Editor’s note: This article was last updated by Pascal Akunne on 6 June 2024 to discuss how the latest Node versions support ES modules and to offer a brief evolution of JavaScript modules, a timeline from IIFE to ES modules.

In modern software development, modules organize code into self-contained chunks that make up a larger, more complex application. In the browser JavaScript ecosystem, the use of JavaScript modules depends on the import and export statements; these statements load and export ECMAScript modules (or ES modules), respectively.

The ES module format is the official standard format to package JavaScript code for reuse, and most modern web browsers natively support the modules.

Node.js, however, supports the CommonJS module format by default. CommonJS modules load using require, and variables and functions export from a CommonJS module with module.exports.

The ES module format was introduced in Node.js v8.5.0 as the JavaScript module system was standardized. As an experimental module, the --experimental-modules flag was required to successfully run an ES module in a Node.js environment. However, Node.js has had stable support of ES modules since version 13.2.0.

This article won’t cover much about the usage of both module formats, but rather how CommonJS compares to ES modules and why you might want to use one over the other.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Before we jump into understanding the differences between CommonJS and ES modules’ syntax, let’s briefly explore the history and evolution of JavaScript modules.

JavaScript modules have evolved greatly over the years, starting with the IIFE, which prevents global pollution of the global scope and allows code encapsulation, to the Module pattern, which provides a clearer separation between private and public components of a module, solving the growing complexity in JavaScript applications. However, both the IIFEs and Module patterns did not have a standard way of managing dependencies, which necessitated better development solutions.

CommonJS was primarily intended for server-side development with Node.js. It implemented synchronous loading using require and module.exports. Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD), on the other hand, concentrates on browser environments with asynchronous loading using define and require, which improved page load time and responsiveness. Still, there was always a need for better solutions. The need for a solution that could function in both the server-side and browser environments prompted the development of Universal Module Definition (UMD).

Then came the ES modules, which provide a native module system for both client and server-side JavaScript. ES6 modules provide a clear syntax, import and export statements, and support for asynchronous loading. This progress has made code more maintainable, reusable, and performant, allowing developers to build more scalable applications.

There was no built-in module system in the early days of JavaScript. Codes were written in a global scope, rendering functions and variables accessible globally, resulting in naming conflicts and complex codebases. The lack of encapsulation and modularity made it difficult for developers to reuse code across multiple projects.

The evolution of JavaScript modules has resulted in a more organized and maintainable approach to writing code, allowing for the effective encapsulation and management of code dependencies.

By default, Node.js treats JavaScript code as CommonJS modules. Because of this, CommonJS modules are characterized by the require statement for module imports and module.exports for module exports.

For example, this is a CommonJS module that exports two functions:

module.exports.add = function(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

module.exports.subtract = function(a, b) {

return a - b;

}

We can also import the public functions into another Node.js script using require, just as we do here:

const {add, subtract} = require('./util')

console.log(add(5, 5)) // 10

console.log(subtract(10, 5)) // 5

If you are looking for a more in-depth tutorial on CommonJS modules, check this out.

On the other hand, library authors can also simply enable ES modules in a Node.js package by changing the file extensions from .js to .mjs.. For example, here’s a simple ES module (with an .mjs extension) exporting two functions for public use:

// util.mjs

export function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

export function subtract(a, b) {

return a - b;

}

We can then import both functions using the import statement:

// app.mjs

import {add, subtract} from './util.mjs'

console.log(add(5, 5)) // 10

console.log(subtract(10, 5)) // 5

Another way to enable ES modules in your project can be by adding a "type: module" field inside the nearest package.json file (the same folder as the package you’re making):

{

"name": "my-library",

"version": "1.0.0",

"type": "module",

// ...

}

With that inclusion, Node.js treats all files inside that package as ES modules, and you won’t have to change the file to a .mjs extension. You can learn more about ES modules here.

Alternatively, you can install and set up a transpiler like Babel to compile your ES module syntax down to CommonJS syntax. Projects like React and Vue support ES modules because they use Babel under the hood to compile the code.

The ES module format was created to standardize the JavaScript module system. It has become the standard format for encapsulating JavaScript code for reuse.

The CommonJS module system, on the other hand, is built into Node.js. Prior to the introduction of the ES module in Node.js, CommonJS was the standard for Node.js modules. As a result, there are many Node.js libraries and modules written with CommonJS.

For browser support, all major browsers support the ES module syntax and you can use import/export in frameworks like React and Vue.js. These frameworks use a transpiler like Babel to compile the import/export syntax down to require, which older Node.js versions natively support.

Apart from being the standard for JavaScript modules, the ES module syntax is also much more readable than require. Web developers who primarily write JavaScript on the client will have no issues working with Node.js modules, thanks to the identical syntax.

While ES modules have become the standard module format in JavaScript, developers should consider that older versions of Node.js lack support (specifically Node.js v9 and under). In other words, using ES modules renders an application incompatible with earlier versions of Node.js that only support CommonJS modules (i.e., the require syntax).

But with the new conditional exports, we can build dual-mode libraries. These are libraries that are composed of the newer ES modules but are also backward-compatible with the CommonJS module format supported by older Node.js versions. In other words, we can build a library that supports both import and require, allowing us to solve compatibility issues.

Consider the following Node.js project:

my-node-library ├── lib/ │ ├── browser-lib.js (iife format) │ ├── module-a.js (commonjs format) │ ├── module-a.mjs (es6 module format) │ └── private/ │ ├── module-b.js │ └── module-b.mjs ├── package.json └── …

Inside package.json, we can use the exports field to export the public module (module-a) in two different module formats while restricting access to the private module (module-b):

// package.json

{

"name": "my-library",

"exports": {

".": {

"browser": {

"default": "./lib/browser-module.js"

}

},

"module-a": {

"import": "./lib/module-a.mjs"

"require": "./lib/module-a.js"

}

}

}

By providing the following information about our my-library package, we can now use it anywhere it is supported, like so:

// For CommonJS

const moduleA = require('my-library/module-a')

// For ES6 Module

import moduleA from 'my-library/module-a'

// This will not work

const moduleA = require('my-library/lib/module-a')

import moduleA from 'my-awesome-lib/lib/public-module-a'

const moduleB = require('my-library/private/module-b')

import moduleB from 'my-library/private/module-b'

Because of the paths in exports, we can import (and require) our public modules without specifying absolute paths. By including paths for .js and .mjs, we can solve the issue of incompatibility; we can map package modules for different environments like the browser and Node.js while restricting access to private modules.

However, it’s important to remember that for Node.js to treat a module as an ES module, one of the following must happen: either the module’s file extension must convert from .js (for CommonJS) to .mjs (for ES modules) or we must set a {"type": "module"} field in the nearest package.json file.

In this case, all code in that package will be treated as ES modules and the import/export statements should be used instead of require.

In recent years, there have been released versions of Node.js that have shifted from the traditional CommonJS module system to the ES module system, allowing developers to use import and export natively within their Node.js projects.

This change improves the development experience for both client and server-side JavaScript, allowing for easier code sharing and reuse. There is also interoperability between ES modules and CommonJS modules, which allows developers to dynamically import CommonJS modules via the import function, ensuring that existing libraries and codebases continue to function during the transition to ES modules.

Also, the Node.js standard libraries (such as fs, http, and url) now support the ES module syntax, so developers can use native Node.js APIs via import statements. For example, you can import the fs module to use the promise-based API for asynchronous file operations.

In an ES module, the import statement can only be called at the beginning of the file. Calling it anywhere else automatically shifts the expression to the file beginning or can even throw an error. On the other hand, the require function gets parsed at runtime. As a result, require can be called anywhere in the code. You can use it to load modules conditionally or dynamically from if statements, conditional loops, and functions.

For example, you can call require inside a conditional statement like so:

if(user.length > 0){

const userDetails = require(‘./userDetails.js’);

// Do something ..

}

Here, we load a module called userDetails only if a user is present.

One of the limitations of using require is that it loads modules synchronously, which means that modules are loaded and processed one by one. A task can only begin once the preceding one is completed. This is known as “blocking” because if an operation takes a long time to complete, it prevents the following tasks from starting.

Sync code is simple to write and read, and it follows a threaded execution model, making it easier to predict the code flow and result. However, it can cause serious performance issues because sync loading can cause an entire application or program to freeze or become unresponsive, particularly in scenarios involving I/O operations, long computations, or real-time responsiveness, resulting in poor user experience and scalability.

In such a case, import might outperform require based on its asynchronous behavior. However, the synchronous nature of require might not be much of a problem for a small-scale application using a couple of modules.

On the other hand, asynchronous operations are normally carried out with callbacks, promises, or async/await syntax. Async code, unlike synchronous code, can be harder to read, write, and debug, because it is non-linear. But it provides a better user experience because it works well on high-traffic web apps that don’t have to wait their turn to run.

For developers who still use an older version of Node.js, adopting the new ES module would be impractical due to the limited support, which could render an application incompatible with earlier versions of Node.js.

However, for beginners, learning ES modules is beneficial as they are becoming the standard format for defining modules in JavaScript for both the client side and server side. For new Node.js projects, ES modules provide a good alternative to CommonJS. The ES modules format offers an easier route to writing isomorphic JavaScript, which can run in either the browser or on a server.

All in all, ECMAScript modules are the future of JavaScript.

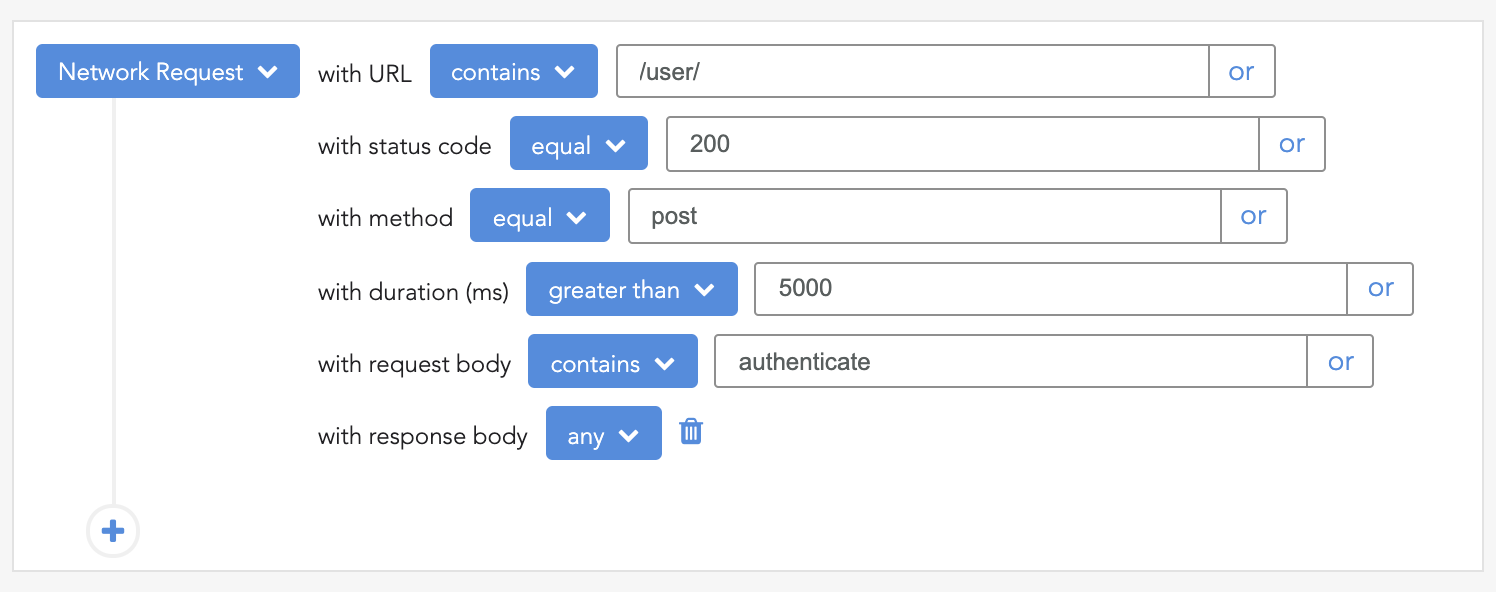

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

React Server Components and the Next.js App Router enable streaming and smaller client bundles, but only when used correctly. This article explores six common mistakes that block streaming, bloat hydration, and create stale UI in production.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

6 Replies to "CommonJS vs. ES modules in Node.js"

You are able to dynamically import es modules. You can for example out them inside an If statement, it just returns a promise.

Very nice and most informative article! 🙂 One minor I noticed (possibly a ‘typo’?): In the following section, I believe you meant to write: import {add, subtract} from ‘./util.mjs’, and not ‘./util.js’. Correct?

Link to that part of the article: https://blog.logrocket.com/commonjs-vs-es-modules-node-js/#:~:text=the%20import%20statement%3A-,//%20app.mjs,-import%20%7Badd%2C%20subtract

Very helpful article!

By default, you can import a cjs module into a esm script, but not the opposite – you cannot require a cjs module in a esm script, as the synchronous require will not wait for the async import to resolve.

This can be solved with https://www.npmjs.com/package/require-esm-in-cjs

how can I import this in ES module

var session = require(“express-session”);

var FileStore = require(“session-file-store”)(session);

hi