As I was surfing the internet, I came across this tweet. It seems that front-end devs are tired of requesting for APIs every now and then. 😄

The only reason GraphQL hasn’t taken off like a rocket is the backend devs who don’t understand the mess they make for the front end code and think front end is a lesser form of programming.

— Ryan Florence (@ryanflorence) November 8, 2018

The first time I interacted with GraphQL, I fell in love with it. Why? GraphQL gives you room to build your APIs with ease and saves you from doing the same thing over and over again. How? Let’s find out.

I’ll assume you have basic knowledge in the following:

Let’s take a look at the comparison between GraphQL and REST.

To get the full picture of this article, I will want you to clone the repository for this project, it contains both the server side and the client side.

In this article, we will look at the following points

GraphQL is query language which helps hand over the key to the door of your APIs to a visitor (client), with your permission of course. Well, if it’s not managed properly, your visitor may mess things up.

In one way or the other, your application will have to interact with other applications. This can only be done by exposing some or all of your APIs. One of the ways to achieve this is by using building your app using REST. By the end of this article, we will both see the reason why you should use GraphQL in your next application.

GraphQL is a query language for APIs and a runtime for fulfilling those queries with your existing data. GraphQL provides a complete and understandable description of the data in your API, gives clients the power to ask for exactly what they need and nothing more, makes it easier to evolve APIs over time, and enables powerful developer tools.

REST Vs GraphQL

route while REST has multiple routes. As the client’s needs increases, the REST endpoints keep increasing.HTTP verbs (POST, PUT, GET etc) but GraphQL has also got us covered as it does not require such things.interactive API documentation out of the box.resolve data as far as you can in GraphQL but not in case of REST. It must surely come with a new (endpoint).version your API since the single route will not change but you need to be concerned about how you should version your APIs while using REST when update keeps coming.Enough of the sermon!

Let’s take a look at a typical GraphQL documentation. Feel free to copy and paste the snippet to get the feel on your machine.

In the course of this project, we will be exploring GraphQL with Apollo. Apollo supports both NodeJs and VueJs. 😃

Let’s take a look at what the demo for our project looks like, this should give you an idea of what lies ahead. You can also set it up.

Recipe demo

There are four major components we will be focusing on which are:

schema for every model. In this project, we have just two models (recipe and user).const recipeSchema = new mongoose.Schema({

name: {

type: String,

},

description: {

type: String,

},

difficultyLevel: {

type: Number,

},

fileUrl: {

type: String

},

steps: [{

type: String

}],

averageTimeForCompletion: {

type: Number,

},

userId: {

type: mongoose.Schema.Types.ObjectId,

ref: 'User'

}

}, { timestamps: true });

export const Recipe = mongoose.model('Recipe', recipeSchema);schema on database level

We also have a schema on the API level which will conform to the above database schema. This schema also forms like a validator on top of the database schema. A query that has types not recognized by GraphQL will bounce.

type Recipe {

id: ID!

name: String!

description: String!

difficultyLevel: Int!

image: String!

steps: [String]!

averageTimeForCompletion: Int!

user: User!

}schema on API level

In writing a schema, there are different object Types GraphQL supports: Int, Float, String, Boolean, ID just like _id in MongoDB. It also supports List in case your database schema has a list of objects and lot more.

! sign ensures an object does not return a null value. Always use it when you are double sure, a value will be returned. If it appears to be used and the value is null, an error will be thrown. In the above snippet, we are not expecting our id of type ID to be null.

We can also have our own custom type just like the way we have a File type.

type File {

id: ID!

url: String!

}2.Queries: In REST, the standard way of fetching data is to use GET. The same concept is applied to GraphQL queries. We use Query where we need to fetch data. Query can only be defined once in GraphQL.

For better understanding, each GraphQL component has its own file in the project. In the recipe project, the keywordQuery is used more than once.

Let’s look at how to write a query to get the property of a user in the session.

type User {

id: ID!

email: String!

name: String!

token: String

createdAt: String!

updatedAt: String!

}

type Query {

getMe: User!

}query user

Since we have declared query in user resource, we will also have to declare query in recipe resource. You should be aware it’s going to throw an error? Well, we are covered. For keyword Query to be used more than once, it needs to be extended using the keyword extend.

For us to get the user recipes, we need a user ID associated with that recipe. GraphQL query can also accept arguments.

extend type Query {

Recipe(id: ID!): Recipe!

Recipes: [Recipe]!

}recipe

There are two different queries above. The first one gets a recipe using an argument id of type ID which must not be null, while the latter returns all recipes in the system.

3. Mutation: An API is beyond just fetching, at some point, data must be stored, updated or deleted to keep our platform alive. To perform this operation (POST, PUT, DELETE etc), its best to declare it under mutation.

type Mutation {

createUser(email: String!, name: String!, password: String)

}create a user (mutation)

The createUser mutation could have been written outrightly but I prefer using the variable declaration style. O yes, you can also declare a variable for your mutation.

In cases where you need a client to supply an input before you send a response, a variable will come in handy.

type Mutation {

createUser(input: NewUser!): User!

loginUser(input: LoginUser!): User!

}user login and registration

Variables can come with any type of form. As long as GraphQL is informed by creating or declaring your variable type, there won’t be an alarm. 😉

In the above mutation, we have both loginUser and createUser which accepts an input of type NewUser which must return a type User and type LoginUser which also returns a User . We already saw what a User looks like above.

inputis a form of variable which serves a parameter with a declared type.

input LoginUser {

email: String!

password: String!

}

input NewUser {

email: String!

name: String!

password: String!

}Login and registration type

type Recipe {

id: ID!

name: String!

description: String!

difficultyLevel: Int!

image: String

steps: [String]!

averageTimeForCompletion: Int!

user: User!

}

input NewRecipe {

name: String!

description: String!

difficultyLevel: Int!

image: Upload

steps: [String]!

averageTimeForCompletion: Int!

}

input UpdateRecipe {

id: ID!

name: String

description: String

difficultyLevel: Int!

image: String

steps: [String]

averageTimeForCompletion: Int!

}

input DeleteRecipe {

id: ID!

}

# query is use when you want to get anything from

#the server just like (GET) using REST

extend type Query {

Recipe(id: ID!): Recipe!

Recipes: [Recipe]!

}

# performing actions (that requires DELETE, PUT, POST)

#just as in REST requires a mutation

extend type Mutation {

deleteRecipe(input: DeleteRecipe!): Recipe!

updateRecipe(input: UpdateRecipe!): Recipe!

newRecipe(input: NewRecipe!): Recipe!

}recipe schema

In the above snippet, a user can decide to delete a recipe, update a recipe and create a new recipe based on the declarations we have in Mutation.

Did you notice a type that was not declared but used Upload? But GraphQL seems to be cool with it. We shall hash this out in the file section.

4. Resolvers: Now that we have declared out types, mutations, and queries. How does this connect with the client’s request in relation to our database?

Let’s take a look at this flow…

So in GraphQL, we have the scalar types (Strings,Integers, Booleans, Float, Enums). If we are lucky enough to match our database object with the types we have, GraphQL will resolve that for us.

Let’s handle the actions we have declared in our mutations. Remember the argument we declared in our mutation is input. Whatever we are expecting from the client will be found in the variable input.

import { User } from './user.model';

import { Recipe } from '../recipe/recipe.model';

import { signIn, verify } from '../../modules/auth';''

const loginUser = async(root, { input }) => {

const { email, password } = input;

const user = await User.findOne({ email }).exec();

const errorMsg = 'Wrong credentials. Please try again';

if(!user) {

throw new Error (errorMsg);

}

if(user.comparePassword(password)) {

user.token = signIn({ id: user._id, email: user.email });

return user;

}

else{

throw new Error (errorMsg);

}

};Login user

Let’s take a moment to look at the arguments for Queries and Mutations. Using loginUser as an example.

There are four major arguments in every resolver (rootValue, arguments, context and info).

rootValue: it is mostly used when handling nested resolvers (child branch of a main branch).type User {

id: ID!

email: String!

name: String!

token: String

recipes: [Recipe]!

createdAt: String!

updatedAt: String!

}user type

Look at the above type, there is an object we didn’t declare in our database model. This means GraphQL expects us to resolve (process it and assign a value).

recipes will be treated as a nested resolver. The rootValue above the branch is the User. The advantage of this is fetching recipes created by a user.

User: {

recipes(user) {

return Recipe.find({ userId: user.id }).exec()

}

}nested resolver

arguments: It holds arguments passed from the client. In our defined mutations, we expected the clients to pass in an inputcontext: This holds any data that needs to be shared across your resolvers. In this project, we passed in the user that is verified to the contextinfo:It’s the only argument we might never use. It’s the raw GraphQL queryFor the loginUser, the user passes the email and password destructed from argument object and a user is returned just as we declared in the mutation (User!) if the credential is correct else we throw an error.

The declaration we have in the Mutation type (server/api/resources/user/user.graphql file) must also be the same passed to the resolver.

export const userResolvers = {

Query: {

getMe

},

Mutation: {

createUser, //createUser: createUser

loginUser //loginUser: loginUser

},

User: {

recipes(user) {

return Recipe.find({ userId: user.id }).exec()

}

}

}user resolver

There are several ways we can authenticate our GraphQL application especially when we want to make a query or mutation operation public (loginUser and createUser).

We can secure it by either using REST for public routes and securing the single GraphQL route separately. Personally, I always go for this option because It provides flexibility to your application.

In this project, we authenticated GraphQL on a resolver level. When a user login successfully, a token generated using jwebtokens is returned to the client and is expected to be passed to the headers.

import { verify } from './api/modules/auth';

const setMiddleware = (app) => {

app.use(async (req, res, next) => {

try{

const token = req.headers.authorization || '';

const user = await verify(token);

req.user = user;

}

catch(e) {

console.log(e)

req.user = null;

}

next();

});

};

export default setMiddleware;The middleware cross-checks the header in every request, grabs the token, verifies and gives appropriate payload (user) if successful. The middleware is then passed into Apollo Server.

Since we are using express, apollo-server-express is our best tool to use.

setMiddleware(app); const path = '/recipe' graphQLRouter.applyMiddleware({ app, path});const secret = process.env.TOKEN_SECRET; const expiresIn = process.env.EXPIRES_IN || '1 day'; export const signIn = payload => jsonwebtoken.sign(payload, secret, { expiresIn }); export const verify = token => { return new Promise((resolve, reject) => { jsonwebtoken.verify(token, secret, {}, (err, payload) => { if(err){ return reject(err); } return resolve(payload); }) }) } export const throwErrorIfUserNotAuthenticated = user => {if(!user) throw new Error('hey!. You are not authenticated')}

Auth

This is the point, every player comes together. The GraphQL tag (gql) makes it easier to write and combine schema together.

import { ApolloServer, gql } from 'apollo-server-express';

import merge from 'lodash.merge'

import { userType, userResolvers } from './resources/user';

import { recipeType, recipeResolvers } from './resources/recipe';

import { fileType } from './resources/file';

const typeDefs = gql`${userType}${recipeType}${fileType}`;

export const graphQLRouter = new ApolloServer(

{

typeDefs,

resolvers: merge({}, userResolvers, recipeResolvers),

context: ({req, res})=> ({ user: req.user })

}

);For every resolver, we check if the user is null or not, once its null, the client is bounced. The system tells the client to authenticate the request.

const getRecipe = (root, { id }, { user }) => {

throwErrorIfUserNotAuthenticated(user);

return Recipe.findById(id).exec();

}; Check if user has permission to access this resolver

Apart from sending simple data, we will one way or the other want to upload a file. Apollo server 2.0 ~ has made life easier by handling Files out of the box. Upload scalar is recognized by GraphQL. It helps handle a variable file object. It is added to NewRecipe input to handle the file that comes with the request.

const createRecipe = async (root, { input }, { user }) => {

throwErrorIfUserNotAuthenticated(user);

// bring out the image from input for file processing

const { image, ...recipeObject } = await input;

let url = "";

if (image) {

const result = await uploadFile(image);

url = result.url;

}

const recipe = await Recipe.findOne({ name: input.name.toLowerCase() });

if (recipe) {

throw new Error("Recipe already exists!");

}

Object.assign(recipeObject, { image: url, userId: user.id });

return Recipe.create(recipeObject);

};create a new recipe

The file stream is being processed, when it’s done, the URL is being saved with the rest input object.

import cloudinary from "cloudinary";

import streamToBuffer from "stream-to-buffer";

cloudinary.config({

cloud_name: process.env.CLOUDINARY_CLOUD_NAME,

api_key: process.env.CLOUDINARY_API_KEY,

api_secret: process.env.CLOUDINARY_API_SECRET

});

export const uploadFile = async file => {

const { mimetype, stream } = await file;

// process image

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (!Object.is(mimetype, "image/jpeg")) {

throw new Error("File type not supported");

}

streamToBuffer(stream, (err, buffer) => {

cloudinary.v2.uploader

.upload_stream({ resource_type: "raw" }, (err, result) => {

if (err) {

throw new Error("File not uploaded!");

}

return resolve({ url: result.url });

})

.end(buffer);

});

});

};Let’s take a look at the doc. It can be accessed on http://localhost:3000/recipe if your port number is 3000 and your MongoDB is running locally. Once you can interact well with the doc, the client becomes very easy.

If you are familiar with sending data from Vue to a server, there is no big difference in using vue-apollo. All you just need to do is write out your queries. Vue-apollo handles the rest for you.

So, let’s set up our Vue-apollo:

import Vue from 'vue';

import VueApollo from "vue-apollo";

import apolloUploadClient from "apollo-upload-client"

import { InMemoryCache } from "apollo-cache-inmemory";

import { ApolloClient } from "apollo-client";

import { setContext } from "apollo-link-context";

Vue.use(VueApollo);

const baseUrl = "http://localhost:3000/recipe";

const uploadClientLink = apolloUploadClient.createUploadLink({

uri: baseUrl

});

const interceptor = setContext((request, previousContext) => {

const token = localStorage.getItem("token");

if(token) {

return {

headers: {

authorization: token

}

};

}

});

const apolloClient = new ApolloClient({

link: interceptor.concat(uploadClientLink),

cache: new InMemoryCache(),

connectToDevTools: true

});

const instance = new VueApollo({

defaultClient: apolloClient

});

export default instance;

view rawsetContext from apollo-link-context gives us access to intercept the request before it passes down to the server. Remember, we need to pass a token to the header so as to get access to authenticated resources.

Every response is cached. cache: new InMemoryCache(), from the demo shown above, when a new recipe is created, we expected it to reflect in the All recipes page with others. But the response was already cached. It returned the response fetched from memory instead. This has its pros and cons.

this.$apollo gives us access to Vue apollo as long as it has been added (Vue.use(VueApollo))to Vue.

Let’s create our queries:

import gql from "graphql-tag";

// user object pointing to loginUser to make the return response pretty

export const LOGIN_QUERY = gql`

mutation LoginUser($input: LoginUser!) {

user: loginUser(input: $input) {

token

}

}

`;

export const REGISTERATION_QUERY = gql`

mutation RegisterUser($input: NewUser!) {

user: createUser(input: $input) {

token

}

}

`;

export const ALL_RECIPES_QUERY = gql`

query {

recipeList: Recipes {

id

name

image

}

}

`;

export const GET_USER_QUERY = gql`

query {

user: getMe {

name

email

recipes {

id

name

image

}

}

}

`;

export const CREATE_RECIPE_QUERY = gql`

mutation createRecipe($input: NewRecipe!) {

newRecipe(input: $input) {

id

}

}

`;The structure of the queries here is what we are expecting on the server side, the response of the queries are based on choice.

GET_USER_QUERY gets the name, email, recipes (id, name, and image) of a user in the session.

apollo: {

user: query.GET_USER_QUERY

}apollo is added to the component to fetch a specific query tied to an object. The getMe query is tied to the user object.

On the my-recipe page, we don’t want the response to be from cached memory.

this.$apollo.queries.user.refetch();

refetch fetches the latest data from the server using the corresponding (user) query. This should be used with caution.

There are some interesting options that can be accessed from apollo such as loading state, errors, halting the query flow and so much more.

How do we handle mutation?

Let’s look at how to create a recipe:

Since we are interested in a single file, the file object is bound to image (part of the object going to the server).

onFileChange(e) {

const files = e.target.files || e.dataTransfer.files;

this.image = files[0];

}$this.apollo.mutate accepts mutation and its variable. since the server is requesting for input. An input object is passed to the variable.

async createRecipe() {

const recipeObject = {

name: this.recipeName,

description: this.description,

difficultyLevel: this.difficultyLevel

? parseInt(this.difficultyLevel)

: 0,

image: this.image,

steps: this.stepsList,

averageTimeForCompletion: this.averageTime

? parseInt(this.averageTime)

: 0

};

await this.$apollo

.mutate({

mutation: query.CREATE_RECIPE_QUERY,

variables: { input: recipeObject }

})

.then(({ data }) => {

this.$router.push({ name: "my-recipes" });

})

.catch(err => {

console.log(err);

this.error =

parseGraphqlError(err) || "Something went wrong. Try again...";

});

}Create a recipe

Like I said earlier, GraphQL is easy to set up, update and refactor compared to what we are used to (REST).

If your schema is not well designed, your client can make a recursive call to your schema. Avoid queries that will give the same result. For further information on what GraphQL with Apollo is all about, please check here. If you will like to explore more information on Vue Apollo, kindly check here.

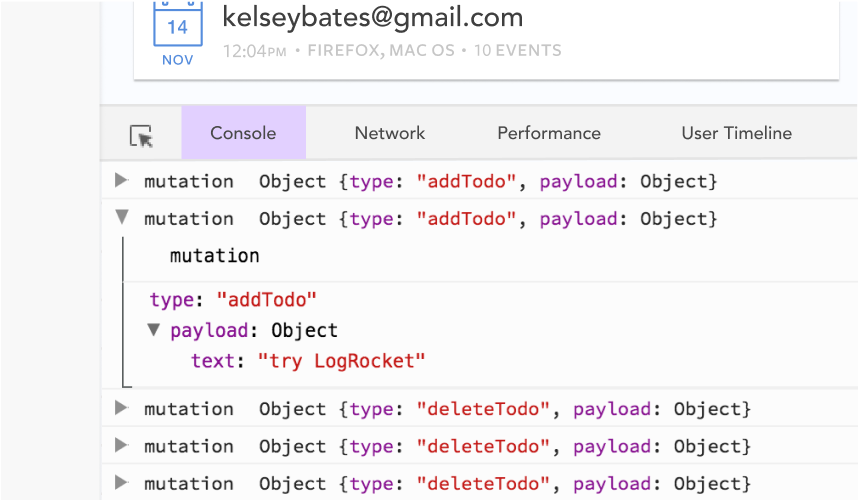

Debugging Vue.js applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are difficult to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking Vue mutations and actions for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug your Vue apps — start monitoring for free.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Learn how to integrate MediaPipe’s Tasks API into a React app for fast, in-browser object detection using your webcam.

Integrating AI into modern frontend apps can be messy. This tutorial shows how the Vercel AI SDK simplifies it all, with streaming, multimodal input, and generative UI.

Interviewing for a software engineering role? Hear from a senior dev leader on what he looks for in candidates, and how to prepare yourself.

Set up real-time video streaming in Next.js using HLS.js and alternatives, exploring integration, adaptive streaming, and token-based authentication.