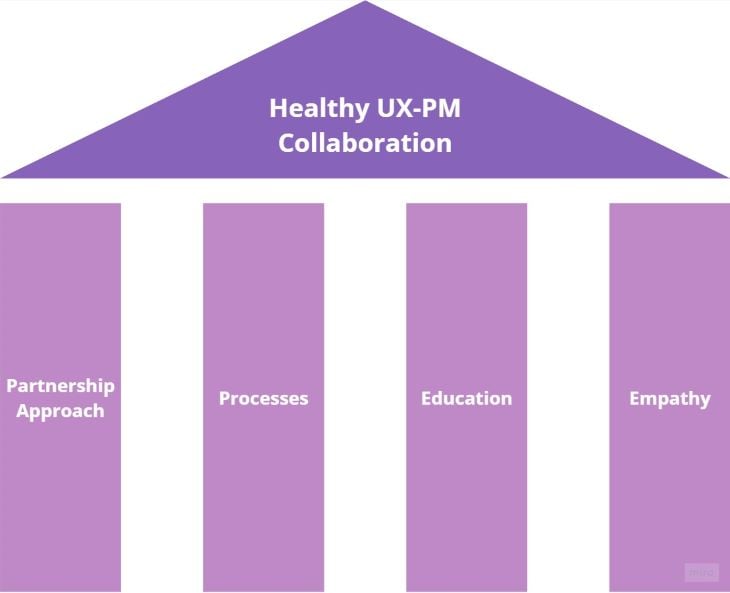

After investigating my relationships with my UX designers and interviewing other experienced PMs and UX designers, I came up with a pillars theory of UX-PM collaboration.

A healthy collaboration is built on:

Take care of these pillars, and you’ll boost your career, growth, and job satisfaction tremendously.

One of the most common issues with UX-PM collaboration is the transactional relationship. In way too many cases it looks like this:

You don’t want it to look like that.

A healthy relationship is based on a partnership where the PM and UX designer collaborate to solve meaningful problems and reach shared goals.

There are a few things you can do as a UX designer to cultivate such a partnership.

The first step is to change the way you think about the relationship.

You must perceive a product manager as your partner. You are both trying to do cool stuff and reach product and user objectives.

When a PM comes with a request, don’t frame it in your head as “PM tells me to do X” or “I was given a task Y.” Think about it as “my business partner believes that we should focus on X.”

Also, you are not trying to “manage up” by convincing the PM to go in a particular direction. You are negotiating with your partner about where to focus next.

It might seem small, but it goes a long way. The way you think encourages the way you act.

Without this mental shift, it will be hard to build a healthy partnership.

You and your partner must work on shared goals…

It might seem obvious, but that’s often not the case in reality.

UX designers often think about goals such as “let’s improve the usability of feature X,” while PMs often think about goals such as “let’s improve retention.”

But these are the same goals! You can drive retention by improving usability.

The framing makes an enormous difference. If you frame the shared goal as improving retention, and one of the ways to do so is by improving the usability of feature X, you open different conversations.

It becomes clearer to the PM how pursuing usability improvements can contribute to business objectives. It also opens your way of thinking of other UX-related enhancements that can help achieve the retention objective.

Talking about one goal from different perspectives invites more meaningful conversations than discussions whose goals are more important.

Focus on commonalities, not differences.

PM and UX designers should work together on all phases of the design process.

One of the things you can do is to invite product managers early in the process. Don’t work in a silo just to show a fully-fledged concept after a week.

Share your early insights with a product manager, and discuss your scrappy first wireframe as soon as possible.

Early feedback invites valuable conversations. It gives you both an opportunity to discuss differences, choose direction, and plan pivots early on.

Just be transparent when you are showing an early draft created to facilitate a discussion, and trust me, you won’t be judged by unpolished buttons and copy.

On the other hand, if you misunderstand each other early on and then only catch it during the handoff, you increase the risk of conflicts, last-minute workarounds, and mutual disappointment.

UX designers often want a seat at the proverbial table, and that’s good.

But if you are currently in a transactional relationship where the PM just brings you ideas to execute, waiting for the invitation probably isn’t the right strategy.

I won’t go into details about why UX designers are often not invited to the table — there might be various reasons depending on a particular contact. But the point is, you often have to fight for the seat yourself.

There are two tactics that can help you invite yourself to the table:

A simple question such as, “How can I help you, apart from doing the work assigned?” can go a long way.

Product managers sometimes simply forget that they have skilled specialists on board who can help them solve their challenges.

Maybe the PM is currently thinking about how to improve the trial conversion but, for some reason, forgot to include you in the conversation. Regularly offering to lend the PM a hand can help you uncover collaboration opportunities you didn’t see before.

Also, make sure to improve your pitches. Use business language and outcome orientation with every idea you have. For example, say you’ve learned that user onboarding is too long — most users drop out in the middle.

Instead of going with “let’s shorten the onboarding because users drop out anyway,” try to come up with a more specific, business-oriented hypothesis, such as “I believe that if we reduce two screens from onboarding, our trial conversion rate will increase because more people will reach the free trial offer screen at the end of onboarding.”

Always show how your ideas can drive business objectives. Do your homework.

Keep offering to lend a hand and produce high-quality, business-oriented pitches, and soon enough, a PM will acknowledge you as a great partner, not just a pixel pusher.

A collaboration doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

Instead, it’s built on top of the processes and routines you have with your partner. Improving the health of these processes is one of the best ways to improve the health of the UX-PM relationship.

There are hundreds of tools that can be used for specific goals.

Make sure you and your PM use the same ones.

The tools we use frame the way we think. If you map your opportunity space using Opportunity Solutions Trees, and your PM uses the RICE table, the way you assess opportunities and look at the big picture will differ greatly.

On the other hand, shared artifacts invite shared views and structured debates.

Using shared tools is significantly more important than using the “best” tools. You might believe that your Opportunity Solution Tree is a more effective tool than PM’s RICE table, but if the company requires all product teams to use the latter, just go with the company standards.

You might be tempted to use your own tools as “support material.” I don’t recommend that. It encourages further misunderstandings.

Once again: shared tools are better than the best tools. Of course, you can try to pitch your preferred tools to the team, but that’s material for another article.

Collaboration doesn’t happen in an ad hoc manner. It’s a set of routines and rituals you and your business partner share.

If you only talk with the PM during sprint planning and review, then something is off. For effective collaboration, you need multiple touchpoints.

If they are not in place, proactively push to set them up. Some of the most effective routines I know include:

Also, consider regular UX-PM retrospectives. Even if you have shared team retrospectives, UX-PM collaboration is so critical to product success that it deserves a separate deep dive.

Keep experimenting with different touchpoints and routines for the most efficient collaboration. At the end of the day, the health of your relationships depends heavily on the health of your process.

A great collaboration requires both sides to have a strong fundamental knowledge of the other’s work. It’s hard to understand where the other person comes from if you don’t know much about their job.

Sometimes, UX designers are disappointed that the PM lacks the UX knowledge they have.

Instead of expecting PMs to know that, teach your partner the basics.

PMs come in various shapes. If your PM doesn’t get your work, and you need them to get your work to be effective, set it as your goal to educate the PM on UX knowledge.

At the end of the day, this way you are helping yourself.

Sneak some knowledge and insights when sharing your designs and give them a little bit more explanation when justifying your decisions.

You can even offer periodical 1-1 sessions where you’ll explain some UX basics using your product’s examples. Just make sure to frame it the right way. You are not “teaching the PM UX basics.” You are “helping the PM drive better results by understanding the UX of the product.” Don’t make the PM feel patronized; people hate that.

Ideally, PMs should feel the need to learn UX on their own. But if they don’t, help yourself out by helping them out.

The knowledge part goes both ways. You also need a fundamental knowledge of how the business works.

Ideally, your PM will guide you and help you grasp the basics. Set clear expectations that you want to learn as much as possible to pitch better ideas and help drive business outcomes.

But also learn on your own.

Talk with various people in the company and understand the basics, such as:

One of the best investments you can make is to step up your data game. Learn how to analyze data, draw conclusions and assess the impact of your ideas. It’ll help you find a common language with your PM. Product managers love numbers.

Last but not least, empathy is critical.

The shared empathy is a byproduct of your processes, shared tools, and educating each other. It develops over time.

However, there are two things you should keep in mind when interpreting the PM’s actions and decisions.

This chapter will be a bit more theoretical but should help you see a product manager in a different light.

It’s infrequent that the PM makes 100 percent of their decisions based fully on their opinion.

There’s often a vast organizational context that influences that.

They might be pushing for that button color change, even though they are not UI experts, simply because the CEO decided to make it their pet project, and they don’t even have much to say.

Or they might already know that the sales department will hang them if they pursue your pitch rather than their request, but they find it politically incorrect to tell you so openly.

Don’t kill the messenger.

Trust me, PMs are rarely ignorant people. But they have to deal with organizational context and play politics so you don’t have to.

Although you might not be able to do much to change that, visualizing all the complexity a PM has to deal with might help you come to terms with some unpopular decisions product managers make.

Even if you work toward common goals, engage in productive conversations, and have healthy debates, sometimes you’ll disagree.

At points like that, the PM is usually the role to make the final call. And you shouldn’t be angry about that.

At the end of the day, it’s a product manager who has to deal with stakeholders, justify the call and take the hit for downfalls of the decisions.

The next time the PM decides to take a direction you disagree with, just be happy that they will be the ones that have to defend the decisions and bear the consequences.

Let this sink in: a relationship with your PM can make or break your career.

It’s often more important than your skillset, the effort you put in, or the novelty of your ideas.

Thus, one of your main objectives should be to ensure this relationship is fruitful and efficient.

Remember the four pillars of this relationship:

Identify the weakest pillar in your current setup and figure out ways to improve it. Over time, the PM should reciprocate, and you’ll both work to strengthen the relationship. The ROI will be tremendous.

Sadly, there also might be cases where the PM, for some reason, is not interested in building a fruitful relationship with you. And there may be cases where you both try, but it doesn’t seem to work out.

If you tried everything and can’t make the relationship work, it might be time to change the team. A career is too short to waste it working with a product manager with whom you simply don’t click.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions and understands user feedback for you, automating the most time-intensive parts of your job and giving you more time to focus on great design.

See how design choices, interactions, and issues affect your users — get a demo of LogRocket today.

Adaptive interfaces personalize experiences using behavioral signals and machine learning. But when personalization becomes autonomous, systems can reinforce patterns, limit discovery, and shape user behavior in ways designers didn’t intend.

Security requirements shouldn’t come at the cost of usability. This guide outlines 10 practical heuristics to design 2FA flows that protect users while minimizing friction, confusion, and recovery failures.

2FA failures shouldn’t mean permanent lockout. This guide breaks down recovery methods, failure handling, progressive disclosure, and UX strategies to balance security with accessibility.

Two-factor authentication should be secure, but it shouldn’t frustrate users. This guide explores standard 2FA user flow patterns for SMS, TOTP, and biometrics, along with edge cases, recovery strategies, and UX best practices.