PDCA (plan-do-check-act or plan-do-check-adjust) is one of the most important management concepts from the past century. With original concepts from the 1930s and established in 1950, it is a cornerstone of the Toyota Production System, modern product management, and agile product development.

Plan-do-check-act revolves around continuous improvement. This is why it is depicted as a cycle. In this article, we’ll learn about the history of PDCA, the four stages of the PDCA cycle, how it impacted manufacturing, and how it’s now changing product management.

PDCA has its roots in the scientific method, which is 400 years old. Formed by Galileo Galilei and completed by Francis Bacon, the scientific method was foundational for scientific breakthroughs since the Enlightenment.

The premise of the scientific method is empiricism, which stresses the importance of observation and evidence over assumptions. You may have an assumption, but you can only draw conclusions through experimentation and observing the results. This then allows you to create new assumptions to verify.

The next important moment in the creation of PDCA came in the 1930s. Though the PDCA cycle is widely known as the Deming Wheel (named after W. Edwards Deming), Deming himself preferred calling it the Shewart cycle because Walter Shewart had the original idea.

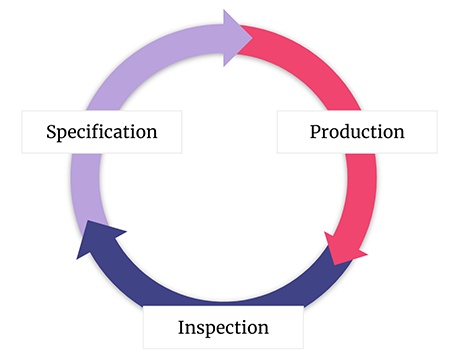

Walter A. Shewart’s concept from 1939 was a cycle with the following steps: specification, production, and inspection:

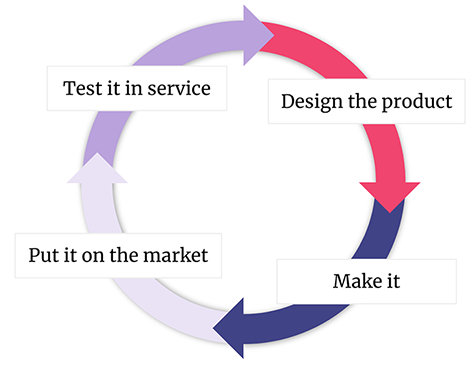

But what does this cycle really mean? What do specification, production, and inspection imply? Here it is in simpler terms, with an added step to have it come together more cohesively:

The final push to create the PDCA cycle happened in 1950. Deming was in Japan where he trained engineers, managers, and executives to provide them with insights to rebuild the Japanese economy after World War II. During one of the training sessions, the Japanese participants translated Deming’s cycle to “plan-do-check-act.”

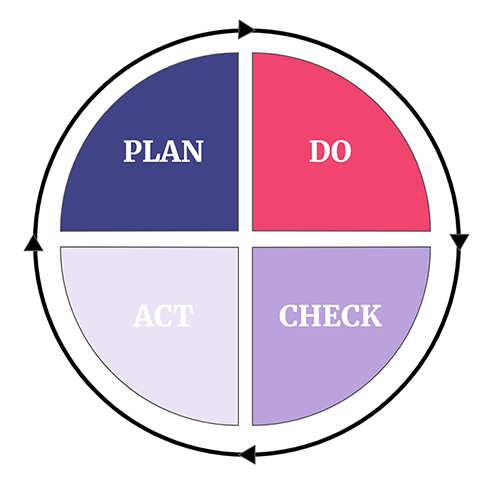

PDCA’s learning cycle serves the same purpose as empiricism: to verify assumptions by learning from your experiments. The four stages are plan, do, check, act:

The learning cycle starts with an assumption on how you can best achieve your goal and creates a plan to take a small step towards this goal. This includes defining the goal, targets, and measures to understand how to progress toward the goal.

Next, you do the work according to plan.

Then, you check what you can learn from the work.

Finally, you act to optimize your chances of achieving your goal.

Then the cycle is repeated, planning the next step in a new iteration.

PDCA underlines the importance of seeking evidence to optimize the chances of achieving your goal. The premise of the PDCA loop is to gather new information and learn by doing. It can only function when the organization is embracing chance. Without the willingness to change how you do the work, PDCA will fail.

PDCA is most commonly known as plan-do-check-act. However, it is also referred to as plan-do-check-adjust to reflect the adjustment of processes based on the learnings.

In 1993, Deming — who was 93 at the time — reworded it to PDSA, which means plan-do-study-act. He argued that “check” has negative connotations, as in “checking if people did the work according to agreements.”

He felt it defied the intention of this step, to check the assumptions based upon new information that arose from the “do” step.

Since the 1950s, PDCA has served to improve the production of high-quality products to optimize the chances to create value. It all started in Japan, where the training from Deming had a profound impact.

One of the most famous examples of this impact of Deming is the birth of the Toyota Production System (TPS). TPS helped make Toyota the leading car manufacturer in the world. Since then TPS (or lean manufacturing) has been widely adopted all over the world.

One of the key factors of TPS is Kaizen, a concept that embraces continuous improvement. The improvement cycle of Kaizen is called PDCA. The link to Deming and Shewart can’t be more direct!

“Eighty-five percent of the reasons for failure are deficiencies in the systems and process rather than the employee. The role of management is to change the process rather than badgering individuals to do better.” — W. Edwards Deming

We learned that PDCA started as a way to improve manufacturing and production, on how to create the products. But these days, it is at least as relevant to use PDCA to understand what to create.

We live in a fast-changing world. What we believe to be top-tier today may be out-of-date in a few months. This is certainly true in the field of product management. We don’t have the luxury of designing a product and working on it for months or years without frequently checking our assumptions and adjusting our course.

“In today’s fast-paced, fiercely competitive world of commercial new product development, speed and flexibility are essential. Companies are increasingly realizing that the old, sequential approach to developing new products simply won’t get the job done.” — Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka (“The New New Product Development Game,” 1986)

In fact, the world changes faster and faster and developments can be highly disruptive. Examples are:

All of this may make it impossible to now know what you will need to create a year from now. Just think of the iPhone and how it disrupted the mobile phone market in 2007. And think of ChatGPT and how it changed the way you find information on the internet today. What will be the big thing a year from now?

PDCA helps to deal with these uncertainties. It allows us to define a goal, take small controlled steps, check progress towards the goal, and act by adjusting course to optimize the chances to meet the goal. With that, it has offered a way to mitigate the risks of ever-changing requirements. In fact, PDCA embraces uncertainty.

PDCA allows us to have small experiments to understand quickly whether a particular idea has merit. Before you are going to invest heavily in a product solution, you better know if it makes sense to do so. And when to stop. The continuous PDCA cycle is helping to figure this out.

Suppose that you have 10 different new product ideas. They are all promising, but you don’t have the time, resources, and money to invest heavily in all of them. Using PDCA, you can run experiments to verify the validity and promise of each individual idea. You start with (plan)ning how you can verify the validity of a product idea as quickly as possible. Then you (do) this plan, (check) the results and learn from it to understand what to do next (act). With PDCA, you focus on removing the highest risks. In this case, the unclarity is whether an idea indeed has promise.

But PDCA doesn’t only help you to decide what product to invest in. It also helps to create a product. Through the lifecycle of the product, it helps you to focus on what you think will bring the highest value first, verify that, and then build upon that. It helps you to organically grow a product.

Without PDCA, we would not have agile. All agile approaches have their own learning loop, for example:

With PDCA engrained in all agile approaches, many in product management are already using it without knowing. Scrum even has three different PDCA cycles:

On top of the PDCA-inspired learning cycle, the agile approaches also emphasize customer collaboration, quality of work, and teamwork. With that, these approaches offer us solid guidelines to introduce and foster a learning mindset in the organization.

PDCA is everywhere in our modern world, whether we realize it or not. It is part of lean manufacturing, Lean Six Sigma process improvement, and agile approaches. Whenever you implement one of these approaches, you also implement PDCA.

Crucial elements are a(n):

Everyone should have this: product managers, the product teams, the organization as a whole, and the customers and users.

Organizations should manage on the desired outcome and not solely on the planned output. The feature you create should bring you the desired outcome. The outcome is what matters in the end.

People should not be afraid of bad news. Experiments can have unexpected undesired results. These are just as valuable for learning as expected positive results. It is what you do with these learnings that matters.

People need to collaborate to achieve results. All information needs to be on the table to make the best possible decisions.

Many teams and organizations that claim to use agile product management approaches are not “agile” at all. And the aspect that is missing most of the time is the learning loop and everything it entails. This is why PDCA can help you understand your own agile adoption. With PDCA in mind, you can ask the questions:

Plan-do-check-act (PDCA) took the world by storm as part of the Toyota Production System and lean manufacturing. Nowadays, it also is vital in all agile product management approaches. The agile premise of working in short iterations to create a working product increment and learning from feedback to understand what to best do next is essentially PDCA.

Agile approaches may evolve and perhaps even fade away. But the PDCA cycle is bound to stay as a crucial element to work in short iterations towards your goals.

Featured image source: IconScout

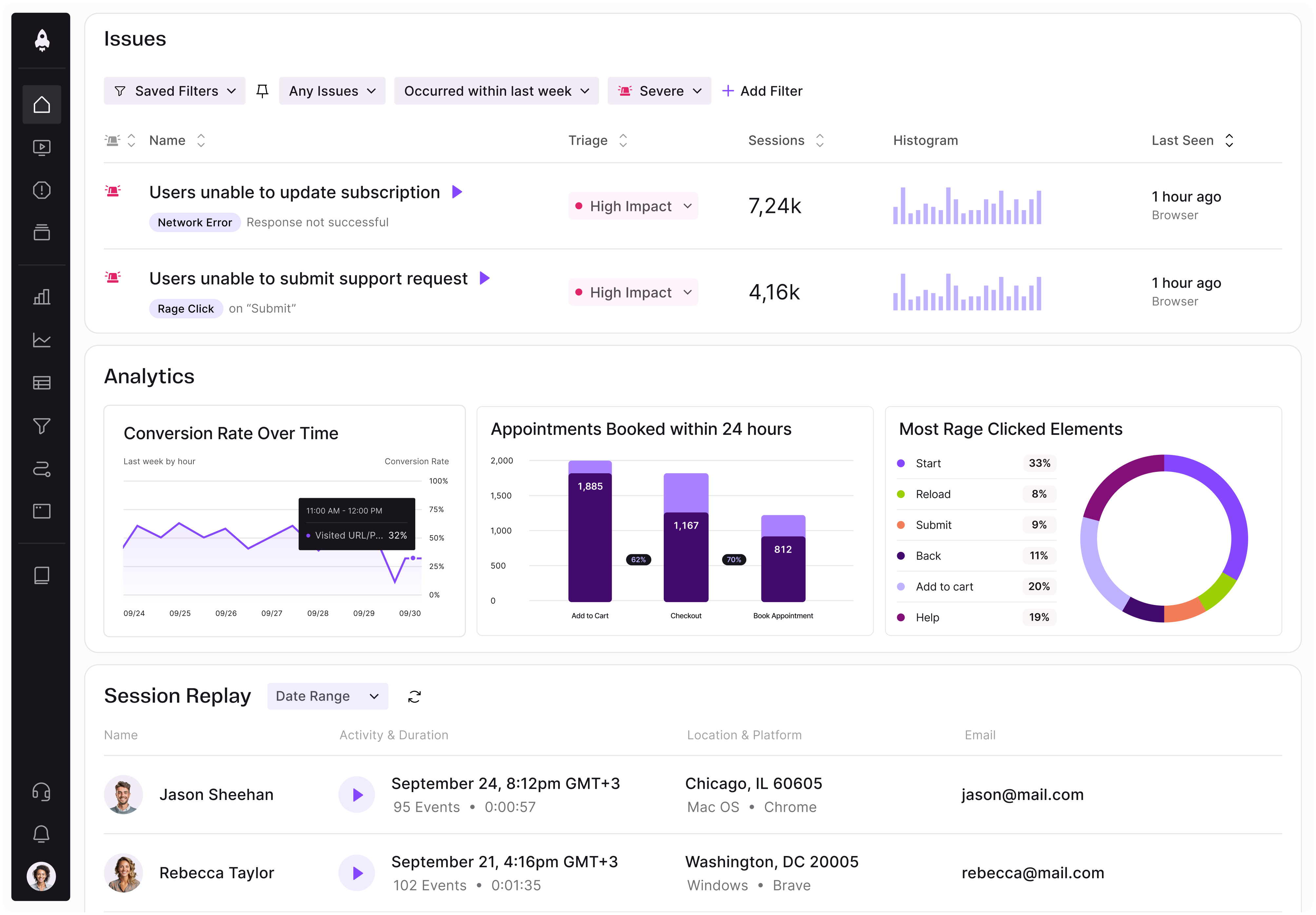

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.