You don’t need to come up with fresh product ideas to create successful products. Plenty of businesses create successful products that essentially already exist by leveraging competitive advantages, and these competitive advantages can be related to features, user experience, pricing and so on, while the products are otherwise clones of other products.

That’s right, imitation can be just as successful as innovation. In fact, people often don’t want innovation at all. Often, what they want is the best parts of what multiple products are already offering with few or no innovative features at all.

In this article, you’ll learn how to create products that essentially already exist, how to think of imitation as a good thing, what research methods you can use to help you decide between imitation and innovation, and how to market imitation as a selling point. I’ll also mention some cognitive biases and fallacies to provide insight into why businesses sometimes value innovation and why people sometimes value the same old, irrationally or otherwise.

First of all, imitating, copying, and even cloning — whatever you want to call it — isn’t a bad thing.

Your competitors are your competitors because they have something that’s worth copying, so choosing not to is like saying that you don’t have competitors. Step one is simply acknowledging that your competitors are your competitors for a reason and that you can learn from them. This’ll enable you to adopt a competitive attitude towards rival products more consciously, which in turn will enable you to be more proactive and more purposeful about creating a competitive product.

These days, you’d have a hard time creating a product that doesn’t already exist anyway.

But why are many businesses so pro-innovation?

The irrational belief that innovative products are inherently better is called pro-innovation bias. This cognitive bias causes businesses to innovate when it doesn’t make their product better (more advanced perhaps, or cooler, or just different, but not better necessarily).

Reluctance to take inspiration can also come down to ego, where a lack of original ideas can make one seem less intelligent and/or less capable. In reality though, being open to copying is smart business practice, so if you have a negative attitude towards it I recommend reframing it as competing.

That said, sometimes it’s time for a change, so this is in no way me saying that innovation is bad. Entertainment, healthcare, dating, banking, deliveries, and ordering are just a handful of the areas that have improved significantly because of innovation. However, this doesn’t change the fact that people are more often than not reluctant to try new things, will avoid doing so if they can, and might even prefer an inferior product just because it’s familiar.

Familiarity heuristic causes bias towards what’s familiar when what’s unfamiliar feels uncomfortable, and this bias is stronger when experiencing heavy cognitive load. For example, convincing somebody that eats apples to eat oranges instead (something that isn’t even better necessarily) might not be so difficult, but convincing them to learn an objectively more efficient method of filing taxes could take some work

Even users that do end up entertaining new ideas can end up reverting back to the same old because it’s familiar, which is why even innovative products should aim to be as familiar as possible.

As you may have surmised already, the key to product success isn’t using research to identify the best solution, it’s using research to identify what users want whether it’s rational or not, because although you can lead a horse to water, you can’t make it drink. Instead, try to understand how users evaluate the trade-off between quality and familiarity with different product ideas, and how far you can push users in terms of innovation.

You don’t really need to do anything specific to find out what to imitate and what to innovate as you’ll uncover this naturally during market, product, and UX research, but here’s where you’ll uncover most of the insights.

You can use competitive advantage surveys to gain a competitive edge over your rivals by finding holes in their products, and if you have a product on the market already, where your product is going wrong. However, it’s just as important to understand what other products are doing right too, so that you can implement the things that potential customers like about your competitor’s products and retain the things that customers like about your product.

When product teams get together (when running design sprints for example), they typically end up creating a low-fidelity prototype of what was voted as the best solution. This approach sounds great on paper; however, if users are already using a different solution they’re going to have formed an attachment to it whether it’s the best solution or not. Your perspective as a product team won’t necessarily match up with theirs.

For this reason, when user testing low-fidelity prototypes of innovative ideas, collect a mix of qualitative and quantitative data and compare it to that of a prototype that resembles what users might be using already. This will reveal how much you can realistically get away with in terms of innovation. You can then strike the right balance in a follow-up prototype. The goal isn’t to assess the acceptance of your best solution but rather the preference between all solutions.

Conceptually, this isn’t too different from competitive advantage surveys. The difference is that low-fidelity prototypes are tangible, so you’ll get user insights (the how) as well as product insights (the what). I recommend starting with competitive advantage surveys because they’ll provide enough validation to warrant spending resources on creating prototypes and conducting user tests.

When user testing prototypes (more so mid-fidelity and high-fidelity prototypes), pay extra attention to the words that participants use. “Same” and anything of the sort can have a negative meaning, whereas “familiar” or “what I’m used to” is more positive. It’s easy to misunderstand what participants mean though, which can set you down the wrong path, so ask them to clarify what they think and feel if you’re unsure.

Marketing the same old is incredibly easy because the same old is usually what customers prefer. The problem with a lot of products is that businesses, with their cognitive biases and fallacies, prefer to present a more innovative narrative because of the negative connotations sometimes associated with copying, but this is often harmful to product success. If you think about some of the businesses that market familiarity as a selling point, you don’t actually get negative vibes from them at all.

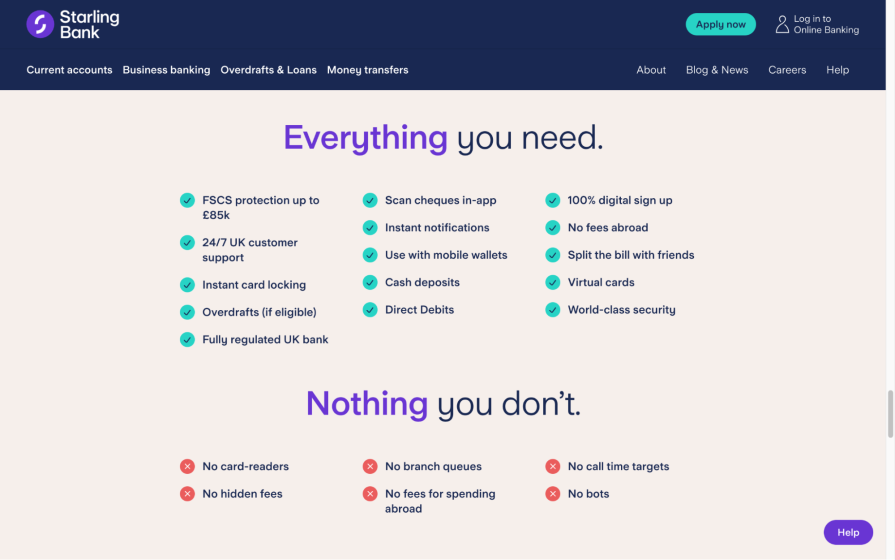

Digital-only banks are a great example of this. They take a modernized approach to banking but have the same features and level of security as traditional banks; they’re marketed as the same but better. For example, Wise often makes comparisons to high-street banks in regards to their fees, although Starling’s less on-the-nose approach is fine too:

So don’t be afraid to say something along the lines of, “You know that great product you love? Well this is just like it but better.”

As we’ve discussed throughout this article, even the best innovations can have trouble with product adoption because they lack familiarity. Well, unfortunately, you can’t really make innovation familiar, it just becomes familiar over time. The trick is to introduce innovative qualities gradually whenever possible to avoid putting a product out there that people aren’t ready for.

Products like this are sometimes considered ahead of their time and don’t do well, at least initially. Other times, being a bit pushy with new ways of doing things can impact your business negatively in the short run but bring about positive change faster. It really comes down to how risky your business can afford to be, and perhaps how old your customers are (younger people are often more adaptable to change than older people).

If mixing innovation into imitation gradually isn’t a viable solution then let users do things the old-school way too. For example, restaurants that offer ordering via a QR code/digital menu could offer traditional table service until the practice phases itself out naturally.

Finally, people are likely to believe that something is good just because it’s been described to them that way before, even without context or memory of where they heard it. This is called the illusory truth effect (or illusion-of-truth effect) and it’s how people know that Disneyland is “the happiest place on Earth” despite perhaps not being interested in Disney or theme parks at all. This means that newer stuff (in any sense of the word) will always be at a disadvantage. To combat this, consistency is key — just keep putting your brand messaging out there.

The main takeaway here is that there’s nothing wrong with products that borrow from other products. In fact, innovative products (while exciting and maybe even superior) can be daunting to adopt. Adapting to unfamiliar concepts requires time, energy, perhaps even resources. Collaborative tools might require any number of these from everybody at once.

On the other hand, innovation on the whole is necessary. Consumer needs change and often so must the products that address those needs. Eventually, anyway.

To get a better understanding of what your audience truly wants — imitation, innovation, or a mix of both — going through the usual motions of market/product/UX research will get you there for the most part, but you have to be unashamedly open to copying while doing it.

Good luck, thanks for reading, and as usual if you have any questions drop them into the comment section below!

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.

How AI reshaped product management in 2025 and what PMs must rethink in 2026 to stay effective in a rapidly changing product landscape.

Deepika Manglani, VP of Product at the LA Times, talks about how she’s bringing the 140-year-old institution into the future.