The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

TypeScript provides a very rich toolbox. It includes mapped types, conditional types with control flow-based analysis, type inference, and many more.

It’s not an easy task for many JavaScript developers who are new to TypeScript to switch from loose typing to static typing. Even for developers who have been working in TypeScript for years, it can be confusing as the typing system continuously evolves.

A common myth about advanced types is that it should mainly be used for building type libraries and is not required for day-to-day TypeScript work.

The truth is that TypeScript advanced types are very useful for daily TypeScript work. They’re a great tool for building a strongly typed system into your code, expressing your intentions clearly, and making your code safer.

The purpose of introducing the type flowing concept is to think about the typing system in a way that’s similar to how we think about reactive programming data flow.

By looking at the typing system from a new perspective, it will help us to “think in types” and utilize the more advanced tools in the TypeScript toolbox in a systematic way.

In reactive programming, data flows between reactive components. In the TypeScript typing system, types can flow as well.

The first time I encountered the concept of “Type flowing” was in Basarat Ali Syed’s TypeScript book. He explains this idea in the following way:

The types flowing is just how I imagine in my brain the flow of type information.

Inspired by this, I wanted to expand the type flowing concept to the typing system level. My definition of type flowing is:

Type flowing is when one or more subtypes are mapped and transformed from a source type. These types form a strongly constrained typing system through type operations.

The basic form of type flowing can be done via type aliases.

Type aliases allow you to create a new type name for an existing type. In the example below, the type alias TargetType is assigned as a reference to the SourceType, so the type is transferred.

type SourceType = { id: string, quantity: number };

type TargetType= SourceType; // { id: string, quantity: number };

Thanks to the power of type inferences, types can flow in a few different ways. These include:

return type function, which is inferred by the return statements; e.g., the following function is inferred to return a number typedecrease function with “DecreaseType” type converts the a,b value to a number typeThe following code snippets illustrate the above cases.

const quantity: number = 4;

const stockQuantity = quantity;

type StockType= typeof stockQuantity; // number

// function return type

function increase(a: number) {

return a + 1;

}

const result = increase(2); // number

// function parameters matching

type DecreaseType = (start: number, offset: number) => number;

const decrease: DecreaseType = (a,b) => { // a: number, b: number

return a- b;

}

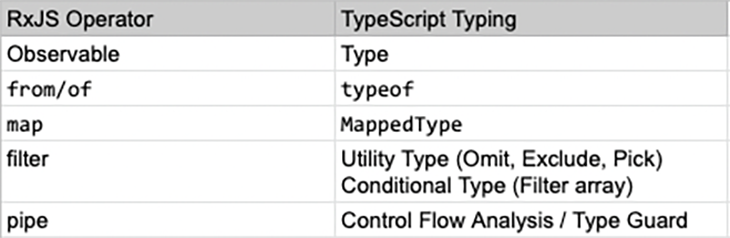

The core of reactive programming is the flowing of data between the source and the reactive components. Some of its concepts are very similar to the TypeScript typing system, as you can see in the chart below.

You can see a comparison between the RxJS operator concepts and TypeScript typing. In the typing system, the type can be transformed, filtered, and mapped to one or more subtypes.

These subtypes are “reactive” as well. When the source type changes, the subtypes will be updated automatically.

A well-designed type system will add strongly typed constraints to the data and functions in the app, so any breaking changes made to the source type definition will show an immediate compile time error.

While there are some similarities between RxJS and TypeScript typing, there are still a lot of differences between the two. For example, the data flow in RxJS occurs at runtime, while type flowing in TypeScript occurs at compile time.

The purpose of referencing RxJS here is to illustrate the flow concept in RxJS, which will hopefully help us build a shared understanding of “thinking with types.”

The two most frequently used operators in reactive programming are map and filter. How should we perform these two operations for types in TypeScript?

The mapped type is the equivalent of the map operator in RxJS. It allows us to create a type that is based on another type using the first one’s index signature and generic types.

When you combine conditional types with type inference, the type transformations you can achieve with mapped types are beyond imagination. We’ll discuss how to use mapped types later in the article.

The equivalent of arrays in type flowing is the union type. To apply filters on union types, we need to use conditional types and the never type. As filter is such a common need, TypeScript provides the exclude and extract utility types right out of the box.

The below code uses conditional types to remove types from T that are not assignable to U. The never type is used here for type narrowing, or filtering out the options of a union type.

type Exclude<T, U> = T extends U ? never : T; type T1 = Exclude<"a" | "b" | "c" , "a" >; // "b" | "c" type Extract<T, U> = T extends U ? T: never; type T2 = Extract<"a" | "b" | "c" , "a" >; // "a"

We can also filter the type properties using the out-of-the-box TypeScript utility types.

type Omit<T, K extends string | number | symbol> = {[P in Exclude<keyof T, K>]: T[P]; }

type T1 = Omit<{ a: string, b: string }, "a"> // { b: string; }

Using control flow analysis with type guard, we can pipe the flow the way the pipe operator does in RxJS.

Below is an example using type guard to perform type checks, which narrow the type to a more specific one and control the logic flow.

function doSomething(x: A | B) {

if (x instanceof A) {

// x is A

} else {

// x is B

}

}

In the above example, the TypeScript compiler analyzes all possible flows of control for the expression. It looks at the x instance of A to determine the type of x to be A within the if block, and narrows the type to B in the else block.

If we think of that as the logic branching, it can be used in a connective way, similar to the way water flows through a pipe and can be redirected to a different, connected pipe to reach its destination.

With the theory out of the way, let’s put this idea into practice. Below, we’ll look at how the type flowing concept can be put into practice by mapping, filtering, and transforming the types to implement a well-constrained typing system.

We are building a Node.js app with the mapper pattern. To implement the pattern, we must first define some mapper methods, which take data entity objects and map them to a data transfer object (DTO).

On the flip side, there is another set of methods to convert the DTOs to corresponding entity objects.

export class myMapper {

toClient(args: ClientEntity) : ClientDto { ...};

fromClient(args: ClientDto) : ClientEntity{ ...};

toOrder(args: OrderEntity) : OrderDto { ...};

fromOrder(args: OrderDto) : OrderEntity{ ...};

}

We’ll use a simplified, contrived example to demonstrate the following two goals with our strong typing system:

First, we need to define the types for the entities and DTOs.

type DataSchema = {

client: {

dto: { id: string, name: string},

entity: {clientId: string, clientName: string}

},

order: {

dto: { id: string, amount: number},

entity: {orderId: string, quantity: number}

},

}

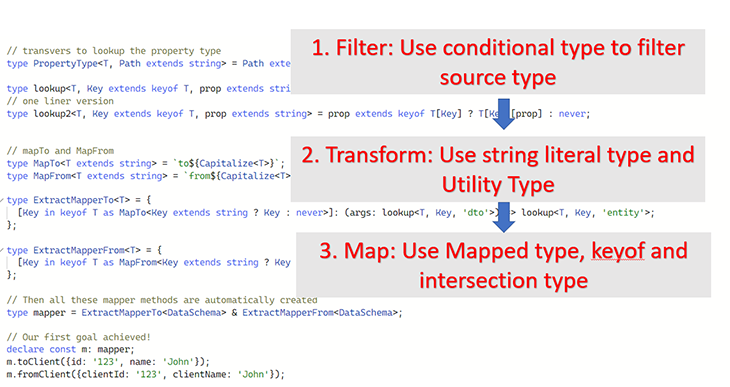

Now that we have the raw data types defined, how do we extract each entity and DTO type from them?

We’ll use conditional types and never to filter out the required data type definitions.

type PropertyType<T, Path extends string> = Path extends keyof T ? T[Path] : never; type lookup<T, Key extends keyof T, prop extends string> = PropertyType<T[Key], prop>;

We can simplify the above by merging them into a single lookup type.

type lookup<T, Key extends keyof T, prop extends string> = prop extends keyof T[Key] ? T[Key][prop] : never;

The above lookup type only works for a single-level property. What happens when the source type has more depth?

To access a property type with more depth, we’ll create a new type with recursive type aliases.

type PropertyType<T, Path extends string> =

Path extends keyof T ? T[Path] :

Path extends `${infer K}.${infer R}` ? K extends keyof T ? PropertyType<T[K], R> :

never :

never;

type lookup<T, Key, prop extends string> = Key extends keyof T? PropertyType<T[Key], prop>: never;

When Path extends keyof T is truthy, it means the full path is matched. Thus, we return the current property type.

When Path extends keyof T is falsy, we use the infer keyword to build a pattern to match the Path. If it matches, we make a recursive call to the next-level property. Otherwise, it will return a never and that means the Path does not match with the type.

If it does not match, continue recursively with the current property as the first parameter.

Now, it’s time to create the mapper methods. Here, we use string literal types to form MapTo and MapFrom with the help of the Capitalize utility type.

// MapTo and MapFrom

type MapTo<T extends string> = `to${Capitalize<T>}`;

type MapFrom<T extends string> = `from${Capitalize<T>}`;

When we assemble the previous parts, our first goal is achieved!

We make use of the key remapping feature (i.e., the as clause in the below code block), which has only been available since the release of TypeScript 4.1.

Please also note that Key extends string ? Key : never is needed because the type of object keys can vary among strings, numbers, and symbols. We are only interested in the string cases here.

type ExtractMapperTo<T> = {

[Key in keyof T as MapTo<Key extends string ? Key : never>]: (args: lookup<T, Key, 'dto'>) => lookup<T, Key, 'entity'>;

};

type ExtractMapperFrom<T> = {

[Key in keyof T as MapFrom<Key extends string ? Key : never>]:(args: lookup<T, Key, 'entity'>) => lookup<T, Key, 'dto'>;

};

// Then all these mapper methods are automatically created

type mapper = ExtractMapperTo<DataSchema> & ExtractMapperFrom<DataSchema>;

We can see below that all of the mapper method interfaces are automatically created.

// Our first goal achieved!

declare const m: mapper;

m.toClient({id: '123', name: 'John'});

m.fromClient({clientId: '123', clientName: 'John'});

m.toOrder({id: '123', amount: 3});

m.fromOrder({orderId: '345',quantity: 4});

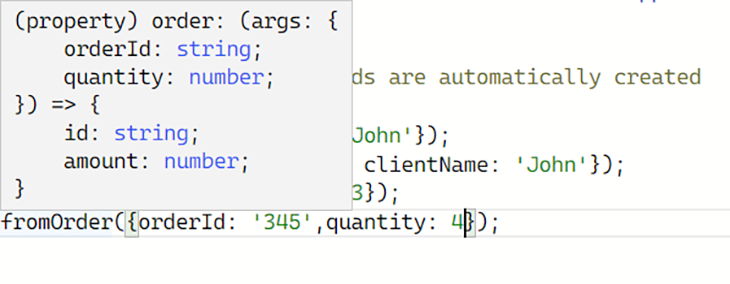

We have nice IDE IntelliSense support as well.

Our next goal is to create a union type to represent data type names from the source DataSchema type.

The key to the solution is the PropToUnion<T> type.

// Derive the data type names into a union type

type PropToUnion<T> = {[k in keyof T]: k}[keyof T];

type DataTypes = PropToUnion<DataSchema>; // 'client' | 'order'

First, {[k in keyof T]: k} extracts the key of T as both key and value using keyof. The output is:

{

client: "client";

order: "order";

}

Then, we use the index signature [keyof T] to extract the values as a union type.

The generated union type can help us enforce type safety. Let’s say we have placed the following function in another module far away from the source type. In the getProcessName function, the switch statement triggers the type guard and never is returned in the default case to tell the compiler that it should never be reached.

// Second goal achieved

function getProcessName(c: DataTypes): string {

switch(c) {

case 'client':

return 'register' + c;

case 'order':

return 'process' + c;

default:

return assertUnreachable(c);

}

}

function assertUnreachable(x: never): never {

throw new Error("something is very wrong");

}

This is how the union type and never help to enforce type safety.

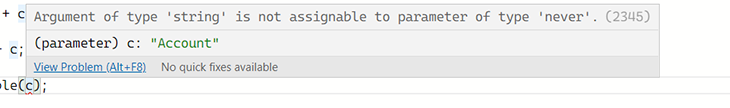

Now, let’s assume there’s been a change to the data schema — we add a new data type called account. In a large team, the developer adding the new type may not be aware of the impact of the change. Without typing constraints, it could result in a hidden runtime error that is hard to find.

If we use type flowing to build the typing constraints, the downstream subtypes will be automatically updated as below.

type DataTypes = "client" | "order" | "Account"

The TypeScript compiler will also show an error in the getProcessName function to prompt us that a breaking change has occurred.

Our second goal is achieved! We have a union type that now represents entity names and contributes to type safety.

To recap, this diagram shows the main steps we took to achieve the first goal of type flowing.

Overall, we created several new types based on the original source type. Any changes to the source type will trigger updates to all of the downstream types automatically, and we will get an instant error prompt if the change breaks the functions that depend on it.

The full example code can be found in the below Gist.

This article discusses the TypeScript type flowing concept with reference to reactive programming in RxJS. We applied the type flowing concept to a practical example by building a well-constrained type system to maximize the benefits of type safety.

I hope this discussion helps to change the idea that TypeScript’s advanced types are only for developing type libraries or for complex framework-level programming. I also hope it can help you to start applying the typing system more creatively in your daily TypeScript work.

Happy typing!

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks, and with plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you understand your web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now