Editor’s note: This post was last updated on 12 July 2023 to further elaborate on the differences in when and how the useEffect and useLayoutEffect Hooks are fired.

Assuming you understand the difference between useEffect and useLayoutEffect, would you be able to explain them in simple terms? Or can you describe their nuances with practical examples?

In this tutorial, we’ll explore the differences between React’s useEffect and useLayoutEffect Hooks, such as how they handle heavy computations and inconsistent visual changes, with code examples that will reinforce your understanding of the concepts.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

useEffect Hook?The useEffect Hook is a powerful tool in React that helps developers manage side effects in functional components. It runs asynchronously after the browser repaints the screen.

This hook is commonly used for handling side effects such as fetching data, working with subscriptions, or interacting with the DOM. Essentially, useEffect lets you control what happens in your component based on different situations, making your code more flexible and efficient.

useLayoutEffect Hook?The useLayoutEffect Hook is a variation of the useEffect Hook that runs synchronously before the browser repaints the screen. It was designed to handle side effects that require immediate DOM layout updates.

useLayoutEffect ensures that any changes made within the hook are applied synchronously before the browser repaints the screen. While this might not seem ideal, it is highly encouraged in specific use cases, such as when measuring DOM elements, or animating or transitioning elements.

For example, a DOM mutation that must be visible to the user should be fired synchronously before the next paint, preventing the user from receiving a visual inconsistency. We’ll see an example of this later in the article.

useEffect and useLayoutEffect?Sprinkled all over the two previous sections are pointers to the differences between useEffect and useLayoutEffect. Perhaps the most prominent of these is that the useLayoutEffect Hook is a variation of the useEffect Hook that runs synchronously before the browser repaints the screen.

Because the useLayoutEffect is a variation of the useEffect Hook, the signatures for both are exactly the same:

useEffect(() => {

// do something

}, [dependencies])

useLayoutEffect(() => {

// do something

}, [dependencies])

If you were to go through a codebase and replace every useEffect call with useLayoutEffect, it would work in most cases. For example, I’ve taken an example from the React Hooks Cheatsheet that fetches data from a remote server and changes the implementation to use useLayoutEffect over useEffect:

In our example, the code will still work. Now, we’ve established an important fact: useEffect and useLayoutEffect have the same signature. This trait makes it easy to assume that these two Hooks behave in the same way.

However, the second part of the aforementioned quote above feels a little fuzzier to most people. It states that useLayoutEffect runs synchronously before the browser repaints the screen. Essentially, the differences between useEffect and useLayoutEffect lie in when the two are fired and how they run.

Let’s consider the following contrived counter application:

function Counter(){

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

useEffect(() => {

// perform side effect

sendCountToServer(count)

}, [count])

return (

<div>

<h1> {`The current count is ${count}`} </h1>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count => count + 1)}>

Update Count

</button>

</div>

);

}

// render Counter

<Counter />

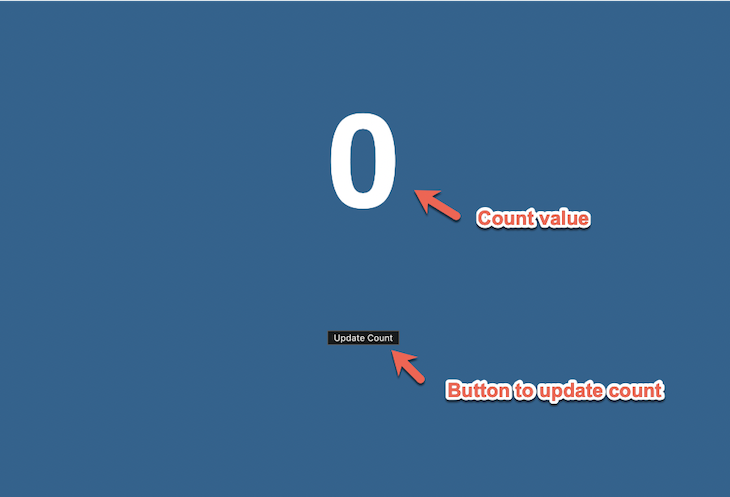

When the component is mounted, the following code is painted to the user’s browser:

With every click of the button, the counter state is updated, the DOM mutation is printed to the screen, and the effect function is triggered. Here’s what’s really happening:

count state variable internallyuseEffect function is fired only after the browser has painted the DOM change(s)With the click comes a state update, which in turn triggers a DOM mutation. The text contents of the h1 element have to be changed from the previous count value to the new value.

Steps 1, 2, and 3 do not show any visual changes to the user. The user will only see a change after the browser has painted the changes or mutations to the DOM. React hands over the details about the DOM mutation to the browser engine, which figures out the entire process of painting the change to the screen.

The function passed to useEffect will be fired only after the DOM changes are painted on the screen. The official docs put it this way:

“Even if your Effect was caused by an interaction (like a click), the browser may repaint the screen before processing the state updates inside your Effect.”

Another important thing to remember is that the useEffect function is fired asynchronously to not block the browser paint process.

N.B., although

useEffectis deferred until after the browser has painted, it’s guaranteed to fire before any new renders. React will always flush a previous render’s effects before starting a new update.

Now, how does this differ from the useLayoutEffect Hook? Unlike useEffect, the function passed to the useLayoutEffect Hook is fired synchronously after all DOM mutations.

If you replaced the useEffect Hook with useLayoutEffect, the following would happen:

count state variable internallyuseLayoutEffect function is fireduseLayoutEffect to finish, and only then does it paint this DOM change to the browser’s screenThe useLayoutEffect Hook doesn’t wait for the browser to paint the DOM changes. It triggers the function right after the DOM mutations are computed. Also, keep in mind that updates scheduled inside useLayoutEffect will be flushed synchronously and will block the browser paint process.

useEffect and useLayoutEffectThe main differences between useEffect and useLayoutEffect lie in when they are fired and how they run, but regardless, it’s hard to tangibly quantify this difference without looking at concrete examples. In this section, I’ll highlight three examples that amplify the significance of the differences between useEffect and useLayoutEffect.

Modern browsers are very fast. We’ll employ some creativity to see how the time of execution differs between useEffect and useLayoutEffect. In the first example, we’ll consider a counter similar to the one we looked at earlier:

In this counter, we have the addition of two useEffect calls:

useEffect(() => {

console.log("USE EFFECT FUNCTION TRIGGERED");

});

useEffect(() => {

console.log("USE SECOND EFFECT FUNCTION TRIGGERED");

});

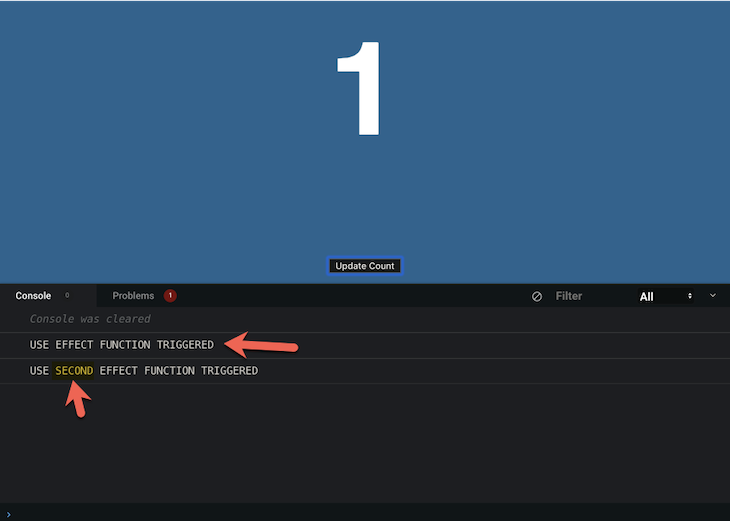

Note that the effects log different texts depending on which is triggered, and as expected, the first effect function is triggered before the second:

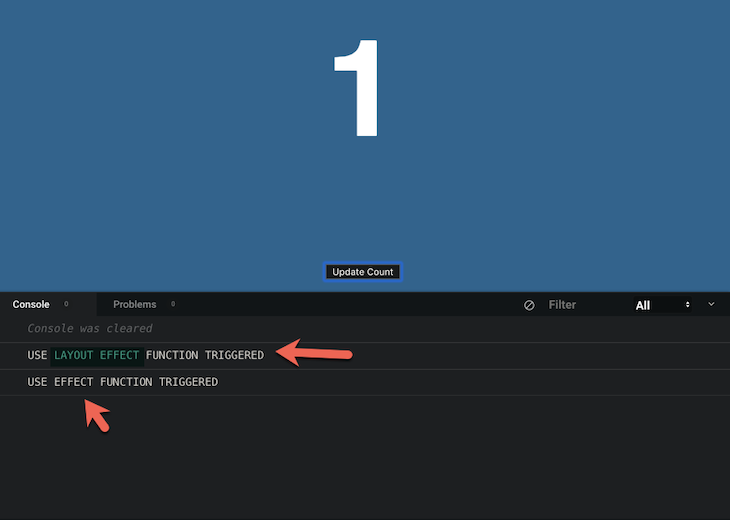

When there is more than one useEffect call within a component, the order of the effect calls is maintained. The first is triggered, then the second, and the sequence continues. Now, what happens if the second useEffect Hook is replaced with a useLayoutEffect Hook? Let’s take a look:

useEffect(() => {

console.log("USE EFFECT FUNCTION TRIGGERED");

});

useLayoutEffect(() => {

console.log("USE LAYOUT EFFECT FUNCTION TRIGGERED");

});

Even though the useLayoutEffect Hook is placed after the useEffect Hook, the useLayoutEffect Hook is triggered first! This is what it looks like:

The useLayoutEffect function is triggered synchronously before the DOM mutations are painted. However, the useEffect function is called after the DOM mutations are painted.

In the next example, we’ll look at plotting graphs with respect to the time of execution for both the useEffect and useLayoutEffect Hooks. The example app has a button that toggles the visual state of a title, whether shaking or not. Here’s the app in action:

I chose this example to make sure the browser actually has some changes to paint when the button is clicked, hence the animation. The visual state of the title is toggled within a useEffect function call. If it interests you, you can view the implementation.

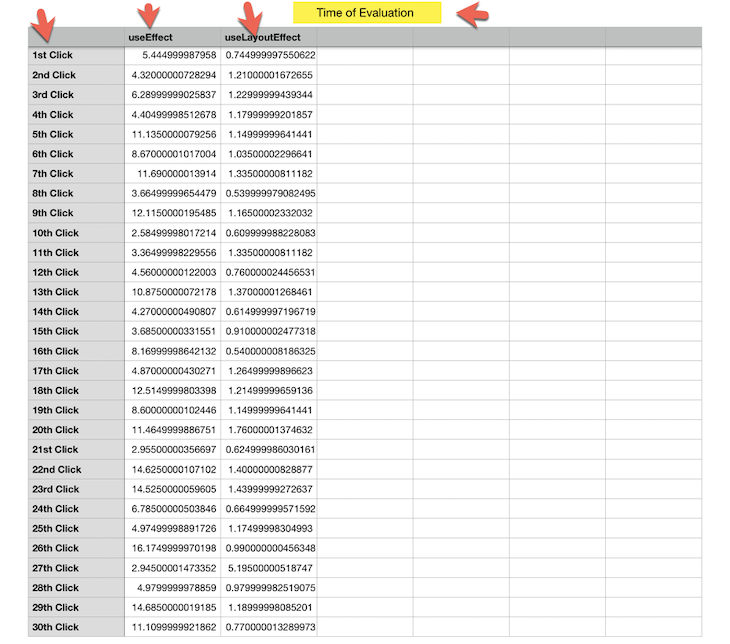

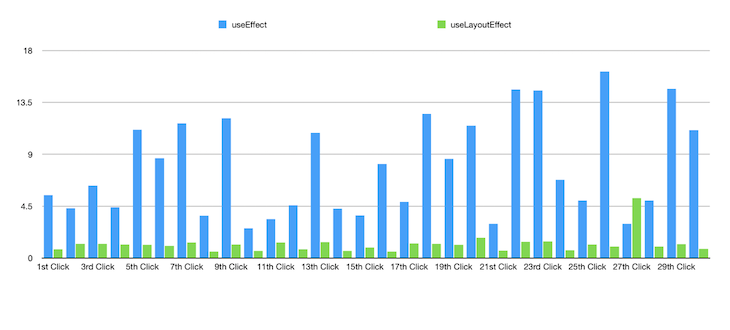

I gathered significant data by toggling the visual state every second, meaning I clicked the button using both the useEffect and useLayoutEffect Hooks. Then, using performance.now, I measured the difference between when the button was clicked and when the effect function was triggered for both useEffect and useLayoutEffect. I gathered the following data:

From this data, I created a chart to visually represent the time of execution for useEffect and useLayoutEffect:

Essentially, the graph above represents the time difference between when the useEffect and useLayoutEffect functions are triggered, which in some cases is of a magnitude greater than 10x. See how much later useEffect is fired when compared to useLayoutEffect?

You’ll see how this time difference plays a huge role in use cases like animating the DOM, which I will explain below.

Expensive calculations are, well, expensive. If handled poorly, they can negatively impact the performance of your application. With applications that run in the browser, you have to be careful not to block the user from seeing visual updates just because you’re running a heavy computation in the background.

The behavior of both useEffect and useLayoutEffect differ in how heavy computations are handled. As stated earlier, useEffect will defer the execution of the effect function until after the DOM mutations are painted, making it the obvious choice out of the two.

As an aside, I know

useMemois great for memoizing heavy computations. This article neglects that fact, instead comparinguseEffectanduseLayoutEffect. Check out this guide to theuseMemoHook if you would like more information.

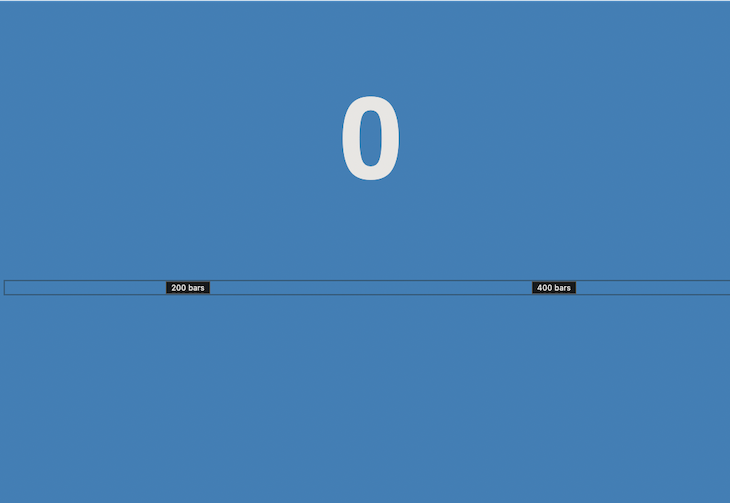

As an example, I’ve set up an app that’s not practical, but decent enough to work for our use case. The app renders with an initial screen that seems harmless:

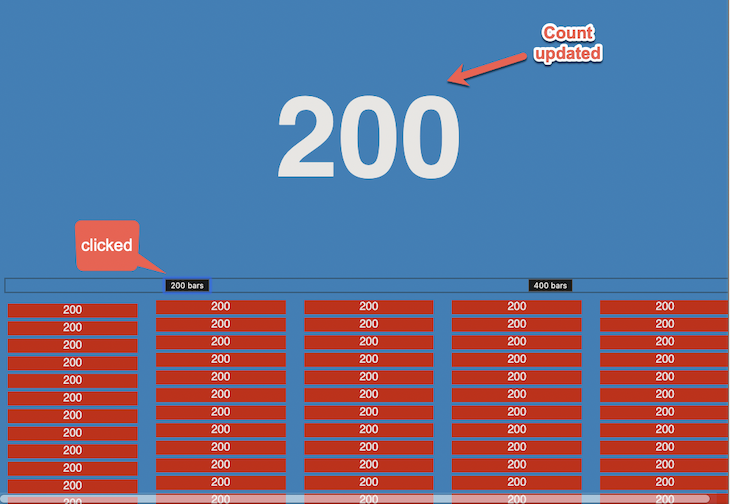

However, it has two clickable buttons that trigger some interesting changes. For example, clicking the 200 bars button sets the count state to 200:

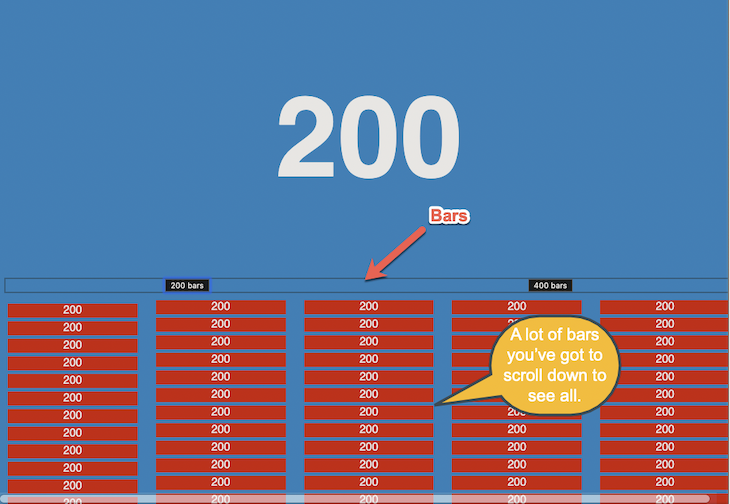

It also forces the browser to paint 200 new bars to the screen:

This is not a very performant way to render 200 bars, as I’m creating new arrays every single time. But the point of our example is to make the browser work:

...

return (

...

<section

style={{

display: "column",

columnCount: "5",

marginTop: "10px" }}>

{new Array(count).fill(count).map(c => (

<div style={{

height: "20px",

background: "red",

margin: "5px"

}}> {c}

</div> ))}

</section>

)

The click also triggers a heavy computation:

...

useEffect(() => {

// do nothing when count is zero

if (!count) {

return;

}

// perform computation when count is updated.

console.log("=== EFFECT STARTED === ");

new Array(count).fill(1).forEach(val => console.log(val));

console.log(`=== EFFECT COMPLETED === ${count}`);

}, [count]);

Within the UseEffect function, I create a new array with a length totaling the count number, in this case, an array of 200 values. I loop over the array and print something to the console for each value in the array.

We’ll still need to pay attention to the screen update and our log consoles to see how this behaves. For useEffect, our screen is updated with the new count value before the logs are triggered:

Here’s the same screencast in slow motion. There’s no way you’ll miss the screen update happening before the heavy computation! So, is this behavior the same with useLayoutEffect? No! Far from it.

With useLayoutEffect, the computation will be triggered before the browser has painted the update. The computation takes time, which eats into the browser’s paint time. Check out the same action from above replaced with useLayoutEffect:

Again, you can watch it in slow motion. You can see how useLayoutEffect stops the browser from painting the DOM changes for a bit. You can play around with the demo, but be careful not to crash your browser.

Why does this difference in how heavy computations are handled matter? When possible, you should choose the useEffect Hook for cases where you want to be unobtrusive in the dealings of the browser paint process. In the real world, this is most of the time, except for when you’re reading layout from the DOM or doing something DOM-related that needs to be painted ASAP. In the next section, we’ll see an example in action.

useLayoutEffect truly shines when handling inconsistent visual changes. As an example, let’s consider these real scenarios I encountered myself while working on my Udemy video course on Advanced Patterns with React Hooks.

With useEffect, you get a flicker before the DOM changes are painted, which was related to how refs are passed on to custom Hooks. Initially, these refs start off as null before actually being set when the attached DOM node is rendered:

With useLayoutEffect:

If you rely on these refs to perform an animation as soon as the component mounts, then you’ll find an unpleasant flickering of browser paints happening before your animation kicks in. This is the case with useEffect, but not useLayoutEffect.

Even without this flicker, sometimes you may find useLayoutEffect produces animations that look buttery, cleaner, and faster than useEffect. Be sure to test both Hooks when working with complex user interface animations.

useEffect and when to use useLayoutEffectMost of the time, the useEffect Hook should be your first choice because it runs asynchronously and doesn’t block the browser painting process, which can slow down your application. However, when you are completely sure that the code that you wish to use will visually affect your application, such as when using animations, transitions, or when you see some visual inconsistencies, use the useLayoutEffect Hook instead.

In this article, we reviewed the useEffect and useLayoutEffect Hooks in React, looking into the inner workings and best use cases for each. We also demonstrated examples of both hooks regarding their firing, performance, and visual changes.

I hope you found this guide helpful!

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Discover five practical ways to scale knowledge sharing across engineering teams and reduce onboarding time, bottlenecks, and lost context.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 4th issue.

Paige, Jack, Paul, and Noel dig into the biggest shifts reshaping web development right now, from OpenClaw’s foundation move to AI-powered browsers and the growing mental load of agent-driven workflows.

Check out alternatives to the Headless UI library to find unstyled components to optimize your website’s performance without compromising your design.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

6 Replies to "React useLayoutEffect vs. useEffect Hooks with examples"

OK, IMHO, this whole article was kinda of overkill. But, kudos for the author anyway.

TL;DR;

“`

useLayoutEffect: If you need to mutate the DOM and/or DO need to perform measurements

useEffect: If you don’t need to interact with the DOM at all or your DOM changes are unobservable (seriously, most of the time you should use this).

“`

by: Kent C. Dodd (https://kentcdodds.com/blog/useeffect-vs-uselayouteffect)

Simple and Clear !!

that was supper helpful thx 🙂

This was a super helpful article. I liked the way author was showing with live examples the differences between useEffect and useLayoutEffect hooks. Now I finally got it. Awesome!

Utilising live recordings and different examples is quite helpful for grasping the concept to the core. Thanks for the article.

Thank you so much for this! I was searching for something does the work of useLayoutEffect() to prevent the dimming of loading animation while execution of multiple useEffects.

In my code, my first useEffect calls an Api and that data was using in next api written in next useEffect, also first useEffect was printing on the browser after that fetches the data of first API. Then only it was calling the other useEffect(). That was making the dim on loading. By using useLayoutEffect () the job is done asynchronously.

Very helpful🙂