If you’re working in the world of software development, then you’ve almost certainly heard of a product roadmap — the document that helps communicate the direction and progress of the product to internal teams and external stakeholders.

A product roadmap shows what high-level features will be delivered and roughly in what order and timeframe. It also facilitates communication with different groups about what is likely to happen and when without giving too much detail on how it’s being done.

This vision supports the organization in developing a product. Just as importantly, it ensures that all parties are aware of the product direction so they can adjust activities based on this summary of features.

However, although you might have seen a product roadmap, not every organization has a business roadmap. What is this document, what does it include, and how do you know if you even need a business roadmap?

As with a product roadmap, a business roadmap is designed to facilitate communication to various stakeholder groups on the direction of the business and plan of action to achieve business goals.

The business roadmap is a high-level visualization of objectives the organization hopes to achieve and in what order. It’s effectively a representation of the proverbial big picture.

A business roadmap should give the organization and everyone in it a general outline of short- to medium-term business goals. This allows relevant stakeholders to make appropriate business decisions that support the delivery of items in the roadmap.

I know what you’re thinking: isn’t a business roadmap just a business plan? The short answer is no.

The fundamental difference between a business plan and a business roadmap boils down to the granularity of detail. A business roadmap is a much higher-level overview than a business plan, which is more precise and thorough.

For example:

This variation in depth means that anyone looking at a business roadmap will know what the outcomes are going to be but not specifically how the business intends to get there. Someone reading a business plan should understand the individual steps the business plans to take along the journey.

Here’s an example of what a business plan looks like:

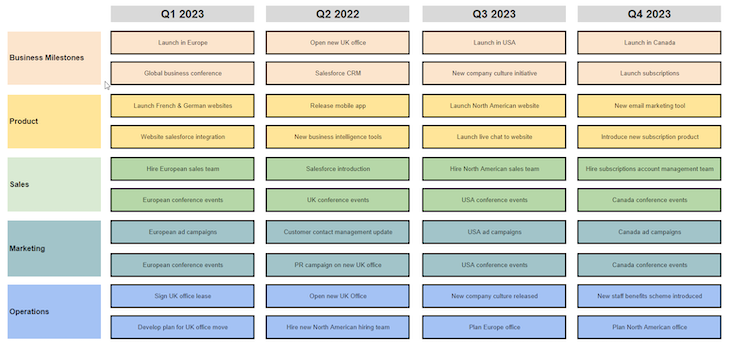

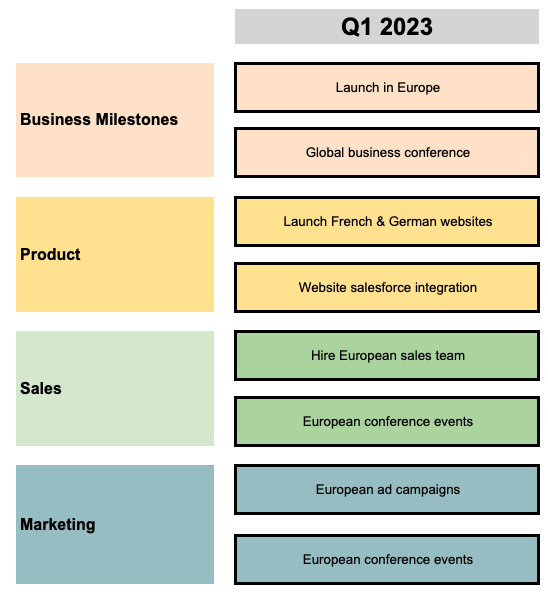

An example of a business roadmap

When you dive deeper into a business plan, you’ll also see that it covers aspects such as market analysis, sales and marketing plans, equipment requirements, and detailed financials. This provides a full, detailed view of how the business plans to operate over the short-to-medium term, which you can’t get from a business roadmap.

It’s more “We’ll have moved into a new office” rather than “We’ll be paying X for rent, and Y for new office equipment, and Z for the redirection of the post…”

When creating a business roadmap, it’s important to consider that, despite the relatively high level at which they present future activities, they do take a considerable amount of effort to produce.

As with any roadmap, there’s a need to understand inputs and priorities from across the organization and bring these together into one coherent vision. This means taking the following steps:

Start at the beginning: what are you looking to achieve?

Your objectives should be self-contained, achievable goals that are clear for everyone across the organization to understand.

In the example business roadmap described above, the first line of the roadmap looks at the high-level primary objectives for the business — e.g., launching the business in new markets (Europe, the United States, and Canada) and moving the UK office.

From these objectives, the various functions across the business can determine their own individual milestones along the journey toward success.

Once you’ve established your objectives, the next step is to determine what is already in place to help you achieve them.

Ask yourself questions such as:

The other side of business capabilities is business limitations:

The final area to consider is what activities need to occur to achieve your objectives. For example:

Once this process is completed, activities designed to drive the business toward its objectives commence. It becomes necessary to group these tasks into some form of sequential order. That’s where the business roadmap comes in.

Let’s look at an example. If, in Q2, we’re planning to achieve X, which of our activities across our different business areas need to happen in Q1 and Q2 to reach that point? These are the building blocks of our business roadmap.

Each block represents an achievable milestone for that business area, clearly defining what they are looking to achieve at that point in time.

If you’re new to business roadmaps, you’re bound to stumble here and there the first time you try to create one. It takes practice.

However, some common mistakes businesses make include:

Without a clear, overarching business vision, it’s impossible to dive down into the various business areas and set departmental milestones. An unclear objective leads to a muddying of activities and a lack of focus when moving forward.

It’s tempting to think you can get through huge amounts of work when looking at the long time periods considered in a business roadmap. However, because business goals are usually quite large in scale, the number of activities you can realistically achieve is relatively small.

Too many goals leads to frustration because your team will never be able to deliver on what they set out to achieve.

Unrealistic timelines make the invalid assumption that you can get through more activities than you think we can.

A roadmap is a high-level visualization of your milestones, but a roadmap entry is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the work required to deliver on those goals. Sometimes big things take time.

What’s the point of creating a roadmap if everyone isn’t onboard with it? There’s no value in creating a beautiful-looking roadmap if, as soon as you get into month one, someone holds up their hand and asks, “Why aren’t we doing X?”

If we look at our example business roadmap as described above, one of the business objectives in Q3 is to launch our service in the US. This primary goal for the business will drive the business roadmap entries for our various business areas.

Sales needs to understand what our capabilities currently are in the US and what might restrict us from achieving this objective. Then, it must develop some departmental goals that help the business move toward its overall objectives. This will leave us with some roadmap entries such as:

Finance needs to understand the company formation and financial reporting rules within the US, as well as how the launch will be funded, which will lead to roadmap entries such as:

Operations need to determine what we need to complete to support US recruitment and obtain an office, equipment, materials, etc. Roadmap entries directed at the operations team might include things like:

To access a full version of the business roadmap example described above, follow this link. If you’d like to use it as a template when creating your own business roadmap, click the link to download the file and, from the menu at the top of the spreadsheet, select File > Make a copy.

Although there is a considerable amount of effort that goes into creating a business roadmap, this document is essential in supporting the successful operation of a business.

The vision provided by a well-written roadmap gives focus and support to the entire organization and ensures that all areas of the business are driving toward the same destination.

At the end of the day, that’s what we want: a route to success.

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Great product managers spot change early. Discover how to pivot your product strategy before it’s too late.

Thach Nguyen, Senior Director of Product Management — STEPS at Stewart Title, emphasizes candid moments and human error in the age of AI.

Guard your focus, not just your time. Learn tactics to protect attention, cut noise, and do deep work that actually moves the roadmap.

Rumana Hafesjee talks about the evolving role of the product executive in today’s “great hesitation,” explores reinventing yourself as a leader, the benefits of fractional leadership, and more.