Editor’s note: This article was updated by David Omotayo in December 2025 to reflect modern TypeScript usage, including deeper guidance on type aliases vs. interfaces, template literal and mapped types, performance considerations around polymorphism, and common misconceptions surfaced by readers.

We have two options for defining types in TypeScript: types and interfaces. One of the most frequently asked questions about TypeScript is whether we should use interfaces or types.

The answer to this question, like many programming questions, is that it depends. In some cases, one has a clear advantage over the other, but in many cases, they are interchangeable.

In this article, I will discuss the key differences and similarities between types and interfaces and explore when it is appropriate to use each one.

Let’s start with the basics of types and interfaces.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

type is a keyword in TypeScript that we can use to define the shape of data. The basic types in TypeScript include:

Each has unique features and purposes, allowing developers to choose the appropriate one for their particular use case.

Type aliases in TypeScript mean “a name for any type.” They provide a way of creating new names for existing types. Type aliases don’t define new types; instead, they provide an alternative name for an existing type.

Type aliases can be created using the type keyword, referring to any valid TypeScript type, including primitive types:

type MyNumber = number;

type User = {

id: number;

name: string;

email: string;

}

In the above example, we create two type aliases: MyNumber and User. We can use MyNumber as shorthand for a number type and use User type aliases to represent the type definition of a user.

When we say “types versus interfaces,” we refer to “type aliases versus interfaces.” For example, you can create the following aliases:

type ErrorCode = string | number; type Answer = string | number;

The two type aliases above represent alternative names for the same union type: string | number. While the underlying type is the same, the different names express different intents, which makes the code more readable.

In TypeScript, an interface defines a contract that an object must adhere to. Below is an example:

interface Client {

name: string;

address: string;

}

We can express the same Client contract definition using type annotations:

type Client = {

name: string;

address: string;

};

For the above case, we can use either type or interface. But there are some scenarios in which using type instead of interface makes a difference.

Primitive types are built-in types in TypeScript. They include number, string, boolean, null, and undefined types.

We can define a type alias for a primitive type like so:

type Address = string;

We often combine primitive type with union type to define a type alias, to make the code more readable:

type NullOrUndefined = null | undefined;

But we can’t use an interface to alias a primitive type. The interface can only be used for an object type.

Therefore, when we need to define a primitive type alias, we use type.

Union types allow us to describe values that can be one of several types and create unions of various primitive, literal, or complex types:

type Transport = 'Bus' | 'Car' | 'Bike' | 'Walk';

Union type can only be defined using type. There is no equivalent to a union type in an interface. But, it is possible to create a new union type from two interfaces, like so:

interface CarBattery {

power: number;

}

interface Engine {

type: string;

}

type HybridCar = Engine | CarBattery;

In TypeScript, a function type represents a function’s type signature. Using the type alias, we need to specify the parameters and the return type to define a function type:

type AddFn = (num1: number, num2:number) => number;

We can also use an interface to represent the function type:

interface IAdd {

(num1: number, num2:number): number;

}

Both type and interface similarly define function types, except for a subtle syntax difference of interface using : vs. => when using type. Type is preferred in this case because it’s shorter and thus easier to read.

Another reason to use type for defining a function type is its capabilities that the interface lacks. When the function becomes more complex, we can take advantage of the advanced type features such as conditional types, mapped types, etc. Here’s an example:

type Car = 'ICE' | 'EV';

type ChargeEV = (kws: number)=> void;

type FillPetrol = (type: string, liters: number) => void;

type RefillHandler<A extends Car> = A extends 'ICE' ? FillPetrol : A extends 'EV' ? ChargeEV : never;

const chargeTesla: RefillHandler<'EV'> = (power) => {

// Implementation for charging electric cars (EV)

};

const refillToyota: RefillHandler<'ICE'> = (fuelType, amount) => {

// Implementation for refilling internal combustion engine cars (ICE)

};

Here, we define a type RefillHander with conditional type and union type. It provides a unified function signature for EV and ICE handlers in a type-safe manner. We can’t achieve the same with the interface, as it doesn’t have the equivalent of conditional and union types.

Declaration merging is a feature that is exclusive to interfaces. With declaration merging, we can define an interface multiple times, and the TypeScript compiler will automatically merge these definitions into a single interface definition.

In the following example, the two Client interface definitions are merged into one by the TypeScript compiler, and we have two properties when using the Client interface:

interface Client {

name: string;

}

interface Client {

age: number;

}

const harry: Client = {

name: 'Harry',

age: 41

}

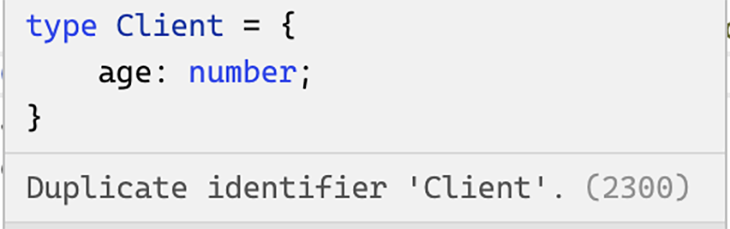

Type aliases can’t be merged in the same way. If you try to define the Client type more than once, as in the above example, an error will be thrown:

When used in the right places, declaration merging can be very useful. One common use case for declaration merging is to extend a third-party library’s type definition to fit the needs of a particular project.

If you need to merge declarations, interfaces are the way to go.

In TypeScript, both interfaces and type aliases can be extended to build on existing definitions. The key difference lies in how they express extension, interfaces use the extends keyword, while types use the intersection operator &.

An interface can extend one or multiple other interfaces. Using the extends keyword, a new interface can inherit all the properties and methods of an existing interface while adding its own unique members.

For example, we can create a VIPClient interface by extending a base Client interface:

interface Client {

name: string;

email: string;

}

interface VIPClient extends Client {

vipLevel: number;

}

Here, VIPClient inherits all members from Client and adds its own property, vipLevel.

To achieve a similar result using type aliases, you would use the intersection & operator:

type Client = {

name: string;

email: string;

};

type VIPClient = Client & {

vipLevel: number;

};

This creates a new type that combines all members from Client and the additional properties defined in the intersection.

You can also extend type aliases, as long as the alias represents a statically known object type:

type Client = {

name: string;

};

interface VIPClient extends Client {

benefits: string[]

}

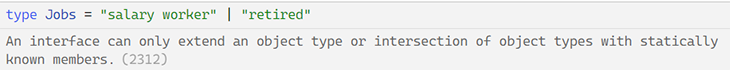

However, if the type alias is a union type, the compiler will throw an error:

type Jobs = 'salary worker' | 'retired';

interface MoreJobs extends Jobs {

description: string;

}

This happens because interfaces must have a statically known shape at compile time; unions don’t provide that.

That said, type aliases can also extend interfaces using intersections:

interface Client {

name: string;

}

Type VIPClient = Client & { benefits: string[]};

In a nutshell, both interfaces and type aliases can be extended, but they differ philosophically. Interfaces support polymorphism and inheritance patterns that closely resemble object-oriented programming concepts, while type aliases focus on composition and structural flexibility.

Let’s take a look at the following example:

interface Animal {

makeSound(): void;

}

interface Mammal extends Animal {

hasFur: boolean;

}

class Dog implements Mammal {

hasFur = true;

makeSound() {

console.log("Woof!");

}

}

class Cat implements Mammal {

hasFur = true;

makeSound() {

console.log("Meow!");

}

}

function animalSound(animal: Animal) {

animal.makeSound();

}

const dog = new Dog();

const cat = new Cat();

animalSound(dog); // Woof!

animalSound(cat); // Meow!

Here, the Animal interface defines a contract, which Mammal extends by adding a property. The Dog and Cat classes implement Mammal, exhibiting concrete behavior. Because interfaces support polymorphism, we can treat both Dog and Cat instances as Animal.

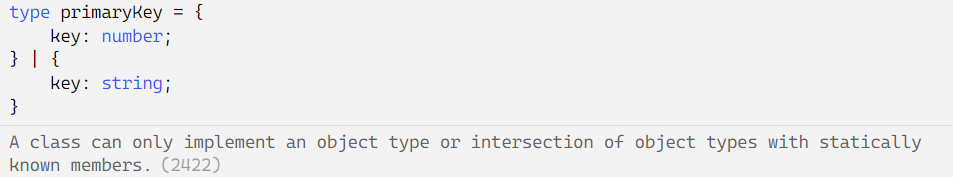

Type aliases can also implement classes, but only when the alias represents an object type (not a union):

type primaryKey = { key: number; } | { key: string; };

// can not implement a union type

class RealKey implements primaryKey {

key = 1

}

>

In the above example, the TypeScript compiler throws an error because a class represents a specific data shape, but a union type can be one of several data types.

Since type aliases cannot represent open or mergeable contracts, they don’t support polymorphism or class implementation in the same way interfaces do. The right choice depends on whether your design feels more object-oriented or functional.

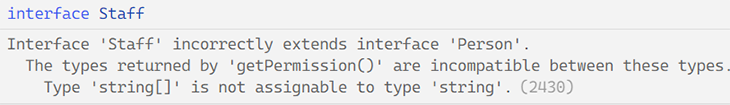

Another difference between types and interfaces is how conflicts are handled when you try to extend from one with the same property name.

When extending interfaces, the same property key isn’t allowed, as in the example below:

interface Person {

getPermission: () => string;

}

interface Staff extends Person {

getPermission: () => string[];

}

An error is thrown because a conflict is detected:

Type aliases handle conflicts differently. In the case of a type alias extending another type with the same property key, it will automatically merge all properties instead of throwing errors.

In the following example, the intersection operator merges the method signature of the two getPermission declarations, and a [typeof](https://blog.logrocket.com/how-to-use-keyof-operator-typescript/) operator is used to narrow down the union type parameter so that we can get the return value in a type-safe way:

type Person = {

getPermission: (id: string) => string;

};

type Staff = Person & {

getPermission: (id: string[]) => string[];

};

const AdminStaff: Staff = {

getPermission: (id: string | string[]) =>{

return (typeof id === 'string'? 'admin' : ['admin']) as string[] & string;

}

}

It is important to note that the type intersection of two properties may produce unexpected results. In the example below, the name property for the extended type Staff becomes never, since it can’t be both string and number at the same time:

type Person = {

name: string

};

type Staff = person & {

name: number

};

// error: Type 'string' is not assignable to type 'never'.(2322)

const Harry: Staff = { name: 'Harry' };

In summary, interfaces will detect property or method name conflicts at compile time and generate an error, whereas type intersections will merge the properties or methods without throwing errors. Therefore, if we need to overload functions, type aliases should be used.

Often, when using an interface, Typescript will generally do a better job displaying the shape of the interface in error messages, tooltips, and IDEs. It is also much easier to read, no matter how many types you combine or extend.

In contrast, when you use type aliases with intersections, such as type A = B & C;, and then reuse that alias in another intersection like type X = A & D;, TypeScript can struggle to display the full structure of the combined type. This can make it harder to interpret the resulting type’s shape from error messages or IntelliSense hints.

TypeScript caches the results of the evaluated relationship between interfaces, like whether one interface extends another or if two interfaces are compatible. This approach improves the overall performance when the same relationship is referenced in the future.

Whereas when working with intersections, TypeScript does not cache these relationships. Each time an intersection is used, TypeScript has to re-evaluate the entire type structure, which can lead to efficiency concerns. For these reasons, it is advisable to use interface extends instead of relying on type intersections.

In TypeScript, the tuple type allows us to express an array with a fixed number of elements, where each element has its own data type. It can be useful when you need to work with arrays of data with a fixed structure:

type TeamMember = [name: string, role: string, age: number

Since tuples have a fixed length and each position has a type assigned to it, TypeScript will raise an error if you try to add, remove, or modify elements in a way that violates this structure.

For example:

const member: TeamMember = ['Alice', ‘Dev’, 28]; member[3]; // Error: Tuple type '[string, string, number]' of length '3' has no element at index '3'.

Interfaces don’t have native support for tuple types. While you can mimic a tuple-like structure using workarounds like the example below, it’s not as concise or intuitive as defining a tuple directly:

interface ITeamMember extends Array<string | number>

{

0: string; 1: string; 2: number

}

const peter: ITeamMember = ['Harry', 'Dev', 24];

const Tom: ITeamMember = ['Tom', 30, 'Manager']; //Error: Type 'number' is not assignable to type 'string'.

Unlike tuples, this interface extends the generic Array type, which enables it to have any number of elements beyond the first three. This is because arrays in TypeScript are dynamic, and you can access or assign values to indices beyond the ones explicitly defined in the interface:

const peter: ITeamMember = [’Peter’, 'Dev', 24]; console.log(peter[3]); // No error, even though this element is undefined.

Aside from that, tuples offer better type inference; IDEs can infer element types by their index. That means when you hover or autocomplete member[0], it knows it’s a string. But with interface, TypeScript treats all indexes as the same general type (i.e. number | string | boolean), so you lose that per-index precision.

TypeScript provides a wide range of advanced type features that can’t be found in interfaces.

The template literal type is an eample of a feature that I find particularly interesting — and has become increasingly popular amongst developers these days.

This is a feature that allows you to create string literal types based on a template string’s content. It allows you to create more dynamic and expressive types based on the values you’re expecting in a template string. For example:

type Size = 'small' | 'medium' | 'large';

type SizeMessage = `The selected size is ${Size}.`;

let message: SizeMessage;

message = "The selected size is small."; // No error

message = "The selected size is huge."; // Error: not assignable

Here, we define a template literal type (SizeMessage) that concatenates the literal string “The selected size is” with each possible value from the Size union. In other words, SizeMessage automatically expands into this set of valid strings:

"The selected size is small." | "The selected size is medium." | "The selected size is large."

So when we declare let message: SizeMessage;, TypeScript knows that message must exactly match one of these three options.

That’s why assigning “The selected size is small” works perfectly because it matches one of the generated strings. But when we try “The selected size is huge.”, we get an error. The value doesn’t fit any of the allowed patterns, so it’s rejected at compile time.

Another advanced type feature worth mentioning is custom utility types. These are developer-defined utility types created using TypeScript’s features, such as mapped types, conditional types, and type inference, to transform or manipulate existing types.

This feature lets developers tailor type transformations beyond the built-in utilities (like Partial, Omit, and Required) to match their project needs.

For example, suppose you want to remove every null and undefined field from a type’s properties. Since TypeScript doesn’t include a built-in utility for this, you can define a custom one like this:

type NonNullableProps<T> = {

[K in keyof T]: NonNullable<T[K]>;

};

This custom utility type uses a mapped type to iterate over each property key K in the type T, and uses the built-in NonNullable utility to remove both null and undefined from the property’s type.

So, if you have the following example:

interface User {

id: number | null;

name: string | null;

age?: number;

}

type SafeUser = NonNullableProps<User>;

The SafeUser type becomes:

{

id: number;

name: string;

age: number;

}

SafeUser is a version of User where all properties are guaranteed to hold non-null, non-undefined values.

Beyond these, TypeScript also offers several other unique features, such as:

TypeScript’s typing system constantly evolves with every new release, making it a complex and powerful toolbox. The impressive typing system is one of the main reasons many developers prefer to use TypeScript.

Type aliases and interfaces are similar but have subtle differences, as shown in the previous section.

While almost all interface features are available in types or have equivalents, one exception is declaration merging. Interfaces should generally be used when declaration merging is necessary, such as extending an existing library or authoring a new one. Additionally, if you prefer the object-oriented inheritance style, using the extends keyword with an interface is often more readable than using the intersection with type aliases.

Interfaces with extends enables the compiler to be more performant, compared to type aliases with intersections.

However, many of the features in types are difficult or impossible to achieve with interfaces. For example, TypeScript provides rich features like conditional types, generic types, type guards, advanced types, and more. You can use them to build a well-constrained type system to make your app strongly typed. You can’t do this with interfaces.

In many cases, they can be used interchangeably depending on personal preference. But, we should use type aliases in the following use cases:

Compared with interfaces, types are more expressive. Many advanced type features are unavailable in interfaces, and those features continue to grow as TypeScript evolves.

Below is an example of the advanced type feature that the interface can’t achieve.

type Client = {

name: string;

address: string;

}

type Getters<T> = {

[K in keyof T as `get${Capitalize<string & K>}`]: () => T[K];

};

type clientType = Getters<Client>;

// type clientType = {

// getName: () => string;

// getAddress: () => string;

// }

Using mapped type, template literal types, and keyof operator, we created a type that automatically generates getter methods for any object type.

In addition, many developers prefer to use types because they match the functional programming paradigm well. The rich type expression makes it easier to achieve functional composition, immutability, and other functional programming capabilities in a type-safe manner.

Yes, in most cases. This is because they overlap in many ways, though there are notable differences as highlighted in the article, such as support for union types, mapped types, conditional types, and declaration merging.

The rule of thumb is:

Both are valid. If you plan on extending or merging props, interface might be preferable. If you need union types or complex mapped types, then go for a type alias.

Yes, but only if the type alias is a non-union object shape (e.g., type Person = { name: string }). You cannot use implements on a union alias.

In this article, we discussed type aliases and interfaces and their differences. While there are some scenarios in which one is preferred over the other, in most cases, the choice between them boils down to personal preference.

I lean towards using types simply because of the amazing type system. What are your preferences? You are welcome to share your opinions in the comments section below.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks, and with plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you understand your web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 11th issue.

Buying AI tools isn’t enough. Engineering teams need AI literacy programs to unlock real productivity gains and avoid uneven adoption.

If your AI app or agent works perfectly in development but falls apart in production, you’re not alone. In a […]

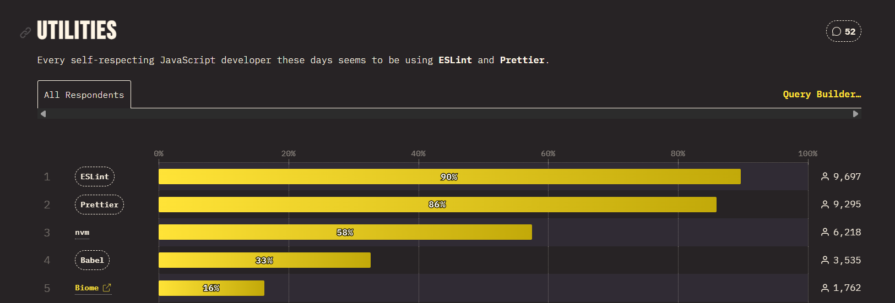

Compare ESLint and Oxlint, benchmark real speed gains, and learn when migrating to Oxlint makes sense for modern JavaScript teams.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

12 Replies to "Types vs. interfaces in TypeScript"

This article still leaves me confused. I still feel like I can use whichever.

Same here, not to having to concrete pro and cons. Still feel confused

To me type aliases are more strict, so it makes more sense for me to use that by default – even for objects. The only time I use interfaces is to expose types publicly so that the consumer of your code can extend the types if needed, or when implementing with a class.

In your example of that interface with tupe [string, number] is actually an interface that has one of its members defined as a type (of a tuple) so no confusion here.

One difference that you didn’t mention is when object implementing some interface can have more properties than the interface defines, but types limit the shape to exactly what type has defined.

“Interfaces are better when you need to define a new object or method of an object. For example, in React applications, when you need to define the props that a specific component is going to receive, it’s ideal to use interface over types”

There is no argumentation here. “object or method of an object”, while being vague, has nothing to do with a functional React component which is a function.

You’re just making more confusion.

There are so many errors in this!

1. “In TypeScript, we can easily extend and implement interfaces. This is not possible with types though.”

What? Classes can implement types. Types can “extend” types using ‘&’.

2. “We cannot create an interface combining two types, because it doesn’t work:”

Again, what? If A and B are interfaces, you can create an interface C like this:

interface C extends A, B {

}

This is a very misleading post.

I, personally, tend towards `type` when defining Prop types.

The things you get with `interface` (namely `implements`, and the ability to extend through redeclaration) aren’t really useful in the context of Prop definitions, but the things you get with `type` are (namely unions, intersections, and aliases specifically).

They’re mostly the same in this context, but occasionally you’ll end-up NEEDING to use type so you define PropsWithChildren using the react library type React.PropsWithChildren and since I prefer consistency, I’ll just use type for all PropTypes.

You say, “Interfaces are better when you need to define a new object or method of an object.”, and then straight away in the next box you use a type to define an object.

“`

type Person = {

name: string,

age: number

};

“`

So which one is it? The article doesn’t seem to adhere to its own advice which is confusing.

Great Thanks

Thank you!

Great article explaining complex things in a simple way.

Great stuff man, thanks a lot

Differences between types aliases and interfaces are not easy to understand, and sometimes we don’t know which one to use, that helped me to figure it out better

Years later and this is still easily one of my most referenced articles about Typescript. Thank you for the update!