async/await in TypeScript

Editor’s note: This article was updated by Chinwike Maduabuchi in January 2026 to include modern async patterns. These updates cover working with data streams using for await...of, handling cancellation with AbortController, and coordinating concurrent tasks with Promise.all.

Asynchronous programming is a way of writing code that can carry out tasks independently of each other, not needing one task to be completed before another gets started. When you think of asynchronous programming, think of multitasking and effective time management.

If you’re reading this, you probably have some familiarity with asynchronous programming in JavaScript, and you may be wondering how it works in TypeScript. That’s what we’ll explore in this guide.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Before diving into async/await, it’s important to mention that promises form the foundation of asynchronous programming in JavaScript/TypeScript. A promise represents a value that might not be immediately available but will be resolved at some point in the future. A promise can be in one of the following three states:

Here’s how to create and work with promises in TypeScript:

// Type-safe Promise creation

interface ApiResponse {

data: string;

timestamp: number;

}

const fetchData = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

try {

// Simulating API call

setTimeout(() => {

resolve({

data: "Success!",

timestamp: Date.now()

});

}, 1000);

} catch (error) {

reject(error);

}

});

Promises can be chained using .then() for successful operations and .catch() for error handling:

fetchData

.then(response => {

console.log(response.data); // TypeScript knows response has ApiResponse type

return response.timestamp;

})

.then(timestamp => {

console.log(new Date(timestamp).toISOString());

})

.catch(error => {

console.error('Error:', error);

});

We’ll revisit the concept of promises later, where we’ll discuss how to possibly execute asynchronous operations in parallel.

async/await in TypeScriptTypeScript is a superset of JavaScript, so async/await behaves the same, with the added benefit of static typing. TypeScript lets you define and enforce the shape of async results, catching type errors at compile time and helping surface bugs earlier in the development process.

At its core, async/await is syntactic sugar over promises. An async function always returns a promise, even if you don’t explicitly annotate the return type. Under the hood, the compiler wraps the returned value in a resolved promise for you.

Here’s an example:

// Snippet 1

const myAsyncFunction = async (url: string): Promise => {

const response = await fetch(url)

return (await response.json()) as T

}

// Snippet 2

const immediatelyResolvedPromise = (url: string): Promise => {

return fetch(url).then(res => res.json() as Promise)

}

Although they look different, the code snippets above are more or less equivalent:

async/await simply enables you to write the code more synchronously and unwraps the promise within the same line of code for you. This is powerful when you’re dealing with complex asynchronous patterns.

To get the most out of the async/await syntax, you’ll need a basic understanding of promises.

As explained earlier, a promise represents the expectation that something will happen in the future, allowing your app to use the result of that future event to trigger other work.

To make this more concrete, let’s walk through a real-world example, translate it into pseudocode, and then look at the actual TypeScript implementation.

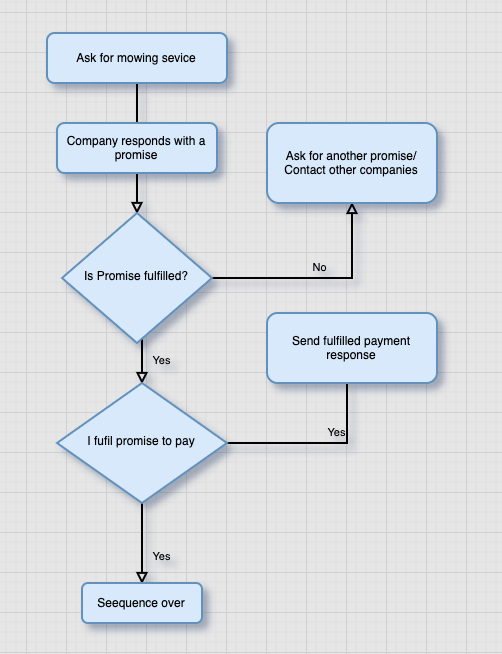

Say I have a lawn to mow. I contacted a mowing company that promises to mow my lawn in a couple of hours. In return, I promise to pay them right after, as long as the lawn is properly mowed.

Do you see the pattern? The key thing to notice is that the second event depends entirely on the first. If the first promise is fulfilled, the next promise runs. If it isn’t, the flow either rejects or stays pending.

Let’s break this sequence down step by step, then explore the code.

Before we write out the full code, it makes sense to examine the syntax for a promise – specifically, an example of a promise that resolves into a string.

We declared a promise with the new + Promise keyword, which takes in the resolve and reject arguments. Now let’s write a promise for the flow chart above:

// I send a request to the company. This is synchronous

// company replies with a promise

const angelMowersPromise = new Promise<string>((resolve, reject) => {

// a resolved promise after certain hours

setTimeout(() => {

resolve('We finished mowing the lawn')

}, 100000) // resolves after 100,000ms

reject("We couldn't mow the lawn")

})

const myPaymentPromise = new Promise<Record<string, number | string>>((resolve, reject) => {

// a resolved promise with an object of 1000 Euro payment

// and a thank you message

setTimeout(() => {

resolve({

amount: 1000,

note: 'Thank You',

})

}, 100000)

// reject with 0 Euro and an unstatisfatory note

reject({

amount: 0,

note: 'Sorry Lawn was not properly Mowed',

})

})

In the code above, we declared both the company’s promises and our promises. The company’s promise is either resolved after 100,000ms or rejected. A Promise is always in one of three states: resolved if there is no error, rejected if an error is encountered, or pending if the Promise has neither rejected nor fulfilled. In our case, it falls within the 100000ms period.

But how can we execute the task sequentially and synchronously? That’s where the then keyword comes in. Without it, the functions simply run in the order they resolve.

thenChaining promises lets you run them in sequence using the then keyword. It reads almost like plain language: do this, then do that, then move on to the next step.

In the example below, angelMowersPromise runs first. If it resolves successfully, myPaymentPromise runs next. If either promise fails, the error is caught in the catch block:

angelMowersPromise

.then(() => myPaymentPromise.then(res => console.log(res)))

.catch(error => console.log(error))

Now let’s look at a more technical example. A common task in frontend programming is to make network requests and respond to the results accordingly.

Below is a request to fetch a list of employees from a remote server:

const api = 'http://dummy.restapiexample.com/api/v1/employees'

fetch(api)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(employees => employees.forEach(employee => console.log(employee.id)) // logs all employee id

.catch(error => console.log(error.message))) // logs any error from the promise

There may be times when you need numerous promises to execute in parallel or sequence. Constructs such as Promise.all or Promise.race are especially helpful in these scenarios.

For example, imagine you need to fetch a list of 1,000 GitHub users and then make an additional request for each user’s avatar using their ID. You don’t want to wait for each request to finish one by one; you just need all the avatars once they’re ready. We’ll take a closer look at this pattern later when we discuss Promise.all.

Now that you have a solid understanding of promises, let’s move on to the async/await syntax.

async/awaitThe async/await syntax simplifies working with promises in JavaScript. It provides an easy interface to read and write promises in a way that makes them appear synchronous.

An async/await will always return a Promise. Even if you omit the Promise keyword, the compiler will wrap the function in an immediately resolved Promise. This enables you to treat the return value of an async function as a Promise, which is useful when you need to resolve numerous asynchronous functions.

As the name implies, async always goes hand in hand with await. That is, you can only await inside an async function. The async function informs the compiler that this is an asynchronous function.

If we convert the promises from above, the syntax looks like this:

const myAsync = async (): Promise<Record<string, number | string>> => {

await angelMowersPromise

const response = await myPaymentPromise

return response

}

As you can immediately see, this looks more readable and appears synchronous. We told the compiler to await the execution of angelMowersPromise before doing anything else. Then, we return the response from myPaymentPromise.

You may have noticed that we omitted error handling. We could do this with the catch block after the then in a promise. But what happens if we encounter an error? That leads us to try/catch.

try/catchWe’ll refer back to the employee-fetching example to see error handling in action, since network requests are especially prone to failure.

For instance, the server might be down, or the request itself could be malformed. In cases like these, we need to catch the error and stop execution gracefully to prevent the application from crashing. The syntax looks like this:

interface Employee {

id: number

employee_name: string

employee_salary: number

employee_age: number

profile_image: string

}

const fetchEmployees = async (): Promise<Array<Employee> | string> => {

const api = 'http://dummy.restapiexample.com/api/v1/employees'

try {

const response = await fetch(api)

const { data } = await response.json()

return data

} catch (error) {

if (error) {

return error.message

}

}

}

We defined the function as async, and we expect it to return either an array of employees or a string containing an error message. As a result, the function’s return type is Promise<Array<Employee> | string>.

The code inside the try block runs when everything goes as expected. If an error occurs, execution jumps to the catch block, where we return the message property from the error object.

This approach ensures that the first error thrown inside the try block is immediately caught and handled. Leaving errors uncaught can lead to hard-to-debug behavior or even cause the entire application to fail.

While traditional try/catch blocks are effective for catching errors at the local level, they can become repetitive and clutter the main business logic when used too frequently. This is where higher-order functions come into play.

A higher-order function is a function that takes one or more functions as arguments or returns a function. In the context of error handling, a higher-order function can wrap an asynchronous function and handle any errors it might throw, thereby abstracting the try/catch logic away from the core business logic.

The main idea behind using higher-order functions for error handling in async/await is to create a wrapper function that takes an async function as an argument along with any parameters that the async function might need. Inside this wrapper, we implement a try/catch block. This approach allows us to handle errors in a centralized manner, making the code cleaner and more maintainable.

Let’s refer to the employee fetching example:

// Async function to fetch employee data

async function fetchEmployees(apiUrl: string): Promise<Employee[]> {

const response = await fetch(apiUrl);

const data = await response.json();

return data;

}

// Wrapped version of fetchEmployees using the higher-order function

const safeFetchEmployees = (url: string) => handleAsyncErrors(fetchEmployees, url);

// Example API URL

const api = 'http://dummy.restapiexample.com/api/v1/employees';

// Using the wrapped function to fetch employees

safeFetchEmployees(api)

.then(data => {

if (data) {

console.log("Fetched employee data:", data);

} else {

console.log("Failed to fetch employee data.");

}

})

.catch(err => {

// This catch block might be redundant, depending on your error handling strategy within the higher-order function

console.error("Error in safeFetchEmployees:", err);

});

In this example, the safeFetchEmployees function uses the handleAsyncErrors higher-order function to wrap the original fetchEmployees function.

This setup automatically handles any errors that might occur during the API call, logging them and returning null to indicate an error state. The consumer of safeFetchEmployees can then check if the returned value is null to determine if the operation was successful or if an error occurred.

Promise.allAs mentioned earlier, there are times when we need promises to execute in parallel.

Let’s look at an example from our employee API. Say we first need to fetch all employees, then fetch their names, and then generate an email from the names. Obviously, we’ll need to execute the functions in a synchronous manner and also in parallel so that one doesn’t block the other.

In this case, we would make use of Promise.all. According to Mozilla, “Promise.all is typically used after having started multiple asynchronous tasks to run concurrently and having created promises for their results so that one can wait for all the tasks to be finished.”

In pseudocode, we’d have something like this:

/employeeid from each user. Fetch each user => /employee/{id}const baseApi = 'https://reqres.in/api/users?page=1'

const userApi = 'https://reqres.in/api/user'const fetchAllEmployees = async (url: string): Promise<Employee[]> => {

const response = await fetch(url)

const { data } = await response.json()

return data

}const fetchEmployee = async (url: string, id: number): Promise<Record<string, string>> => {

const response = await fetch(${url}/${id}) const { data } = await response.json() return data } const generateEmail = (name: string): string => { return ${name.split(' ').join('.')}@company.com }const runAsyncFunctions = async () => { try { const employees = await fetchAllEmployees(baseApi) Promise.all( employees.map(async user => { const userName = await fetchEmployee(userApi, user.id) const emails = generateEmail(userName.name) return emails }) ) } catch (error) { console.log(error) } } runAsyncFunctions()

In the above code, fetchEmployees fetches all the employees from the baseApi. We await the response, convert it to JSON, and then return the converted data.

The most important concept to keep in mind is how we sequentially executed the code line by line inside the async function with the await keyword. We’d get an error if we tried to convert data to JSON that has not been fully awaited. The same concept applies to fetchEmployee, except that we’d only fetch a single employee. The more interesting part is the runAsyncFunctions, where we run all the async functions concurrently.

First, wrap all the methods within runAsyncFunctions inside a try/catch block. Next, await the result of fetching all the employees. We need the id of each employee to fetch their respective data, but what we ultimately need is information about the employees.

This is where we can call upon Promise.all to handle all the Promises concurrently. Each fetchEmployee Promise is executed concurrently for all the employees. The awaited data from the employees’ information is then used to generate an email for each employee with the generateEmail function.

In the case of an error, it propagates as usual, from the failed promise to Promise.all, and then becomes an exception we can catch inside the catch block.

Promise.allSettledPromise.all is great when we need all promises to succeed, but real-world applications often need to handle situations where some operations might fail while others succeed. Let’s consider our employee management system: What if we need to update multiple employee records, but some updates might fail due to validation errors or network issues?

This is where Promise.allSettled comes in handy. Unlike Promise.all, which fails completely if any promise fails, Promise.allSettled will wait for all promises to complete, regardless of whether they succeed or fail. It gives us information about both successful and failed operations.

Let’s enhance our employee management system to handle bulk updates:

interface UpdateResult {

id: number;

success: boolean;

message: string;

}

const updateEmployee = async (employee: Employee): Promise<UpdateResult> => {

const api = `${userApi}/${employee.id}`;

try {

const response = await fetch(api, {

method: 'PUT',

body: JSON.stringify(employee),

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json'

}

});

const data = await response.json();

return {

id: employee.id,

success: true,

message: 'Update successful'

};

} catch (error) {

return {

id: employee.id,

success: false,

message: error instanceof Error ? error.message : 'Update failed'

};

}

};

const bulkUpdateEmployees = async (employees: Employee[]) => {

const updatePromises = employees.map(emp => updateEmployee(emp));

const results = await Promise.allSettled(updatePromises);

// Process results and generate a report

const summary = results.reduce((acc, result, index) => {

if (result.status === 'fulfilled') {

acc.successful.push(result.value);

} else {

acc.failed.push({

id: employees[index].id,

error: result.reason

});

}

return acc;

}, {

successful: [] as UpdateResult[],

failed: [] as Array<{id: number; error: any}>

});

return summary;

};

Think of Promise.allSettled like a project manager tracking multiple tasks. Instead of stopping everything when one task fails (like Promise.all would), the manager continues monitoring all tasks and provides a complete report of what succeeded and what failed. This is particularly useful when you need to:

for await...ofSometimes we need to process large amounts of data that come in chunks or pages. Imagine you’re exporting employee data from a large enterprise system – there might be thousands of records that come in batches to prevent memory overload.

The for await...of loop is perfect for this scenario and has become increasingly prevalent in modern AI development frameworks. Whether you’re streaming generated text from language models like OpenAI’s GPT, Claude, or Gemini, this pattern comes in handy.

It allows us to process asynchronous data streams one chunk at a time, making our code both efficient and readable. Here’s a practical example of streaming AI-generated text using the Vercel AI SDK:

import { streamText } from 'ai'

async function generateStory() {

const result = streamText({

model: yourModel,

prompt: 'Write a short story about a developer learning TypeScript',

})

// Stream the text as it's being generated

for await (const chunk of result.textStream) {

process.stdout.write(chunk)

}

}

As the AI model generates each piece of text, it immediately becomes available to your application. You don’t have to wait for the entire response to be generated before showing something to the user.

You can also use for await...of with any async iterable, including paginated API responses:

async function fetchAllUsers() {

const users: User[] = []

let page = 1

// Create an async generator for pagination

async function* userPages() {

while (true) {

const response = await fetch(`/api/users?page=${page}`)

const data = await response.json()

if (data.users.length === 0) break

yield data.users

page++

}

}

// Process each page as it arrives

for await (const pageUsers of userPages()) {

users.push(...pageUsers)

console.log(`Loaded ${users.length} users so far...`)

}

return users

}

Think of for await...of like a conveyor belt in a factory. Instead of waiting for all products (data) to be manufactured before starting to pack them (process them), we can pack each product as it comes off the belt. This approach has several benefits:

AbortControllerIn modern web development, especially when dealing with expensive operations like AI model calls, long-running data processing, or network requests, you often need the ability to cancel operations that are no longer needed. This is where the AbortController and AbortSignal APIs come into play to provide an elegant approach to cancellation.

AbortController provides a way to abort one or more async operations mid-execution. This is particularly useful for:

AbortSignal with timeoutsHere’s a simple example showing how to use AbortController to automatically timeout a request:

async function fetchWithTimeout(url: string, timeoutMs: number = 5000) {

const controller = new AbortController()

// Set up timeout

const timeoutId = setTimeout(() => controller.abort(), timeoutMs)

try {

const response = await fetch(url, {

signal: controller.signal,

})

return await response.json()

} catch (error) {

if (error instanceof Error && error.name === 'AbortError') {

throw new Error(`Request timed out after ${timeoutMs}ms`)

}

throw error

} finally {

clearTimeout(timeoutId)

}

}

// Usage

try {

const data = await fetchWithTimeout('https://api.example.com/data', 3000)

console.log(data)

} catch (error) {

console.error('Failed to fetch:', error.message)

}

You can also manually abort operations when they’re no longer needed, such as when a user clicks a cancel button during a file upload. Here’s an example in React.js:

import { useState, useRef } from 'react'

function ImageUploader() {

const [uploading, setUploading] = useState(false)

const abortControllerRef = useRef<AbortController | null>(null)

const uploadImage = async (file: File) => {

const controller = new AbortController()

abortControllerRef.current = controller

setUploading(true)

try {

const formData = new FormData()

formData.append('image', file)

const response = await fetch('/api/upload', {

method: 'POST',

body: formData,

signal: controller.signal,

})

const result = await response.json()

console.log('Upload complete:', result)

setUploading(false)

} catch (error) {

if (error instanceof Error && error.name === 'AbortError') {

console.log('Upload cancelled by user')

} else {

console.error('Upload failed:', error)

}

setUploading(false)

}

}

const cancelUpload = () => {

abortControllerRef.current?.abort()

}

return (

<div>

<input

type='file'

onChange={(e) => e.target.files?.[0] && uploadImage(e.target.files[0])}

disabled={uploading}

/>

{uploading && <button onClick={cancelUpload}>Cancel Upload</button>}

</div>

)

}

Now that we’ve explored AbortController, let’s see how it enables structured concurrency patterns. While JavaScript doesn’t have built-in structured concurrency like some other languages, the concepts are worth understanding as they influence how we should think about async operations. Structured concurrency is about organizing concurrent operations in a way that:

We can implement structured concurrency patterns in TypeScript using AbortController and proper promise management with a functional approach.

First, let’s define our types and the core task runner structure. A TaskRunner will hold the AbortController instance and keep track of all running tasks:

// Task is a function that accepts an AbortSignal and returns a Promise

type Task<T> = (signal: AbortSignal) => Promise<T>

interface TaskRunner {

controller: AbortController

runningTasks: Set<Promise<any>>

}

// Function to create a new task runner

const createTaskRunner = (): TaskRunner => ({

controller: new AbortController(),

runningTasks: new Set(),

})

Next, we need a way to run tasks. The runTask function below wraps the execution, ensuring the task receives the signal and is tracked in the runningTasks set:

const runTask = <T>(runner: TaskRunner, task: Task<T>): Promise<T> => {

// Pass the controller's signal to the task

const taskPromise = task(runner.controller.signal)

// Track the running task

runner.runningTasks.add(taskPromise)

// Remove the task from tracking when it completes (success or failure)

return taskPromise.finally(() => {

runner.runningTasks.delete(taskPromise)

})

}

Now we can create a runTaskGroup function to execute multiple tasks concurrently. If one task fails, we want to cancel the rest:

>const runTaskGroup = async <T>(

runner: TaskRunner,

tasks: Array<Task<T>>

): Promise<T[]> => {

const taskPromises = tasks.map((task) => runTask(runner, task))

try {

// Wait for all tasks to complete

return await Promise.all(taskPromises)

} catch (error) {

// If any task fails, trigger the abort controller to cancel all others

runner.controller.abort()

throw error

}

}

This implementation highlights a crucial benefit of structured concurrency. Standard Promise.all fails fast by rejecting as soon as one promise fails. However, it keeps running the other promises in the background, wasting resources on operations whose results will be ignored.

By combining Promise.all with AbortController in our catch block, we upgrade fail-fast to “fail-fast and cancel”. As soon as one task errors out, we immediately signal all other sibling tasks to stop, saving network bandwidth and processing power.

Finally, we need a cleanup mechanism. The shutdown function aborts any remaining tasks and waits for them to settle:

const shutdown = async (runner: TaskRunner): Promise<void> => {

runner.controller.abort()

// Wait for all tasks to finish (either complete or reject)

await Promise.allSettled(Array.from(runner.runningTasks))

console.log('All tasks completed or cancelled')

}

Here’s how we can put it all together in the employee workflow:

const processEmployeeWorkflow = async () => {

const taskRunner = createTaskRunner()

try {

// Run these three tasks concurrently

const results = await runTaskGroup(taskRunner, [

async (signal) => {

const response = await fetch('/api/employees', { signal })

return response.json()

},

async (signal) => {

const response = await fetch('/api/analytics', {

method: 'POST',

signal,

})

return response.json()

},

async (signal) => {

const response = await fetch('/api/reports', { signal })

return response.json()

},

])

console.log('All workflow tasks completed successfully')

return results

} catch (error) {

console.error('Workflow failed:', error)

throw error

} finally {

// Ensure you clean up resources

await shutdown(taskRunner)

}

}

This functional pattern improves upon standard promise management in three key ways:

async/await in higher-order functionsCombining higher-order functions with async/await creates powerful patterns for handling asynchronous operations.

When working with our employee management system, we often need to process arrays of data asynchronously. Let’s see how we can effectively use array methods with async/await:

// Async filter: Keep only active employees

async function filterActiveEmployees(employees: Employee[]) {

const checkResults = await Promise.all(

employees.map(async (employee) => {

const status = await checkEmployeeStatus(employee.id);

return { employee, isActive: status === 'active' };

})

);

return checkResults

.filter(result => result.isActive)

.map(result => result.employee);

}

// Async reduce: Calculate total department salary

async function calculateDepartmentSalary(employeeIds: number[]) {

return await employeeIds.reduce(async (promisedTotal, id) => {

const total = await promisedTotal;

const employee = await fetchEmployeeDetails(id);

return total + employee.salary;

}, Promise.resolve(0)); // Initial value must be a Promise

}

When working with these array methods, there are some important considerations:

map with async operations returns an array of promises that usually needs to be handled with Promise.allfilter needs special handling because you can’t directly use a promise result as a filter conditionreduce with async operations requires careful promise handling for the accumulatorThere are use cases where utility functions are needed to carry out some operations on responses returned from asynchronous calls. We can create reusable higher-order functions that wrap async operations with these additional functionalities:

// Higher-order function for caching async results

function withCache<T>(

asyncFn: (id: number) => Promise<T>,

ttlMs: number = 5000

) {

const cache = new Map<number, { data: T; timestamp: number }>();

return async (id: number): Promise<T> => {

const cached = cache.get(id);

const now = Date.now();

if (cached && now - cached.timestamp < ttlMs) {

return cached.data;

}

const data = await asyncFn(id);

cache.set(id, { data, timestamp: now });

return data;

};

}

// Usage example

const cachedFetchEmployee = withCache(async (id: number) => {

const response = await fetch(`${baseApi}/employee/${id}`);

return response.json();

});

In the above snippet, the withCache higher-order function adds caching capability to any async function that fetches data by ID. If the same ID is requested multiple times within five seconds (the default TTL), the function returns the cached result instead of making another API call. This significantly reduces unnecessary network requests when the same employee data is needed multiple times in quick succession.

Awaited typeAwaited is a utility type that models operations like await in async functions. It unwraps the resolved value of a promise, discarding the promise itself, and works recursively, thereby removing any nested promise layers.

Awaited is the type of value that you expect to get after awaiting a promise. It helps your code understand that once you use await, you’re not dealing with a promise anymore, but with the actual data you wanted.

Here’s the basic syntax:

type MyPromise = Promise<string>; type AwaitedType = Awaited<MyPromise>; // AwaitedType will be 'string'

The Awaited type does not exactly model the then method in promises. Awaited can be relevant when using then in async functions. If you use await inside a then callback, Awaited helps infer the type of the awaited value, avoiding the need for additional type annotations.

Awaited can help clarify the type of data and awaitedValue in async functions, even when using then for promise chaining. However, it doesn’t replace the functionality of then itself.

Mastering async/await in TypeScript is key to building modern, responsive applications. We covered the fundamentals of promises, error handling with try/catch, and advanced patterns like concurrent execution with Promise.all. We also explored efficient data streaming with for await...of and ways to manage cancellation and timeouts using AbortController. When combined with TypeScript’s type safety, these tools help you write asynchronous code that’s reliable, efficient, and easier to maintain and debug.

For further reading and deep dives into these topics, check out these resources:

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks, and with plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you understand your web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

React Server Components and the Next.js App Router enable streaming and smaller client bundles, but only when used correctly. This article explores six common mistakes that block streaming, bloat hydration, and create stale UI in production.

Gil Fink (SparXis CEO) joins PodRocket to break down today’s most common web rendering patterns: SSR, CSR, static rednering, and islands/resumability.

@container scroll-state: Replace JS scroll listeners nowCSS @container scroll-state lets you build sticky headers, snapping carousels, and scroll indicators without JavaScript. Here’s how to replace scroll listeners with clean, declarative state queries.

Explore 10 Web APIs that replace common JavaScript libraries and reduce npm dependencies, bundle size, and performance overhead.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

2 Replies to "A guide to <code>async/await</code> in TypeScript"

Logrocket does not catch uncaught promise rejections (at least in our case).

It can catch uncaught promise rejections—it just doesn’t catch them automatically. You can manually set it up to do so!