In most cases, people try out a product, activate it, use it for a few weeks or months, and then churn. But there are also products that customers love and use for years. Spotify is a prime example.

What differentiates products that stick from those that don’t? Habits.

Products that can successfully help people build habits have lower churn rates and higher lifetime value (LTV). Put simply, habits make people come back regularly.

But how do you build products that build strong, long-lasting habits? One approach is to use the hook model, a habit-forming system described by Nir Eyal in his book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products.

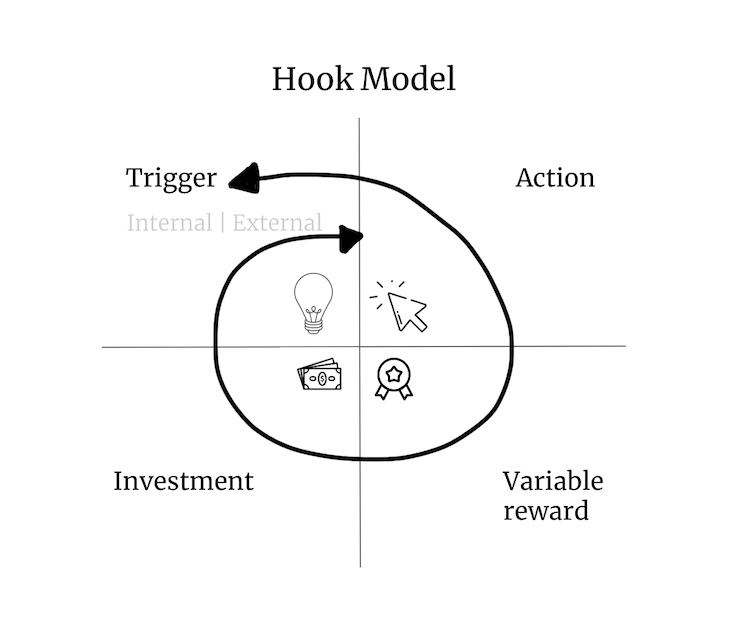

The hook model describes a user journey that is conducive to forming a strong habit. It starts with a trigger that prompts the user to take a specific action. A variable reward then follows the action, ending with user investment.

The more times the cycle repeats, the higher the chance the user will develop a habit.

The components of the hook model are as follows:

There are two types of triggers: internal and external.

An external trigger is a prompt that comes from the environment. Examples might include:

The more external triggers users experience, the higher the likelihood they will develop an internal trigger — a cue that comes from within. This usually includes feelings and thoughts.

To make it more tangible, let’s take a look at an example.

Say you’re scrolling through your Facebook feed. You’re probably at least mildly bored. Suddenly, you see an advertisement (trigger) from YouTube. You try it (action), watch a video (variable reward), and fine-tune the algorithm (investment) so that you get better recommendations.

The next day, a friend shares another YouTube video with you, so you bookmark it to watch it in the evening. Over time, you begin to associate watching cat videos with boredom — i.e., you develop an internal trigger.

Once that happens, you no longer need external triggers to take action. Your inner feeling of boredom will be enough to keep pushing you through the loop.

The most potent internal triggers are negative emotions, such as anxiety, fear of social disconnection, uncertainty, and, like in the example described above, boredom.

Action is the behavior a user goes through in anticipation of the reward. It is also the primary way of satisfying the trigger.

Back to the YouTube example: when you see an advertisement that sparks your curiosity, clicking the link to see whether the video is actually funny (variable reward) satisfies the trigger (curiosity). The same goes for when a friend shares a video with you.

If you have already developed an internal trigger, then going to the YouTube homepage (action) will help you find an interesting video (variable reward) and kill the boredom (satisfy the internal trigger).

To build habits, the action should be easier than even thinking about it. Triggers should almost automatically provoke an action. The more friction there is for completing the action, the less frequently a user will finish it, which is not conducive to developing a habit.

Factors that contribute to friction include:

Every bit of friction decreases the product’s chance of building a solid habit.

Every habit needs a reward — ideally, an unpredictable one.

That’s because predictable rewards don’t cause cravings. If the results are predictable, people quickly get bored with them.

Variable rewards, on the other hand, prompt an intense dopamine hit. In fact, craving for variability causes a stronger emotional reaction than the reward itself.

There are three types of variable rewards:

Variable rewards should satisfy the user’s needs while encouraging them to reengage with the product.

The variability should be infinite. Even if the reward is variable, if it offers a finite number of options, users will get used to it over time and the reward will become somewhat predictable.

An example of endless variability is user-generated content — there’s always something new and it’s hard to predict.

Although the trigger > action > reward cycle is enough to build habitual behaviors, one additional ingredient makes the habit-building process even more effective: user investment.

Actions users take should not only lead to instant variable rewards but should also be a small investment in improving future rewards’ quality. Some examples include:

The investment not only improves the variable reward but also makes leaving the product harder. If you have 20,000 reviews on eBay, you probably wouldn’t switch easily to Amazon, even though they might offer a better UX.

Also, after years of fine-tuning Spotify’s algorithm and building perfect playlists, changing the streaming service and starting from scratch feels like a good premise for a horror movie.

Just make sure the investments come in naturally. You don’t want to introduce too much friction just to increase the investment. Remember, the action part itself should be as simple as possible.

You might wonder, is it even ethical to use a hook model? Especially for something like a slot machine — isn’t it manipulative?

That’s a tricky question.

The hook model does take advantage of our brain’s flaws and natural mechanisms. But whether it’s wrong to employ the hook model depends on how you use it.

If you try to build user habits that are harmful just to earn some money, then without a doubt, you are using the hook model unethically.

But you can use the model to help people. Think about Duolingo: the whole product is designed to help users build strong learning habits. These habits then help users learn new languages more effortlessly and, as a result, grow as people. I firmly believe using the hook model in this way is more than ethical.

At the end of the day, the hook model is just a tool.

Among the best-performing products are those that build new habits for their users. If people come back habitually, the likelihood they will churn decreases dramatically.

Let’s recap: to build a habit, you need three ingredients:

Although true habits are based on internal triggers, such as emotions, products must first rely on external triggers to put people in the loop enough times to start building associations with internal triggers.

Truly long-lasting habits require an additional ingredient: an investment. Something that improves the quality of the reward over time. The more significant the investment, the harder it’s a give up a product.

The hook model itself is just a tool. Whether hooking users is ethical or not depends on how you use it. Make sure the habits your product strives to build enhance users’ lives, not harm them.

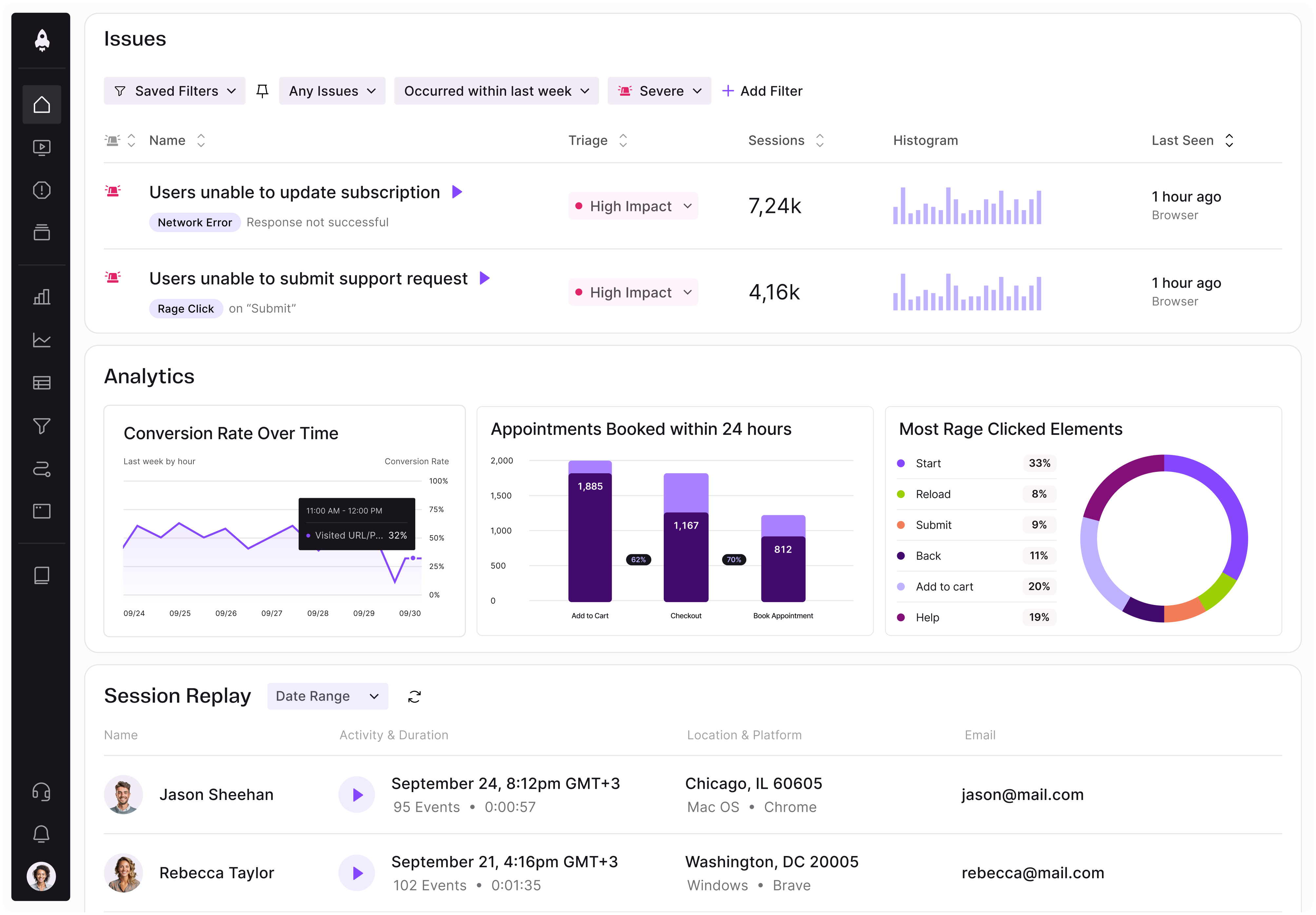

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

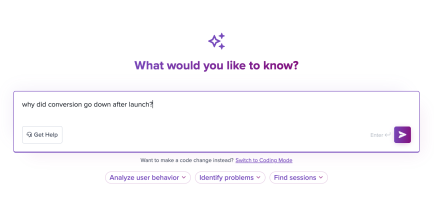

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.