Sprint planning is an important scrum ceremony in which the scrum team decides what work it will commit to in the upcoming sprint. Whether your teams work in two- or four-week sprints, the sprint planning ceremony should take place at the beginning of each sprint.

In this guide, we’ll define sprint planning at a high level before diving into the details, including who participates in sprint planning, what occurs during the ceremony, and best practices for running a sprint planning meeting.

Scroll to the end to see a sprint planning meeting agenda template you can use as a cheat sheet when conducting your own sprint planning ceremony.

A sprint planning meeting is a session in which the product manager and development team plan the work the team will commit to for the upcoming 2–3 weeks.

Sprint planning meeting are usually full-day events for a month’s sprints but can be proportionately shorter for shorter sprints managed by a scrum master.

The sprint planning ceremony is usually led by the product manager, product owner, or scrum master. All members of the scrum team should be in attendance. This includes engineers, QAs, and designers, each of whom is critical to the sprint planning process.

In addition to leading the meeting, the product manager helps provide business or user context and prioritizes tradeoffs.

Designers can help clear up any last-minute confusion about designs and acceptance criteria.

Engineers define implementation complexity and how much work it can commit to. QA is also important in this regard. Just because a story is dev-complete doesn’t mean it can be released; there needs to be testing capacity too.

During sprint planning, the scrum team reviews work from the previous sprint, determines its capacity for the upcoming sprint, and commits to the highest-priority work to fill that capacity.

Begin by reviewing the work completed in the previous sprint. Were all the committed stories completed? If not, identify the amount of effort left on any stories or tasks that are rolling over. Taking these into account ensures you won’t overcommit to new work by approaching it as if you have full capacity (because you don’t).

Some notes on sprint rollover:

After you’ve assessed the work and effort rolling over, the team can discuss new stories to pull in. Again, as the product manager, you should define priority and provide context, but the rest of the team should decide how much of that it can complete.

Tradeoff decisions may need to be made during these discussions. This is where your product management skills are critical.

For example, let’s say you’re hoping to fit in a three-point and five-point story, but there’s only capacity left for five points. You can decide to pull in the five-pointer or opt for the three-pointer with another small story.

When faced with a scenario like this example, you should discuss the business, user, and technical tradeoffs with the team. Don’t delay any future work that’s blocked by the story you’re deprioritizing.

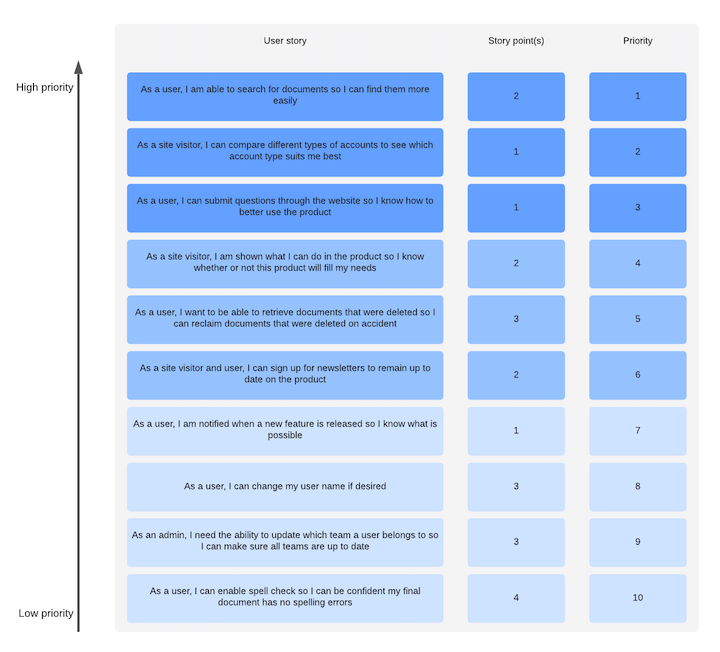

Below is a detailed example of a product backlog groomed and prioritized as a result of sprint planning:

Sprint goals originated in the early days of scrum as a way to measure success for each completed sprint. While some teams still hold sprint goals in high regard, they’re not always necessary. In some cases, they’re not even possible.

If you’re building a new product that may take several sprints to be MVP-ready, it’s tough to define useful sprint goals. It can be tempting to set a goal to deliver all committed stories in the sprint, but this puts your focus on output rather than outcomes.

As long as you’re prioritizing the most important work along the path to release and the entire team feels comfortable with each sprint’s commitments, you might be better off forgoing sprint goals altogether.

Sprint planning is more than just pulling stories into the to-do list until the team says “stop.” Let’s review some key considerations and best practices to help you commit to the highest quality and proper quantity of work while preemptively avoiding roadblocks.

Use sprint planning to decide what stories to commit to and don’t get lost in the weeds. Diving into the requirements for those stories and estimating how long they may take is a surefire way to derail sprint planning and trap the team in an unnecessarily long meeting.

The backlog grooming ceremony is a much better time to scope and estimate stories before they’re pulled into a sprint. This gives the team time and space to dig into the acceptance criteria and fully understand the effort without the added pressure of figuring it out immediately. This can also surface tradeoffs related to complexities or dependencies, which may need to be evaluated before estimating or committing to the work.

Estimating stories ahead of sprint planning can help you avoid sprint delays and unrealistic expectations.

Address as many unknowns as possible ahead of the sprint. This can often be done through grooming ceremonies, technical spikes, or other pre-work investigations. However, some unknowns are unavoidable until the actual work begins.

You should plan for these scenarios to avoid overcommitting to complicated work. The best way to do this is to account for these unknowns ahead of time when estimating stories during your grooming ceremony.

For example, if a story feels like it’s probably three points, it’s a good idea to overestimate the time it will take to account for unforeseen issues.

Dependencies are a catalyst for roadblocks if not coordinated ahead of time. And they can go both ways.

Maybe your team is building a feature that’s dependent on another team completing API updates. Or maybe the marketing team is waiting to launch a new email campaign and your team is working to build and release the associated landing page.

As a product manager, it’s your responsibility to coordinate and prioritize these dependencies with stakeholders or other product managers prior to bringing the work to sprint planning.

Knowing your team’s capacity for the work they can commit to is critical for successful planning. This should not be based solely on past sprint velocity because each sprint is different.

We already talked about accounting for sprint rollover when determining your capacity for each sprint, but there are other factors to weigh: Are there any holidays or vacations coming up? Are there company or department offsites? Does your company do dev days for non-sprint related pursuits? All of these considerations are important in understanding your true capacity.

Unplanned work can arise in the middle of a sprint and set your commitments off track, but it doesn’t have to be that way. As a product manager, it’s your job to assess and decide whether something is important enough to be pulled into the in-progress sprint.

This isn’t to say you should leave capacity open on the off-chance that something arises, but you should head into the sprint knowing that some of the committed work could potentially be sidelined by unplanned work.

There are three main types of unplanned work you may encounter:

Running an effective sprint planning begins with intentional and upfront preparation.

Prior to planning, you should have a clear idea of what you hope to achieve in the sprint. Early steps include product discovery, research, user testing, and other methods to determine the most impactful work. If you’re walking into sprint planning with a new idea you haven’t properly vetted, that is potentially a recipe for disaster.

You should also ensure the work is truly ready to go. Have the tickets been groomed and prioritized by impact or urgency? Have the necessary spikes, tradeoffs, and dependencies all been addressed?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, consider whether the work is truly ready for development. In some cases, a “no” may be unavoidable (e.g., a last-minute bug that should be addressed but hasn’t been scoped yet), but this usually isn’t the case.

Once you’ve prepared for sprint planning, it’s time to run the meeting. We’ve already discussed how to determine capacity based on rollover work, resource availability, and other factors, which are all important to running a successful sprint planning.

If there’s a single golden rule for product managers to effectively run a sprint planning, it’s this: listen to your team. Developers know their capacity and understand the complexity of the work you’re discussing. Don’t push or challenge their expertise. If they say they can commit to no more than 20 points, don’t push or persuade them to increase it to 25.

Worst case scenario, you miss your sprint commitments and lose trust among your team. Best case scenario, you hit all your deadlines and your team still doesn’t trust you. You should be leading, not dictating.

Sometimes, this means the stories you had planned for during preparation don’t all make it in. If you’re in tune with your team’s work and typical velocity, your wish list should be pretty close to the actual result, but don’t be frustrated if the stars don’t all align.

If you’re listening to your team, considering capacity, willing to make tradeoffs or scope cuts, doing the upfront work for dependencies and prioritization, and understand the acceptance criteria in and out to help answer questions, your sprint planning should be a success.

As described above, a lot goes into leading successful sprint planning meetings. The sprint planning meeting agenda template below is designed to help you keep track of the most important items to achieve that success.

Stories are groomed, estimated, and ready to be worked on

Dependencies are coordinated with other teams and/or stakeholders

Backlog is prioritized by accounting for impact, urgency, dependencies, and blockers

Review work that was completed and shipped during the sprint

Define effort left on stories or tasks rolling over

Identify opportunities for velocity adjustments or ways to make planning more effective

Account for sprint rollover and other factors that may reduce capacity, including holidays, vacation time, offsites, and dev days

Optional: Set a sprint goal (avoid making it “ship x number of stories”)

Discuss which of the prioritized stories the team can commit to

Facilitate tradeoff discussions (e.g. two 3-point stories over one 5-point story)

Account for unknowns in any of the stories

Featured image source: IconScout

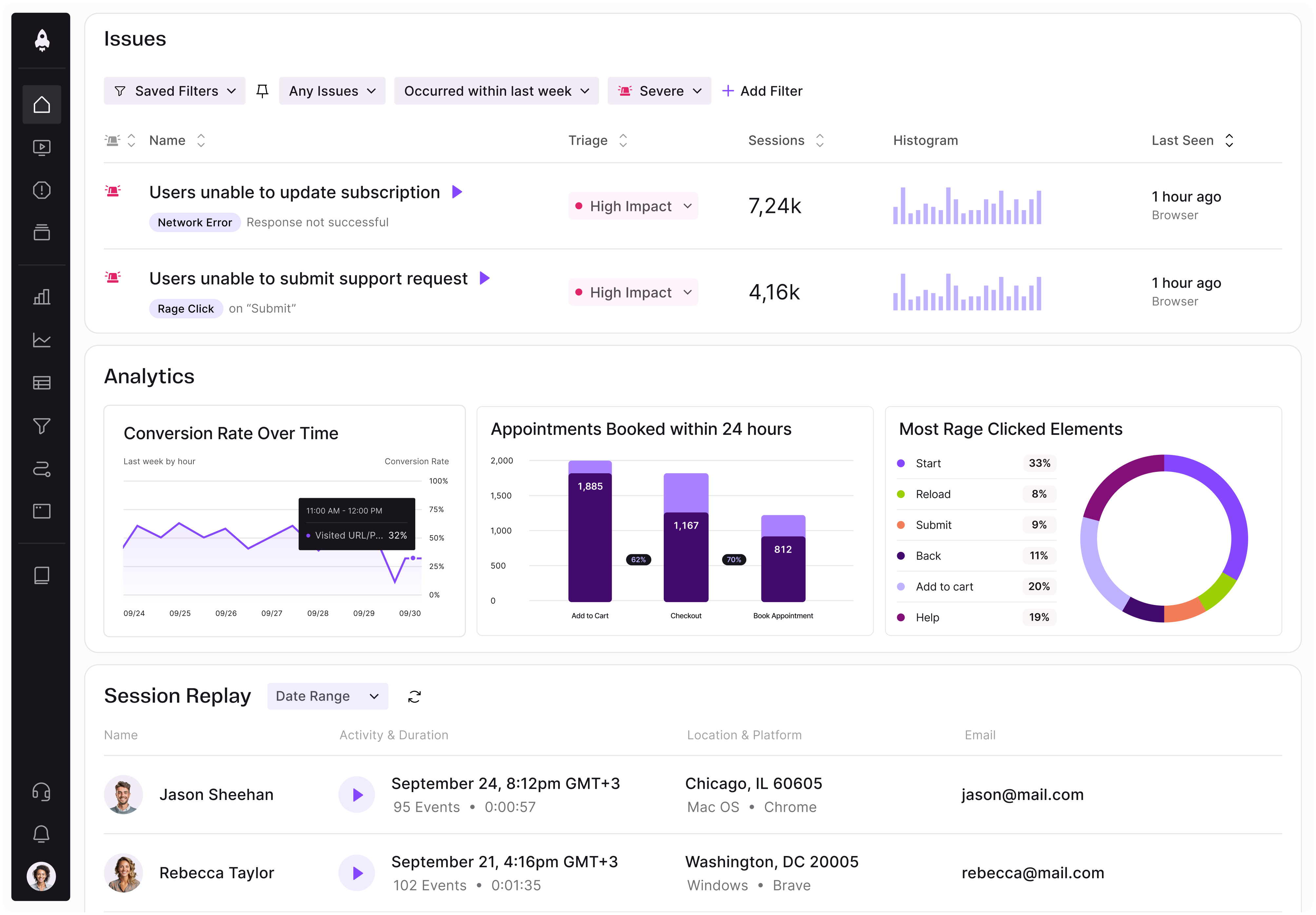

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.