Are you a betting person? Investing your resources in yet another methodology can feel daunting. However, if you’re used to arduous sprints and scrum processes, Shape Up is a breath of fresh air.

The Shape Up methodology wasn’t conceived at a sunny California seminar or by an enlightened guru; it was designed by and for project and product teams at Basecamp/37signals, the seminal software company.

Shape Up’s practical nature from the get-go makes it applicable to many industries outside of software development. The Shape Up method intends to improve project/product and time awareness, avoiding the disconnect between teams and tasks.

In this guide, we’ll cover everything product managers need to know about Shape Up, including its history, why and when to use it, and key concepts. Then, we’ll unlock the secrets to its successful implementation.

The Shape Up methodology is an approach to product development and optimization that prioritizes shipping.

In theory, all productivity approaches are focused on launching a finalized product or service. But that’s not how it always works in practice.

Take time-blocking techniques, for example. Often, instead of limiting the amount of time spent on a given task, this approach can lead to teams spending exactly the predetermined amount of time, regardless of the size or complexity of the task. In other words, a time efficiency tool can become a time-sucking trap if not managed correctly.

Teams can also become obsessed with key metrics that are nevertheless disconnected from the final product and customer expectations. The hustle involved in executing agile methodologies can cause teams to forget about what really matters, overlooking important work to prioritize busywork. This is where Shape Up comes in.

The basic principles of the Shape Up methodology are as follows (as described by its creators at Basecamp):

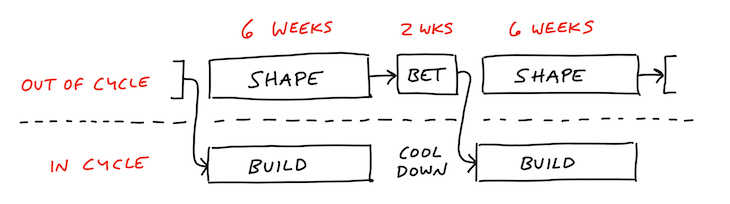

The best-known component of the Shape Up approach is the six-week cycle. This is a predetermined timeline that cannot be postponed.

The timeline is not necessarily broken up into time blocks. Rather, everyone engaged in the product knows that new features, technical solutions or design improvements must be ready in six weeks.

This does not mean, however, that chaos reigns.

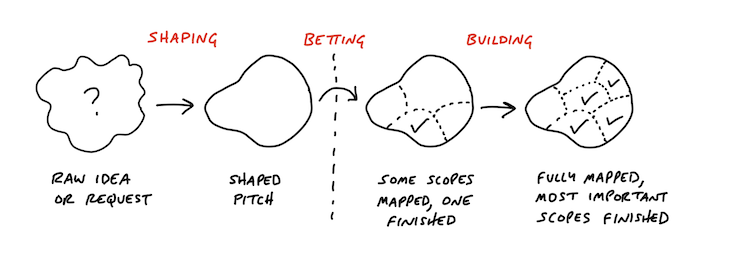

The second component, work-shaping, involves senior team members figuring out the component or solution’s vital steps.

This is not an exact science, but is based on a manager’s deep knowledge of the team’s capabilities and current capacity. What can actually be executed in six weeks that will drive the project forward?

Teams pick up this mandate from senior managers and truly endeavor to make it their own. In other words, teams are fully accountable and responsible for outlining milestones, fitting goals to capacities, and understanding key dependencies and bottlenecks.

Rather than micromanaging, senior team members specialize in shaping projects while delegating execution to teams.

Finally, Shape Up specifically targets one risk common to all product teams: missing the deadline.

Rather than spending months pursuing blue sky thinking and tying down your teams with fully scheduled weeks, shaping identifies gaps, needs and questions before execution. Those six weeks cannot be extended, so solutions are tested early, stakeholders talk from the get-go, and useless backlogs are not carried over to new projects.

While the attachment to these four key principles might seem radical, the following section will make you understand why the folks at Basecamp/37signals came up with this solution.

According to Jason Fried, Basecamp/37signals’ software and the resulting Shape Up methodology resulted from a decade and a half of iterating different approaches to work and productivity. As its product portfolio grew, the company saw value in bundling its SaaS solutions.

After it successfully launched the bundle, Basecamp grew even more, and new entrants, as talented as they were, obviously lacked the attachment to original product philosophies. That is the nature of rapid personnel development: what you gain in capacity, you lose in adaptability and agility of communication.

It is easy to understand why instinctive, rapidly agreed-upon product decisions are basically impossible to execute once any firm grows to a significant size. Time is scarce, schedules become misaligned, and directionality is lost in translation. What did they do at Basecamp to prevent falling into this growth trap?

Above all, instead of implementing ongoing deadlines or ad-hoc project pipelines, they settled on cycles as a time management approach. After testing, six weeks seemed like the appropriate length: a long enough cycle to allow for significant impact on the project, but short enough so the deadline forces teams to make decisions quickly.

The remaining principles developed naturally. The company had grown to the point where leaders no longer had the time to direct teams. However, replacing leadership with strict rules and hierarchies seemed like a great way to constrain creative solutions.

As a solution, leaders at Basecamp focus on high-level planning — i.e., shaping. Teams are not constantly monitored; they just need to worry about one thing: shipping.

This division of labor that would become the Shape Up methodology enabled Basecamp to keep growing without compromising the agility and innovation that drove success during its early years.

Product managers looking to implement the Shape Up methodology in their organization should take the following steps and answer the questions as outline below.

The final step is to ship your product and start the process again from the beginning.

Product organizations often encounter roadblocks around team morale, manager bandwidth, and the human tendency to go through the motions. Shape Up is designed to help all involved in product development focus on what really matters: shipping products.

To help teams meet these challenges head-on, the Shape Up methodology enables product managers to:

Let’s say, for example, that your teams have become stuck or demoralized by constant scrums, with moving deadlines, growing backlogs, and constant changes in direction. The Shape Up methodology provides relief because after six weeks, you are allowed to start again.

Product teams are likely to take this as a breath of fresh air, particularly once they find out that shipping will allow them to define tasks and milestones — as long as they fulfill the brief, of course.

Managers spend too much time bogged down by small issues and have lost sight of the bigger picture. Senior members of the team are constantly having to supervise project stakeholders, relay communications, ensure that deadlines are met, and instill accountability across the board.

Shape Up switches this up, delegating responsibility to teams and liberating time for managers to focus on matching capacities with goals.

The customer is no longer in the picture; their voice has been replaced by meaningless metrics and novelty sprint techniques.

If an approach has been in place for a long time, it’s common for teams and managers to spend too much time ticking boxes. Shape Up forces both parties to disregard useless goals and focus on what really matters: releasing features and products.

At the same time, it is important to avoid becoming too attached to tasks and backlogs. Shape Up is meant to force you to do the opposite: after six weeks, it’s a new day!

Another potential drawback is managers not taking the shaping phase seriously. Without an outline that is realistic about milestones, capabilities, traps, dependencies and strategy, your teams will still run around like a flock of headless chickens.

If you keep these issues in mind, you’ll avoid a lot of problems once you start shaping up your products.

Shape Up can be particularly useful for:

This is exactly why Basecamp developed Shape Up. Fast-growing spaces are excellent sites to shape up, so to speak, because teams and leaders can quickly lose sight of what’s important while dealing with the tiny emerging crises that come from quick development.

With the clear six-week directive, product teams can easily accommodate growth while retaining key principles across each cycle.

It is no coincidence that Shape Up emerged during the digital product revolution. Rather than adjusting goods and services to the whims of powerful project managers, product teams emphasize product development to serve customer needs (whether internal or external).

The emphasis on shaping requirements and launching quickly makes Shape Up a perfect system for most digital teams.

Certain types of products and services become obsolete really quickly. Think of smartphones and smart TVs, whose hardware, power, and functionalities expand dramatically with each iteration.

Shape Up’s changing cycles are perfectly suited for scenarios where evolving requirements and expanding possibilities impact product strategy.

Basically, when your sector of choice has no external limits or constraints, particularly in terms of time, Shape Up is a great technique to organize work. You just have to look at the advantages listed here and decide whether it’s the best for you and your team.

Conversely, the Shape Up methodology is less suitable for the following types of organization:

Large firms and established teams might find it difficult to implement Shape Up. Change is risky, and if something isn’t broken, why try to fix it?

Moreover, traditional corporate giants often have certain ways of working for a reason. It is dangerous to challenge a company’s business culture without the backing of very senior leadership or the resources to hire external consultants.

Some teams focus less on launching solutions and more on running things continuously. Think of a customer service division at an airline, for example: if the team were to cycle through chat systems and complaint pathways every six weeks, customers would quickly lose patience and resort to sending emails rather than dealing with the website or app.

In scenarios like this, it might be more appropriate to eschew a methodology like Shape Up.

Some technologies and innovations that take decades to materialize. For example, pharmaceutical sector products have extremely long cycles from their initial conception in university basic research to their final deployment across hospitals and pharmacies.

Shape Up might be useful at certain discrete stages, but it is not recommended as a foundation for product and service design for long-cycle technologies.

With sector-specific companies, the point is to highlight how product development can be affected by business factors connected to a specific area of the economy.

The defense sector, for example, is almost exclusively dedicated to service government clients that might have their own understanding and priorities. There might be explicit safety regulations and clear reasons as to why project milestones cannot be limited to six weeks, for instance, or senior leaders cannot delegate responsibility to lower-level teams.

The Shape Up methodology, developed at Basecamp and widely adopted in the software development world and beyond, is a great way to help product teams focus on what’s most important: shipping products.

The pillars of the Shape Up methodology are as follows:

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

The continuous improvement process (CIP) provides a structured approach to delivering incremental product enhancements.

As a PM, you’re responsible for functional requirements and it’s vital that you don’t confuse them with other requirements.

Melani Cummings, VP of Product and UX at Fabletics, talks about the nuances of omnichannel strategy in a membership-based company.

Monitoring customer experience KPIs helps companies understand customer satisfaction, loyalty, and the overall experience.