The way you do customer segmentation can make or break your product.

If you do it well, you can tailor your value proposition, packaging, and pricing to win the hearts of a well-defined group of customers. Do it poorly, and you’ll end up with a product that no one likes.

Segmentation brings focus. A product for everyone is a product for no one. The more you focus on a specific segment, the higher the chance of actually winning and dominating that segment.

At the end of the day, it’s better to win a smaller but well-defined part of the market than to strive to satisfy everyone.

The latter is impossible. Don’t even try.

Let’s first define what constitutes a good customer segment. After all, there are hundreds of possible ways and criteria to segment people. You could even segment people by the color of their underwear. That would be concerning, though.

There are two core characteristics of a good segment. A good segment should be:

An ideal segment would also be self-referencing — meaning people in the segment tend to recommend products to one another.

In other words, proper market segmentation allows you to act differently on different segments.

If you can’t do that, why even bother?

Segmentation by demographic data, such as gender, nationality, age, etc., is still among the most popular approaches. Mostly because it’s the most straightforward criterion.

It’s also the stupidest.

Let’s take a look at the characteristics of a good segment again. Ask yourself, if you segment by age and gender, is such a segment:

Luckily, there are better ways to identify criteria for segmentation. My favorite approach to defining user segments involves the following three steps:

Nothing connects people better than experiencing common pain points. Pains don’t differentiate by age, gender, or anything else.

You can have a 9-year-old child, an 80-year-old grandma, and a 35-year-old corporate worker experiencing the same pain point and having the same need, albeit for different reasons.

For example, the child might want to improve their English grammar skills to ace a test in school. The corporate worker might want to sound professional. And the grandma might have problems remembering the proper structures.

Although they are of entirely different demographics, a common need makes them a relatively homogenous group.

One need can be satisfied by many solutions. Understanding how valuable people find a given type of solution is another great way to segment or further the subsegment of the user base.

For example, there might be a significant group of people experiencing a pain point associated with their daily commute. The segment is not homogeneous enough, though. There’ll probably be a subgroup of people that:

Although these customers experience the same pain, they value different solutions differently. Therefore, they should be treated as separate segments. You have to act differently to win these different groups.

A truly homogenous and self-referencing segment is one that’s willing to pay similar money for similar features.

Back to our commute example: say you have defined a group of people who experience the pain of daily commuting. You decide to narrow down the focus to the ones who want to commute on their own while avoiding mass transit. There’s still one critical factor left on the table: different people are willing to pay different amounts to have the problem fixed.

You will probably find people willing to pay a lot just to make their commute more enjoyable. You could satisfy these people with some premium electric bikes, for example. But there’ll also be a more frugal group of people who can’t afford such a bike. A monthly electric scooter subscription might be a more suitable solution for them. And so on, and so on.

If you can’t win the segment in a similar manner, then it’s too heterogeneous. Narrow it down by treating groups with different willingness to pay as different (sub)segments.

If you follow the criteria I proposed and segment by pains, perceived value, and willingness to pay, you will end up with more than one segment — in other words, you will end up with too many segments.

This is one of those good problems to have; it’s better to have 20 well-defined, actionable user segments than one vague, massive segment. But how do you decide which segment to focus on first?

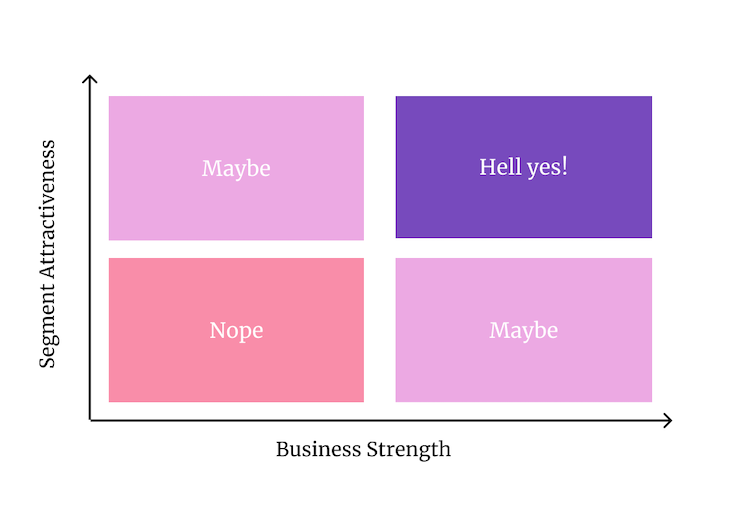

There are two criteria worth considering:

How attractive is the segment? How much value can you capture by catering to the needs of a specific segment?

Some criteria to evaluate segment attractiveness include:

How well is your company positioned to tackle the specific segment? Depending on your current business model, some segments might be easier to enter than others.

You can assess business strength by looking at your:

Segments that are both attractive and easily winnable are your best bets. As a second priority, choose either the most attractive (big bets) or most winnable (minor optimizations) ones. Ignore the rest.

Proper segmenting brings you focus. In the end, it’s better to win one or two small segments than do so-so in one big segment.

A good segment is homogenous, targetable, and self-referencing. Although demographic segmentation is the most straightforward approach, it doesn’t meet the characteristics of a good segment. In most cases, it’s just useless.

To select your next customer segment, you can use this four-step framework:

When in doubt, subsegment further. It’s very rare to define too narrow a segment. More often than not, people define broad, unactionable segments.

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Jim Naylor shares he views documentation as a company’s IP and how his teams should use it as a source of truth.

Act fast or play it safe? Product managers face this daily. Here’s a smarter way to balance risk, speed, and responsibility.

Emmett Ryan shares how introducing agile processes at C.H. Robinson improved accuracy of project estimations and overall qualitative feedback.

Suvrat Joshi shares the importance of viewing trade-off decisions in product management more like a balance than a compromise.