ref() and reactive()Editor’s note: This article was updated by Carlos Mucuho on 30 April 2024 to explore the use of Vue 3’s onMounted Hook as well as to offer a comparison between the Composition API and the Options API. For a deeper dive into that comparison, check out this guide. Before that, it was updated to include information about using the watch() function to watch refs change and using template refs to create implicit references. For a more comprehensive overview of refs in Vue, see this guide.

In a single-page application (SPA), reactivity refers to the application’s ability to update its user interface in response to changes in the underlying data. Reactivity allows us to write cleaner code, preventing us from having to manually update the UI in response to data changes. Instead, the UI updates automatically.

However, JavaScript doesn’t work like this on its own, so we can achieve reactivity using libraries and frameworks like React, Vue, and Angular. For example, in Vue, we can create a data set called state; Vue then uses a system of observers and watchers to keep track of the state and update our UI.

When Vue detects changes in the state, it uses a virtual DOM to re-render the UI and ensure that it is always up to date, making the process as fast and efficient as possible through techniques like memoization and selective updates. There are a few different ways to define the application state that we want Vue to keep track of. For example, before the Composition API in Vue 3, we used a data function that returned the object we wanted to track.

However, with the Composition API, we use two functions for defining state: ref() and reactive(). In this article, we’ll explore these two functions, outlining what makes them unique and learning when we should use them. As a bonus, we’ll also look at how to unwrap refs, watch them change, and use them to create implicit references.

reactive()We can use reactive( ) to declare state for objects or arrays in Vue using the Composition API:

import { reactive } from 'vue'

const state = reactive({

first_name: "John",

last_name: "Doe",

})

In the code snippet above, we declare to Vue that we want to track the object in the reactive( ) function. We can then create a UI that depends on this reactive object, and Vue will keep track of the state object and use it to update the UI:

<template>

<div>{{state.first_name}} {{state.last_name}}</div>

</template>

<script>

import { reactive } from 'vue'

export default {

setup() {

const state = reactive({

first_name: "John",

last_name: "Doe",

})

return { state }

}

}

</script>

In the code above, we display the reactive data in our state. Now, Vue’s reactivity system can keep track of that data and update the UI when it changes.

We can test this by creating a function that changes the first_name and last_name when we click a button:

<template>

<div>{{state.first_name}} {{state.last_name}}</div>

<button @click="swapNames">Swap names</button>

</template>

<script>

import { reactive } from 'vue'

export default {

setup() {

const state = reactive({

first_name: "John",

last_name: "Doe",

})

const swapNames = () => {

state.first_name = "Naruto"

state.last_name = "Uzumaki"

}

return { state, swapNames }

}

}

</script>

When the button is clicked, the swapNames function changes the first_nameand last_name, and Vue updates the UI content instantly.

The reactive() function is a powerful tool for creating reactive objects in Vue components, but because it works under the hood, it has one major limitation: it can only work with objects. Therefore, we can’t use it with primitives like strings or numbers. To handle this limitation, Vue provides a second function for declaring reactive state in applications: ref().

ref()The ref() function can hold any value type, including primitives and objects. Therefore, we use it in a similar way to the reactive() function:

import { ref } from 'vue'

const age = ref(0)

The ref() function returns a special reactive object. To access the value that ref() is tracking, we access the value property of the returned object:

import { ref } from 'vue'

const age = ref(0)

if(age.value < 18) {

console.log("You are too young to drink. Get lost!")

} else {

console.log("Have some ale mate!")

}

The code below shows how we would make a UI that reacts to the changes of the age ref():

<template>

<h1>{{age}}</h1>

<button @click="increaseAge">+ Increase age</button>

<button @click="decreaseAge">- Decrease age</button>

</template>

<script>

import { ref } from 'vue'

export default {

setup() {

const age = ref(0);

const increaseAge = () => {

age.value++

}

const decreaseAge = () => {

age.value--

}

return { age, increaseAge, decreaseAge }

}

}

</script>

You may notice that we didn’t need to specify the value when using the age ref() in the template. Vue automatically applies unref() to the age when we call it in a template, so we never need to use the value in the template.

We could rewrite the example from the first reactive() property with a ref; the only difference is that we’d need to use the .value property to access the value in our JavaScript code.

ref() vs. reactive(): Which should you use?The significant difference between ref() and reactive() is that the ref()function allows us to declare reactive state for primitives and objects, while reactive() only declares reactive state for objects.

We also have to access the value of ref() by using the .value property on the returned object, but we don’t have to do that for reactive() objects.

Therefore, in real-world scenarios, you’ll find more Vue code that uses ref() than reactive(), but reactive() is perfect because it can easily accept state as it was defined before the Composition API. Both effectively track reactivity, so which one to use is a matter of preference and coding style.

Vue 3 didn’t completely eliminate the default way we defined reactive state in Vue 2; instead, Vue 3 ships with two APIs: the Composition API and the Options API. The Options API works primarily the way Vue 2 worked:

<template>

<h1>{{age}}</h1>

<button @click="increaseAge">+ Increase age</button>

<button @click="decreaseAge">- Decrease age</button>

</template>

<script>

import { ref } from 'vue'

export default {

data: function() {

return {

age: 0

}

},

methods: {

increaseAge() {

this.age++

},

decreaseAge() {

this.age--

}

}

}

</script>

In the example above, we declare age in the state and set it to zero. With methods, we can increase or decrease the age, and then see the data change on the view with each button click. The code above uses the Options API and is valid for both Vue 2 and 3.

The data property returned from Vue 2 works very similarly to the reactive()function in the Composition API we discussed earlier. It only works as an object; you can’t return a primitive value like a string from the function that the data property contains.

ref() and reactive()Migrating an application from the Vue 2 Options API to the Vue 3 Composition API is fairly straightforward. We can easily convert Vue 2 state to either ref() or reactive(). Take a look at the following Vue 2 component:

<template>

<div>

<button @click="increase">Clicked {{ xTimes }}</button>

</div>

</template>

<script>

export default {

data: function () {

return {

xTimes: 0

}

},

methods: {

increase() {

this.xTimes++

}

}

}

</script>

We can easily rewrite this component to show it using ref(). Consider the code snippet below:

<template>

<div>

<button @click="increase">Clicked {{xTimes}}</button>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import {ref} from "vue"

export default {

setup() {

const xTimes = ref(0)

return {xTimes}

},

methods: {

increase() {

this.xTimes++

}

}

}

</script>

We can also rewrite this component to show it using reactive():

<template>

<div>

<button @click="increase">Clicked {{ state.xTimes }}</button>

</div>

</template>

<script setup>

import { reactive } from "vue"

const state = reactive({

xTimes: 0

})

const increase = () => {

state.xTimes++

}

</script>

We can make this code more fluent by using the Options API, which would look more like the following code:

<template>

<div>

<button @click="increase">Clicked {{ state.xTimes }}</button>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import { reactive } from "vue"

export default {

setup() {

const state = reactive({

xTimes: 0

})

return { state }

},

methods: {

increase() {

this.state.xTimes++

}

}

}

</script>

ref() and reactive()The downside of using ref() is that it can be inconvenient to always have to use .value to access your state. If you have to use a value that could be a ref(), you might not know if it has been initialized, and calling .value on null could throw a runtime error. To get around this issue, we could unref the ref(), which we’ll discuss later in this article.

On the other hand, the downside of using reactive() is that it cannot be used on primitives. You can only use reactive() on objects and object-based types like Map and Set. You could circumvent this issue by using reactive() in the same way that state is defined in the Options API.

ref() and reactive(): Is it a good idea?There’s no rule or convention against mixing ref() and reactive(). Whether or not to do so is subjective and depends on the preferences and coding patterns of the developer(s) involved.

There are a few libraries, like Vuelidate, that use reactive() for setting up state for validations. In such cases, combining multiple ref() functions for other states and reactive() functions for validation rules could make sense.

It’s essential that you agree on a convention with your team to avoid confusion as you write code. ref() and reactive() are very efficient tools for declaring state, and they can be used together without any technical drawbacks.

ref() unwrappingVue improves the ergonomics of using ref() functions by automatically unwrapping it in certain circumstances. When using a ref() in these cases, we don’t have to use .value because Vue automatically does that for us in unwrapping.

One place where Vue unwraps ref() functions for us is in the template. When accessing a ref() from the template, we can retrieve the value of the ref()without using .value, as shown below and in the examples above:

<template>

<div>

<button @click="increase">Clicked {{xTimes}}</button>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import {ref} from "vue"

export default {

setup() {

const xTimes = ref(0)

return {xTimes}

},

methods: {

increase() {

this.xTimes++

}

}

}

</script>

When a ref() is set as a value of a reactive() object, Vue also automatically unwraps the ref() for us when we access it, as shown below:

<template>

<div>

<button @click="increase">Clicked {{ state.count }}</button>

</div>

</template>

<script setup>

import { ref, reactive } from "vue";

const state = reactive({

count: ref(0),

});

function increase() {

state.count++;

}

</script>

watch() functionWe can watch for changes to a reactive value by ref() or reactive() using the watch function. The watch function enables us to define a callback that will be triggered whenever the value of the watched reactive changes. It provides the previous and current values as parameters to the callback function, thus allowing us to perform some actions based on the changed value.

This function is particularly useful when we need to react to changes in a ref and update other parts of our application accordingly, such as triggering side effects, updating UI elements, or making API calls:

<template>

<div>

<button @click="increase">Clicked {{ count }}</button>

</div>

</template>

<script setup>

import { ref, watch } from "vue";

const count = ref(0)

watch(count, (newValue, oldValue) => {

console.log(`The state changed from ${oldValue} to ${newValue}`)

});

function increase() {

count.value += 1;

}

</script>

In the code snippet above, the reactive value is supplied as the first argument to the watch function and the callback function provides the new and old values to be acted upon.

It’s important to realize that the watch() function may not work as intended if the value of that property is not reactive(). For instance, to watch the value of count in the example defined above, the watch() function can also take a callback as its first argument, as shown in the snippet below:

<template>

<div>

<button @click="increase">Clicked {{ state.count }}</button>

</div>

</template>

<script setup>

import { ref, reactive, watch } from "vue";

const state = reactive({

count: 0,

});

function increase() {

state.count += 1;

}

watch(() => state.count, (newValue, oldValue) => {

console.log(`The state changed from ${oldValue} to ${newValue}`)

});

</script>

In Vue, refs can also be used to identify components or DOM. When a ref is used like this, it is called a template ref. Template refs are useful when we want to target the underlying DOM element of a Vue component:

<template>

<button ref="child">Click</button>

</template>

<script setup>

import { ref, onMounted } from 'vue'

const child = ref(null)

onMounted(() => {

console.log(child.value)

})

</script>

In the code snippet above, the Vue component uses a ref to target a child component defined in its template. The ref then holds the instance of the component and can be used to carry out DOM operations.

Template refs allow us to access child components or elements within a component template without assigning them a ref attribute. Template refs work by automatically creating an implicit reference to a child component or element based on its unique identifier within the template, thus simplifying the process of accessing a child component.

This is particularly useful when dealing with dynamic or nested structures. Vue assigns the reference as a property on the parent component’s instance, making it accessible within the component’s JavaScript code.

It is important to remember that implicit refs only work for direct child components or elements within a template.

onMounted with reactive statesIn Vue 3, the onMounted lifecycle Hook can be used in conjunction with reactive states to enhance reactivity and manage complex component logic. onMounted is called after the component has been mounted to the DOM, making it a suitable place to initialize data, fetch data from APIs, or perform other setup tasks.

Here’s an example demonstrating the use of onMounted with reactive states:

<template>

<div>

<h1>{{ message }}</h1>

</div>

</template>

<script setup>

import { onMounted, ref } from 'vue'

const message = ref('')

onMounted(() => {

setTimeout(() => {

message.value = 'Data loaded successfully!'

}, 2000)

})

</script>

In this example, message is a reactive state that holds the message to be displayed in the template. The onMounted Hook is used to fetch data (simulated by a setTimeout function) and update the message state once the component is mounted.

Let’s consider a scenario where we not only fetch data from an API but also update the data periodically and handle cleanup when the component is unmounted:

<template>

<div>

<h1>{{ message }}</h1>

</div>

</template>

<script setup>

import { onMounted, onBeforeUnmount, onUpdated, ref } from 'vue';

const message = ref('');

let timer;

onMounted(() => {

setTimeout(() => {

message.value = 'Data loaded successfully!';

startUpdateTimer();

}, 2000);

});

onUpdated(() => {

console.log('Component updated');

});

onBeforeUnmount(() => {

clearInterval(timer);

});

function startUpdateTimer() {

timer = setInterval(() => {

message.value = 'Data updated at ' + new Date().toLocaleTimeString();

}, 1000);

}

</script>

In this example, we’ve added an onUpdated Hook to log a message whenever the component is updated. We’ve also added an onBeforeUnmount Hook to clean up the timer before the component is unmounted, ensuring that no updates occur after the component is removed from the DOM.

The Composition API and the Options API offer ways to manage reactivity but differ in how they structure and organize code. Here’s a comparison of the two APIs and when to use one vs. the other in terms of reactivity:

Options API:

data, methods, computed, watch, etc.data and setup (using ref or reactive) options are made reactive by Vue. Computed properties and watchers are also reactiveComposition API:

ref or reactive is reactive. Computed properties and watchers are also supportedApplying reactivity can help you write more concise code. In this article, we explored how to handle reactivity in Vue using the reactive() and ref() functions. In addition, we investigated how these relate to the Vue 2 Options API as well as the Vue 3 Composition API, discussing when to use each.

I hope you enjoyed this article, and be sure to leave a comment if you have any questions. Thanks!

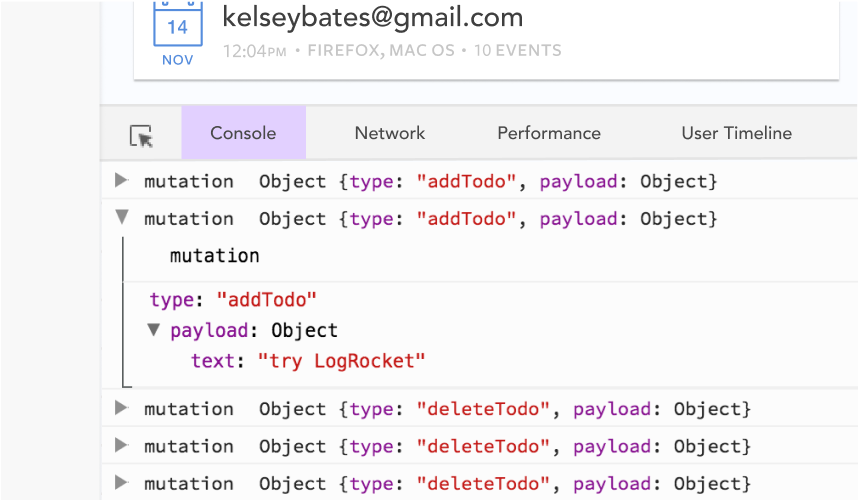

Debugging Vue.js applications can be difficult, especially when there are dozens, if not hundreds of mutations during a user session. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking Vue mutations for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket is like a DVR for web and mobile apps, recording literally everything that happens in your Vue apps, including network requests, JavaScript errors, performance problems, and much more. Instead of guessing why problems happen, you can aggregate and report on what state your application was in when an issue occurred.

The LogRocket Vuex plugin logs Vuex mutations to the LogRocket console, giving you context around what led to an error and what state the application was in when an issue occurred.

Modernize how you debug your Vue apps — start monitoring for free.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Get to know RxJS features, benefits, and more to help you understand what it is, how it works, and why you should use it.

Explore how to effectively break down a monolithic application into microservices using feature flags and Flagsmith.

Native dialog and popover elements have their own well-defined roles in modern-day frontend web development. Dialog elements are known to […]

LlamaIndex provides tools for ingesting, processing, and implementing complex query workflows that combine data access with LLM prompting.

One Reply to "Reactivity with the Vue 3 Composition API: <code>ref()</code> and <code>reactive()</code>"

Shouldn’t the example code for converting the vue 2 code to ref() and increasing the counter be as follows:

`this.xTimes.value++`, and not just `this.xTimes++`