Dan Lawyer is Chief Product Officer at Lucid Software. He got his kickstart into product while working for Novell, which was acquired by Micro Focus. Dan then became Director of Product Management at FamilySearch, a non-profit that helps people discover their heritage and connect with family members, before joining Adobe. Most recently, he served in various product leadership roles at Ancestry and Vivint Smart Home before transitioning to his role at Lucid.

We sat down with Dan to talk about his approach to increasing the autonomy of product teams, including his philosophy that without autonomy, there is no leverage as a leader. He shares his tactics to foster a safe environment on his product teams, such as an icebreaker activity where team members place themselves on a graph to visualize how they’re feeling. Dan also discusses “vacuum theory” — an approach to showing ownership and standing out by filling a vacuum within a team.

We’re focused on our mission of helping teams see and build the future via our products: Lucidchart, Lucidspark, and Lucidscale. We think of all types of teams utilizing our product suite, such as engineering, HR teams, etc. Lucid is broadly adopted in that all knowledge workers benefit from our products. We see and build the future as a journey from idea to reality. Our products span that journey and the phases teams go through to provide specific support in visualizing together.

I’ve thought about this problem for decades as a product leader. I borrowed a process that I’ve continued to evolve into what I call product fundamentals. I try to create a repeatable process for people to figure out what product strategy is and how to turn that into executable plans. It’s meant to consolidate all the signals we need to understand strategy and then move toward product roadmapping.

I built a Lucidchart diagram to visualize this showing the workflow, phases, and people involved. The first step is gathering context. We need the information from the higher-level company, as well as business performance, market intelligence, and product performance. From there, we identify the strategic plays and outcomes. What are the signals we’re getting from the company overall, the specific plays that we need to address that signal, and the outcomes we expect?

From there, we prioritize. We think broadly, then narrow down to a specific set of plays. To run those plays, there’s a set of implied capabilities — certain things that have to exist to succeed. We identify those and then look at the outcomes and metrics that those implied capabilities need to exist to be solid-core.

The final phase of this is thematic roadmaps. What are the high-level roadmaps? There’s a slightly modified version of this for the individual product view or team level, but I like to have a carved-out process to go through these different phases. Each phase has specific deliverables and cross-functional teams coming together to analyze and provide feedback. By the time we have these thematic roadmaps, we have something tangible that our team can execute against.

Autonomy is very important to me and my teams. If I don’t create autonomy, I have no leverage as a leader and may as well not have anybody else on the team. I also respect the idea that the team, in aggregate, is much smarter than I will ever be on my own.

As I’ve become more senior in my career, it’s a problem I’ve thought about more. For example, as a chief product officer, if I go into a conversation with an individual product manager and I express my opinion, even if it’s not my intent, they can feel a loss of autonomy.

To combat that, I try to be really clear in my communication with people. Usually, when I start a relationship with a team or an individual, I tell them to assume that anything I say, unless I’m explicit that it’s a directive, is just another opinion equal to any other opinion in the room. When I interject my thoughts into a conversation, I’ll also say, “I don’t want you to over-rotate on this thought,” and that they should validate my thoughts with customers.

I also like OKRs because they create autonomy if they’re done correctly. If we do it right, the agreement is on a result, not how we get it. I tell teams they have complete latitude in getting that result.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Lucid was toying with introducing a virtual whiteboard product. It had been on the radar for a while, but when COVID hit, we knew we needed it. That’s when we conceived Lucidspark and built and released the product in less than six months, which was phenomenal. The only way we were able to do that was by providing high autonomy to teams to go fast and make decisions.

It’s funny — we have an internal “Leading at Lucid” course that people go through and graduate from. One of the tracks is all about motivation and inspiration, and I’ve been teaching that track with another executive for four years now.

I subscribe to the thinking presented in the book Drive by Dan Pink. He provided a lot of great research against his philosophies. He talks about intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation and how extrinsic motivation really isn’t a thing. The basic mindset is to get rid of the table stakes — the obvious things like paying people well enough that they don’t have to worry about supporting their families. He says that what motivates people is the pursuit of mastery, autonomy, and purpose, and people respond to those in different ways.

It’s important that when you work with a team or with an individual, you understand how each of those components is wired to them. Are they more motivated by mastery, autonomy, or purpose? It could be equal across all three, or one could not apply. Understand that and have intentional conversations with people to learn how they’re motivated.

Most people have higher-level purposes than money. At Lucid, we help people connect to the end value that our customers can create through our products. For example, one of our customers is a major global logistics provider. During the pandemic, they used our product to design all of the flows of their logistics operations to enable the broad distribution of vaccines worldwide. It was so meaningful to us. We didn’t distribute the vaccines, but we were part of the ecosystem making it happen.

It’s hard. It feels like I switch contexts every 15 minutes. Especially if I have to produce something myself, that’s tough. I have strategies for any person, either as a leader or an IC, to manage this effectively. I pre-block chunks of time in my calendar that are reserved just for me. It’s easier for me as a senior leader because my schedule tends to be harder to coordinate than others.

I believe in time boxing — carving out chunks of time and honoring them. I also establish strong boundaries of how long I’m willing to work. For example, when my kids were younger, I told my wife, “My commitment to you is I will never stay at the office past 5:30. I’ll come home, and once the kids are in bed, if I need to do a little more work, I’ll do it then.” It wasn’t my intent, but that forced me to be much more rigorous in prioritizing what I do in a day because I couldn’t solve problems by adding more time to what I did.

I got much smarter about what did and didn’t create value and got smarter about saying no to things. As a product manager, there is a never-ending list of steps you could do. I’ve become a master at prioritizing what’ll create value. I’m the best at ignoring things.

Often, a leader’s mental model can look like spending money on a credit card. If you give them a credit card with no limit and they have no idea how much anything costs, they’ll just pull up the card and swipe it.” If you hold them accountable for their spending and set a limit, they’ll behave differently.

This can be applied to prioritization and the tasks you’re giving someone. It’s unhealthy to have an environment where the leader just acts like they have a credit card without a limit and never pay a bill. Thinking about it this way helps me when somebody on my team says, “These are all of the things that I’m working on, and these are the things that I’ve prioritized. Let’s talk about it together. I’m willing to prioritize it the way you think it should be prioritized.” The leader needs to set a limit to how much that person can realistically accomplish.

They always show up with a huge list, and there are many items on there that I advise them to not worry about. There are also always some items that are higher priority than the person thought, so we size that and get aligned. But, I know there’s a limit to how much this person can do. We draw that line together. Those conversations are super healthy and helpful, and there needs to be that feedback mechanism.

The thing that has been most effective for me is publicly acknowledging my shortcomings and mistakes. At times, I even ask the team to forgive me for them. It signals that it’s OK to make mistakes and acknowledge them. That makes it safe for people to say, “I messed up.” In reality, they didn’t mess up, they’re usually just unhappy with their performance.

I also like to find opportunities to signal that I care about my team as people first and as employees second. In my leadership meetings, we start with an icebreaker that has nothing to do with work and has everything to do with us as people. Sometimes, they’re fun and playful. Other times, I’ll run an activity where people drag their faces virtually to a quadrant around how they’re feeling. The axes are mental state and workload.

There’s a difference between being overwhelmed but in a good state of mind and being overwhelmed in a bad state of mind. I call the upper left-hand quadrant, which is high workload and low wellness, “intervention needed.” It’s transparent, but often, the resolution is to step in and help.

I like to give back to people. I’m very motivated by the thought of helping people master product faster than I did. One of the questions I often get is, “How do I become distinguished and get a level ahead in my career?” I did a presentation years ago at Brigham Young University — they wanted me to talk about how to be a rock star in your first product gig. That’s where I first termed the phrase “vacuum theory,” because in any company, regardless of its size, there will be vacuums.

There will be things that nobody is doing or has the bandwidth to do, but that everybody would be grateful for if they were done. One of the ways to show ownership and to stand out is to fill a vacuum. Part of the vacuum theory is that it’s rare that you need to ask permission to do so as long as you don’t drop the ball on your day job or miss any commitments. If you can fill a vacuum, people are going to be thrilled.

When I started in software, I worked for a company called WordPerfect. It was the market leader ahead of Microsoft Word in word processing. The philosophy was that you got some media with software in it, and a huge book came with it that told you how to use the software. My role was a typesetter, so I created those books internationally. I was typesetting in foreign languages, which meant constantly interacting with translators overseas.

We had a process of sending the typeset files to the translators, and the translators would look at them, edit them, make sure everything was good, and send them back. There was a lot of back and forth and they were mailing these manuscripts to each other and with physical markups. I looked at that and thought there had to be a more efficient way. Email was just starting to be a thing back then.

I created a whole system that allowed us to use macros and keystrokes to mark up the files with all the things that the translators would do, but digitally. They could do everything that they were doing physically on the printed paper. We would put the files on a shared drive and notify them through email. It reduced the turnaround time on these manuscripts from weeks to hours. The effort level was greatly reduced. Nobody asked me to do that. I had just realized how much time and resources we were wasting on the process and figured out how to automate and digitize it.

Dee Hock, the founder of Visa, came up with this. I came upon an article that talked about his philosophy for hiring when I was doing research to write my first job description. It’s stuck with me since then.

There’s a relationship between integrity, motivation, and capacity. They’re all important, but the sequencing of them is more important. Motivation without integrity is dangerous. And it doesn’t matter how motivated you are if you don’t have the capacity to succeed. On the other hand, knowledge and experience can be obtained. We can spend time with you. There’s intentional sequencing there, and I’ve found it to be true.

I take this a step further, which is hiring people and thinking about trajectories. I think of it like I’m plotting them on a graph. Here’s where they are today, here’s where they were 12 months ago, and here’s where I think they will be 18 months from now. That presumes that they have integrity and motivation. Then, I think about where they’re going to be in terms of capability, knowledge, and experience on that time horizon.

I would rather hire someone on a sharp trajectory because they make things happen. The most exciting things happen around people on fast trajectories.

Lucid is a collaboration company, so we think a lot about this. All of our products are designed for both synchronous and asynchronous collaboration. I heard a phrase once years ago that said it takes four to eight to innovate, and I believe that to foster the most meaningful collaborations, the sweet spot is truly four to eight people. If you get higher than that, you’re probably not collaborating — you’re just sharing information.

Aside from the size of the group, the other question is what’s your medium? What’s your format? Where are you doing this collaboration? Historically, in a product role, product managers would physically get in the same room and put paper on the walls. You could never find a big enough wall to get all your thinking out. Today, a lot of that happens on virtual whiteboards, like Lucidspark. It’s purpose-built for both real-time and async collaboration.

I also believe in creativity and fun. It’s hard for me to collaborate if there isn’t an element of play and fun ingrained within it. Icebreakers can help with that, but I will spontaneously interject that at any point that I can.

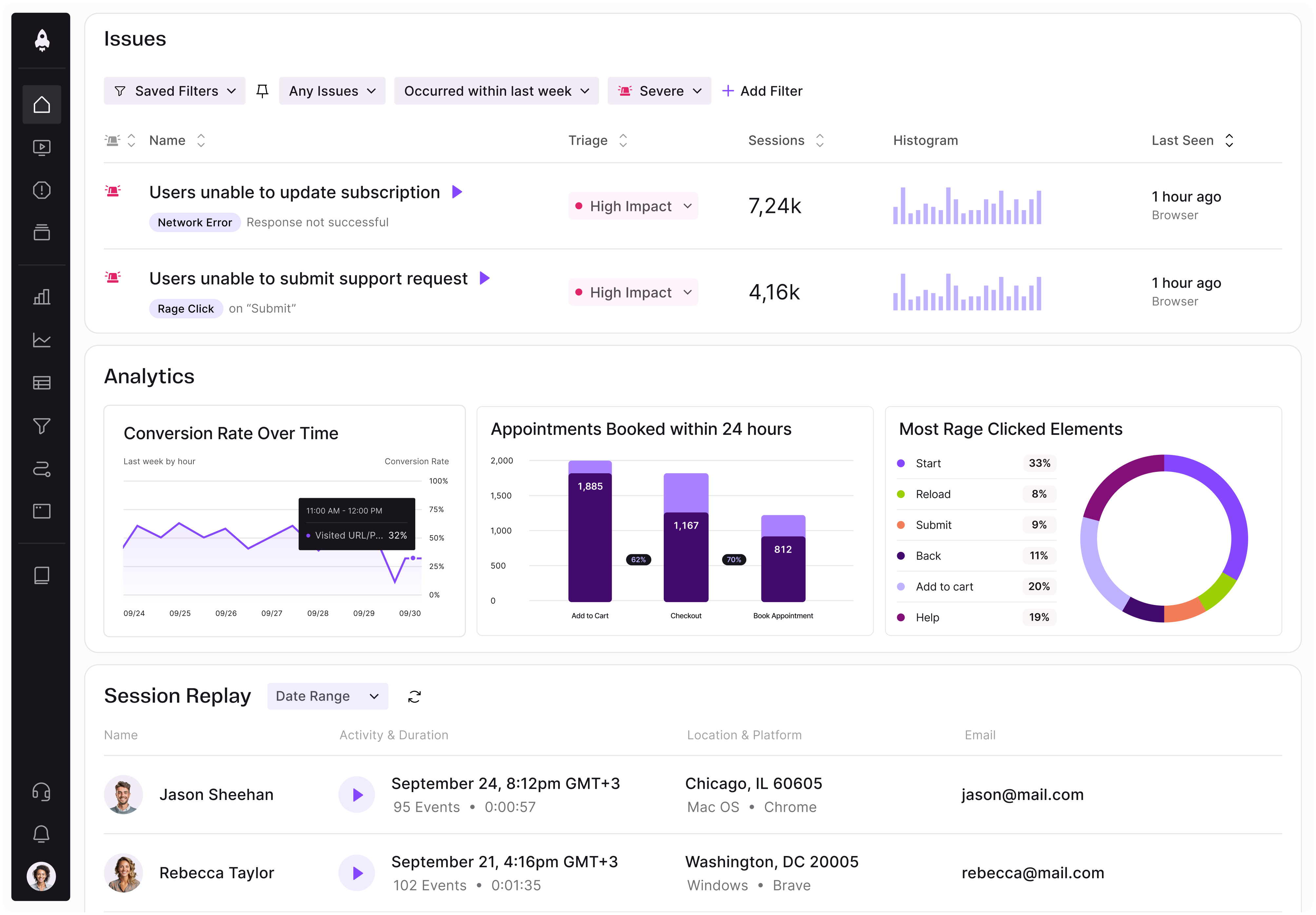

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.