Errors are part of the programming journey. By producing errors, we actually learn how not to do something and how to do it better next time.

In JavaScript, when code statements are tightly coupled and one generates an error, it makes no sense to continue with the remaining code statements. Instead, we try to recover from the error as gracefully as we can. The JavaScript interpreter checks for exception handling code in case of such errors, and if there is no exception handler, the program returns whatever function caused the error.

This is repeated for each function on the call stack until an exception handler is found or the top-level function is reached, which causes the program to terminate with an error.

In general, exceptions are handled in two ways:

function openFile(fileName) {

if (!exists(fileName)) {

throw new Error('Could not find file '+fileName); // (1)

}

...

}

try {

openFile('../test.js');

} catch(e) {

// gracefully handled the thrown expection

}

Let’s dive into these actions in more detail.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

If you’ve been using JavaScript for a long time, you may have seen something like ReferenceError: fs is not defined. This represents an exception that was thrown via a throw statement.

throw «value»;

// Don't do this

if (somethingBadHappened) {

throw 'Something bad happened';

}

There is no restriction on the type of data that can be thrown as an exception, but JavaScript has special built-in exception types. One of them is Error, as you saw in the previous example. These built-in exception types give us more details than just a message for an exception.

The Error type is used to represent generic exceptions. This type of exception is most often used for implementing user-defined exceptions. It has two built-in properties to use.

messageThis is what we pass as an argument to the Error constructor — e.g., new Error('This is the message'). You can access the message through the message property.

const myError = new Error(‘Error is created’) console.log(myError.message) // Error is created

stackThe stack property returns the history (call stack) of what files were responsible for causing the error. The stack also includes the message at the top and is followed by the actual stack, starting with the most recent/isolated point of the error to the most outward responsible file.

Error: Error is created at Object. (/Users/deepak/Documents/error-handling/src/index.js:1:79) at Module.compile (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:689:30) at Object.Module.extensions..js (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:700:10) at Module.load (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:599:32) at tryModuleLoad (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:538:12) at Function.Module._load (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:530:3) at Function.Module.runMain (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:742:12) at startup (internal/bootstrap/node.js:266:19) at bootstrapNodeJSCore (internal/bootstrap/node.js:596:3)

Note: new Error('...') does not do anything until it’s thrown — i.e., throw new Error('error msg') will create an instance of an Error in JavaScript and stop the execution of your script unless you do something with the Error, such as catch it.

Now that we know what exceptions are and how to throw them, let’s discuss how to stop them from crashing our programs by catching them.

try-catch-finallyThis is the simplest way to handle the exceptions. Let’s look at the syntax.

try {

// Code to run

} catch (e) {

// Code to run if an exception occurs

}

[ // optional

finally {

// Code that is always executed regardless of

// an exception occurring

}

]

In the try clause, we add code that could potentially generate exceptions. If an exception occurs, the catch clause is executed.

Sometimes it is necessary to execute code whether or not it generates an exception. Then we can use the optional block finally.

The finally block will execute even if the try or catch clause executes a return statement. For example, the following function returns false because the finally clause is the last thing to execute.

function foo() {

try {

return true;

} finally {

return false;

}

}

We use try-catch in places where we can’t check the correctness of code beforehand.

const user = '{"name": "Deepak gupta", "age": 27}';

try {

// Code to run

JSON.parse(params)

// In case of error, the rest of code will never run

console.log(params)

} catch (err) {

// Code to run in case of exception

console.log(err.message)

}

As shown above, it’s impossible to check the JSON.parse to have the stringify object or a string before the execution of the code.

Note: You can catch programmer-generated and runtime exceptions, but you can’t catch JavaScript syntax errors.

try-catch-finally can only catch synchronous errors. If we try to use it with asynchronous code, it’s possible that try-catch-finally will have already been executed before the asynchronous code finishes its execution.

JavaScript provides a few ways to handle exceptions in an asynchronous code block.

With callback functions (not recommended) , we usually receive two parameters that look something like this:

asyncfunction(code, (err, result) => {

if(err) return console.error(err);

console.log(result);

})

We can see that there are two arguments: err and result. If there is an error, the err parameter will be equal to that error, and we can throw the error to do exception handling.

It is important to either return something in the if(err) block or wrap your other instruction in an else block. Otherwise, you might get another error — e.g., result might be undefined when you try to access result.data.

With promises — then or catch — we can process errors by passing an error handler to the then method or using a catch clause.

promise.then(onFulfilled, onRejected)

It’s also possible to add an error handler with .catch(onRejected) instead of .then(null, onRejected), which works the same way.

Let’s look at a .catch example of promise rejection.

Promise.resolve('1')

.then(res => {

console.log(res) // 1

throw new Error('something went wrong'); // exception thrown

})

.then(res => {

console.log(res) // will not get executed

})

.catch(err => {

console.error(err) // exception catched and handled

});

async and await with try-catchWith async/await and try-catch-finally, handling exceptions is a breeze.

async function() {

try {

await someFuncThatThrowsAnError()

} catch (err) {

console.error(err)

}

})

Now that we have a good understanding of how to perform exception handling in synchronous and asynchronous code blocks, let’s answer the last burning question of this article : how do we handle uncaught exceptions?

The method window.onerror() causes the error event to be fired on the window object whenever an error occurs during runtime. We can use this method to handle the uncaught exception.

Another utility mode for onerror() is using it to display a message in case there is an error when loading images in your site.

<img src="testt.jpg" onerror="alert('An error occurred loading yor photo.')" />

The process object derived from the EventEmitter module can be subscribed to the event uncaughtException.

process.on("uncaughtException", () => {})`

We can pass a callback to handle the exception. If we try to catch this uncaught exception, the process won’t terminate, so we have to do it manually.

The uncaughtException only works with synchronous code. For asynchronous code, there is another event called unhandledRejection.

process.on("unhandledRejection", () => {})

Never try to implement a catch-all handler for the base Error type. This will obfuscate whatever happened and compromise the maintainability and extensibility of your code.

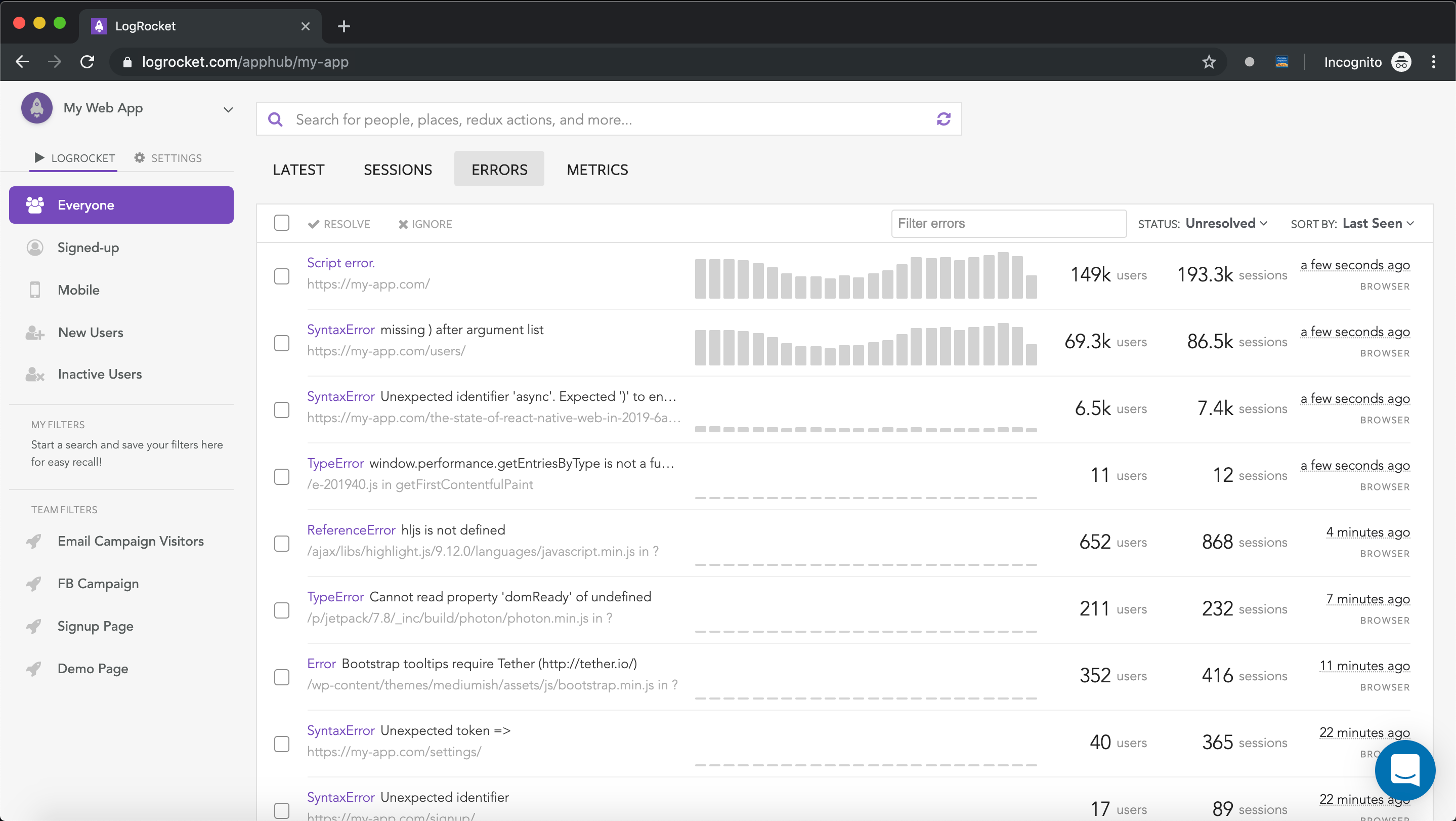

Handling JavaScript exceptions is the first step — actually fixing them is where things get tough. LogRocket is a frontend application monitoring solution that lets you replay JavaScript errors as if they happened in your own browser. LogRocket lets you replay sessions with a JavaScript exception to quickly understand what went wrong. It works perfectly with any app, regardless of framework, and has plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stacktraces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. It also instruments the DOM to record the HTML and CSS on the page, recreating pixel-perfect videos of even the most complex single-page apps.

Let’s review some of the main points we discussed in this article.

throw statement is used to generate user-defined exceptions. During runtime, when a throw statement is encountered, execution of the current function will stop and control will be passed to the first catch clause in the call stack. If there is no catch clause, the program will terminateError, which returns the error stack and messagetry clause will contain code that could potentially generate an exceptioncatch clause will be executed when exceptions occurasync-await with try-catchWhen done properly throughout, exception handling can help you improve the maintainability, extensibility, and readability of your code.

Compare the top AI development tools and models of February 2026. View updated rankings, feature breakdowns, and find the best fit for you.

Broken npm packages often fail due to small packaging mistakes. This guide shows how to use Publint to validate exports, entry points, and module formats before publishing.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 11th issue.

Cut React LCP from 28s to ~1s with a four-phase framework covering bundle analysis, React optimizations, SSR, and asset/image tuning.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now