Most businesses are secretive. However, building products in the open can be beneficial.

In this article, you’ll learn what the benefits are and how to maximize them.

Building products in the open means being transparent about the aspects of a business that are traditionally kept private. This includes its processes, tools, learnings, mistakes, revenue, expenditures, and so on.

Building in the open is a modern way of engaging with customers, potential customers, and other interested audiences.

Businesses in the arts and entertainment space often share behind-the-scenes content, which is designed to engage their audience and nurture the bond between audience and the business. It’s like opening up to a friend.

Corporate businesses tend to front content in the form of tutorials and case studies, which are useful for marketing (i.e., helping businesses to be seen) and branding (i.e., helping them to be seen as industry leaders). Great examples include Airbnb Design, Slack Design, Dropbox Design, Adobe Design, and Designing Atlassian (Atlassian has also made its design system public).

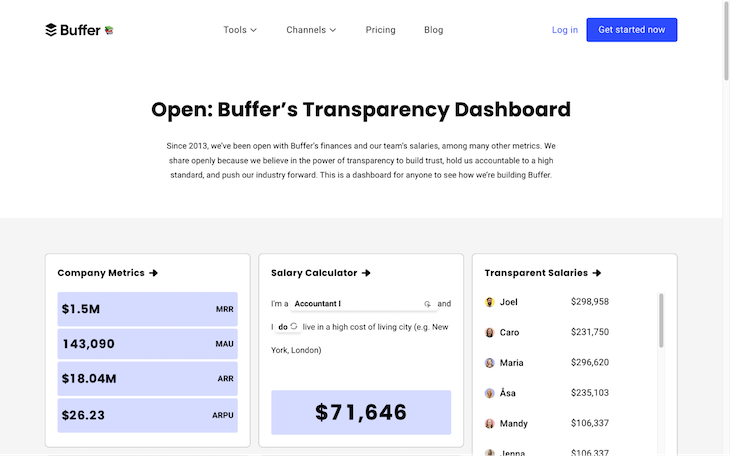

Buffer is open about its salaries, time off taken, how distributed its team is, and the outcomes of its experiments, such as its four-day week experiment:

Some businesses are open about their revenue and expenditures too. All of this builds trust.

First and foremost is the marketing value. In the short term, building products in the open can translate to early adopters (which also helps to validate or invalidate the product/product feature). It can also translate to increased marketing reach, which eventually leads to the same thing.

Secondly, building products in the open facilitates access to casual feedback and cheaper/easier recruitment of participants for less casual research.

Thirdly, detailing any victories or setbacks is great for branding. Detailing how the business leveled up (even if it was as a result of making mistakes) portrays it as an industry leader, shows eagerness to address problems, and builds trust. It also makes for great educational content for curious professionals — which, again, can translate to increased marketing reach.

Finally, building products in the open creates accountability — which isn’t necessarily a band aid for unproductiveness, but it can motivate businesses to make progress.

Building products in the open means being accountable. This means not following through with what you said you were going to do will leave a bad impression.

While this is supposed to be motivating, some actually find it daunting once the novelty of building in the open wears off for them, especially if they promised to document and present their progress. Therefore, building products in the open can tank the productivity of those who just aren’t into it.

On the other end of the spectrum, monitoring engagement from building a product in the open can be distracting and even addictive. In addition, sometimes the engagement is just vanity engagement with no marketing value at all, therefore the validation is just vanity validation that doesn’t translate to sales.

Building in the open also means being open to your competitors. It’s a literal do’s and don’ts guide to replicating your success, and this is the main reason why building products in the open will never become the mainstream way of working.

For products with unique attributes in particular, being ‘the first’ is a highly coveted sustainable competitive advantage, so secrecy is a must-have.

As you can see, there are many benefits to building in the open. However, there are a few unavoidable downsides too.

In this section, I’ll explain how different types of businesses can build in the open despite these downsides, and which benefits they can and can’t activate from doing so.

To answer the question more directly, though, anyone can build in the open. However, to what degree depends on the product and those building it.

Very few organizations are fully open. Many consider it too risky, with only a handful having such a strong market position that the rewards outweigh the risks.

The most prominent example is probably Buffer — Buffer has been open about all aspects of its business at some point or another.

For most organizations though, the risk of a competitive counteract is just too high, which limits what they can share or when they can share it. Although this means missing out on some of the benefits, it shouldn’t stop product teams from being open post-launch, at the very least.

Organizations that are semi-open don’t share everything, and anything that they do share is shared post-launch. This prevents competitors from beating them to the punch or countering them in some way. But it sacrifices the ability to build anticipation, which, unfortunately is a valuable advantage to have when launching a product. It also makes acquiring feedback more difficult.

Solopreneurs are those who build products by themselves; they’re not part of any organization. Makers are a modern-ish subculture of solopreneurs who are fairly open about their products, their product development process, and their revenue. Many makers are a part of the open startup movement, of which very few organizations are a part despite the movement being pioneered by an organization (you guessed it — Buffer!).

Makers aren’t slowed down by organizational workflows and bureaucracy, and also tend to have a wide range of design and development skills, so they’re able to build relatively quickly. This gives them more legroom to make mistakes and makes it difficult for competitors to react.

Makers also tend to have fewer overheads and are even able to utilize free feedback from their engaged fanbases, saving money on traditional research methods, which can be more expensive.

As an added benefit, having a good reputation for being knowledgeable, friendly, and building great products means they can build a personal brand as well as an identity for their products.

It’s worth noting that these are not two distinctive categories. Organizations (usually smaller ones) can build in public if they think they’re in a position to do so, and makers can build in private. It depends somewhat on their market position and the speed at which they’re able to ship, but it comes down to personal preference too.

An ideal primary goal of building in the open is to get early adopters. This provides your build in public journey with a measurable goal, enables you to drop what isn’t objectively working (including the product itself, if necessary), and, ultimately, focuses on actually building as much as possible.

The goal shouldn’t be related to page views, social media engagement, or any other vanity metrics — just how many people are, for example, pre-ordering or converting from closed betas.

Casual feedback doesn’t necessarily replace traditional research. However, you can find better research participants by building products in the open.

Instead of screening and paying for participants that fit the persona of your users, building products in the open enables you to recruit your actual users. In my opinion, this is the greatest benefit to building in the open.

I recommend investing in ResearchOps — in particular, establishing a process and setting up a workflow for conducting research with research participants sourced via social media and the like.

That said, it’s perfectly fine to accept feedback made in response to whatever you’ve been open about. In fact, you can publicly ask for it and even use it as a jumping-off point for more formal customer interviews.

The branding-related benefits from being open about successes and hurdles are subtle (as the effects of branding usually are), so building in public for this reason might not seem like a top concern. However, building trust through transparency is very important.

I don’t have any specific advice regarding this other than be genuine — don’t be selectively transparent to portray a fake narrative, as that would produce the exact opposite effect.

If you’re keen to embrace building in public as a product team, it’s important to foster a culture where everyone is open to present a complete and coherent story. This can be difficult because some people just won’t want to partake in this due to introvertism or simply being busy.

For this reason, it’s usually better to nominate certain passionate individuals to take on the responsibility of creating content to share publicly. This enables those uninterested in being open to share the necessary details with said content creators rather than the public itself.

While building products in the open has some drawbacks, there are ways for businesses of all types to embrace it on some level at least.

It’s true that the maker community has evangelized building in publi, as there are certainly many failed products out there bootstrapped by solo founders that could have been saved by utilizing more traditional processes. On the other hand, many product and UX experts also evangelize product/UX processes in the same way, often refusing to admit that some processes — such as personas are a waste of time, and also that some research methods (e.g. just asking users) — might be cheaper and more accessible than more traditional methods (e.g. performance testing) and thus make more business sense overall.

In reality, the best approach is to embrace both as needed, as the case with most things.

The same could be said for transparency: while building products in the open often causes solopreneurs to become focused on engagement metrics rather than actually generating revenue, many organizations are so disconnected from their customers that it’s not uncommon to see a product launch/change and think, who asked for this?

All in all, you should consider the benefits and downsides of building products in the open very carefully and go with whatever feels right for you/your team/your business.

If you have a question or anything to add, leave a comment. Thanks for reading!

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

How AI reshaped product management in 2025 and what PMs must rethink in 2026 to stay effective in a rapidly changing product landscape.

Deepika Manglani, VP of Product at the LA Times, talks about how she’s bringing the 140-year-old institution into the future.

Burnout often starts with good intentions. How product managers can stop being the bottleneck and lead with focus.

Should PMs iterate or reinvent? Learn when small updates work, when bold change is needed, and how Slack and Adobe chose the right path.