One of the advantages of the Rust programming language is that it’s designed to be high performance. In fact, under “Why Rust?” on the Rust website, the first answer is “Performance”!

Arena allocation is a mechanism that can be used in many languages, including Rust, to further improve the performance of memory allocation and deallocation. In this guide, we will cover:

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

An arena allocator, also simply known as an arena, is an object you can use to allocate a series of objects that all have relatively short lifetimes. This strategy is known as region-based memory management.

Arenas are also called regions, zones, areas, or memory contexts.

Typically, when the arena is constructed, a block of memory is reserved from the system. The arena then sets up a pointer to the next free position in that block of memory, which is initialized to the beginning of that space.

When a request is made to allocate memory from the arena, it simply returns the pointer to the next free position and increments the pointer past the just-returned allocation. After the program is done with all of the objects, the entire underlying block of memory is freed.

Typically, for even better performance, no destructors are run on the objects in an arena, which prevents unnecessary work. However, some arenas do provide ways to run destructors on some objects if necessary for your use case. See the specific use case examples below to learn more.

Both allocation and deallocation of an arena are much faster than allocating and deallocating multiple small objects from the system individually. There is also a cache benefit because objects that are all being used at the same time are close together in memory.

The only restriction is that it isn’t easy to individually deallocate objects in the same arena. As a result, it makes the most sense to use an arena if multiple objects need to be allocated and used during the same or a similar timeframe, after which none of them are needed anymore.

There are many cases where using an arena can improve the performance of your application. Let’s review three common examples: games, compilers, and web servers.

For games that are rendered a frame at a time, each frame can have an arena associated with it. Using this strategy, all objects necessary to render that frame can be allocated from the arena.

When the frame is done rendering, none of those objects are needed anymore, so the whole arena can be deallocated.

The different phases of a compiler are generally independent, so intermediate objects for each phase can be allocated from an arena. When each phase is done, the whole associated arena can be deallocated.

Web requests have a well-defined lifetime. If responding to a web request requires a large number of allocations to calculate a response, these can be made from an arena. The arena can then be deallocated once the request is complete, which helps improve performance.

Data structures that have elements pointing to other elements are notoriously hard to implement and use in Rust. Seriously — there’s a whole book about implementing various linked lists in Rust!

This is because of the Rust borrow checker, an essential fixture of this language that helps you manage ownership.

Using arenas in Rust can make it easier to have elements that point to each other in a cyclic way because in an arena, the lifetime of every element is the same as the arena’s lifetime.

If you look on crates.io, you can find many good choices for implementing arenas in Rust. Let’s take a look at a few of the most popular ones!

bumpalo arena allocatorbumpalo is the most downloaded arena allocator on crates.io. It’s pretty easy to use. Here’s an example:

struct SomeData {

name: String,

value: u32

}

fn bumpalo_example() {

// Note that arena needs to be declared mutable

// so we can call reset() on it below.

let mut arena = bumpalo::Bump::new();

for _ in 0..10 {

let data1: &mut SomeData = arena.alloc(SomeData {

name: "some data".to_string(),

value: 1

});

let data2: &mut String = arena.alloc(String::from("some more data"));

// use data1 and data2 here, now we're all done

// We can call arena.reset() to free all the memory and start fresh

// This also invalidates data1 and data2, so the compiler won't let us

// use them anymore.

arena.reset();

}

}

bumpalo supports allocating any kind of object. By default, it does not run destructors (i.e., Drop implementations) on allocated objects. If you want to make an object run its Drop implementations, you can wrap it in a bumpalo::boxed::Box<T>.

Note that doing this prevents that object from being in a cycle, so this won’t work if you need to run Drop implementations on a cyclic data structure, such as a graph with nodes.

typed-arena arena allocatorAnother popular arena crate is typed-arena. Here’s an example of how to use it:

struct SomeData {

name: String,

value: u32

}

fn typedarena_example()

{

for _ in 0..10 {

let arena: typed_arena::Arena<SomeData> = typed_arena::Arena::new();

let data1: &mut SomeData = arena.alloc(SomeData {

name: "some data".to_string(),

value: 1

});

let data2: &mut SomeData = arena.alloc(SomeData {

name: "some more data".to_string(),

value: 2

});

// use data1 and data2 here, now we're all done

// There is no explicit way to reset the arena, but when it goes

// out of scope all of its memory will be freed.

}

}

As the name implies, each typed_arena::Arena only supports allocating one type of object. This is more limited than bumpalo, but makes the implementation simpler. It also allows easy access to the contents of the entire arena with the into_vec() method.

Note that typed-arena allocators do run Drop implementations for allocated objects.

id_arena arena allocatorid_arena has a slightly different interface as compared to bumpalo or typed-arena. Here’s an example:

struct SomeData {

name: String,

value: u32

}

fn idarena_example()

{

for _ in 0..10 {

let mut arena: id_arena::Arena<SomeData> = id_arena::Arena::new();

let data1_index: id_arena::Id<SomeData> = arena.alloc(SomeData {

name: "some data".to_string(),

value: 1

});

let data2_index: id_arena::Id<SomeData> = arena.alloc(SomeData {

name: "some more data".to_string(),

value: 2

});

// This will panic if data1_index has no associated data.

let data1: &SomeData = &arena[data1_index];

// get_mut() returns an Option, which will be None if data2_index

// has no associated data.

let data2: &mut SomeData = arena.get_mut(data2_index).unwrap();

// use data1 and data2 here, now we're all done

// There is no explicit way to reset the arena, but when it goes

// out of scope all of its memory will be freed.

}

}

Note that the call to arena.alloc() returns an id_arena::Id instead of a reference to the allocated data.

This is a bit more annoying to work with because you have to call another method to actually get the data. But it’s very handy if you’re working with cyclic data structures because you can just have objects hold on to the Id of other objects they refer to.

Like typed-arena, each arena in id_arena can only allocate one type of object. This arena allocator does run Drop implementations for allocated objects.

Another note: id_arena::Arena::new() allocates an empty Vec as its backing storage. This backing storage will expand as needed. However, it would be more efficient to create the arena this way instead:

id_arena::Arena::with_capacity()

This method allows you to pass in an initial capacity that is reasonable for your application.

generational-arena arena allocatorOn the surface, the generational-arena crate looks very similar to id_arena:

struct SomeData {

name: String,

value: u32

}

fn generationalarena_example() {

let mut arena: generational_arena::Arena<SomeData> = generational_arena::Arena::new();

for _ in 0..10 {

let data1_index: generational_arena::Index = arena.insert(SomeData {

name: "some data".to_string(),

value: 1

});

let data2_index: generational_arena::Index = arena.insert(SomeData {

name: "some more data".to_string(),

value: 2

});

// This will panic if data1_index has no associated data.

let data1: &SomeData = &arena[data1_index];

// get_mut() returns an Option, which will be None if data2_index

// has no associated data.

let data2: &mut SomeData = arena.get_mut(data2_index).unwrap();

// use data1 and data2 here, now we're all done

// There is no explicit way to reset the arena, but when it goes

// out of scope all of its memory will be freed.

arena.clear();

}

}

The big difference here is that this kind of arena allows deleting individual objects, which is unusual for an arena. However, this also means that there is more bookkeeping involved in the arena’s code, so it’s probably best to avoid using this crate unless you need this capability.

Like typed-arena and id_arena, each arena can only allocate one type of object. It does run Drop implementations for allocated objects.

Using an arena can greatly speed up allocating many objects in certain scenarios. They’re easy to try out in Rust by just including a crate. So, if you’re looking for ways to make your code run faster, give it a shot!

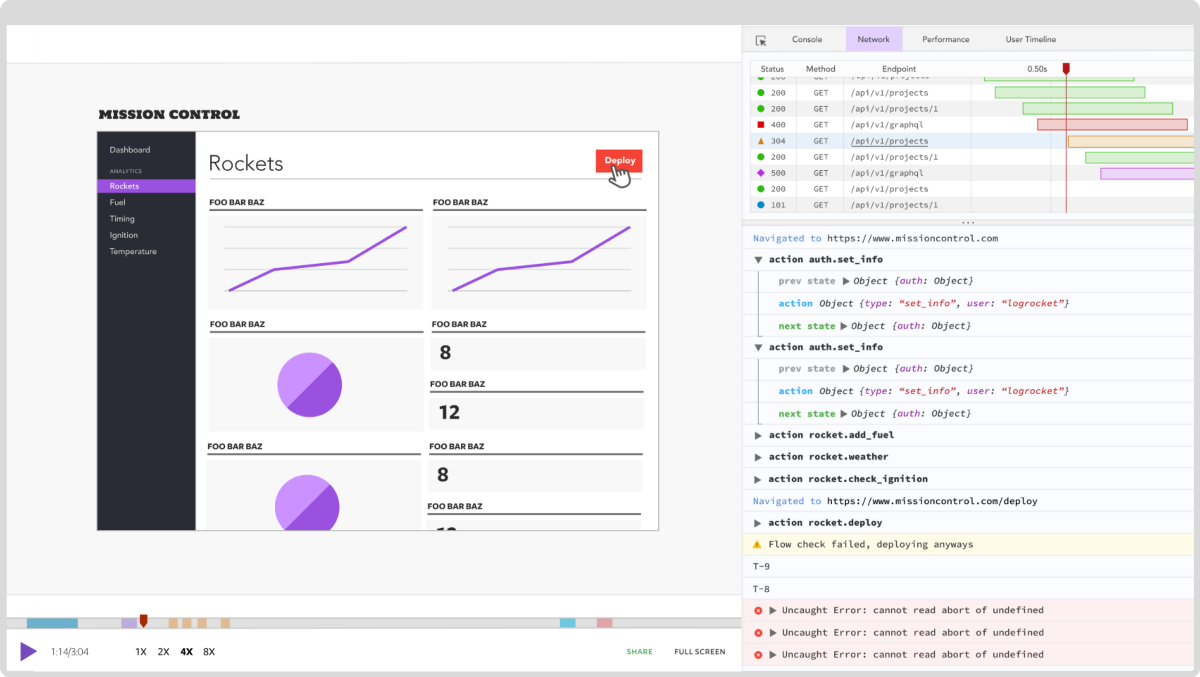

Debugging Rust applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are hard to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking the performance of your Rust apps, automatically surfacing errors, and tracking slow network requests and load time, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug your Rust apps — start monitoring for free.

React Server Components and the Next.js App Router enable streaming and smaller client bundles, but only when used correctly. This article explores six common mistakes that block streaming, bloat hydration, and create stale UI in production.

Gil Fink (SparXis CEO) joins PodRocket to break down today’s most common web rendering patterns: SSR, CSR, static rednering, and islands/resumability.

@container scroll-state: Replace JS scroll listeners nowCSS @container scroll-state lets you build sticky headers, snapping carousels, and scroll indicators without JavaScript. Here’s how to replace scroll listeners with clean, declarative state queries.

Explore 10 Web APIs that replace common JavaScript libraries and reduce npm dependencies, bundle size, and performance overhead.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now