Andrew Cheng is Vice President of Product Management at WellSky, a healthcare technology company. He began his career at Amazon in the smartwatches division. From there, Andrew pivoted into multiple areas within the company, including global operations integrations, pharmacy, and the Grand Challenge. Before his current role at WellSky, he served in leadership roles at CommerceHub, a commerce network, and Ridgewood, an Amazon consulting firm.

In our conversation, Andrew talks about how he views career goals and shares examples of times when he’s made short-term trade-offs for long-term career opportunities. He also discusses his experience working toward his long-term goal of driving a positive impact at scale.

I was quite fortunate to move into product management fairly early on in my career. When I joined Amazon, I was on the retail business side of the company. But, within three or four months, I had the opportunity to move over to product management for smartwatches and wearable technology.

As I consider the broader process of considering what my career has looked like, for each transition, I’ve always asked myself, “What does success look like for me? What is my personal definition of where I want to go in my career?” There have been multiple types of exercises that I’ve leveraged, whether that has been following role models that I look up to or building a 10 or 20-year, forward-looking, theoretical resume to outline what I want to accomplish in my career.

I’ve used the outputs of those exercises to define the target end state I want to arrive at. From there, it’s a matter of working backward to understand what it takes to ladder up to that type of outcome.

The process for setting your career expectations has a few components. Primarily, it’s valuable to have an intentional perspective on where it is that you want to go, but appreciate that along that path, you may come across new things — new pieces of information, new learnings, and new opportunities. Those will create emergent opportunities and paths as well. It’s important to balance those two things together.

You may come into it with a point of view on your intentional strategy, but you will likely end up adapting that or taking advantage of something that comes across your path. Sometimes, you’ll find that perhaps what you had in mind originally was not actually the right fit for you. It’s a combination of leveraging intentional and emergent strategies, working backwards to have a point of view on what you need to do in the first steps, and understanding how those will cascade to get you to where you want to go.

I say it’s a combination of those things. When I was younger, I had a goal for what I wanted to accomplish in my career and in my life, which was driving a positive impact at scale. I had originally thought about a career in chemistry, biotech, or pharmaceutical development. I would say that was my intentional strategy. I took a lot of science courses and did lab work, but found that chemistry was not my strong suit.

With that learning and my ultimate goal of positive impact in mind, I spent time considering how that could line up with some of the skills and competencies that I had. I felt those were in the realm of innovative and creative thinking, as well as communication and leadership. That led me to consider a career in politics, law, and business, which became my intentional strategy for a while until a more emergent opportunity came around with my work at Amazon.

Also, a few years ago, I read the book, How Will You Measure Your Life? By Clay Christensen. That book put a lot of mental models that I had considered for a long time into words. The language that I’m mentioning around emergent and intentional strategies is laid out in that book.

A pivotal moment was my consideration of leaving the Amazon pharmacy team that I had been a part of for a couple of years. I was thinking of moving over to a new team and organization in the Grand Challenge at Amazon. I consider that pivotal because from a career growth standpoint, with respect to the more traditional path of promotion, I set myself back by over a year with that move. But I did it because I felt that the Grand Challenge and the work that they were doing was more aligned with my own long-term goals around positive social impact.

I also felt like the opportunity that particular role afforded me would help me to develop specific particular skills unique from those in Amazon pharmacy. I was willing to make the trade-off of short-term career growth for longer-term skills and opportunities. In joining the Grand Challenge and in helping to start up that new team, I learned a tremendous amount. I was the founding member and chief of staff setting up a new organization at Amazon. Building and hiring that entire team was a really valuable experience that would have been difficult to approximate in the Amazon pharmacy world.

The decision to come here was similarly motivated by my desire to work in an industry that was more impact-driven. I was looking for opportunities to get into healthcare. I took a meaningful compensation cut, which can be hard to do sometimes. But I wanted to learn more about the healthcare industry and space, and this type of work is important to me.

As I look at the ways that I’ve considered growth and opportunities in my career, some peaks and valleys take place in a lot of different facets of what comprises a job. Some roles might be lower in pay than others. Others may be higher or lower in learning opportunities, mentorship, and leadership. It’s OK to take a step back in one of those domains if you feel like you can take a large step forward in another. It’s the long-term composite score or consideration that’s most important.

Certainly. It’s particularly valuable, even on a fixed cadence, to step back and think about what you have been able to accomplish. From there, you can reevaluate the intentional strategy you want to pursue. Those transitional moments are pivotal in considering how the emergent opportunity interplays with your intentional strategy but setting aside harboring the time to reflect on just where your intentional strategy is and how it’s going is super important.

There are opportunities to effectively structure that. I try to take one day off each quarter to just sit down and think about how I feel things are progressing. What are the items that I have struggled with and what are the things that I feel like I’ve been able to do well? Around the classical annual review cycle, those are good opportunities as well to be reflective about the direction that you’re going and how you want to approach your own career.

I would characterize it mostly as intentional and growth-focused. I’m a firm believer in sustainable development and empowering individuals not just to succeed in their existing roles, but to also prepare for their future ones. Also, you earn a lot of trust in being able to actually do the most tangible boots-on-the-ground work. Effective leadership for me is balancing that latitude and ability to own something and working with somebody to help set the right expectations to support them.

Personal brand is reflected in the way that you conduct yourself and how you interact with others. At the end of the day, your personal brand is not necessarily something you get the choice to define — it’s defined by those around you. Even if you have good intentions, the implementation is ultimately reflected in the people that you work with. For me, the brand that I look to instill is around being thoughtful, structured, and logical in the way that I break down problems.

That’s important because it helps support a brand of being fair and trustworthy. I’m comfortable giving people answers that they may not be happy with as long as they understand why I came to that answer. I’m open to fielding perspectives that might challenge some of the ways that I’ve thought about my problem or solution, and that’s OK. Part of the process of earning trust with others is being transparent in how you are thinking about a problem space, being open to their perspective, and being willing to change your mind.

The last aspect of my personal brand is being somebody who cares. I feel very strongly about having my team’s backs. At the end of the day, we’re all individuals — we have lives that take place in, around, and outside of our work, and it’s important not to lose sight of that. There’s a direct link between the quality of your work life and how it impacts your mood. That’s a very important part of my own personal brand.

I like to be very transparent with the teams and leaders that we work with. Generally, people are quite open and understanding that life happens. If you are proactive in saying that these are things that you’re struggling with or that you need support in these areas, you can manage those and offset them.

I remember when I was in the middle of my time at Amazon. I sat down with my director and asked, “How do you effectively compartmentalize things that are happening in your personal life from impacting your work?” He said, “Well, you can’t really. To some extent, those are things that are always going to be pervasive and it’s difficult.”

He provided a framework around actionability and occupancy of mind space to say that, if there’s something that I am worried about, I have to ask myself if there’s anything that I can do about it. If there is, then I will take that action. But if I’m thinking a lot about something that I actually have no control and action over, I will do my best to try and set that aside.

There was a period in my career where I wanted to believe that I could push through some of the personal challenges that I was facing. That desire led me to articulate that I had a handle on things. But those items in my personal life ended up being more challenging than I had hoped they would be. I learned a lot about being able to raise my hand and be open about what I can and can’t do.

Working on building out the initiative in the Grand Challenge at Amazon was very impactful for me. I had never been responsible for helping to build out an entire organization or shape the culture and tenets that we wanted to operate on. That domain space was totally new to Amazon — no one at the company had the expertise or knowledge that we needed to build our solution and product effectively. We had to leverage several different subject matter experts, such as expert interview networks and consultants.

This is something I’m proud of because we built a very strong, healthy, and positive team culture during COVID, which added complexity. I had the opportunity to live out my long-term dream. I mentioned earlier that I had wanted to pursue pharmaceuticals or biotech. When I was a kid, I said, “I’m going to cure cancer.” The project I was able to work on in the Grand Challenge was not actually curing cancer, but in the same vein, had a huge impact and innovation in the world of medicine. The opportunity to functionally realize something that I had dreamed about as a child was really fulfilling.

It was also interesting to come out the other side and appreciate that that wasn’t actually where I wanted to take my longer-term career. That realization was insightful, both because it was a wonderful opportunity to be able to live that dream, but also because it was valuable to see how my perspective had evolved and grown over time.

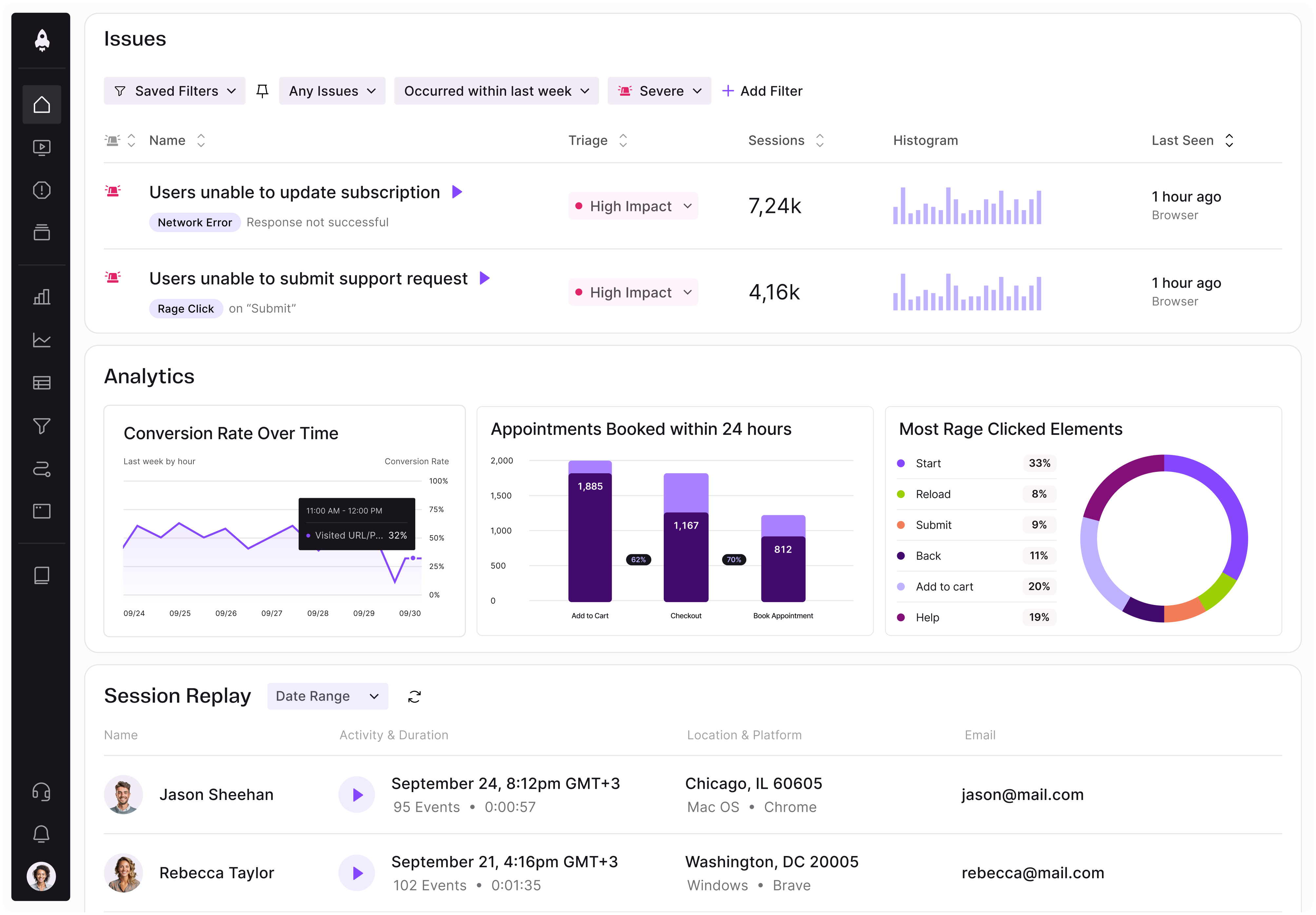

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

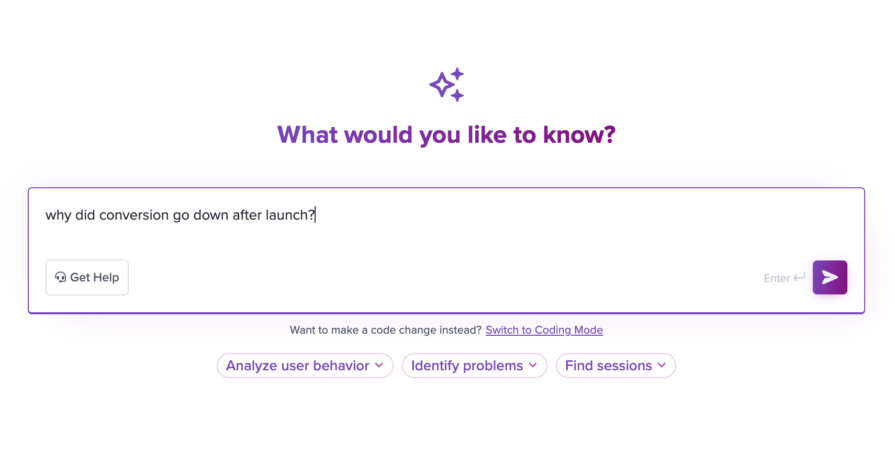

Introducing Ask Galileo: AI that answers any question about your users’ experience in seconds by unifying session replays, support tickets, and product data.

The rise of the product builder. Learn why modern PMs must prototype, test ideas, and ship faster using AI tools.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.