Editor’s note: This guide to creating an async CRUD web service in Rust with warp was last updated on 24 April 2023 to reflect changes to Rust and to include new sections on why you should use warp in Rust and a section on testing the API. To learn more about Rust web frameworks, check out our list of the top Rust web frameworks.

In a previous post on this blog, we covered how to create a Rust web service using Actix and Diesel. This time around, we’ll create a lightweight, fully asynchronous web service using the warp web framework and tokio-postgres. Let’s get started.

Jump ahead:

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Warp is a lightweight Rust-based web framework that is both fast and secure. Warp is based on the well-known and battle-tested hyper HTTP library, which provides a robust and very fast basis for most Rust web frameworks.

Some of the key strengths of warp are its asynchronous request handling, powerful and flexible routing, and filtering capabilities, which allow developers to easily handle complex routing scenarios. Essentially, filters are just functions that can be composed together. In warp, they’re used for everything from routing to middleware to passing values to handlers. You can check out warp’s release post for a deeper dive.

Another interesting feature of Warp is its built-in support for WebSockets, which makes it easy to build real-time web applications. Even though warp is a newer framework compared to Rocket and Actix Web — which are the most popular Rust web frameworks — it has an active community and has over 8,000+ stars on GitHub. Warp is easy to use, even for building large-scale applications. Let’s get our hands dirty with some practicals to better understand how warp works.

Let’s start by setting up a warp project. To follow along, all you need is a reasonably recent Rust installation (v1.39+) and a way to run a PostgreSQL database (e.g., Docker). First, create your test project like this:

cargo new warp-example cd warp-example

Next, edit the Cargo.toml file and add the dependencies you’ll need, as shown below:

[dependencies]

tokio = { version = "0.2", features = ["macros"] }

warp = "0.2"

mobc-postgres = { version = "0.5", features = ["with-chrono-0_4"] }

mobc = "0.5"

serde = {version = "1.0", features = ["derive"] }

serde_derive = "1.0"

serde_json = "1.0"

thiserror = "1.0"

chrono = { version = "0.4", features = ["serde"] }

In case you’re wondering what all of this means, refer to this code:

tokio is our async runtime, which we need to execute futures warp is our web framework mobc / mobc-postgres represents an asynchronous connection pool for our database connections serde is for serializing and deserializing objects (e.g., to/from JSON) thiserror is a utility library we’ll use for error handling chrono represents time and date utilities

To avoid just dumping everything into one file, let’s add a bit of structure to main.rs:

mod data; mod db; mod error; mod handler;

For each of these modules, we’ll also create a file (e.g., data.rs). For the first step, create a web server running on port 8000 with a /health endpoint that returns a 200 OK. In main.rs, add:

use warp::{http::StatusCode, Filter};

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let health_route = warp::path!("health")

.map(|| StatusCode::OK);

let routes = health_route

.with(warp::cors().allow_any_origin());

warp::serve(routes).run(([127, 0, 0, 1], 8000)).await;

}

In the above snippet, we defined our health_route, which matches on GET /health and returns 200 OK. Then, to demonstrate how to add middleware, set up this route with the warp::cors middleware, which allows the service to be called from any origin.

To finish setting up the server, use warp::serve along with the routes as parameters, and then use the .run() method to begin running the server on port 8000. Test whether it works by starting the application using cargo run and cURL, as shown below:

curl http://localhost:8000/health

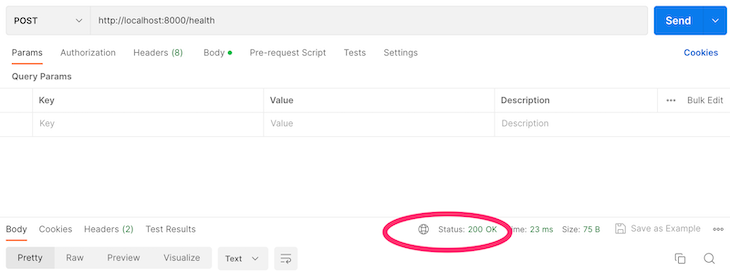

Here is a Postman example showing that it actually worked:

So far, so good! The next step is to set up your Postgres database and add a check for a working database connection in the /health handler. To start a Postgres database, you can either use Docker or a local Postgres installation. With Docker, you can simply execute — you must have Docker all set up before running the code below:

docker run -p 7878:5432 -d postgres:15.2

This command starts a Postgres database on port 7878 with user postgres, database postgres, and no password. Now that you have a running database, the next step is to talk to this database from your warp application. To do so, you can use mobc, an async connection pool, to spawn multiple database connections and reuse them between requests. Setting this up only takes a couple of lines. First, define some convenience types in main.rs:

use mobc::{Connection, Pool};

use mobc_postgres::{tokio_postgres, PgConnectionManager};

use tokio_postgres::NoTls;

type DBCon = Connection<PgConnectionManager<NoTls>>;

type DBPool = Pool<PgConnectionManager<NoTls>>;

Next, create your connection pool in db.rs:

use crate::{DBCon, DBPool};

use mobc_postgres::{tokio_postgres, PgConnectionManager};

use tokio_postgres::{Config, Error, NoTls};

use std::fs;

use std::str::FromStr;

use std::time::Duration;

const DB_POOL_MAX_OPEN: u64 = 32;

const DB_POOL_MAX_IDLE: u64 = 8;

const DB_POOL_TIMEOUT_SECONDS: u64 = 15;

pub fn create_pool() -> std::result::Result<DBPool, mobc::Error<Error>> {

let config = Config::from_str("postgres://[email protected]:7878/postgres")?;

let manager = PgConnectionManager::new(config, NoTls);

Ok(Pool::builder()

.max_open(DB_POOL_MAX_OPEN)

.max_idle(DB_POOL_MAX_IDLE)

.get_timeout(Some(Duration::from_secs(DB_POOL_TIMEOUT_SECONDS)))

.build(manager))

}

The create_pool function simply creates a Postgres connection string and defines some parameters for the connection pool, such as minimum and maximum open connections, as well as a connection timeout.

The next step is to simply build the pool and return it. At this point, no database connection is actually created, just the pool. Since we’re already here, let’s also create a function for initializing the database on startup:

const INIT_SQL: &str = "./db.sql";

pub async fn get_db_con(db_pool: &DBPool) -> Result<DBCon> {

db_pool.get().await.map_err(DBPoolError)

}

pub async fn init_db(db_pool: &DBPool) -> Result<()> {

let init_file = fs::read_to_string(INIT_SQL)?;

let con = get_db_con(db_pool).await?;

con

.batch_execute(init_file.as_str())

.await

.map_err(DBInitError)?;

Ok(())

}

With the get_db_con utility, we tried to get a new database connection from the pool. Don’t worry about the error right now — we’ll talk about error handling later on. To create a database table from the db.sql file on startup, the init_db function is called. This reads the file into a string and executes the query. The init query looks like this:

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS todo

(

id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL,

name VARCHAR(255),

created_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT (now() at time zone 'utc'),

checked boolean DEFAULT false

);

Back in our main function, we can now call our database setup functions, like this:

let db_pool = db::create_pool().expect("database pool can be created");

db::init_db(&db_pool)

.await

.expect("database can be initialized");

If any of the database setup codes fail, we can throw our hands up and panic because it won’t make sense to continue. Assuming it doesn’t fail, it’s finally time to tackle the primary goal of this section: to add a database check to the /health handler.

/health handlerTo do this, we need a way to pass the db_pool to the handler. This is a perfect opportunity to write our first warp filter. In main.rs, add the following with_db filter:

use std::convert::Infallible;

use warp::{Filter, Rejection};

fn with_db(db_pool: DBPool) -> impl Filter<Extract = (DBPool,), Error = Infallible> + Clone {

warp::any().map(move || db_pool.clone())

}

This is a simple extract filter. The above means that for any route (any()), you want to extract a DBPool and pass it along. If you’re interested in learning more about filters, the docs are quite helpful. The filter is then simply added to the handler definition with the .and() operator:

let health_route = warp::path!("health")

.and(with_db(db_pool.clone()))

.and_then(handler::health_handler);

Move the health handler to the handler.rs file and add the database check, like so:

use crate::{db, DBPool};

use warp::{http::StatusCode, reject, Reply, Rejection};

pub async fn health_handler(db_pool: DBPool) -> std::result::Result<impl Reply, Rejection> {

let db = db::get_db_con(&db_pool)

.await

.map_err(|e| reject::custom(e))?;

db.execute("SELECT 1", &[])

.await

.map_err(|e| reject::custom(DBQueryError(e)))?;

Ok(StatusCode::OK)

}

Now, the handler receives a DBPool, which you can use to get a connection and initiate a sanity check query against the database. If an error occurs during the check, use reject::custom to return a custom error. Next, as promised, let’s take a look at error handling with warp.

Clean error handling is one of the most important and often overlooked things in any web application. The goal is to provide helpful errors to API consumers while not leaking internal details. We’ll use the thiserror library to conveniently create custom errors. Start in error.rs and define an Error enum, which has a variant for all of your errors. Here’s the code:

use mobc_postgres::tokio_postgres;

use thiserror::Error;

#[derive(Error, Debug)]

pub enum Error {

#[error("error getting connection from DB pool: {0}")]

DBPoolError(mobc::Error<tokio_postgres::Error>),

#[error("error executing DB query: {0}")]

DBQueryError(#[from] tokio_postgres::Error),

#[error("error creating table: {0}")]

DBInitError(tokio_postgres::Error),

#[error("error reading file: {0}")]

ReadFileError(#[from] std::io::Error),

}

If we could find a way to transform these and other errors into meaningful API responses, we could simply return one of our custom errors from a handler, and the caller would automatically get the correct error message and status code.

To do this, we’ll use warp’s concept of rejections. First, add a convenience type to main.rs for fallible results:

type Result<T> = std::result::Result<T, warp::Rejection>;

Next, make sure your custom errors are recognized as rejections by warp by implementing the Reject trait:

impl warp::reject::Reject for Error {}

Define a rejection handler, which turns rejections into nice error responses in the following form, like so:

#[derive(Serialize)]

struct ErrorResponse {

message: String,

}

Such a rejection handler might look like this:

pub async fn handle_rejection(err: Rejection) -> std::result::Result<impl Reply, Infallible> {

let code;

let message;

if err.is_not_found() {

code = StatusCode::NOT_FOUND;

message = "Not Found";

} else if let Some(_) = err.find::<warp::filters::body::BodyDeserializeError>() {

code = StatusCode::BAD_REQUEST;

message = "Invalid Body";

} else if let Some(e) = err.find::<Error>() {

match e {

Error::DBQueryError(_) => {

code = StatusCode::BAD_REQUEST;

message = "Could not Execute request";

}

_ => {

eprintln!("unhandled application error: {:?}", err);

code = StatusCode::INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR;

message = "Internal Server Error";

}

}

} else if let Some(_) = err.find::<warp::reject::MethodNotAllowed>() {

code = StatusCode::METHOD_NOT_ALLOWED;

message = "Method Not Allowed";

} else {

eprintln!("unhandled error: {:?}", err);

code = StatusCode::INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR;

message = "Internal Server Error";

}

let json = warp::reply::json(&ErrorResponse {

message: message.into(),

});

Ok(warp::reply::with_status(json, code))

}

Basically, we get a Rejection from a handler. Then, depending on the type of error, we set the message and status code for the response. As you can see, we can handle both generic errors, such as not found, and specific problems, such as an error encountered while parsing the JSON body of a request.

The fallback handlers return a generic 500 error to the user and log what went wrong, so you can investigate if necessary without leaking internals. In the routing definition, simply add this error handler using the recover filter:

let routes = health_route

.with(warp::cors().allow_any_origin())

.recover(error::handle_rejection);

Perfect! We’ve made a lot of progress already. All that’s left is to actually implement CRUD handlers for your to-do app.

What is CRUD, you asked? CRUD is a term used to describe a group of operations that are commonly used to manage data in a database. The acronym stands for Create, Read, Update, and Delete, which pretty much sums up what these operations are all about.

When we talk about the CRUD API, we’re referring to a set of endpoints that allow users to carry out these operations on a particular resource or a group of resources. Essentially, it’s a way to define how a user can create new entries, read data that’s already been entered, edit or update existing entries, and delete entries from the database.

Now, we have a web server running and connected to a database as well as a way to handle errors gracefully. The only thing missing from our app is, well, the actual CRUD application logic. We’ll implement the endpoint to create, update, delete, and get todos:

GET /todo/?search={searchString} to list all todos, filtered by an optional search string

POST /todo/ to create a todo

PUT /todo/{id} to update the todo with the given ID

DELETE /todo/{id} to delete the todo with the given ID

todosThe first step is to create todos because without them, we won’t be able to test the other endpoints conveniently. In db.rs, add a function for inserting todos into the database:

const TABLE: &str = "todo";

pub async fn create_todo(db_pool: &DBPool, body: TodoRequest) -> Result<Todo> {

let con = get_db_con(db_pool).await?;

let query = format!("INSERT INTO {} (name) VALUES ($1) RETURNING *", TABLE);

let row = con

.query_one(query.as_str(), &[&body.name])

.await

.map_err(DBQueryError)?;

Ok(row_to_todo(&row))

}

fn row_to_todo(row: &Row) -> Todo {

let id: i32 = row.get(0);

let name: String = row.get(1);

let created_at: DateTime<Utc> = row.get(2);

let checked: bool = row.get(3);

Todo {

id,

name,

created_at,

checked,

}

}

This establishes a connection from the pool, sends an insert query, and transforms the returned row to a Todo. For this to work, you’ll need some data objects, which are defined in data.rs:

use chrono::prelude::*;

use serde_derive::{Deserialize, Serialize};

#[derive(Deserialize)]

pub struct Todo {

pub id: i32,

pub name: String,

pub created_at: DateTime<Utc>,

pub checked: bool,

}

#[derive(Deserialize)]

pub struct TodoRequest {

pub name: String,

}

#[derive(Deserialize)]

pub struct TodoUpdateRequest {

pub name: String,

pub checked: bool,

}

#[derive(Serialize)]

pub struct TodoResponse {

pub id: i32,

pub name: String,

pub checked: bool,

}

impl TodoResponse {

pub fn of(todo: Todo) -> TodoResponse {

TodoResponse {

id: todo.id,

name: todo.name,

checked: todo.checked,

}

}

}

The Todo struct is essentially a mirror of your database table. tokio-postgres can use chrono’s DateTime<Utc> to map to and from timestamps. The other structs are the JSON requests you expect for creating and updating a todo and the response you send back in your list, update, and create handlers. You can now create your actual create handler in handler.rs:

pub async fn create_todo_handler(body: TodoRequest, db_pool: DBPool) -> Result<impl Reply> {

Ok(json(&TodoResponse::of(

db::create_todo(&db_pool, body)

.await

.map_err(|e| reject::custom(e))?,

)))

}

In this case, you get both the request body parsed to a TodoRequest and the db_pool passed into the handler. Once in there, simply call the database function, map it to a TodoResponse, and use warp’s reply::json helper to serialize it to JSON.

If an error happens, handle it with warp’s reject::custom, which enables you to create a rejection out of our custom error type. The only thing missing is the routing definition in main.rs:

let todo = warp::path("todo");

let todo_routes = todo

.and(warp::post())

.and(warp::body::json())

.and(with_db(db_pool.clone()))

.and_then(handler::create_todo_handler));

let routes = health_route

.or(todo_routes)

.with(warp::cors().allow_any_origin())

.recover(error::handle_rejection);

You’ll use warp::path at /todo/ for several routes. Then, using warp’s filters, compose your create handler. Add the post method, specify that you expect a JSON body, and use your with_db filter to signal that you need database access. Finally, finish it up by telling the route which handler to use. All of that is then passed to the routes with an or operator. Test it with the following command:

curl -X POST 'http://localhost:8000/todo/' -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d '{"name": "Some Todo"}'

{"id":1,"name":"Some Todo","checked":false}

Great! Now that you know how it works, you can do the other three handlers all at once. Again, start by adding the database helpers:

const SELECT_FIELDS: &str = "id, name, created_at, checked";

pub async fn fetch_todos(db_pool: &DBPool, search: Option<String>) -> Result<Vec<Todo>> {

let con = get_db_con(db_pool).await?;

let where_clause = match search {

Some(_) => "WHERE name like $1",

None => "",

};

let query = format!(

"SELECT {} FROM {} {} ORDER BY created_at DESC",

SELECT_FIELDS, TABLE, where_clause

);

let q = match search {

Some(v) => con.query(query.as_str(), &[&v]).await,

None => con.query(query.as_str(), &[]).await,

};

let rows = q.map_err(DBQueryError)?;

Ok(rows.iter().map(|r| row_to_todo(&r)).collect())

}

pub async fn update_todo(db_pool: &DBPool, id: i32, body: TodoUpdateRequest) -> Result<Todo> {

let con = get_db_con(db_pool).await?;

let query = format!(

"UPDATE {} SET name = $1, checked = $2 WHERE id = $3 RETURNING *",

TABLE

);

let row = con

.query_one(query.as_str(), &[&body.name, &body.checked, &id])

.await

.map_err(DBQueryError)?;

Ok(row_to_todo(&row))

}

pub async fn delete_todo(db_pool: &DBPool, id: i32) -> Result<u64> {

let con = get_db_con(db_pool).await?;

let query = format!("DELETE FROM {} WHERE id = $1", TABLE);

con.execute(query.as_str(), &[&id])

.await

.map_err(DBQueryError)

}

These are essentially the same as in the create case, except for fetch_todos, where you’d create a different query if there is a search term. Let’s look at the handlers next:

#[derive(Deserialize)]

pub struct SearchQuery {

search: Option<String>,

}

pub async fn list_todos_handler(query: SearchQuery, db_pool: DBPool) -> Result<impl Reply> {

let todos = db::fetch_todos(&db_pool, query.search)

.await

.map_err(|e| reject::custom(e))?;

Ok(json::<Vec<_>>(

&todos.into_iter().map(|t| TodoResponse::of(t)).collect(),

))

}

pub async fn update_todo_handler(

id: i32,

body: TodoUpdateRequest,

db_pool: DBPool,

) -> Result<impl Reply> {

Ok(json(&TodoResponse::of(

db::update_todo(&db_pool, id, body)

.await

.map_err(|e| reject::custom(e))?,

)))

}

pub async fn delete_todo_handler(id: i32, db_pool: DBPool) -> Result<impl Reply> {

db::delete_todo(&db_pool, id)

.await

.map_err(|e| reject::custom(e))?;

Ok(StatusCode::OK)

}

Again, you’ll see some familiar things. Every handler calls the database layer, handles the error, and creates a return value for the caller if everything goes well. The one interesting exception is list_todos_handler, where the aforementioned query parameter is passed in, already parsed to a SearchQuery.

This is how you deal with query parameters in warp. If you had more parameters with different types, you could simply add them to the SearchQuery struct, and they would be automatically parsed. Let’s wire everything up and do one final test, like this:

let todo_routes = todo

.and(warp::get())

.and(warp::query())

.and(with_db(db_pool.clone()))

.and_then(handler::list_todos_handler)

.or(todo

.and(warp::post())

.and(warp::body::json())

.and(with_db(db_pool.clone()))

.and_then(handler::create_todo_handler))

.or(todo

.and(warp::put())

.and(warp::path::param())

.and(warp::body::json())

.and(with_db(db_pool.clone()))

.and_then(handler::update_todo_handler))

.or(todo

.and(warp::delete())

.and(warp::path::param())

.and(with_db(db_pool.clone()))

.and_then(handler::delete_todo_handler));

There are some new things here. To get the query parameter to the list handler, you need to use warp::query(). To get the id parameter for update and delete, use warp::path::param(). Combine the different routes with or operators, and your todo routes are set up.

There are many different ways to create and structure routes in warp. It’s just functions being composed together, so the process is very flexible. For more examples, check out the official docs.

Now, let’s test the whole thing. First, see if the error handling actually works:

curl -v -X POST 'http://localhost:8000/todo/' -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d '{"wrong": "Some Todo"}'

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

{"message":"Invalid Body"}

Next, add another Todo, check it off immediately, and try to update a nonexistent Todo:

curl -X POST 'http://localhost:8000/todo/' -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d '{"name": "Done Todo"}'

{"id":2,"name":"Done Todo","checked":false}

curl -X PUT 'http://localhost:8000/todo/2' -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d '{"name": "Done Todo", "checked": true}'

{"id":2,"name":"Done Todo","checked":true}

curl -X PUT 'http://localhost:8000/todo/2000' -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d '{"name": "Done Todo", "checked": true}'

{"message":"Could not Execute request"}

So far, so good! Now, list them, filter the list, delete one of them, and list them again:

curl -X GET 'http://localhost:8000/todo/' -H 'Content-Type: application/json'

[{"id":1,"name":"Some Todo","checked":false},{"id":2,"name":"Done Todo","checked":true}]

curl -X GET 'http://localhost:8000/todo/?search=Done%20Todo' -H 'Content-Type: application/json'

[{"id":2,"name":"Done Todo","checked":true}]

curl -v -X DELETE 'http://localhost:8000/todo/2' -H 'Content-Type: application/json'

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

curl -X GET 'http://localhost:8000/todo/' -H 'Content-Type: application/json'

[{"id":1,"name":"Some Todo","checked":false}]

Perfect! Everything works as expected. You can find the full code for this example on GitHub.

Building a CRUD app with warp provides a good introduction to Rust web development as warp stands out as one of the top Rust web frameworks. Warp is fast, secure, and has a not-so-steep learning curve if you are familiar with Rust already.

I built the same application with Node.js and Express.js in less time and also plugged both applications into the same database. I also ran a performance test with ab benchmark. Interestingly, the difference in performance wasn’t so much, but of course, the data wasn’t big enough to simulate real-life situations. So, the performance was fair on both sides, and the differences were usually between one to three seconds in favor of Rust.

I hope this tutorial was helpful in helping you kickstart your web development with Rust and warp. For further reading, you should consider taking a look at the documentation to search for specific help when you need it.

Debugging Rust applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are hard to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking the performance of your Rust apps, automatically surfacing errors, and tracking slow network requests and load time, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug your Rust apps — start monitoring for free.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

React Server Components and the Next.js App Router enable streaming and smaller client bundles, but only when used correctly. This article explores six common mistakes that block streaming, bloat hydration, and create stale UI in production.

Gil Fink (SparXis CEO) joins PodRocket to break down today’s most common web rendering patterns: SSR, CSR, static rednering, and islands/resumability.

@container scroll-state: Replace JS scroll listeners nowCSS @container scroll-state lets you build sticky headers, snapping carousels, and scroll indicators without JavaScript. Here’s how to replace scroll listeners with clean, declarative state queries.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

9 Replies to "Create an async CRUD web service in Rust with warp"

I did not know about warp and I really liked. It seems more streamlined than Actix. I will give it a try. Thanks for sharing.

Hello!

Thanks for your article.

To be able to use the API consumed by axios in a recent browser, I had to reconfigure the CORS as follows:

// CORS

let cors = warp::cors()

.allow_methods(&[Method::GET, Method::POST, Method::DELETE])

.allow_headers(vec![header::CONTENT_TYPE, header::AUTHORIZATION])

.allow_any_origin();

The listing of allowed methods & headers is mandatory.

Moreover, I had to put the line .with(cors) after the line .recover(handle_rejection), otherwise, you will have a CORS issue after a rejection is raised.

Hope it helps 🙂

Hey!

Thanks for the feedback and for the heads up about the order of CORS, that definitely makes more sense that way. 🙂

Hello Mario! Nice article, but I just performance tested this code (with my own DB) – it comes down to about 17k req/sec, but Rocket achieves 65k… of course I just stumbled upon warp, but there must be a limiting factor somewhere in the pg connector which I wasn’t able to pinpoint.

Hey Bernd!

That’s interesting for sure. There could be several reasons for this. It could be related to the connection pool, but also Warp-inherent. I’m not aware of any up2date benchmarks comparing the two frameworks.

Also, since this post has been published over a year ago, it still uses Tokio pre 1.x, so using fully upgraded dependencies might improve this as well.

Generally, keep in mind that this example was just a very basic tutorial on how to build a simple DB-backed web-app with Warp. It’s entirely unoptimized, since this simply wasn’t a relevant factor in the tutorial.

Hello there Mario!

Thanks a lot for this awesome guide, this was pretty much exactly what I was looking for 🙂

Even someone like me, who is just dipping his toes into the rust waters, was able to get it up and running while (hopefully) understanding at least some parts of the whole thing 😀

I had some issues though as it seems that since the tutorial was written rust/some dependencies changed a few things around. So I went ahead and updated all dependencies (while adding cargo-husky and itconfig as I simply love those two ^^).

The result can be seen here: https://github.com/ItsNothingPersonal/warp-postgres-example

If there is any problem with me hosting it there, just tell me and I’ll delete it 🙂

Again, thanks for your work!

Hey Sebastian!

That’s great – I’m very happy the article was useful to you and big props on “making it your own”, which is the ultimate goal a tutorial such as this can have – to enable readers to extend and build something on top of it. Great work!

The issues with dependencies are an annoying reality in any not-yet-fully-stable field such as Rust’s async-web, but I’m glad you were able to resolve them. 🙂

Thanks for your feedback. 🙂

Hi Mario, thanks for this tutorial. I’m in the process of learning rust and found this useful, picked up a few tips but must admit some of it I still don’t grasp.

I managed to get it working and even satisfied cargo clippy by ensuring all linting rules were adhered to. There seems to be no reason for many of the closures and just supplying the actual function as the argument was sufficient e.g. .map_err(reject::custom)?; as suggested by clippy.

I’ve had a little dabble with axum and it seems simpler than warp but it’s very early days for me, anyway I’ve got 2 more of your blogs to work through now, Build a Rust + WebAssembly frontend web app with Yew and Full-stack Rust: A complete tutorial with examples. I can’t wait to get stuck in, thanks again.

Is there any git repo of this code As i am facing some issues with whole structure.