Testing assumptions is one of your most important responsibilities as a product manager. It’s also one of the most ambiguous.

In this article, I’ll try to make the tasks of identifying, prioritizing, and testing assumptions more tangible to help you de-risk your products more effectively.

Let’s start by breaking down why assumptions are so important for product managers.

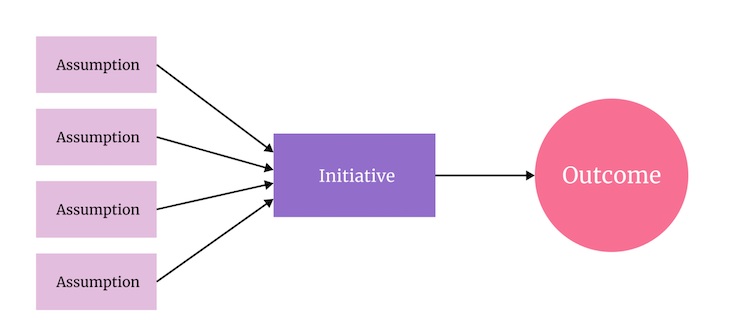

Product managers are responsible for driving specific outcomes. We do that by kickstarting a set of initiatives, be it a new feature, redesign, promo campaign, pricing change, and so on.

All these initiatives are based on a set of underlying assumptions. You assume things like:

If you get these assumptions right, you win. You end up with a successful initiative that drives the outcome. If you get them wrong, though, you end up with an outcome below your expectations or, worse, a total failure.

The biggest problem is that PMs often neglect to think about specific assumptions. Most product managers are still problem- and solution-oriented. As a result, they usually test whole initiatives rather than underlying assumptions.

There are two problems with that:

Bad product managers focus on solutions. Good product managers focus on problems. Great product managers focus on assumptions.

There are various ways to work with assumptions. One of the most common approaches is to use an assumption map.

The basic process of working with assumptions consists of three steps:

The very first step is to uncover and identify as many assumptions as you can.

The truth is, you probably won’t capture all assumptions — there will always be some hidden assumption that you miss or don’t take into consideration, but that’s OK.

Let’s start with understanding different types of assumptions, which should help you pinpoint specific assumptions.

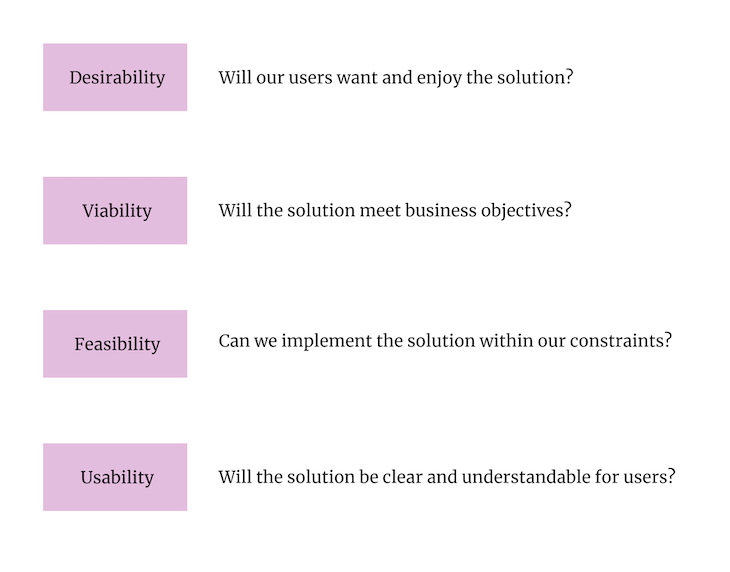

Although PMs and organizations categorize assumptions differently, the most common scheme distinguishes four types of assumptions:

The most straightforward way to identify assumptions is to ask yourself, “What must be true for the idea to be viable/desirable/feasible/usable?”

To put it into perspective, imagine you’re building an app that allows users to order a dog walker in an Uber-like fashion. Now let’s try spotting some assumptions for your assumption map:

The above is just an example of the different types of assumptions you might make. In reality, there would be dozens more.

Use the viability/desirability/feasibility/usability labels as prompts to focus your thinking, but don’t over-sweat it. For example, you could debate whether “the time between an order and fulfillment should be within 60 minutes” is actually a desirability or usability assumption. But, in practice, it doesn’t matter.

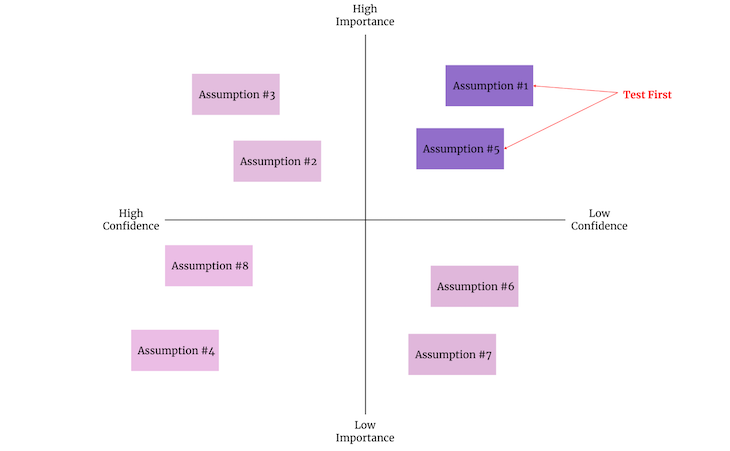

The assumption map is a powerful visual representation of all your assumptions and their relative importance/evidence level.

Importance refers to how critical the assumption is for the success of the initiative.

To answer this question, try asking yourself a follow-up question: “What would happen if the assumption turned out to be false?”

If the answer is:

Confidence answers the question, “How much evidence do we have to claim that the assumption is true?”.

I’d say if you have:

These are just examples of how you can measure confidence and importance. There are dozens of frameworks and approaches to assessing these two values, so use whatever you find fit.

Based on importance and confidence scores, map it on a 2×2 matrix and, voila, you have an assumption map:

The assumption map visualizes all known assumptions and gives you a picture of how well-tested and critical they are. It doesn’t have to be scientific and super-precise; the goal here is to get a high-level picture of the type of assumptions you have.

Based on where the assumptions lay on your map, take the following next steps:

The assumptions in the high importance/low confidence quadrant should be your top focus. These assumptions should be tested before you commit to an idea or build the first version of the product.

Although an actual launch is an ultimate validator, you should test these ideas as much as possible to avoid waste (we’ll see how later).

Assumptions that are low in both importance and confidence are not essential to testing, although you should still consider them.

Consider importance vs. effort to make decisions; if an idea is relatively simple to validate/test, do so. But if it would require a lot of effort to test the idea, it’s probably not worth it.

Even if an assumption is already high in confidence, if it’s critical to the product’s success, I’d still recommend looking for ways to validate it even further. Try to push it as far left on the assumption map as possible.

Granted, you won’t ever be 100 percent certain until you launch the product. Here, again, should make importance-vs.-effort decisions to help you determine when good is enough is good enough.

If an assumption is both low in importance and highly tested, just ignore it. You have bigger fish to fry.

The most efficient way to de-risk your ideas and initiatives is to test individual assumptions and increase your confidence in them.

Apart from building confidence, testing assumptions also brings you additional learnings and insights that’ll help you shape the product’s further direction.

Although testing assumptions is a topic that deserves an article on its own, here are some examples of techniques you can use for validating assumptions:

Most desirability assumptions can be tested by simply talking to users. Make sure you understand your target persona as much as you can. Interview, survey, and observe them in action.

Usability assumptions are often the easiest to test. Just build a prototype and see how users interact with it. Is it intuitive and understandable, or do they struggle?

Market sizing, competitive analysis, and market dynamics research can help you test various types of assumptions.

For example, if there are competitors on the market that do well with similar initiatives, there’s probably a desirability for that on the market. But if the competitors are well-established and barriers to entry are high, entering the market might not be economically viable.

A technical investigation is the main way to test feasibility assumptions. It can be an actual investigation (a developer doing research on a subject and estimating effort), a simple proof of concept, a documentation review, and so on.

Technical investigation usually answers two questions:

Committing a few hours to a technical investigation can help you avoid sinking hundreds of hours into the unfeasible idea.

Building an MVP is one of the most powerful ways to verify assumptions.

Although many associate the term MVP with the first version of the product, there are other ways to define your MVP. For example, you could try:

…and so on, depending on the assumptions you want to validate.

Assumption maps are powerful tools that lend structure to your validation and de-risking strategy. However, you get most of this technique’s benefits if you use it as a long-term, living artifact.

Over time, you’ll identify new assumptions and disregard others. Some previously unimportant assumptions might become supercritical under new circumstances, and you gain/lose confidence in assumptions as you learn over time.

Treating your assumption map as another type of weekly “dashboard” allows you to navigate product decisions more effectively, thanks to knowing where you should focus your learnings at any given moment.

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Great product managers spot change early. Discover how to pivot your product strategy before it’s too late.

Thach Nguyen, Senior Director of Product Management — STEPS at Stewart Title, emphasizes candid moments and human error in the age of AI.

Guard your focus, not just your time. Learn tactics to protect attention, cut noise, and do deep work that actually moves the roadmap.

Rumana Hafesjee talks about the evolving role of the product executive in today’s “great hesitation,” explores reinventing yourself as a leader, the benefits of fractional leadership, and more.